Summary

In a courtroom, I now have to worry about not getting myself detained rather than speaking the truth. This is especially true when I have to represent political cases. Everyone at the court knows who I am, and the court has all my credentials and personal information. The SAC [military junta] can detain me at any time, and they can and will make up any reasons they want.

—Yangon-based lawyer, October 11, 2022

Since the February 1, 2021 military coup in Myanmar, the State Administration Council (SAC) junta has arbitrarily detained thousands of anti-coup activists and critics in mass arrests and prosecuted them in summary trials that fall far short of international standards. Among those wrongfully convicted are protesters, journalists, human rights defenders, and politicians from the ousted National League for Democracy (NLD) party.

The severe deprivation of liberty is among the grave crimes committed by the junta, as well as murder, torture, enforced disappearance, and other inhumane acts causing great suffering. These have been committed as part of a widespread and systematic attack on the population, amounting to crimes against humanity.

In the face of these abuses, dozens of lawyers in Myanmar have attempted to represent those arrested and provide them a legal defense. At every turn they have faced systematic obstacles imposed by military authorities and restrictions impeding their work. Making matters worse, they themselves have faced threats, arbitrary arrest, detention, and prosecution, and in some instances, torture and other ill-treatment.

Most notably, the junta has created “special courts”—closed courts inside prisons to fast-track politically sensitive cases. As a result, many cases that would have been heard before regular criminal courts before the coup, are now under the jurisdiction of these junta-controlled special courts.

Inside special courts, authorities have imposed numerous severe restrictions on lawyers including prohibitions on private communications with clients before hearings. Lawyers said that junta officials frequently obstructed or prevented them from carrying out their professional duties, denying suspects their rights to due process and a fair trial.

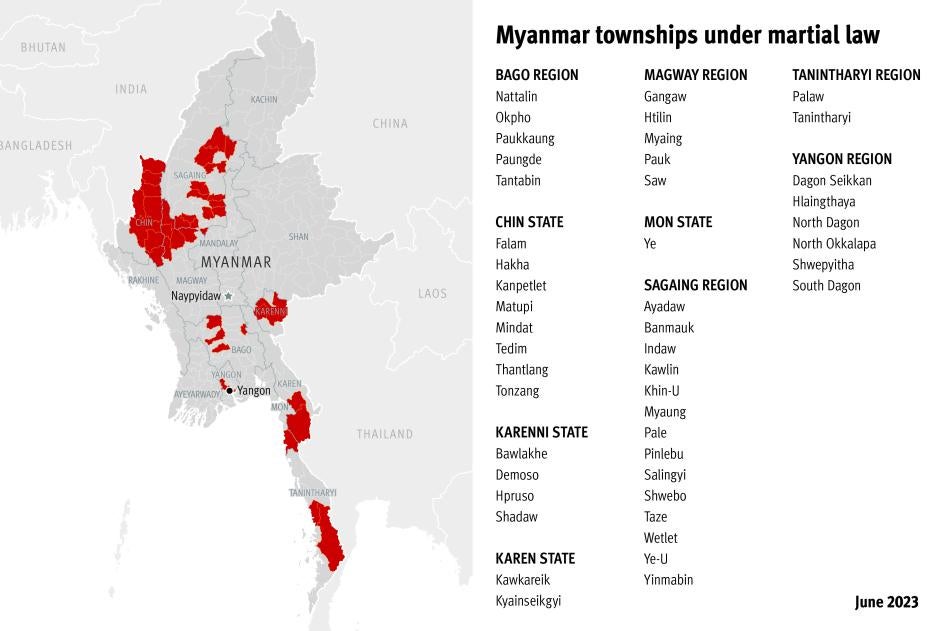

In the 47 townships in which the junta has imposed martial law, the junta has also convened military tribunals to adjudicate criminal cases involving civilian defendants. The military tribunals also typically operate in prisons. Suspects may not have access to a lawyer, and trials are summary and invariably result in convictions and often heavy sentences.

Lawyers told Human Rights Watch that the trials in the special courts are disorganized and chaotic, with often only a few lawyers representing hundreds of defendants. Junta authorities have threatened and harassed lawyers so successfully that few have been willing to put themselves at risk of further surveillance and intimidation and many have stopped taking cases.

The junta’s revisions to numerous laws since the coup have added to the systematic obstacles for lawyers, forcing them to attempt to represent their clients charged under the new criminal offenses and in proceedings that are closed to the public. These changes to the law have further eroded the already minimal human rights protections existing in Myanmar. Most detainees facing trials in connection with protests have been charged under the amended section 505A of the Penal Code, which criminalizes comments or actions that call into question the legitimacy of the coup or the junta administration and is punishable by up to three years in prison.

The junta has also increasingly targeted criminal defense lawyers for arrest. Some have been subjected to ill-treatment and torture by junta security forces in detention. The authorities have arrested lawyers as they leave the special courts inside prisons after defending their clients. In Mandalay in April 2022, for instance, police detained senior attorney Ywet Nu Aung as she left a hearing inside Oh-Bo prison, where she was representing the deposed Mandalay NLD Chief Minister Zaw Myint Maung.

In December 2022, a special court sentenced Ywet Nu Aung to 15 years in prison with hard labor under a junta-amended section of the Counter-Terrorism Law. She was accused of helping to provide financial support to anti-junta militias. Her colleagues believe that the fabricated charges were aimed at curbing her defense of senior NLD government officials.

The Assistance Association for Political Prisoners reported that as of April 2023, at least 32 lawyers remain detained in pretrial detention or are serving sentences under a range of laws including section 505A of the Penal Code, which prohibits criticism of the junta, amended provisions of the Counter-Terrorism Law, Unlawful Associations Act, and the colonial-era Explosive Substance Act. The actual number of lawyers who have been detained since the coup is likely much higher, but as this report shows, the ad hoc way charges are filed makes it difficult to ascertain the numbers of those in custody.

One lawyer who spoke to Human Rights Watch shortly after her release from prison said police blindfolded her, placed her in stress positions, and deprived her of food and water during interrogation.

Several sources familiar with the situation of Tin Win Aung, a high court lawyer from Mandalay Region, said he suffered a broken arm and leg, and had to have a feeding tube inserted into his stomach from the injuries he sustained during beatings by security force personnel during pretrial detention. One lawyer with knowledge of his case said: “Our colleagues in Mandalay were tortured. Tin Win Aung was beaten very badly, and they repeatedly rolled a heavy wooden stick over his shins and legs. We got all the news from other inmates. Everyone thought he was on the brink of death.”

Human Rights Watch found an emerging pattern of intimidation and harassment against defense lawyers representing political detainees such as former members of parliament, deposed government officials, and anti-junta activists. The 19 defense lawyers to whom Human Rights Watch spoke, all said they had experienced intimidation and surveillance by junta authorities. In some cases, the junta authorities appear to have targeted lawyers in reprisal for their representation of activists charged with sedition, incitement, or terrorism.

Many of the detained lawyers also face charges under section 505A but can face multiple charges under various amended junta legislation. The junta has at times shut down mobile internet data and restricted movement by extending states of emergency and expanding areas under martial law.

Lawyers describe a criminal justice system that is in a state of chaos, where the number of lawyers willing or able to work under junta conditions is dwindling.

By interfering with the ability of lawyers to access their clients and present a legal defense, as well as arresting and prosecuting them for doing the job, Myanmar’s junta is violating the human rights of lawyers and thousands of defendants who have the right to legal counsel. As the UN Human Rights Committee stated in 2007, commenting on the right to equality before courts and to a fair trial, “The availability or absence of legal assistance often determines whether or not a person can access the relevant proceedings or participate in them in a meaningful way.”

Along with the adoption of criminal laws and procedures that do not meet international due process standards and the elimination of an independent judiciary, the junta’s attack on lawyers has deprived everyone in Myanmar the right to a fair trial and equal protection under the law.

Foreign governments and regional organizations concerned about the disastrous human rights situation in Myanmar should adopt a range of measures against the military junta, including targeted sanctions against junta members implicated in abuses and against military-linked companies. They should support United Nations Security Council resolutions imposing an embargo on weapons and lethal assistance to Myanmar and referring the situation in Myanmar to the International Criminal Court. In pressing for the release of political prisoners, all governments should raise the harassment and jailing of lawyers, and seek to improve their ability to defend those imprisoned, often for years, for peacefully protesting the junta’s abuses.

Recommendations

To the Myanmar military junta:

- Urgently restore civilian democratic rule.

- Dismantle the “special courts” and military tribunals; all civilians charged with a legally recognizable offense should be prosecuted in regular civilian courts meeting international due process standards.

- End all harassment of, attacks on, and interference with lawyers, particularly those handling cases involving politically motivated prosecutions.

- Drop all charges or exonerate and release from detention anyone held for the peaceful exercise of their human rights.

- Adopt all necessary measures to end torture and other ill-treatment in custody.

- Cease to enforce existing legislation that violates fundamental human rights.

- Revoke post-coup amendments to legislation and policies that violate fundamental human rights.

- End all use of the death penalty.

- Ensure lawyers can fulfill their duties under international law, including by respecting the United Nations Basic Principles on the Role of Lawyers

A future civilian democratic government in Myanmar should commit to:

- Fundamentally revise, in consultation with legal professionals and relevant civil society organizations, the justice system in Myanmar so that it meets international human rights standards, including the right to a fair trial.

- Revise Myanmar’s criminal laws to conform to international human rights standards for freedom of expression, association, and peaceful assembly.

- Develop national institutions, including an independent judiciary and human rights mechanisms, to strengthen the rule of law in Myanmar in accordance with international human rights standards.

- Ratify core international human rights treaties, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, and the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination.

To United Nations member states and international organizations, including the European Union, and Association of Southeast Asian Nations

- Call for all criminal charges to be dropped, and the exoneration of people convicted for exercising their fundamental rights and seek their immediate release.

- Publicly denounce all misuse of the criminal justice system, including denial of the right to a fair trial, mistreatment and attacks on lawyers, and the use of the death penalty.

- Impose coordinated, targeted sanctions against senior military and junta officials responsible for serious human rights violations.

- Impose coordinated, targeted sanctions against Myanmar military-owned conglomerates and subsidiaries that benefit the military.

- Press UN Security Council members to impose a comprehensive arms embargo and referral of the country situation to the International Criminal Court.

- Support local groups monitoring human rights and documenting cases for future justice initiatives, and support an assistance network for lawyers in Myanmar.

To the UN Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers

- Investigate abuses in Myanmar’s special courts and military tribunals.

- Raise concerns privately and publicly about ongoing attacks on legal professionals.

To Foreign Bar Associations and Lawyers’ Associations

- Publicly raise concerns about the Myanmar junta’s interference in the work of legal professionals in Myanmar, including harassment, retaliation, arbitrary arrests and detention, and assaults on lawyers.

Methodology

The report is based on remote interviews with 19 lawyers and 7 legal advisers to international nongovernmental organizations working inside the Myanmar military junta’s special courts system. Although Human Rights Watch was unable to obtain full documentation of the cases included in this report because the junta authorities have not made such information available, interviews with other nongovernmental sources, media outlets, and individuals familiar with the cases corroborate our findings.

In some cases, the names of lawyers and other sources interviewed are withheld or given pseudonyms to protect their identities. Human Rights Watch has not disclosed the locations of lawyers working inside the special court system without the lawyer’s express permission.

None of the lists of detained lawyers made available to Human Rights Watch were comprehensive, suggesting that some arrests and subsequent charges or convictions are not officially registered.

Legal Standards Under Attack

We are heavily surveilled; we’re told [by the judges] that we can’t ask witnesses certain questions; we receive threats from prison officials, intelligence units, and random people. They take down our names, take photos of us, come to our houses, and watch from outside. The lawyers who are going into the special courts inside the prisons are harassed the most. They have all our details so there is a constant threat hanging over us.

—Lawyer, Yangon, October 25, 2022

On February 1, 2021, the Myanmar military staged a coup and replaced the recently elected civilian government with a military junta. In the face of widespread opposition, the junta responded with a campaign of brutal suppression. Since then, the police and military have arbitrarily detained more than 21,000 people and killed at least 3,200, according to the nongovernmental organization Assistance Association for Political Prisoners.[1] The numerous abuses, committed as part of a widespread and systematic attack on the population, amount to crimes against humanity.

Myanmar’s junta, the State Administration Council (SAC), revised the country’s legal system to make protests a criminal offense, facilitate arbitrary arrests, and detain anti-coup demonstrators. The junta increasingly relied on intimidation and excessive force to quell peaceful protests, while attempting to give a veneer of legality to its actions by amending laws and removing existing protections in the legal system.

Commander-in-Chief Sr. Gen. Min Aung Hlaing appointed himself as chair of the SAC and oversaw various legislative changes, [2] all adopted outside the parliamentary process.[3]

Over time the junta expanded its arbitrary arrests, carrying out night raids and targeting anyone deemed a threat—including the lawyers attempting to represent the thousands of people the security forces had detained.

State intimidation of the legal profession has a long history in Myanmar. During the military coup in 1962 under Gen. Ne Win, the military detained the Supreme Court’s chief justice and quickly dismantled the country’s courts. For five decades, the military instrumentalized the courts, subordinating and rendering them loyal to the military.[4] Judges and lawyers opposed to the military were removed from the administration and replaced instead with military officials unfamiliar with the law.[5]

During Ne Win’s government, lawyers considered to be unsupportive of the regime were disbarred or prosecuted. For example, human rights lawyer Thein Than Oo served three separate prison sentences under military rule, and once served 10 years in solitary confinement for a 14-year prison sentence.[6] The military courts disbarred Thein Than Oo upon his release in 2001. The military government at the time often used this tactic to deter lawyers from representing dissidents or engaging in dissent themselves, with hundreds of lawyers estimated as having been disbarred in Myanmar over a 25-year period.[7]

This practice continued through the nominally civilian government of retired general Thein Sein from 2011 to 2016. At least 32 lawyers were disbarred in 2011. The nongovernmental Asian Human Rights Commission reported that they were disbarred “not in response to breaches of professional codes of conduct but because of dissatisfaction of the authorities with their political activities, or efforts to defend the rights of persons accused in political cases.”[8]

After its landslide election win in 2015, the National League for Democracy (NLD) began to introduce some reforms to better regulate the work of lawyers and reinstate previously disbarred lawyers and judges. However, the NLD was very slow to implement key legal reforms, including repealing a range of repressive laws used to arrest, prosecute, and imprison individuals for exercising their rights to freedom of expression, association, and peaceful assembly.[9]

In 2016, lawyers formed the national Independent Lawyers’ Association of Myanmar (ILAM). The International Bar Association Human Rights Initiative (IBAHRI) and other nongovernmental organizations helped introduce programs to expand legal capacity and knowledge of the law.[10]

After the 2021 coup, the junta quickly implemented legal changes that eroded human rights protections. The Code of Criminal Procedure Amendment Law was amended to include several new and revised offenses there were non-bailable and subject to warrantless arrest.[11]

On February 14, 2021, the junta announced amendments to the Penal Code to criminalize the acts of demonstrators and anyone publicly criticizing the military coup through any means.

Under the colonial-era section 141 of the Penal Code, many peaceful protesters have been charged with “unlawful assembly.”[12] Penal Code section 505(b) permits prosecutions for statements “likely to cause fear or alarm to the public, or to any section of the public, whereby any person may be induced to commit an offence against the State or against the public tranquility,” which carries a penalty of up to two years in prison.[13]

The junta added a new provision, section 505A, that could be used to punish comments critical of the coup or the military junta, among others. The new section criminalizes comments that “cause fear,” spread “false news, [or] agitates directly or indirectly a criminal offense against a Government employee.” Violation of the section is punishable by up to three years in prison.[14] The broader language appears designed to make it easier to arrest any opposition to the coup. About half the lawyers detained were charged with this offense. As of April 2023, the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners has documented that the junta has sentenced just 6 of the 32 lawyers still detained. Four are serving sentences under charges of section 505A.

The junta also significantly broadened the “treason” provisions in the Penal Code. Section 124A, which already criminalized comments that “bring into hatred or contempt” or “excite disaffection against” the government, was expanded to include comments relating to the military services generally and military personnel, effectively making it a criminal offense

to criticize the military or military personnel. Violation of the section is punishable by up to 20 years in prison.[15]

The newly added section 124C imposes a prison term of up to 20 years for anyone who intends to “sabotage or hinder the performance of the Defense Services and law enforcement organizations who are engaged in preserving the stability of the state.” This provision would criminalize efforts to encourage security forces to join the Civil Disobedience Movement or permit unauthorized protests.

After the military declared a state of emergency on February 1, 2021, it imposed martial law in parts of Yangon, Sagaing and Mandalay Regions, and Chin State.[16] On February 1, 2023, the junta extended the state of emergency across the country for another six months. On February 2, the junta imposed new martial law orders in 37 additional townships in Chin, Karen, Karenni, Magway and Mon States, and Bago, Sagaing, and Tanintharyi Regions, bringing up to 47 townships under martial law.[17]

Under martial law, legal proceedings held in military tribunals against alleged coup opponents deny defendants any semblance of a fair trial. Defendants are prohibited a legal defense and the proceedings are entirely opaque. In essence, martial law orders all but guarantee that ongoing military abuses remain unchecked and those responsible unaccountable.[18]

In May 2021, the junta reversed previous amendments by the NLD government to the 2016 Legal Aid Act, removing legal aid service provisions for those in pretrial detention and denying access to legal aid for those detained on criminal charges.[19] Changes to the legal aid provision also affect defense lawyers who continue to provide legal advice to the families of individuals charged under section 505A of the Penal Code or other criminal offenses. If lawyers provide pro-bono services, they also risk police charging them under 505A for appearing to be a supporter of the client.

On October 18, 2021, the junta amended the Bar Council Act, preventing ILAM members from voting in their elected representatives to the bar council, and instead approving only junta-nominated appointees.[20] The restrictions further tighten controls over lawyers to be able to renew their licenses and openly advocate for human rights.

Another risk for lawyers representing clients facing politically motivated charges is the new Organization Registration Law, adopted on October 29, 2022. This law prohibits direct and indirect contact with organizations or persons accused of having committed “terror” acts, or “unlawful” organizations or their members, and carries a five-year prison term and a fine of over 5 million kyat (US$2,300).[21]

The junta-amended Myanmar Police Force Law, enacted in March 2022, formally brought the police under junta control, requiring police officers to comply with all military orders, including taking part in military operations.[22]

These laws—among others—seek to deter any political opposition and undermine the lawyers committed to protecting the rights of those caught up in Myanmar’s justice system.

As of June 2023, at least 52 lawyers reportedly faced legal action since the 2021 coup, although the actual figure is likely to be much higher as many cases of arbitrary arrest and detention are not reported. Other nongovernmental groups estimate at least 100 lawyers have faced legal action since the coup. At least 32 currently remain detained.[23]

Inside the Junta’s Secret Courts

Soon after the coup and the announced state of emergency, the junta established military tribunals and special courts empowered to conduct summary trials. This coincided with a wave of arbitrary arrests, mainly of political opponents, activists, and protesters. The junta’s actions in 2021 to establish these courts mirrors the military government’s move to establish military tribunals and “People’s Courts” in 1989 under Gen. Ne Win.[24] These courts are thus not new judicial bodies but rather a return to previously established practices.

Special Courts

The junta’s “special courts” are courts closed to the public that are held inside prisons to fast-track some criminal cases or cases deemed to be “political,” thus bypassing due process safeguards nominally present in Myanmar’s regular criminal courts.

There was no official decree or announcement setting up the special courts. However, the creation of these courts overlaps with the junta’s first martial law order on March 14, 2021. The first order placed two Yangon townships under martial law and transferred all executive and judicial powers to the military commander in Yangon Region.[25] On March 15, a second martial law order extended martial law to four other townships in the city.[26] Under this system, the special courts were set up to adjudicate hearings outside areas under martial law that are subject to military tribunals.

Special courts have operated inside Insein prison in Yangon, Taungoo prison in Bago, Oh-Bo prison in Mandalay, Hinthada prison in Ayeyarwaddy Region, and elsewhere across the country. They are supposedly overseen by a civilian legal and judiciary body, but in practice, judges and prosecuting lawyers are appointed or approved by the State Administration Council.[27]

Most reported trials of political activists and protesters since the coup appear to have been carried out in special courts, although the actual number cannot be determined because the junta has not released any figures.[28] Police often do not file reports until detainees are charged, and because there is no official reporting system or access for the public, nongovernmental organizations collecting data on detentions do not receive timely information. The lightning speed convictions and secrecy of these special courts also makes it nearly impossible to independently monitor trials.

Participants in the special courts said they are typically makeshift areas within prisons that are cordoned off by tarpaulin or cloth. The “courtrooms” are basic, with a table and chair for the presiding judge and space for any junta officials who may be monitoring the proceedings.[29]

A lawyer outside Yangon Region explained the process inside a special court:

The police allow entry only to lawyers who have the power of attorney over cases, but only one lawyer, not the teams that we would normally work in. They have a list which shows the cases will have hearings that day so if you are on the list, you can go in. If you’re not on the list for the case, no entry is allowed.[30]

A lawyer who spoke to a nongovernmental organization about his experience described “courtrooms” set up opposite each other along a corridor inside the prison. “They are numbered with no reference to the relevant township names. The judges that arrive first sit at the first courtrooms. We waste time searching for the correct township court. Clients sit in the overcrowded corridor opposite the courtrooms, which are separated by curtains. It is noisy in the rainy season and hot in the summer during trials.”[31]

A lawyer elsewhere in the country said:

For those of us who are allowed to enter the special courts, there are very strict security restrictions. We also sign forms to not post about anything on social media, and we have to agree not to relay any outside information to the defendants. We also have to sign an agreement that says we will be charged and arrested if we break those agreements.[32]

Lawyers who can enter the prison courts told Human Rights Watch it was not unusual to see hundreds of cases tried inside a special court in just one day, in turn presenting challenges for lawyers to adequately represent their clients.[33]

Hearings can be called last-minute and are conducted in an ad-hoc manner that does not follow any semblance of due process. This appears purposely orchestrated by junta officials not only to limit access to legal representation, but also to enable quick convictions with severe penalties for the accused.

Military Tribunals

For people arrested in areas under martial law, their cases are not heard in special courts, but in the entirely opaque system of military tribunals. The proceedings are closed to the public, inaccessible to lawyers, and lack any independence from the military. Military tribunals are presided over by military officers who have no prior knowledge or training in law.

Under Martial Law Order No. 3/2021, issued on March 15, 2021, military tribunals can issue death sentences or prison sentences with hard labor for unlimited years. Only the chair of the State Administration Council is empowered to acquit, reverse, or consider any appeals in response to a sentence handed down by the tribunals. [34] Thus far, no appeals are known to have been considered inside military tribunals, let alone a result in acquittals.[35] Apart from the military’s occasional and limited reporting of individuals who have received the death sentence or lengthy prison sentences with hard labor, there is no other information about those sentenced inside military courts.

For example, the military on July 25, 2022, reported the execution of four men in the country’s first death sentences carried out in over 30 years. The men put to death were Phyo Zeya Thaw, 41; Kyaw Min Yu, known as “Ko Jimmy,” 53; Hla Myo Aung; and Aung Thura Zaw, all of whom were convicted by military tribunals.[36] A military tribunal sentenced Ko Jimmy and Phyo Zeya Thaw to death on January 21, 2022, under Myanmar’s overbroad Counter-Terrorism Law of 2014. Hla Myo Aung and Aung Thura Zaw were convicted in April 2021 for allegedly killing a military informant. The junta captured all four men in townships under martial law and summarily tried them in military tribunals at Insein prison in Yangon. As of April 2023, military tribunals in Myanmar have sentenced at least 152 people to death since the February 2021 military coup, including 42 in absentia.[37]

In townships where martial law has been declared, military officers carry out all executive and judicial powers, and civilians are tried inside the military tribunals for any of the 23 violations listed in the martial law order. These include alleged crimes such as “high treason” under section 122 of the Criminal Procedure Code, incitement against the junta under section 124-A of the Penal Code, or to “cause fear” or “spread false news” under section 505A of the Penal Code.[38]

Undermining Right to a Legal Defense

In some townships where the junta has declared martial law, special courts operate alongside military tribunals in the same locations within the grounds of a prison complex, such as at Insein prison in Yangon. Individuals arrested in a township under martial law could be taken and detained at Insein prison. The person could then face multiple charges for the same offense: in a military tribunal due to where they were arrested, in a special court due to where they are being detained, and in multiple other jurisdictions depending on where the alleged crime occurred.

Lawyers said that challenges for defending those arrested were further compounded by the junta charging individuals both in special courts and military tribunals where the lawyers cannot enter. It is also problematic for both the lawyers and their clients when the defendant is charged in special courts in more than one township—they cannot attend hearings or trial dates set on the same days and same times but in different locations.

A legal adviser to a nongovernmental organization said:

How are they choosing who is going to the military court? We don’t really know, and it is not consistent. The military tribunals have power to try civilians accused of violating certain criminal provisions in addition to the anti-terrorism law and various other laws, but it is not a military court of law.… Another thing we consistently see is that defendants face charges before military tribunals and special courts simultaneously. So, they are charged for the same conduct under the same legal provisions, but in two different courts and the proceedings in the two courts go on simultaneously. It’s total chaos.[39]

For example, one of the men executed on July 25, Phyo Zeyar Thaw, was a lawmaker in the NLD government. He was charged and convicted by a military tribunal in Insein township, despite being arrested in Dagon Seikkan township—at the time, under martial law.[40] He also faced terrorism charges in a special court in Botahtaung township, but he was executed before the other case was brought to trial.[41]

Although special courts were being held at Insein prison, military tribunals were occurring alongside the special court proceedings.

On April 29, 2021, the junta amended the 2016 Legal Aid Law to remove the right to legal aid services during pretrial detention for criminal cases. The amendments to section 3(b) of the Legal Aid Law removes terms that bind the law to international standards. The revocation of section 3(e) means detainees can now be held indefinitely.[42] Section 4(i), which previously stated that legal aid providers were allowed “to act independently in accordance with the Law and to protect them [suspects],” was also removed.[43]

Lawyers found that providing legal aid services could result in themselves being arrested, detained, and charged under the Penal Code. All the lawyers with whom Human Rights Watch spoke to for this report said they had stopped pro-bono and legal aid services for fear of being arrested. However, broader legal aid services are available and have reached several thousand defendants, albeit in more limited circumstances and at a smaller scale than prior to the coup.[44]

Junta authorities permit lawyers to speak to their clients only on the day of the hearing, and often deny requests from lawyers to see their clients in prison. As discussed below, defendants have no right to confidential communications with their lawyers, and guards are typically present during the brief meetings permitted.

In higher-profile cases, such as that of NLD leader Aung San Suu Kyi, defense lawyers may be present during trials but are restricted in how they can question or cross-examine witnesses. For instance, lawyers told Human Rights Watch they are often prohibited from questioning witnesses or even presenting material evidence that could prove their client’s innocence. Some lawyers said they were told to stop asking questions if junta officials present at the trial did not like their “tone.”

One lawyer said:

In high-profile cases, the military intelligence units will come and monitor you when you meet with your client. They will monitor everything, more so as the trial begins. But if you ask anything slightly controversial, they will stop the lawyers from continuing to talk either on behalf of their client or during cross-examination, and they will note down your name to threaten you. I guess the threat is that you could also be arrested at any time. Sometimes cross-examination doesn’t even happen. It’s near impossible to challenge what they present as evidence, and we never get to have a defendant released on bail.[45]

In Mandalay Region, Bago Region, Hinthada in Ayeyarwaddy Region, Myeik in Tanintharyi Region, and the capital, Naypyidaw, police have placed gag orders to prevent lawyers from speaking publicly about political cases in the special courts. Lawyers are required to sign a paper at the entrance to the prison agreeing not to speak about what they see inside or to report what occurs during the special court proceedings.[46] Junta authorities placed Aung San Suu Kyi’s lawyer, Khin Maung Zaw, on a gag order, and apart from announcing his apologies for not being able to discuss the proceedings of the various charges against her with the media, he has complied with the order.[47]

A lawyer based in Yangon said none of the standard procedures for fair trials were observed in the special courts:

Normally before we start preparing for a case, we have to make a copy of everything. We also have to check which witnesses the police have interrogated, what their statements are, which physical evidence they are keeping. Now, all those things have changed. Cases are no longer charged or prepared by the police anymore. The military handle all of those and the police have to follow their orders and instructions.[48]

Defense lawyers may be present in special courts, but they say they act more frequently as “brokers,” asking for clemency and attempting only to reduce their client’ sentences as they are prohibited from presenting evidence to counter any charges, or from cross-examining even their own clients.[49]

No Privileged Communications

Meetings between lawyers and their clients in prison are limited in duration to 15 minutes, and subject to the conditions that prison guards or armed police and junta officials are present and that conversations are noted down or recorded by junta officials who are present during all meetings between the lawyer and their client.[50] Lawyers noted that prior to the coup, their clients were afforded a private 30-minute meeting with their lawyers.

The Yangon-based lawyer described the impossibility of preparing a defense because of the special court restrictions. She said:

For political cases, we have no privacy and can’t even meet with clients without someone's eyes upon us. There are always at least four or five police in the room, and often they are armed. We have to discuss some part of the case inside the courtroom. Even then, there is still a police officer or prison guard near us. So, it is really difficult to discuss cases with clients. Before all of this, we had the right to privately meet with our clients. We had laws and rules and regulations. And now, we have nothing. The junta don't care about laws.[51]

The junta introduced several measures by decree under the state of emergency, bypassing parliamentary processes, that directly erode the rights to a legal defense for individuals facing criminal investigation and prosecution for alleged terrorism offenses and crimes against the state. These measures and the junta’s arbitrary application and amendment of the laws are incompatible with fair trial standards, have destroyed any remaining trust in the legal system.

Lawyers working in Yangon, Mandalay, Mawlamyine, and Magway said their clients frequently displayed physical evidence of beatings and other torture while in custody.

Because so many defense lawyers are in hiding, detained, or are unable to take on political cases due to the Legal Aid Law amendments, the individual lawyers who remain practicing are often taking on hundreds of cases. One lawyer said, “We’re facing a situation where the ratio of available lawyers to represent prisoners is way too low. It is exhausting and becoming a burden and our numbers are dwindling now.”[52]

Lawyers also described how suspects’ cases are now prepared under the junta’s arbitrary processes. A lawyer said:

Some of the people I’m representing had to spend their time in the interrogation room up to three or four days in a row … They get beat up in the room during the interrogation and they are left until their wounds are healed and the information is gathered from them. Once that’s been done, they send them to the prison for processing. So, they send the person to the prison but their testimony from torture, together with their fingerprints and other personal details are sent to their respective district’s police stations.[53]

The lawyer said that only after the “confession” was extracted, would police process charges for the case:

In normal practice, they are supposed to get witness testimony as well, but they don’t do that now. Instead, they create evidence for their case based on the defendant’s interrogation testimony, which is often a result of torture. The prosecutors have never even met the defendant before the trial, and they create the case as both witness and plaintiff. They only meet the defendant on the first court hearing—but the case is already decided based on the interrogation ... I am starting to see corruption seeping into the system quite openly. It is becoming more and more obvious now. Bribery is playing a large role in whether my clients get a lenient sentencing or a severe one.[54]

Many of the lawyers interviewed by Human Rights Watch reported feelings of despair and inadequacy as they tried to do their jobs, saying that corruption and bribery commonplace prior to the coup had been worsening. A lawyer said:

I can’t help any of the [prisoners] as an attorney. Money is what matters the most inside the walls of the prison. Everything inside the wall is horrible; the food; the medicine—everything is bad. If you can’t bribe the guards, you’re stuck doing horrible chores like cleaning the toilets. When my client is visibly tortured or harmed, all I can do is file a complaint, and even then, it’s most often a verbal complaint. The most helpful thing I can do right now is sneak my clients some money so that they can avoid a beating next time—that’s the most helpful I can be as their attorney.[55]

Arrests, Beatings, and Mistreatment of Lawyers

Since the coup, junta authorities have arbitrarily arrested lawyers for their alleged role in either anti-coup activities or for defending suspects in political cases. Junta security forces have taken lawyers into custody in their homes, at their offices, on prison compounds, and after they have attended court proceedings. While in detention, police frequently deny lawyers their basic rights, and some lawyers have reported being mistreated and tortured.

Currently, 32 lawyers remain in detention, with most facing charges for incitement under section 505A of the Penal Code.[56] They are also increasingly being charged—without basis—under the amended Counter-Terrorism Act on allegations of terrorism or financing terrorism.

Beatings and Mistreatment of Lawyers

On June 29, 2022, security forces arrested three lawyers representing separate political cases in Mandalay. Police arrested Tin Win Aung, Thuta, and Thae Su Naing as they returned from separate court proceedings inside Oh-Bo prison.[57] Tin Win Aung and Thuta were representing the high-profile case of Wai Moe Naing, a well-known student activist accused of five counts of incitement under section 505A of the Penal Code and other charges for which there was no credible evidence, including murder, abduction, and robbery.[58]

According to media reports and other sources familiar with the lawyers’ arrests, the security forces severely beat all three lawyers during interrogation. Multiple sources said Tin Win Aung suffered serious injuries, including a broken arm and leg, and had to have a feeding tube inserted into his stomach due to the injuries he sustained during the beatings.[59] “They were all tortured but not as bad as U Tin Win Aung,” one source said.[60]

Another source detailed Tin Win Aung’s torture:

His legs were stretched and cuffed in a wooden shackle. Then they would roll a heavy stick across his tibia, then they stand on his legs, so his tibia bones were fractured. They kicked his chest and back. There were also injuries like being cut with knives. His legs bones were mostly fractured. From the impact of a kick into his chest and back, his lungs were damaged too. [61]

He described Tin Win Aung’s condition four months after the arrest:

Right now, his condition is stable, but they tortured him badly … They sent him to the prison’s hospital wing, but because the prison hospital didn’t have the facilities he needed, he was moved to Mandalay hospital to get treated for his injuries.[62]

A legal colleague of Tin Win Aung’s said he had incurred the wrath of prison officials for contesting in court the unsatisfactory evidence provided by prosecutors against his client.[63] Without adequate legal representation and his own lawyers detained, a junta court sentenced the activist, Wai Moe Naing, to a total 34 years in prison.[64]

Targeting of Lawyers Representing Political Cases

The lawyers most vulnerable to being targeted by the military or police are those providing legal assistance to those directly within their communities. A lawyer who worked in southeastern Myanmar represented several protesters in political cases. Local government officials, shortly after the coup, said she was arrested because of her willingness to represent political cases.

She said the police claimed they received a tipoff that she was providing financial assistance to the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM), a strike movement of civil servants protesting the coup, and therefore was helping to lead “protests and riot, undermining public tranquility.”[65] Police also accused her of purchasing medical supplies and protective wear for protesters, but she believed they targeted her for representing political cases in her township.[66] She said for weeks leading up to her arrest, police and a township judge who presided over some of her cases had threatened her not to take on political cases.

The military arrested her on October 18, 2021, during a dawn raid. Soldiers came to the lawyer’s house around 4 a.m. and surrounded her home with about 20 military trucks. They accused her of organizing a private lawyers’ group on social media and representing deposed local government officials. She said:

They cuffed me from behind as soon as I said “yes” when they asked me my name. Then they blindfolded me and took me away, to what I assume was a police station. When we got there, I was ordered to kneel down and raise my head for a photograph—they kept my hands tied behind my back. They kept me at the station for a while, then they came to take me to the interrogation place in blindfold … I was blindfolded and forced to kneel down with my arms tied behind my back and questioned like that for hours each time.[67]

For 18 days, police kept the lawyer in an undisclosed location in Tanintharyi Region. Junta security forces interrogated her at a separate military interrogation center for eight days.[68] She said her interrogators wore military uniforms and threatened to beat her. They denied her food and water during the interrogations. Police denied the lawyer bail despite her colleagues’ multiple requests during the more than two weeks she was held without charge.

In November, her trial began at the special court inside the township prison where she was taken after the police holding cell. A colleague told Human Rights Watch that police had intimidated other defense lawyers so thoroughly that no one felt safe taking her case, therefore requiring the detained lawyer to defend herself during the trials despite having no access to information outside the prison.[69] The police offered witnesses who were all members of the township police force.

Despite a lack of credible evidence, a judge, on March 18, 2022, found the lawyer guilty of incitement under section 505A of the Penal Code and sentenced her to two years’ imprisonment with hard labor.[70] She said: “When I was sentenced in front of a judge for my case, the judge looked at me and said, ‘Didn’t I tell you and warn you not to get involved in these matters? Now, aren’t you in trouble?’”[71]

Her sentence was commuted during a prisoner amnesty, and she was released less than a year after beginning her prison term, but the conviction against her has not been quashed.

In June and July 2022, junta authorities arrested several lawyers in Sagaing and Mandalay Regions for their role in representing high-profile political cases.

Military authorities arrested lawyer Moe Zaw Tun at his home in Monywa on July 20, according to sources close to him. Moe Zaw Tun was representing a former NLD minister for Sagaing Region chief minister and NLD central executive committee member Myint Naing. Legal sources said that Moe Zaw Tun was charged under section 50(a) of the Counter-Terrorism Law for allegedly helping finance Myint Naing’s anti-coup activities.[72]

The same week of Moe Zaw Tun’s arrest, the military arrested two other lawyers in Monywa, Than Tun and Chan Myae. Than Tun worked as defense counsel for those charged under section 505A of the Penal Code. Chan Myae was providing free legal aid services to individuals arbitrarily detained since the coup. Both were charged under section 505A.[73] As of April 2023, both lawyers remain detained.

On May 27, 2021, police arrested lawyer Aye Yar Lin Htun[74] shortly after she attended a hearing at the Hinthada District court in Ayeyarwaddy Region where she was representing several political cases.[75] Police detained her in the jail cell area of the courtroom, stating that they were charging her under section 505A of the Penal Code for allegedly being a ringleader for anti-coup demonstrations that took place in February 2021. A day after being detained, on May 28, 2021, police took Aye Yar Lin Htun to the Hinthada police station and then transferred her the same day to Hinthada prison.

Friends and relatives said they are deeply worried for Aye Yar Lin Htun’s health as she suffers from several congenital illnesses including diabetes. The health care available in prison is often inadequate even for basic medical conditions and relatives said that their numerous requests for Aye Yar Lin Htun to receive better care were often outright denied.[76]

The authorities finally allowed Aye Yar Lin Htun a hospital visit two weeks after her initial detention. The source said:

The prison authorities finally gave permission to get her medical care, so they took her in a police jail truck, cuffed, in the middle of night to the hospital. They didn’t allow us to go near her … There was a heavy police presence around her and after the examination by the physician, he said she needed to be hospitalized immediately but the prison authorities would not allow it and demanded she be brought back to the prison.[77]

Friends of Aye Yar Lin Htun said she may have been targeted due to her membership in the Independent Lawyers’ Association of Myanmar, which the junta considers to be affiliated with the NLD.[78] On September 15, 2021, a special court sentenced Aye Yar Lin Htun to three years’ imprisonment.

Surveillance and Threats against Lawyers

All the lawyers who spoke with Human Rights Watch said anyone working on politically sensitive cases were surveilled by the junta. Undercover police or intelligence branches kept them under surveillance outside the courtrooms. One lawyer said:

We are heavily surveilled. We’re told [by the judges] that we can’t ask witnesses certain questions. We receive threats from prison officials, intelligence units, and random people. They take our names down, take photos of us, come to our houses, and watch from outside. The lawyers who are going into the special courts inside the prisons are harassed the most. They have all our details so there is a constant threat hanging over us. …

Both soldiers and police can follow us but generally it’s the intelligence units that are worrying. They don’t wear uniforms so of course, sometimes it’s hard to tell who they are. They don’t need to come into the homes, they often record who’s coming and going from each ward. If they do want you specifically, they come at night to “talk” to you, but really, it’s to threaten.[79]

The lawyers all gave accounts of the police and military making threatening or vaguely threatening remarks to them when they went into the prisons to see their clients or while defending clients during special court hearings. One lawyer said that a member of the security forces told a group of lawyers: “Just you all wait. We are going to come and get all of you and put you all in the cells.”[80] Another lawyer described having weapons aimed at her by junta security forces in the courtroom for “asking too many questions.”[81] She said armed soldiers were regularly present during court proceedings inside prisons.

The lawyers who spoke with Human Rights Watch all expressed fear for their security and safety due to junta threats against defense lawyers both inside and outside the courtroom. They said that they needed to be careful how they presented statements during special court proceedings to avoid retaliation from the presiding judge or junta officials present in the courtroom. A Yangon lawyer said:

In the courtroom, I now have to worry about not getting myself detained rather than speaking the truth. This is especially true when I have to represent political cases. Everyone at the court knows who I am, and the court has all my credentials and personal information. The junta can detain me at any time, and they can and will make up any reasons they want.[82]

A lawyer from Ayeyarwaddy Region said she witnessed intelligence officials threatening a colleague during a special court proceeding after objecting to her colleague’s line of questioning:

There was a case that started off with three people getting arrested but one of them died during interrogation, so only two people were put on trial. When we looked at the case file, it said three and when we asked further about where the third person was, the [junta] intelligence officials tried to pass it off as a health issue. When the main defense lawyer revealed the death of the third prisoner during the hearing and that she was unsatisfied with the reason provided, she was told she should keep her mouth shut. The attending officials said that they could arrest her and charge her under Penal Code section 505A. I heard this with my own ears. They were openly threatening lawyers right inside the court proceeding.[83]

Lawyers Charged for Alleged Anti-Coup Activities

Lawyers have faced charges related to their alleged involvement in anti-coup activities, such as participating in protests, sharing anti-military information on social media, and supporting resistance groups. In some cases, junta authorities have accused lawyers of being members of the same resistance groups as their clients or participating in their client’s alleged crimes.

Police arrested lawyer Nay Sithu Zaw from his home on August 8, 2021, the day after he gave a speech in Mandalay commemorating the “8.8.88” anniversary.[84] His wife, who was arrested with him, was released two days later. A colleague familiar with the case said that prosecutors accused him of direct involvement in anti-coup activities based on anti-coup leaflets found in his car during his arrest. Nay Sithu Zaw denies such involvement.[85] However, he was also representing a number of political cases of students arrested in Mandalay during anti-coup protests.

According to the colleague, Nay Sithu Zaw was charged under section 505A of the Penal Code and sentenced to three years’ imprisonment on June 9, 2022. He faces additional charges under section 17(1) of the Unlawful Associations Act for allegedly being tied to anti-coup militias the junta had declared as terrorist organizations.[86] The colleague said:

We met in July 2021 and that’s the last time I saw him before he got arrested. He was joking about being arrested and going to prison … Once I heard about his news of capture, I was really sad.[87]

The police record of Nay Sithu Zaw’s arrest, which Human Rights Watch reviewed, notes that a sheriff from the Aung Pinlal police station in Mandalay was a witness for the prosecution, and that Nay Sithu Zaw was charged with section 505A of the Penal Code for “attempting to disturb the governing power of the country; attempting to disturb the peace and tranquility of the country; involving in, and inciting riots and protests that endangered the livelihood of the general public and taking part in military training from a terrorist organization.”[88]

On December 28, 2022, a special court in Mandalay sentenced defense lawyer Ywet Nu Aung to 15 years in prison for violating section 50j of the Counter-Terrorism Law.[89] Police charged her with “financing terrorism” for donating approximately US$110 to the People’s Defense Forces, the armed anti-junta resistance groups the junta has declared are “terrorist groups.”[90] However, Ywet Nu Aung was representing several high-profile cases including of the ousted NLD Mandalay regional chief minister Zaw Myint Maung. Ywet Nu Aung was also a regional-level NLD member and a legal adviser to the party.

Police arrested Ywet Nu Aung on April 27, 2022, after she left a special court hearing in Mandalay’s Oh-Bo prison, where she was representing the former NLD chief minister of Mandalay.[91] A source familiar with her case said the junta authorities had so thoroughly scared and intimidated other lawyers from representing Ywet Nu Aung that she was left with no other option than to represent herself from inside prison.[92]

Lawyers in Hiding

Since junta authorities have targeted lawyers for arrest due to their alleged support for public protests against the military coup, many have gone into hiding. On February 15, 2021, more than 40 lawyers were charged in absentia for sedition under section 505(b) of the Penal Code following their participation in protests in Mandalay.[93] Subsequently, many of these lawyers went into hiding following the warrants for their arrests and the arrests of their colleagues.

One senior lawyer described why she went into hiding:

I was charged with section 505A of the Penal Code and 50(j) of the amended Counter-Terrorism Law for donating money to the People’s Defense Forces … They opened cases against me at district and regional courts. I had to leave all my cases with my team and junior lawyers, but in the end, they arrested one of my junior lawyers in place of me.[94]

Another lawyer originally from Mandalay said she continued to work remotely but remained in hiding after the arrest of her colleagues. The lawyer said she ran away after police and soldiers turned up and surrounded her home in July 2021. The police apparently targeted her for arrest after coercing a fake confession from her colleague during interrogation of her role in anti-coup activities. She said that her colleague “had to sign a blank paper. After it was signed, they just wrote whatever they wanted and submitted it as evidence.”[95]

Another senior attorney, who fled Myanmar in February 2023, said that shortly after the second anniversary of the coup that she was alerted that her name was on a list of arrest warrants that charged her under section 52A of the Counter-Terrorism Law for allegedly “financing terrorism.” Her sources said that police in her home township had opened the case against her in February 2022, of which she was unaware. She left the country just as her family home was being raided.

The lawyer, an NLD member and township administrative secretary of the party, said she had been expecting the junta to come for her much earlier since she had represented hundreds of political and criminal cases in special courts. These included members of parliament, the NLD’s executive committee members, and others arrested under politically motivated charges since 2021. She said:

I know of many lawyers who are arrested, and I have even seen a detained colleague while I was working in a special court, but I couldn’t get any information from her. She wouldn’t tell us anything about her detention conditions or even the reason why she can’t tell us. I guess she was afraid of the consequences such as torture or getting more charges if we speak about it publicly. For me, I would want people to speak out for me as much as they would like. If I have to spend the rest of my life inside prison walls, I would want people to know about me.[96]

International Standards: Right to a Lawyer, Fair Trial

Role and Responsibilities of Lawyers

The United Nations Basic Principles on the Role of Lawyers (the “Basic Principles”) sets out standards that governments should adopt in their national legislation and standards to ensure the proper role of lawyers.[97] These principles address access to lawyers and legal services, special criminal justice safeguards, and lawyers’ freedom of expression and association.

Myanmar judicial authorities have routinely acted contrary to the Basic Principles. Criminal suspects are entitled to have the lawyer of their choice “protect and establish their rights and to defend them in all stages of criminal proceedings.”[98] Governments should ensure that “all persons arrested or detained, with or without criminal charge, shall have prompt access to a lawyer,” at least within 48 hours of arrest or detention.[99]

The Basic Principles also set out specific government guarantees for lawyers, including ensuring that:

- Lawyers “are able to perform all of their professional functions without intimidation, hindrance, harassment or improper interference” and do “not suffer, or be threatened with, prosecution … for any action taken in accordance with recognized professional duties, standards and ethics.”[100]

- Lawyers will be adequately safeguarded by the authorities when “the security of lawyers is threatened as a result of discharging their functions.”[101]

- Lawyers are “not … identified with their clients or their clients' causes as a result of discharging their functions.”[102]

- No court or administrative authority before whom the right to counsel is recognized can “refuse to recognize the right of a lawyer to appear before it for his or her client unless that lawyer has been disqualified in accordance with national law and practice and in conformity with these principles.”[103]

- Lawyers “enjoy civil and penal immunity for relevant statements made in good faith in written or oral pleadings or in their professional appearances before a court, tribunal or other legal or administrative authority.”[104]

- Competent authorities provide “lawyers access to appropriate information, files and documents in their possession or control in sufficient time to enable lawyers to provide effective legal assistance to their clients. Such access should be provided at the earliest appropriate time.”[105]

- “[A]ll communications and consultations between lawyers and their clients within their professional relationship are confidential.”[106]

Right to a Lawyer as a Fair Trial Right

An individual’s right to a fair and public trial by an independent and impartial tribunal in the determination of any criminal charge against them is enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights[107] and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.[108] The ability of lawyers to exercise their functions freely and independently is central to the capacity of the justice system to protect fair trial rights in general. Lawyers need confidential access to their clients to be able to provide prompt, unhindered, and confidential legal advice to ensure the right to a fair trial. Although Myanmar is not a party to the covenant, the right to a fair trial is recognized as customary international law and a responsibility of Myanmar as a UN member state.

The UN Human Rights Committee, in its General Comment No. 32 on the

right to a fair trial, sets out the role of the lawyer in ensuring the right including the relations between lawyers and their clients. In particular, the committee emphasized that there is a right to prompt access to a lawyer, and that:

Counsel should be able to meet their clients in private and to communicate with the accused in conditions that fully respect the confidentiality of their communications. Furthermore, lawyers should be able to advise and to represent persons charged with a criminal offence in accordance with generally recognized professional ethics without restrictions, influence, pressure, or undue interference from any quarter.[109]

The junta’s amendments to various laws have contributed to the deprivation of the right to a fair trial since the February 2021 coup. Revisions to laws that interfere with or deny a lawyer’s access to persons in detention, deny confidentiality of privileged communications between lawyers and their clients, hinder access to investigation files, deprive defendants of the right to call witnesses, and to challenge witnesses against them on an equal basis, all violate the right to fair trial protected under international law. [110]

Acknowledgments

This report was researched and written by Manny Maung, a researcher in the Asia Division of Human Rights Watch. Several individuals from non-governmental organizations with legal expertise on Myanmar provided research assistance for the report. “Ko Htike” provided additional research assistance. This report was edited by Danielle Haas, senior editor of Program, Patricia Gossman, associate director for Asia, and Elaine Pearson, Asia director. James Ross, legal and policy director, and Tom Porteous, deputy program director, provided legal and programmatic review. Shayna Bauchner, Regina Tames, and Kyle Knight provided additional reviews. Production assistance was provided by Christopher Choi, associate with the Asia Division.

Human Rights Watch acknowledges and thanks the brave lawyers and people inside Myanmar who cannot be named, but provided crucial information and their time for this report.