The government of Morocco must act now to end impunity for the security forces and enhance judicial independence if it is to cement the legacy of the country’s truth commission, Human Rights Watch said in a new report released today.

After nearly two years of investigations into abuses committed between 1956 and 1999, the state-appointed Equity and Reconciliation Commission (ERC) is to submit its final report and recommendations to King Mohamed VI at the end of this month.

Morocco’s commission, the first of its kind in the Mideast and North Africa, represents a historic step in acknowledging the violations committed during the 38-year reign of the late Hassan II, – including hundreds of cases of “disappearances,” and thousands of arbitrary detentions.

The ERC, which has reported receiving between 25,000 and 30,000 applications for compensation, will determine the forms and amounts of reparation the state is to provide victims.

“The ERC seems to have done a serious job of excavating past abuses and of honoring victims,” said Sarah Leah Whitson, executive director of Human Rights Watch’s Middle East and North Africa division. “But it is now up to the state to ensure an important aspect of providing reparation: taking steps to ensure that what the victims suffered can never happen again in Morocco.”

Moroccan authorities have presented the ERC as a keystone in the process of consolidating democracy and the rule of law. But this claim is clouded by continuing patterns of human rights violations, despite the overall advances over the last fifteen years. Authorities continue to prosecute journalists for critical writings and to break up peaceful demonstrations. Arbitrary arrests continue of suspected independence activists in the disputed Western Sahara. And in the wake of the 2003 suicide bombings in Casablanca, Moroccan security forces rounded up hundreds of suspected Islamists and subjected them to ill-treatment during interrogation. The men were sentenced to prison terms after unfair trials.

If today’s abuses are not on the scale of those committed in the 1960s and 1970s, they show that the mechanisms facilitating the earlier violations – security forces acting with impunity, courts that lack independence, and repressive legislation – are hardly a relic of the past. These ongoing abuses fall outside the ERC’s mandate, but they weigh on its task of recommending ways to prevent abuses in the future.

The ERC’s full report will go to the king. It is not yet known how much of it will be made public. The ERC has been investigating not only the general history of repression in Morocco but also individual cases, notably the hundreds of persons whom the security forces “disappeared” in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s and whose fate remains unknown. One measure of the ERC’s success will be the extent to which it provides families concrete information about the fate of their “disappeared” relatives.

Another test of the ERC will be its stance toward the impunity of those who committed grave abuses in the past, whose ranks reportedly include some who hold government posts today. While the ERC is barred from publicly naming perpetrators, it should advocate that authorities charge or sanction perpetrators of grave violations when the evidence warrants, Human Rights Watch said. The ERC should also disclose publicly the extent to which past and present officials cooperated in its investigations, and to disclose the impact of any non-cooperation on its search for truth.

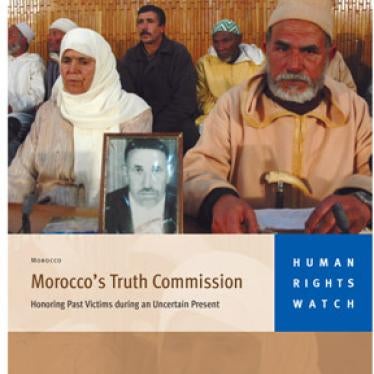

In its 48-page report, entitled “Morocco’s Truth Commission: Honoring Past Victims in an Uncertain Present,” Human Rights Watch directs most of its recommendations to Moroccan authorities, who are the ones ultimately responsible for safeguarding against future abuses and fulfilling the right of past victims to compensation. Authorities should:

• Direct a high-level office to monitor and evaluate, in a public and ongoing fashion, the state’s implementation of the recommendations made by the ERC.

• Commit to providing a public response to each of the ERC’s recommendations, specifying a plan and timetable for compliance, or an explanation why the government does not intend to comply.

• Ensure that all evidentiary material collected by the ERC is turned over to judicial authorities, in contemplation of bringing charges where the evidence warrants.

• Bring to justice those individuals identified by the ERC as having committed grave human rights violations, where sufficient evidence exists to bring them to trial.

• Refrain from declaring any amnesty or similar measures that would exempt from prosecution persons implicated in carrying out “disappearances” or other grave violations of human rights; any eventual measures of clemency should come after individual responsibilities have been established, not before.

• Consider extrajudicial sanctions, such as dismissals from posts, for public officials against whom solid evidence exists of participation in grave abuses, where the post they occupy enables them to continue to violate the human rights of others.

• Publicly remind victims and their beneficiaries of their continuing right to obtain redress from courts, which has not been compromised by the existence of the ERC or by their acceptance of reparations from the ERC.

• Ensure a legal and administrative framework that preserves, and ensures easy public access to the archival material generated by the ERC, except that which should legitimately remain classified.

• Acknowledge that grave human rights abuses in the period under study by the ERC were systematic and ordered at the highest levels of the state, and offer official statements of regret to the victims and their families.

“Truth commissions are about learning the lessons of the past to apply them to the future,” said Whitson. “Nothing will do more to ennoble the legacy of the Equity and Reconciliation Commission than if the Moroccan state acts now to curb the impunity, past and present.”