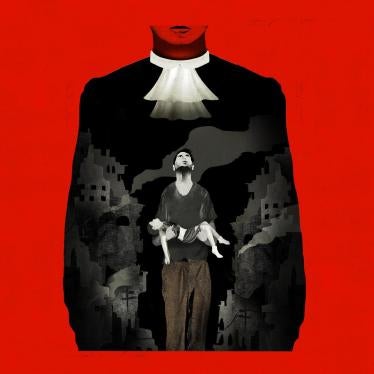

As Croatia prepares to begin EU membership negotiations, the European Union should insist that Croatian courts make clear progress in trying war crimes cases, Human Rights Watch said today.

On December 17, EU heads of states and government, acting as the European Council, decided that membership negotiations with Croatia would begin on March 17, 2005 provided that Croatia cooperates fully with the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia in The Hague by that date. There are no comparable conditions for progress on domestic war crimes trials, which have been plagued by bias, lack of professionalism in the courts and inadequate police cooperation.

“Proper domestic war crimes trials in Croatia simply won’t happen without EU pressure,” said Rachel Denber, acting Europe and Central Asia director at Human Rights Watch. “The EU needs to include domestic war crimes trials in the accession benchmarks it sets for Croatia.”

The transfer of cases to domestic courts in the region is an integral part of the completion strategy for The Hague tribunal, which must conclude all investigations by the end of 2004 and all trials by the end of 2008.

In a study of war crimes trials in Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Serbia and Montenegro, Human Rights Watch found trials in the region suffer from ethnic bias on the part of judges and prosecutors, poor case preparation by prosecutors, inadequate cooperation by the police in the conduct of investigations, poor interstate cooperation on judicial matters, and ineffective witness protection mechanisms.

In Croatia, Human Rights Watch found the additional problems of trials being conducted in the absence of the accused, and the use of group indictments that fail to specify an individual defendant’s role in the commission of the alleged crime.

A hugely disproportionate number of cases in Croatia have been brought against the ethnic Serb minority, some on far weaker charges than cases against ethnic Croats. According to the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), in the first ten months of 2004, Serbs represented 23 of the 27 persons arrested, 85 of the 105 on trial, and 18 of the 20 convicted. Ethnic Serbs have also been convicted where the evidence did not support the charges. Problematic domestic war crimes prosecutions continue to impede the return of Serb refugees to Croatia.

There has only been one case in which a Croatian court properly tried a war crime committed against ethnic Serbs: the 1991 killing of Serb civilians around Gospic. As a result of this trial, a number of those responsible were brought to justice and convicted for the crime. Comparable war crimes committed in the Medak pocket, Vukovar, Zagreb (the murder of the Zec family), Lora, Pakracka Poljana, Korana bridge and Bjelovar have either not been prosecuted at all or have resulted in acquittals. In the Paulin Dvor case, only one person was convicted, although many others participated in the killings of 19 Serb civilians in that village.

By contrast, Croatian courts have found ethnic Serbs guilty of war crimes even for such acts as theft of bedclothes, plates, or an alarm clock from a house, as in the conviction of Ivanka Savic by a court in Vukovar, in January. No ethnic Croats have been indicted for similar offences, let alone tried or convicted. On September 8, in a particularly worrying development, the Supreme Court of Croatia confirmed the Savic judgment, despite glaring errors including the lower court’s failure to establish the facts sufficiently and correctly, and its distortion of the statement by a key witness.

“Until Croatia demonstrates it can try war crimes cases fairly, it won’t be possible to say that the rule of law has fully taken hold in the country,” said Denber. “The European Union must insist that Croatia apply fair trial standards, and it must be willing to suspend membership negotiations if clear improvements are not made.”

In an attempt to remedy shortcomings in past war crimes prosecutions, Croatia enacted legislative reforms in October 2003, permitting the transfer of war crimes cases from rural courts to more professional courts in Croatia’s four largest cities—Zagreb, Osijek, Rijeka and Split. So far, however, no cases have been transferred to the four designated courts, and only the court in Osijek has actually conducted war crimes trials. County courts in Vukovar, Zadar, Gospic, Karlovac, Bjelovar, Sisak, and Sibenik, continue to try all other cases.

Croatia also enacted a new witness-protection law in October 2003. Effective protection of witnesses is widely acknowledged to be a critically important precondition for effective war crimes prosecutions. However, as recently as June, the OSCE mission found that Croatia had yet to develop an adequate witness-protection program.