(Berlin, September 18, 2025) - The partners in Germany’s governing Christian Democrat-Social Democrat coalition have been sparring over the contents of a planned replacement of the Citizen’s Income social security benefit, with a “New Basic Income for Jobseekers.”

Although the specifics are still unknown, leaked details keep grabbing headlines. A proposed €5 billion annual cut to welfare spending, the number of Bürgergeld recipients the government claims are “total refusers” who just won’t comply with job-seeking requirements (23,000 people, or under 0.6 percent of the total 4 million claimants), and major planned changes to how the housing allowance will work. But focusing on these details misses a crucial point: how will the changes affect the lives and the rights of people receiving basic benefits now and in future, both in terms of the minimum subsistence level in German constitutional law (the Existenzminimum principle) and Germany’s wider human rights obligations?

Chancellor Friedrich Merz, a Christian Democrat, put it starkly: “We can no longer afford the system we have today. That means painful cuts.” On the Social Democratic side of the governing coalition, Federal Labor Minister Bärbel Bas retorted: “Claiming we can no longer afford the social security system and the welfare state is – pardon the expression – bullshit.” She has suggested finding the funds by increasing higher earners’ social security contributions.

The daily reality for many people with low incomes in Germany risks getting lost in this debate. Many people just can’t make ends meet. And this is where the impact of the cuts will be felt. Human Rights Watch, among others, has documented rising poverty and hardship, linked to gaps in the country’s social security system and growing low-wage economy.

Save the Children Germany’s recent publication of a survey of 1,000 parents shows alarming levels of worry among families. A quarter of all parents surveyed are concerned that they won’t be able to meet the costs of heating, housing, clothing and food in the next 12 months. In families with a monthly income below €3,000, 57 percent feel this way, a significant deterioration compared with last year’s findings. Seventy-six percent think the government’s plans to deal with child poverty are insufficient. The planned cuts will add to the anxiety of families choosing between heating or eating this winter.

Low-wage part-time work has burgeoned in Germany in the past two decades, with women, particularly parents and caregivers, most likely to be in such jobs. An increasingly punitive social security system is likely to increase the number of people seeking low-paid, insecure, temporary work to prove they are seeking employment.

These low incomes inevitably will need to be topped up by benefits, with the state effectively subsidizing a harmful low-wage economy. And as people in these jobs age, their low incomes and social security contributions will almost certainly lead to low pensions when they become eligible for them and will increase the already sizable gender pension gap that older women face.

Poverty for older people has already risen dramatically in Germany. Official statistics showed that 11 percent of people age 65 and older were at risk of poverty in 2005, but by 2023, that had risen to more than 20 percent. As a 71-year-old woman told us at a food bank in North-Rhine Westphalia: “The support from the government simply isn’t enough. Life is expensive. At home I stay under a blanket and drink tea, coffee, or soup to stay warm. There’s not much else to do.” At this rate, it will get worse for future generations of older people.

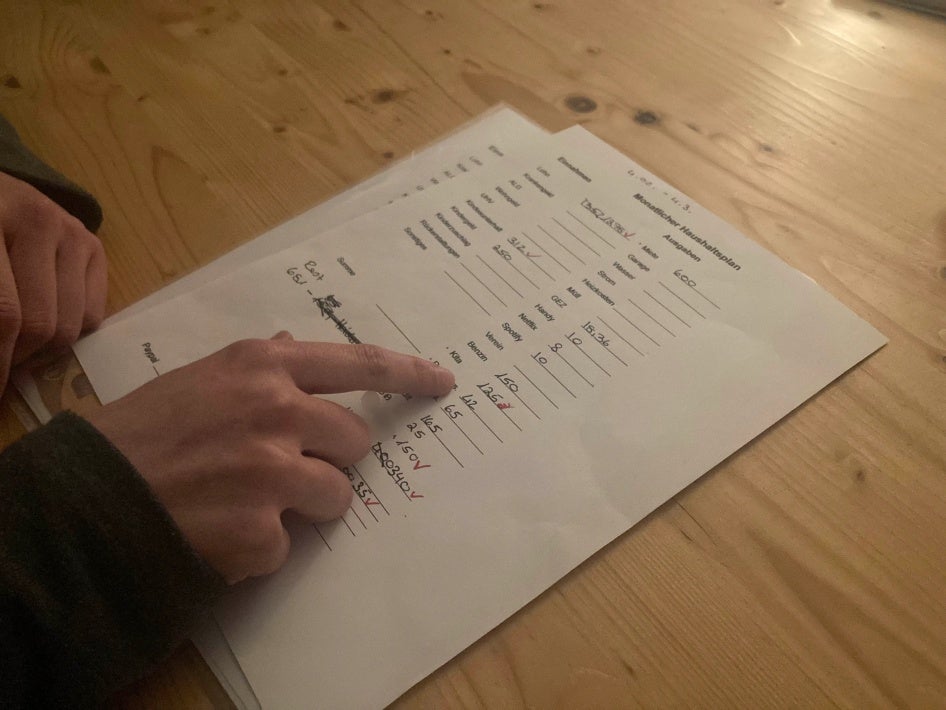

In addition to inadequate benefit levels, the process of applying for the Citizen’s Income or supplemental child allowance or one’s retirement pension can also be labyrinthine.

The German government is bound under international law to uphold the right to social security and the right to an adequate standard of living. Germany’s own constitution establishes the welfare state principle, and its constitutional jurisprudence has developed, over the years, clarity on the minimum subsistence level concept.

As the recently established Welfare State Commission, made up of nine federal ministries and state and municipal representatives, begins its work and the legislative debate takes shape, human rights—such as the rights to social security and an adequate living standard—should guide the discussion.

This will mean carefully assessing whether current social security payment levels do enough to advance the human right to an adequate standard of living, and not just whether they satisfy a formal statistical calculation of the minimum subsistence level. The experience of people living on low incomes, civil society research, and a government-commissioned study, strongly suggest they do not.

No one in Germany should be left without a decent standard of living. And yet, cutting welfare, and imposing tougher penalties on people deemed not to have complied, will mean precisely that.