This month marks 50 years since the arrival of the last of the Chagossian people in Port Louis, Mauritius. Over a period of eight years, the United Kingdom and United States had forced the entire indigenous population from their island homeland in the Indian Ocean to make way for a US military base on the largest of the islands, Diego Garcia.

To this day the UK, which still rules the Chagos archipelago as its last colony in Africa, prevents the Chagossians from returning. This is an ongoing crime. Most have lived in extreme poverty since.

Chagossians on the last boats in 1973 told Human Rights Watch about the suffering they have endured. Liseby Elyse, pregnant at the time, described sharing a cabin with pigs and horses. She lost her unborn child because of the trauma of being forced onto a boat, leaving her life and livelihood behind.

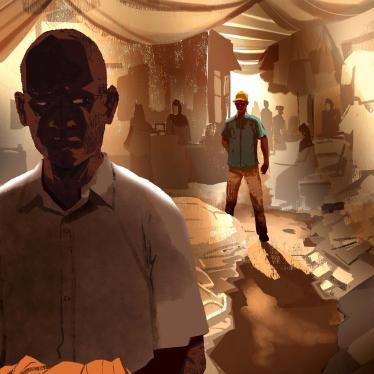

Rosemond Saminaden recalled their arrival in Mauritius in 1973, where they found themselves with nothing, not even a place to live. The Chagossians were offered an “abandoned estate occupied by animals”. After rejecting this, his family lived in a single room for 15 years.

All talked about experiencing profound suffering and loss, including what they call “chagrin”, the emotional devastation of being torn from their homeland.

As Human Rights Watch found in its recent report, That’s When the Nightmare Started: UK and US Forced Displacement of the Chagossians and Ongoing Colonial Crimes, the forcible displacement of the entire Chagossian people is a crime against humanity. For the US, Diego Garcia presented a strategic location, but they wanted an island without people for their military base.

To avoid having to report to the United Nations about its continued rule over Chagos and its colonised people, the UK, having reached a secret agreement with the US for the building of the base on Diego Garcia, declared that Chagos had no permanent population and went on to expel all inhabitants from the Islands that make up the Chagos archipelago.

The deportations were based on lies and driven by racism. As descendants of enslaved people brought to Chagos by French and British colonial rulers from East Africa and Madagascar, as well as of indentured labourers from South Asia, the Chagossians had lived on the islands for centuries. Over the past 50 years, they have fought for recognition and the right to return home. They have achieved significant legal victories but the UK, which still maintains control over Chagos, continues to deny them their rightful return.

Regrettably, African states have seldom publicly raised their voices in support of the Chagossian people. In a recent UN review of the UK’s human rights record, not a single African nation questioned the UK regarding its ongoing colonial crime against humanity in Africa. Yet, the plight of the Chagossian people is one that many African people can identify with. The disenfranchisement that Africans have endured as part of colonial legacies is embodied in the suffering that the Chagossians have endured at the hands of a cruel master and that has repercussions up to today.

In 2003, the African Commission on Human and Peoples Rights, sitting in Banjul, Gambia, adopted a groundbreaking report on the rights of indigenous people of Africa. The protection of the rights to land and natural resources are fundamental to the survival of indigenous peoples and enshrined in the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights.

Dispossession of land and natural resources is a major human rights problem, which the Chagossians know too well. The Working Group on Indigenous Populations/Communities established by the African Commission should turn its attention to the plight of the Chagossians and give meaning to the rights of the Chagossians under the African Charter.

In the past year, the UK and Mauritius have begun negotiations on the future of Chagos. Chagossians have not been invited to the table.

We have seen this also in the context of the Namibia-Germany reparations process to address Germany’s colonial genocide, where both governments continue to violate affected communities’ participation and representation rights despite international scrutiny.

The UK and US owe reparations to the Chagossians, which must be adequate and immediate. They need to ensure the unconditional right of every Chagossian to choose to return to their homeland, including Diego Garcia and the Chagos archipelago in its entirety. Both the UK and the US should restore the territorial integrity of all the islands to ensure the dignity and prosperity of the Chagossians, and provide guarantees that such crimes can never happen again.

Now is the time to bring an end to these crimes. And the African Union and African states should be publicly standing in solidarity with these indigenous people, survivors of an ongoing colonial crime against humanity.