I. Accelerating Deforestation

Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon has increased dramatically since President Bolsonaro took office in 2019—including a 22 percent jump in 2021 (to 13,000 square kilometers of rainforest cleared) over 2020, the highest since 2006 and more than triple the target that Brazil established in its National Climate Change Policy enshrined into law in 2009.[i]

This accelerated deforestation is driving the Brazilian Amazon towards a “tipping point” where vast portions of the rainforest will turn into dry savannah, altering weather patterns and water cycles across South America and releasing billions of tons of carbon into the atmosphere.[ii] Indeed, some deforested areas of the Brazilian Amazon are already releasing more carbon than they absorb.[iii]

Every year, fires linked to deforestation in the Amazon poison the air that millions of Brazilians breathe, with significant negative impact on public health, including thousands of hospitalizations.[iv]

II. Regressive Climate Action Plan

Brazil is one of the world’s top ten emitters of greenhouse gases, with emissions largely driven by changes in land use, including the clearing of forests.[v]

In its December 2020 update to the Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) to the Paris Agreement, Brazil reiterated the emissions reduction goals established in its 2016 plan rather than establishing more ambitious targets, as the Paris Agreement required. Moreover, the 2020 plan increased the baseline value against which reductions were to be calculated, thus allowing Brazil to appear to meet its targets while making significantly smaller emissions reductions than originally pledged. Since then, Brazil has updated its NDC, most recently on April 7, 2022, but its new targets would still allow an increase in emissions when compared to the 2016 threshold, according to an analysis by the Brazilian think tank Talanoa.[vi]

At the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow, Brazilian representatives committed to end illegal deforestation by 2028. However, the government has yet to present adequate plans and concrete results towards this goal.[vii] The credibility of this expressed commitment was undermined by the fact—later revealed in the Brazilian press—that the government had delayed the release of official data showing a dramatic increase in deforestation during the previous year, in an apparent attempt to preclude criticism during the summit.[viii]

III. Sabotaging Environmental Law Enforcement

Since taking office in 2019, the Bolsonaro administration has undercut Brazil’s federal environmental agencies, weakening the enforcement of environmental law, removing experienced environmental agents from leadership positions, and publicly deriding the agencies’ work.[ix] The administration’s policies and rhetoric have effectively given a green light to criminal networks that drive the destruction of the forest.[x]

Under the Bolsonaro administration, the number of environmental fines issued by the country’s main environmental enforcement agency dropped dramatically. The average number of infraction notices issued annually for deforestation in the Amazon during Bolsonaro’s first three years in office was 40 percent lower compared to those for the decade before he took office.[xi] Moreover, the average number of fines paid annually in 2019 and 2020 was 93 percent lower than the average number paid annually during the previous five years, a study by researchers at the Federal University of Minas Gerais showed.[xii]

The number of federal environmental enforcement agents, already in decline over the previous decade, has dropped dramatically under the Bolsonaro administration. In May 2020, the federal environmental agency, the Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA), issued a technical note describing the need to hire at least 970 environmental analysts.[xiii] The government announced in 2021 that it would hire hundreds of new staff at its federal environmental agencies. But only 157 of the new hires would be environmental analysts (and only 96 would be assigned to IBAMA), according to a report by Climate Observatory, a leading Brazilian environmental organization.[xiv]

IV. Undermining Protection of Indigenous Lands

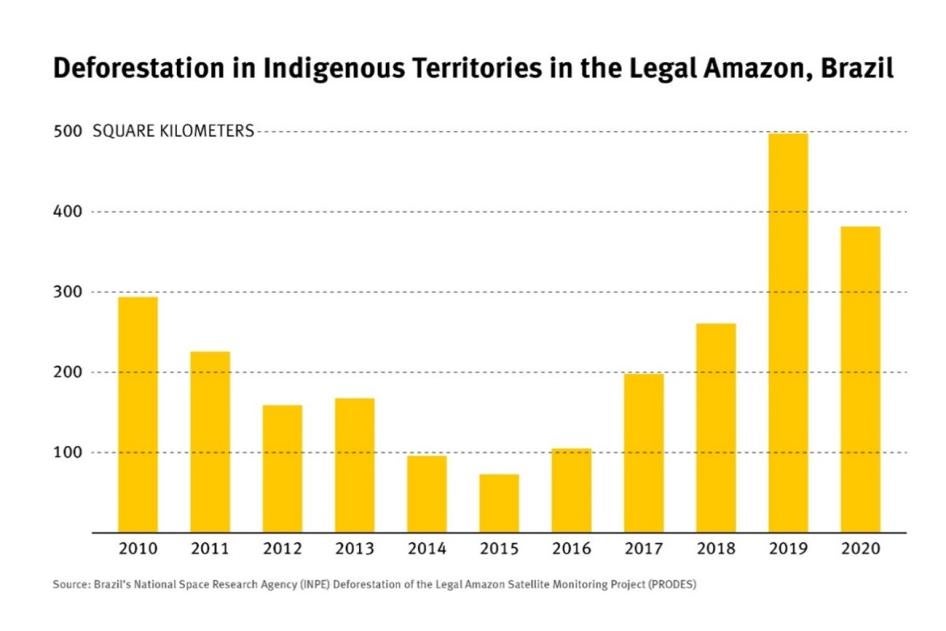

The demarcation and protection of Indigenous territories has been a cornerstone of successful conservation efforts in the Amazon. Deforestation rates on lands securely held by Indigenous peoples tend to be significantly lower than in other comparable areas.[xv] Yet, since President Bolsonaro took office, the federal government has not demarcated any new Indigenous territories, even though the constitution requires it to do so, leaving more than 200 pending demarcation.[xvi]

Instead, Bolsonaro and his allies in Congress have promoted a bill to prevent Indigenous peoples from obtaining legal recognition of their traditional lands if they were not physically present on them on October 5, 1988—when Brazil’s constitution was enacted—or if they had not, by that date, initiated legal proceedings to claim them.[xvii] If approved, the bill would make it impossible for Indigenous peoples who were expelled from their territory before the arbitrary cut-off date or who are otherwise unable to prove they were there or were involved in an ongoing dispute over their claim on that date to have their land rights recognized. The Bolsonaro administration also tabled a bill in Congress to open Indigenous land to mining and other commercial enterprises.[xviii]

Illegal invasions, logging, land grabbing, and other incursions in Indigenous lands increased by 135 percent during Bolsonaro’s first year in office and continued to rise in his second year, according to the Indigenist Missionary Council, a non-profit organization with offices across Brazil.[xix]

V. Violence Against Forest Defenders

The destruction of the Brazilian Amazon is driven largely by criminal networks that employ violence and intimidation against those who seek to protect the rainforest, including against enforcement agents and members of local communities.[xx]

Those responsible for the violence are rarely brought to justice. A 2019 Human Rights Watch report documented how this lack of accountability is largely due to the failure by police to conduct proper investigations into killings and threats, with officials in some locations refusing to even register complaints of threats.[xxi]

Since President Bolsonaro took office, the operations of these violent criminal networks have only become more brazen, according to local prosecutors, human rights defenders, and community leaders.[xxii] The reduced enforcement of environmental laws by the federal government has put local forest defenders at greater risk as criminal networks are reportedly even more emboldened to use violence and intimidation against local residents who oppose their illegal activities.[xxiii]

VI. Contaminated Supply Chains

The accelerating destruction of the Brazilian Amazon is driven largely by the production of agricultural commodities—such as beef, soy, and timber—that are often exported to markets within OECD member states. Despite the existence of various traceability mechanisms, numerous studies have shown that the lack of transparent and effective monitoring of supply chains (including direct and indirect suppliers) makes it impossible to ensure these supply chains are not linked to deforestation or human rights abuses.[xxiv]

___________________________________________________________

[i] National Space Research Agency of Brazil (INPE), “Estimativa de desmatamento por corte raso na Amazônia Legal para 2021 é de 13.235 km2,” November 11, 2021, http://www.obt.inpe.br/OBT/noticias-obt-inpe/estimativa-de-desmatamento-por-corte-raso-na-amazonia-legal-para-2021-e-de-13-235-km2 (accessed April 4, 2022). The figures provided by PRODES cover 12-month periods from August to July and do not include month-to-month tallies. Brazil pledged at the 2009 United Nations Climate Change Conference, known as the Copenhagen Summit, to reduce deforestation in the Amazon region by 80 percent by 2020 compared to average annual deforestation in the region between 1996 and 2005. That average was 19,625 square kilometers, which means that to achieve its pledge, Brazil would have to reduce deforestation to 3,925 square kilometers per year by 2020. Brazil established a National Policy on Climate Change by law in 2009, implemented by Decree 7,390 in 2010, which was replaced by Decree 9,578 in 2018. The decrees incorporated into domestic law the pledge that Brazil made at the Copenhagen Summit. Law 12,187, December 29, 2009, http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2007-2010/2009/lei/l12187.htm (accessed June 30, 2019); Decree 9,578, November 22, 2018, http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2015-2018/2018/Decreto/D9578.htm (accessed January 26, 2021).

[ii] Thomas E. Lovejoy and Carlos Nobre, “Amazon Tipping Point”, Nature, Science Advances 21 Feb 2018:Vol. 4, no. 2, https://advances.sciencemag.org/content/4/2/eaat2340 (accessed January 25, 2021); Thomas E. Lovejoy and Carlos Nobre, “Amazon tipping point: Last chance for action,” Science Advances 20 Dec 2019:Vol. 5, no. 12, https://advances.sciencemag.org/content/5/12/eaba2949 (accessed January 25, 2021).

[iii] Damian Carrington, “Amazon rainforest now emitting more CO2 than it absorbs”, The Guardian, July 14, 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/jul/14/amazon-rainforest-now-emitting-more-co2-than-it-absorbs (accessed April 12, 2022); and Gatti, Luciana V., et al. "Amazonia as a carbon source linked to deforestation and climate change." Nature 595.7867 (2021): 388-393., https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-021-03629-6 (accessed April 12, 2022).

[iv] Human Rights Watch, IPAM, IEPS, “The Air is Unbearable’: Health Impacts of Deforestation-Related Fires in the Brazilian Amazon,” August 2020, https://www.hrw.org/report/2020/08/26/air-unbearable/health-impacts-deforestation-related-fires-brazilian-amazon (accessed April 4, 2022); and Eduardo Geraque, “Invisible enemies: smoke from burnings worsens Covid-19 in the Amazon”, InfoAmazônia, August 23, 2021, https://infoamazonia.org/en/2021/08/23/invisible-enemies-smoke-from-burnings-worsens-covid-19-in-the-amazon/ (accessed April 4, 2022).

[v] Renata Fragoso Potenza et al., “Análise de emissões brasileiras de gases de efeito estufa e suas implicações para metas de clima do Brasil 1970-2020,” Observatório do Clima, 2021, https://www.oc.eco.br/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/OC_03_relatorio_2021_FINAL.pdf (accessed April 4, 2022).

[vi] Natalie Unterstell and Nathália Martins, “NDC: Analysis of the 2022 update submitted by the Government of Brazil”, Política por Inteiro, April 2022, https://www.politicaporinteiro.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Brazils-NDC-2022-analysis_V0.pdf (accessed April 12, 2022).

[vii] Human Rights Watch, “COP26: Don’t Be Fooled by Bolsonaro’s Pledges,” November 2, 2021, https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/11/02/cop26-dont-be-fooled-bolsonaros-pledges (accessed April 14, 2022).

[viii] Débora Alves, “Sources: Brazil withheld deforestation data ’til COP26’s end,” Associated Press, November 19, 2021, https://apnews.com/article/climate-caribbean-environment-brazil-jair-bolsonaro-064dbb71f958ed42aac8ad1c932272fb (accessed April 4, 2022).

[ix] For example, see: Human Rights Watch, “Rainforest Mafias How Violence and Impunity Fuel Deforestation in Brazil’s Amazon,” September 17, 2019, https://www.hrw.org/report/2019/09/17/rainforest-mafias/how-violence-and-impunity-fuel-deforestation-brazils-amazon (accessed March 8, 2022); Human Rights Watch, “Brazil: Amazon Penalties Suspended Since October,” May 20, 2020, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/05/20/brazil-amazon-penalties-suspended-october (accessed March 8, 2022); and Human Rights Watch, “Letter on the Amazon and its Defenders to the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD),” January 27, 2021, https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/02/06/letter-amazon-and-its-defenders-organisation-economic-cooperation-and-development (accessed March 8, 2022); Vinicius Sassine, “Ibama aponta risco de prescrição de 5.000 infrações ambientais lavradas na gestão Bolsonaro,” Folha de São Paulo, March 13, 2022, https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/ambiente/2022/03/ibama-aponta-risco-de-prescricao-de-5000-infracoes-ambientais-lavradas-na-gestao-bolsonaro.shtml (accessed March 15, 2022).

[x] In July 2021, a federal oversight body released an assessment that concluded that public statements from federal authorities, in particular from the President, dismissing the accomplishments of the government’s environmental agencies have harmed the enforcement efforts of the Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA), potentially encouraged deforestation, and coincided with increasing reports of threats and violence against environmental enforcement agents. See: TCU, “Aumento do desmatamento e redução na aplicação de sanções administrativas,” July 23, 2021, https://portal.tcu.gov.br/imprensa/noticias/aumento-do-desmatamento-e-reducao-na-aplicacao-de-sancoes-administrativas.htm (accessed April 12, 2022).

[xi] Observatório do Clima, “The bill has come due - the third year of environmental havoc under Jair Bolsonaro," February 2022, https://www.oc.eco.br/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Relatório-OC.pdf (accessed April 12, 2022).

[xii] Júlia Marques, “Na gestão Bolsonaro, nº de multas pagas por crimes ambientais na Amazônia cai 93%,” Estadão, July 9, 2021, https://sustentabilidade.estadao.com.br/noticias/geral,sob-bolsonaro-n-de-multas-pagas-por-crimes-ambientais-na-amazonia-cai-93,70003782441 (accessed April 11, 2022); and Rajão, Raoni, et al. “Dicotomia da impunidade do desmatamento ilegal.” Policy Brief, June 2021, http://www.lagesa.org/wp-content/uploads/documents/Rajao_Schmitt-et-al_Julgamentos-IBAMA_Dicotomia.pdf (accessed April 11, 2022).

[xiii] IBAMA, "Techinal Note n° 16/2020/CODEP/CGGP/DIPLAN," July 30, 2020, https://piaui.folha.uol.com.br/lupa/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/2020-SEI_IBAMA-7681884-Nota-Tecnica-Concurso.pdf (accessed April 14, 2022) retrieved from “Observatório do Clima, “The bill has come due - the third year of environmental havoc under Jair Bolsonaro," February 2022, https://www.oc.eco.br/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Relatório-OC.pdf (accessed April 12, 2022).

[xiv] Ibid.; and Observatório do Clima, "Governo promete 740 fiscais, mas autoriza concurso para 157," September 6, 2021, https://www.oc.eco.br/governo-promete-740-fiscais-mas-autoriza-concurso-para-157/ (accessed April 12, 2022).

[xv] Kathryn Baragwanath and Ella Bayi. "Collective property rights reduce deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117.34 (2020): 20495-20502, https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1917874117 (accessed April 13, 2022); FAO, FILAC, “Forest Governance by Indigenous and Tribal Peoples: An Opportunity for Climate Action in Latin America and the Caribbean,” FAO, 2021, https://www.fao.org/3/cb2953en/cb2953en.pdf (accessed April 13, 2022); and Helen Ding et al., “Climate Benefits, Tenure Costs: The Economic Case for Securing Indigenous Land rights in the Amazon,” Executive Summary, World Resources Institute, October 2016, Figure 2, p.3., http://www.wri.org/publication/climate-benefits-tenure-costs (accessed June 19, 2019).

[xvi] Daniel Biasetto, “Sob Bolsonaro, Funai e Ministério da Justiça travam demarcação de terras indígenas,” O Globo, January 3, 2021, https://oglobo.globo.com/brasil/sob-bolsonaro-funai-ministerio-da-justica-travam-demarcacao-de-terras-indigenas-24820597 (accessed January 25, 2021); Constitution of the Federative Republic of Brazil, 1988, art. 231, http://www.stf.jus.br/arquivo/cms/legislacaoConstituicao/anexo/brazil_federal_constitution.pdf (accessed June 22, 2019).

[xvii] Human Rights Watch, "Brazil: Reject Anti-Indigenous Rights Bill" August 24, 2021, https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/08/24/brazil-reject-anti-indigenous-rights-bill (accessed April 11, 2022).

[xviii] Maria Laura Canineu and Andrea Carvalho, “Bolsonaro's Plan to Legalize Crimes Against Indigenous Peoples,” UOL Noticias, https://noticias.uol.com.br/politica/ultimas-noticias/2020/03/01/artigo-proposta-de-bolsonaro-para-legalizar-crimes-contra-povos-indigenas.htm (accessed January 25, 2021).

[xix] CIMI, "Amidst the pandemic, invasions of indigenous lands and killings of indigenous peoples increased in 2020," October 28, 2021, https://cimi.org.br/2021/10/amidst-pandemic-invasions-indigenous-lands-killings-indigenous-people-increased-2020/ (accessed April 14, 2022).

[xx] Human Rights Watch, “Rainforest Mafias: How Violence and Impunity Fuel Deforestation in Brazil’s Amazon,” September 17, 2019, https://www.hrw.org/report/2019/09/17/rainforest-mafias/how-violence-and-impunity-fuel-deforestation-brazils-amazon (accessed April 14, 2022).

[xxi] Ibid.

[xxii] Human Rights Watch interviews from October 2021 to April 2022 with prosecutors, representatives of civil society organizations, human rights defenders, and community leaders in Pará, Rondônia and Amazonas states. Names withheld for security reasons.

[xxiii] For example, in the Tapajós basin, an epicenter of illegal gold mining in the Amazon, Munduruku communities that oppose extractive activities in their lands have faced threats and intimidation. In May 2021, people engaged in illegal mining sought to impede an environmental law enforcement operation and set fire to houses belonging to an Indigenous leader and her family. See: Human Rights Watch, "Brazil: Remove Miners from Indigenous Amazon Territory," April 12, 2021, https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/04/12/brazil-remove-miners-indigenous-amazon-territory (accessed April 14, 2022); and Human Rights Watch, "Human Rights Watch statement on attacks against Munduruku indigenous leaders," May 26, 2021, https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/05/26/human-rights-watch-statement-attacks-against-munduruku-indigenous-leaders (accessed April 14, 2022).

[xxiv] For example, see: Raoni Rajão et al., “The rotten apples of Brazil’s agribusiness”, Science Magazine, July 2020, https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aba6646 (accessed April 2022); André Vasconcelos et al., “Illegal deforestation and Brazilian soy exports: the case of Mato Grosso”, Trase, ICV and Imaflora, June 2020, https://cdn.sanity.io/files/n2jhvipv/production/9ba0a2b6ee614a2cf48a196abec067c838448c3f.pdf (accessed April 2022); Amnesty International, “Brazil: From forest to farmland – Cattle illegally grazed in Brazil’s Amazon found in JBS’s supply chain,” July 2020, https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/amr19/2657/2020/en/ (accessed April 2022); Daniel Camargos et al., “JBS mantém compra de gado de desmatadores da Amazônia mesmo após multa de R$ 25 milhões,” Repórter Brasil, July 2019, https://reporterbrasil.org.br/2019/07/jbs-mantem-compra-de-gado-de-desmatadores-da-amazonia-mesmo-apos-multa-de-r-25-mi/ (accessed April 2022); Global Witness, “Beef, Banks and the Brazilian Amazon,” December 2020, https://www.globalwitness.org/en/campaigns/forests/beef-banks-and-brazilian-amazon/ (accessed April 2022); Greenpeace, “The Amazon Silent Crisis – Logging regulation & 5 ways to launder”, May 2014, https://www.greenpeace.org/usa/wp-content/uploads/legacy/Global/usa/planet3/PDFs/Amazon5Ways.pdf (accessed April 2022); Greenpeace, “Greenpeace investigation: EU imports of Amazon timber tainted by widespread fraud in Brazil”, March 2018, https://www.greenpeace.org/eu-unit/issues/nature-food/1170/greenpeace-investigation-eu-imports-of-amazon-timber-tainted-by-widespread-fraud-in-brazil/ (accessed April 2022); Instituto Escolhas, “Raio X do ouro: mais de 200 toneladas podem ser ilegais”, February 2022, https://www.escolhas.org/wp-content/uploads/Ouro-200-toneladas.pdf (accessed April 2022); and Mighty Earth, “Mighty Earth’s new monitoring data reveals deforestation connected to soy trader and meatpackers in Brazil more than doubled over two-year period”, April 2021, https://www.mightyearth.org/2021/04/28/mighty-earths-new-monitoring-data-reveals-deforestation-connected-to-soy-trader-and-meatpackers-in-brazil-more-than-doubled-over-two-year-period/ (accessed April 2022).