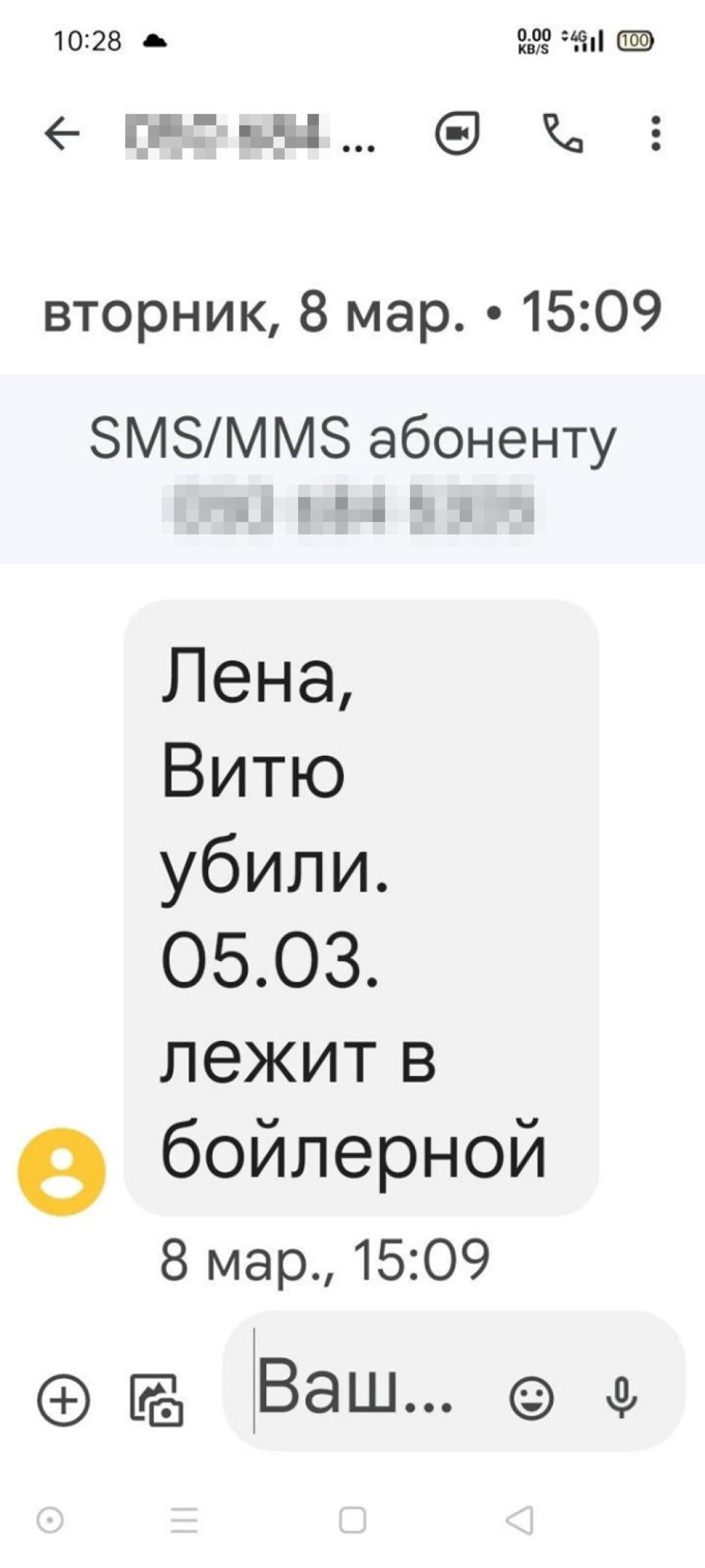

“Vitya has been killed. His body is in the boiler room.”

Olena Koval saw the text message when she turned on her phone on March 8. Her husband Viktor, also called Vitya, was dead.

Olena and her family lived in Bucha, a city of 37,000 roughly 30 kilometers northwest of Kyiv and about 3 kilometers from the military airport in Hostomel. Advancing Russian forces had sought control of Bucha early in the war. The battle for Bucha devastated the city and its inhabitants and Olena, a 43-year-old healthcare lawyer, watched it happen. Relentless shelling trapped people in their homes and shelters. There was no electricity and no gas, which meant no heat in the frigid winter.

Like many in Bucha, Olena kept her phone off to save the battery, only turning it on occasionally to check for texts or calls.

The shelling had eased when Olena received the text message about her husband. She didn’t know how he died, but she knew she needed to try to recover Viktor’s body.

***

For years, Olena, Viktor, 48, and their son, Olexii lived in at Sklozavodska Street 9 in Bucha. When there were celebrations at Maidan Square, in Kyiv’s center, they could see the fireworks from their apartment window.

Because of a spinal disability, walking up and down the stairs had become difficult for Olena. She and Viktor, who was an engineer, bought land nearby and built a two-story house that would be accessible for Olena. They moved into their new home at Vesennya Street 32, in 2019, and planned for Olena’s parents to move in with them.

Everything changed on February 27, when Russian soldiers came to Bucha.

Olena, Viktor, and 24-year-old Olexii were at home. Viktor’s nephew’s wife, Oksana, who was seven and a half months pregnant, was also staying with them.

When the shooting and shelling started, the family, concerned about Oksana, decided to move back into their old apartment because it was right next to an outpatient clinic.

As they left the house, their neighbor, Dmytro Mukhin came by with his family of five, asking for help. The Mukhins didn’t have a bomb shelter and needed a safe place to stay nearby, as Dmytro’s mother walked with difficulty. Viktor offered them the shelter in his backyard and led Mukhin’s family to the house.

Olena, Olexii and Oksana made their way to Sklozavodska Street.

That was the last time Olena saw her husband.

***

Over the next few days, the shooting and shelling became so intense that Bucha residents could no longer leave their houses. “We felt like hostages,” Olena said.

Olena watched the destruction of the city from her apartment window. First, a shell hit the nine-story apartment building at Yablunska Street 17. The building caught fire, and the sixth through ninth floors burned. Then Olena’s parents’ apartment building on Sklozavodska 4 was hit, then building number 6. Olena could also see houses burning in the distance: “There was no water, so no one was putting fires out. Houses just burned, until they burned to the ground.”

Sometimes the shelling died down, but snipers were always around. On March 4, Russian forces hit the water tower and the gas plant[YG1] , leaving Bucha residents without heating, gas, or water.

It was 14 degrees below zero Celsius, with snow on the ground. “We stayed inside, wore layers and layers of clothes to keep warm. We had no water, electricity, practically no phone reception. If there were humanitarian corridors open, we had no way of finding out,” Olena said.

By March 4, Russian forces were everywhere in Bucha. They drove tanks and armored vehicles through people’s fences and parked them in residential backyards. There were military vehicles at every house, near every apartment building. “We saw them [military vehicles] driving down the street [Sklozavodska], shooting randomly at windows,” Olena said. “They were just shooting.”

Russian soldiers went from house to house, breaking doors and windows, searching and questioning people. Olena saw them taking people’s clothes and shoes, changing, and dumping their own clothes on the street.

They heard reports of extrajudicial killings and civilians shot while trying to get water.

Olena had no way of reaching Viktor or the Mukhins. The house was nearby, but going there was too dangerous.

On March 6 the shelling died down long enough for the residents of Sklozavodska Street to step outside for the first time in days. People rushed to break fences, dismantle a children’s playground – anything made of wood to start a fire and cook a hot meal. Some residents went to get water from a nearby well, but there were so many people that after 30 minutes, the water ran out.

On March 8 Olena walked to a spot on a hill outside her apartment building, where she could sometimes get just enough reception to check her messages. When she turned her phone on, the text message with the news about Viktor arrived. She understood her neighbor, Dmytro Mukhin had sent it.

***

Olena didn’t know how her husband died but knew that she had to get his body. She started walking down Sklozavodska Street. She turned on to Yablunska Street. She walked slowly, leaning on her cane. She reached a kindergarten called “Shket”. From there, it was only a few minutes to the house.

A Russian soldier was sitting on the kindergarten’s roof. He told Olena to stop or he would shoot. She said she needed to get her husband’s body and if he wanted to shoot at an unarmed woman with a cane, so be it.

She kept on walking.

“Then I saw our house. One wall was hit with a shell and burned. All the windows were broken, some window frames torn out.” Mukhin’s house was also damaged. “They had a balcony and beautiful French windows, floor-to-ceiling. The balcony was smashed and the windows were gone. Curtains were fluttering in the wind.”

Olena and Viktor’s possessions – bedsheets, plates, pillows – were scattered through the yard.

Two Russian soldiers caught up with Olena as she was about the enter her house. They told her that if she took another step, she would end up lying next to her husband.

“They were very young, 18 or 20. Necks sticking out of the collars.” Olena said. “Really, just kids, not men. But with Kalashnikovs.”

The soldiers walked Olena back to Yablunska Street and told her to stand facing away from her house. One of them shot a gun at her feet, marking a line of bullet holes on the road. “See this line? Walk along it, do not sway,” he told her. “If you veer left or right, you are dead.”

***

Dmytro Mukhin spoke very fast, when I asked what happened to Viktor.

He said that it happened on March 5, at around 1 p.m.

“It was quiet, so we got out of the shelter, [went to the house] and were on the ground floor, in a room. And then [shelling] hit the house, two direct hits, one after another. We all fell to the floor. Two or three minutes later we heard glass breaking outside, then loud steps. Someone was yelling: “Check the second floor!” Vitya moved, he got up, there was automatic gunfire and he fell, screaming in pain. He yelled: “Please don’t shoot! I am wounded, there are civilians here, children, don’t shoot.”

“The [soldiers] started banging on the door. We opened and they walked in. There were 4 or 5 of them, I don’t even remember now. Their clothes were very dirty, some of them had St. George [orange and black striped] ribbons on their helmets. They told us to get outside, one by one. We went into the yard. We said, there is a wounded man there, please help him. They refused. They said they had no bandages or medicines. We stood there for 30 or 40 minutes while they searched the house. Then they came outside, told us to go in and stay there, and left. We went inside. We tried to help Vitya. He was still alive, lying where we left him.

“We cut his sweater open and saw that there was a surface wound on this chest, no entry bullet wound, and I thought for a moment that it was not so bad. But when we turned him over, we saw three bullet holes around his left shoulder blade. His sleeve was soaked through, and the blood pooled on the floor under him. We tried to stop the bleeding with the bedsheet. He was struggling to breathe.”

Viktor died 20 minutes later.

Dmytro and his family put him on a mattress and dragged him to the boiler room, which was the coldest room in the house. They spent two more nights sheltering in Viktor and Olena’s house before fleeing Bucha.

Dmytro’s voice was calm but it shook a little when he said he felt responsible for what happened. “If I hadn’t asked them for help, Vitya might have still been alive.”

***

The next morning Olena, together with her sister, Halyna, attempted again to get Viktor’s body. They got as far as Yablunska Street when they saw a tank on the road. The women stopped and raised their arms. A Russian soldier got out of the tank and yelled at them to turn around and go back. The women returned to the apartment building.

A neighbor told them about a possible evacuation that day. Olena realized that this was likely the last opportunity to get her family out.

The evacuation point was in the city center, five kilometers away. Olena could not walk that far and they didn’t have a car. Olena and her sister stood on the road and waved down passing cars to get rides for her parents, her son, and themselves.

They waited for hours at the evacuation point while Russian soldiers checked people’s phones and rummaged through their things. When they were finally able to leave, Olena said, they drove past her house on Vesennya Street, where their whole family was going to live together, and which was now severely damaged. They drove past abandoned cars, bodies on the side of the road, a volunteer bus riddled with bullet holes, a bicycle on the ground with a man’s body next to it.

Olena still doesn’t know what happened to her husband’s body. Someone told her that he might have been buried in a mass grave. Before she left Bucha, Olena sketched their house on a small piece of paper, marking with a star the room where Viktor’s body was. She left the paper with a neighbor.

“Maybe someone will pass that piece of paper to someone else, who will find him and give him a proper burial,” she said.