On the long road to the border, hundreds of cars and at least a dozen buses with license plates from countries near and far were parked. Most of them belonged to individuals who had traveled there to help transport war refugees to cities all over Europe.

At the end of the road, near what was then known as the Vyšné Nemecké “tent city,” two women in their late 20s or early 30s were pulling suitcases toward a bus with German plates. They quickly tossed their suitcases into the luggage compartment and waited to board.

I introduced myself and struck up a brief conversation. Like most people arriving at the Slovak border, the women, Kate and Yana, were visibly exhausted after a nerve-wracking journey to escape the Russian onslaught. I asked where they’d come from. They said they had just completed a two-day journey from Kyiv, which involved three route changes across more than 800 km. They were on their way to Germany to stay with friends.

Had they seen or heard Russian shelling and bombardments along the way? They’d heard explosions, but were relieved they’d made it safely to Uzhhorod, the Ukrainian border town across from Vyšné Nemecké that was once part of Czechoslovakia. The processing at the border had been quick, they said, and the Slovak border guards friendly. I wished them good luck and said goodbye.

They boarded the bus, which had been organized by Mission Lifeline, a German humanitarian organization that was created to rescue people in the Mediterranean Sea. Now the organization is also arranging convoys of buses for refugees from Ukraine who want to travel to Germany or Austria.

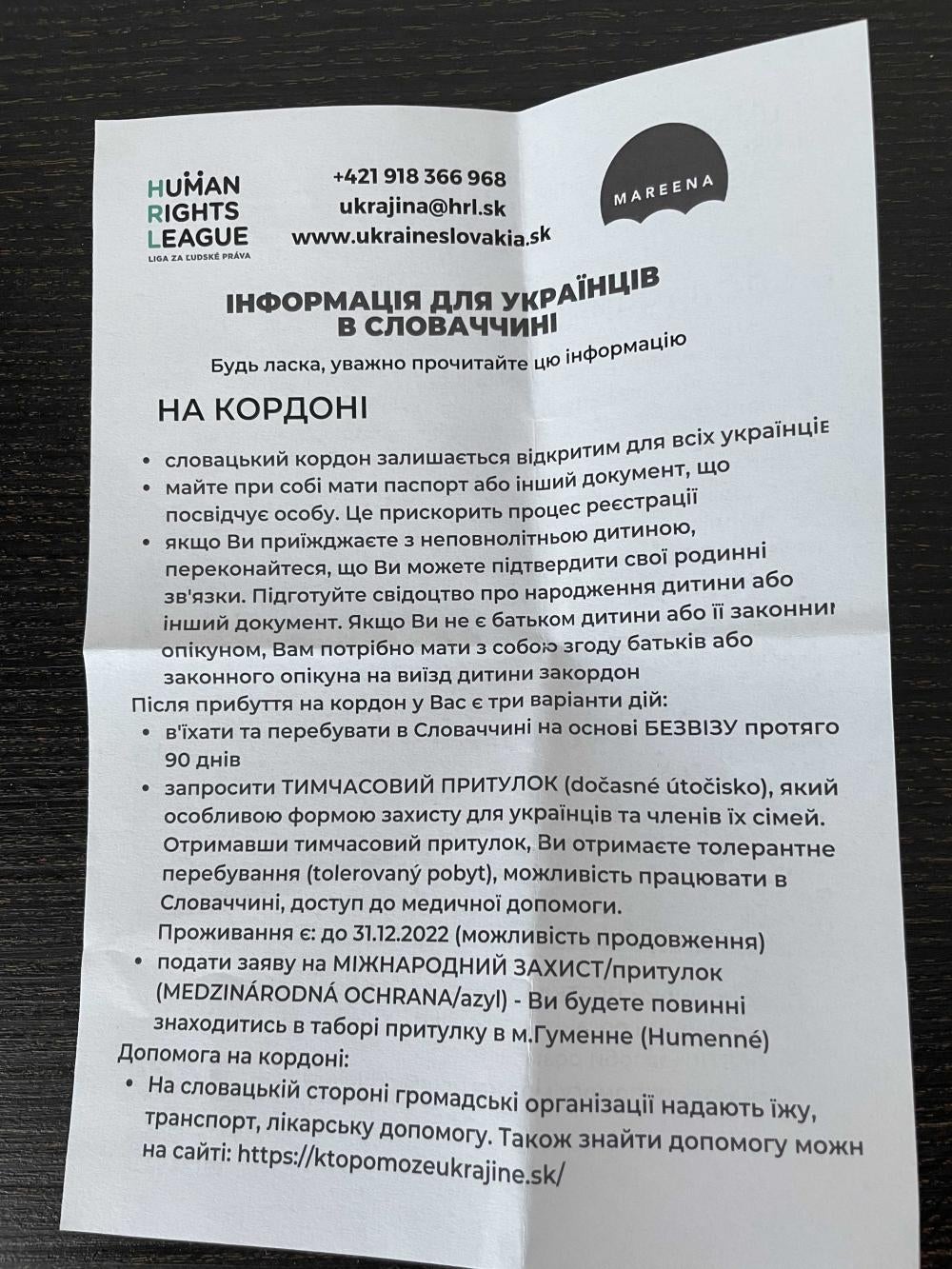

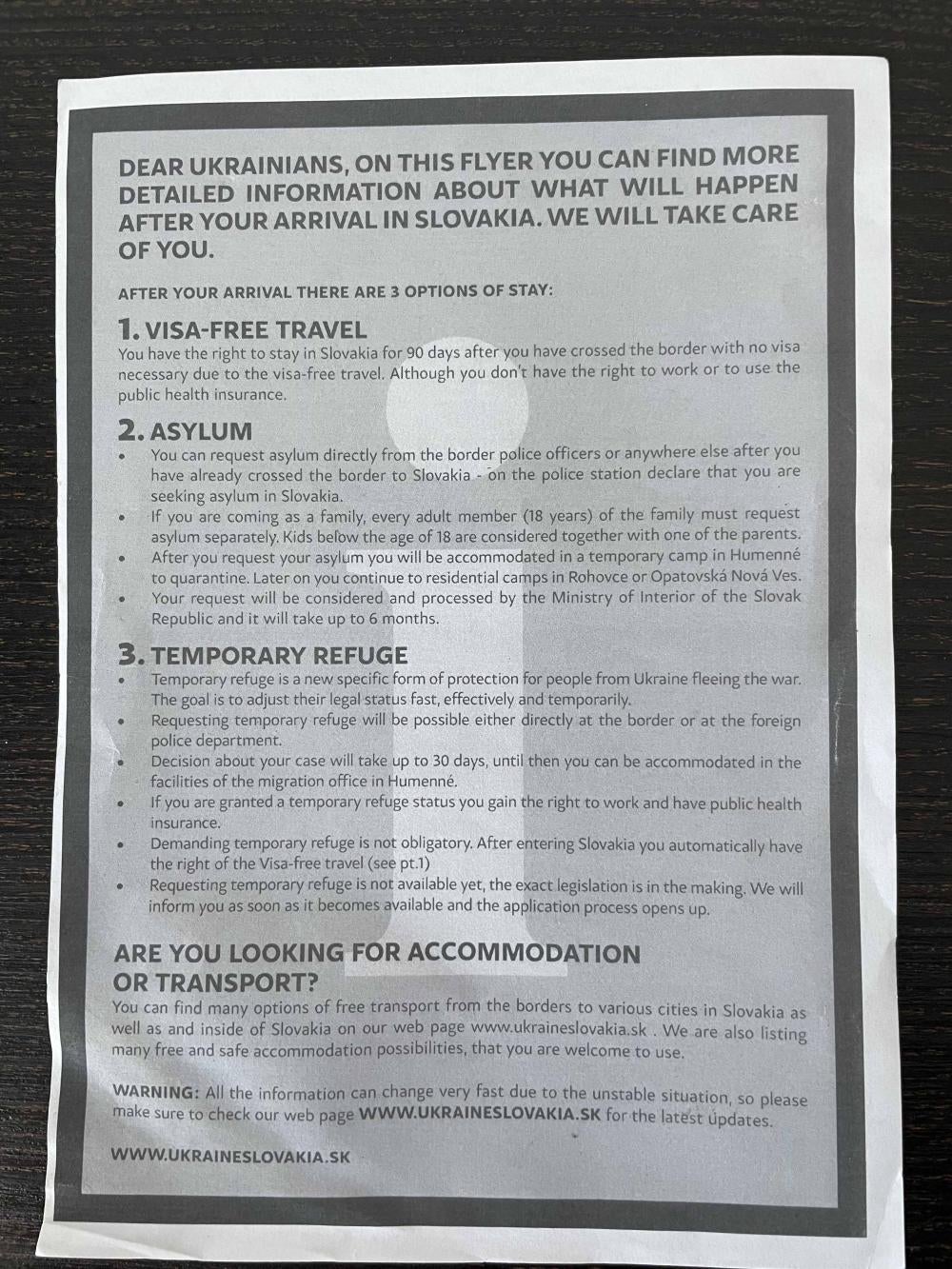

Since the start of the war, more than 3.5 million people have fled Ukraine, most of them to Poland, but hundreds of thousands have come through Slovakia, the vast majority to Vyšné Nemecké. Others have gone to Hungary, Romania, and Moldova. Slovak border and customs police appear to process and register people quickly. Kate, Yana, and others told me it took about 15 minutes to get across the border.

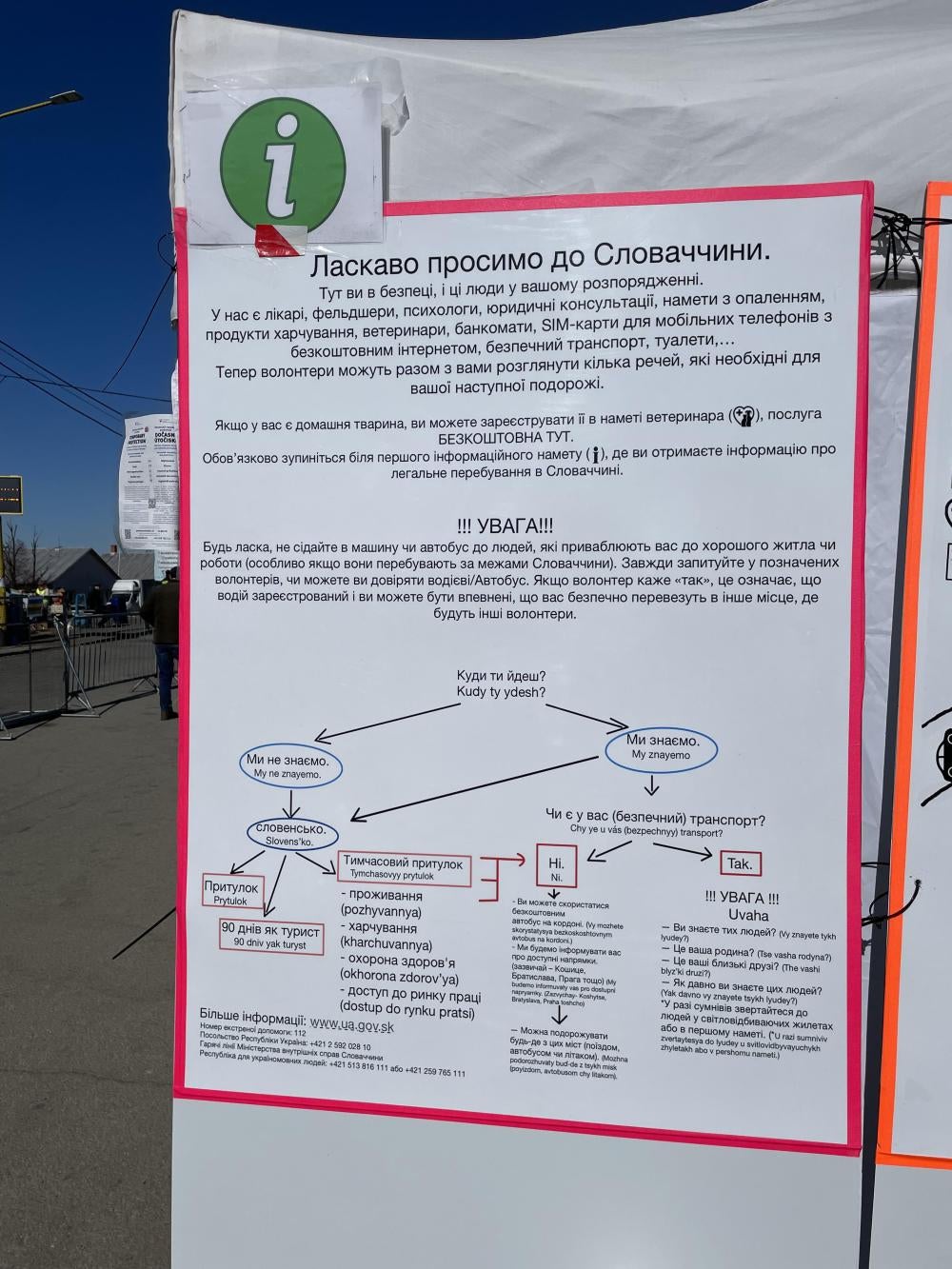

As people streamed across the border from Uzhhorod, they were greeted by a small army of nongovernmental groups with food, water, tea, clothes, diapers, and toiletries; and crucial advice on their legal rights inside the EU. Kate and Yana said they hadn’t needed advice on their rights since they’d found everything on the internet. The aid workers show people where they can eat, wash up, use the toilet, and take a nap in heated tents. There’s a medical truck for people who are ill or injured. There’s even a veterinarian on duty, since many people arrive with dogs and cats. We saw Slovak firefighters and soldiers carrying people’s luggage and pushing wheelchairs with older or injured people or those with disabilities.

Many people arriving from Ukraine, like Kate and Yana, have a clear destination in mind. For the ones who have no idea where they’re headed, aid workers help connect them with temporary accommodations across Slovakia; in hotels, with friends and family, and in private homes.

Once they arrive in Vyšné Nemecké, people want to leave as quickly as possible, a necessity since more people keep arriving. The Slovak chapter of the Order of Malta organizes rides and accommodations for refugees. It’s an operation involving about 10 people at any given time, talking loudly on mobile phones in Slovak, Czech, Ukrainian, Russian, and English, clattering on laptops or shouting into walkie talkies. They take down the names and phone numbers of volunteer drivers, photograph their IDs and car registrations, and then connect them with people headed in directions where the drivers agree to go.

No one appeared to be in overall command in the sprawling tent city of Vyšné Nemecké, but somehow it seemed to be working when we were there, from March 9 to 11. The following week many of the tents and aid group staff were relocated to the town of Michalovce, 30 km away. But a vanguard of aid groups remains at the border to receive people crossing over from Ukraine.

The biggest group there was the Czech humanitarian organization People in Need (Člověk v tísni). But roughly a dozen other groups were working 24/7, including the Bratislava-based group Mareena, the Slovak Red Cross, the Order of Malta, Caritas, Mission Lifeline, and ADRA International. There were a few people with UN-blue vests from the International Organization for Migration and UNHCR, the United Nations refugee agency, but nongovernmental groups seemed to be doing most of the work.

Given EU governments’ often degrading and inhumane treatment of refugees from the Middle East, Africa, and Asia, it was good to see that this outpouring of generosity and solidarity for refugees; it shows what can be achieved when political will and hearts align, and sets a great precedent for the welcome Europe should show to all refugees fleeing war and persecution.

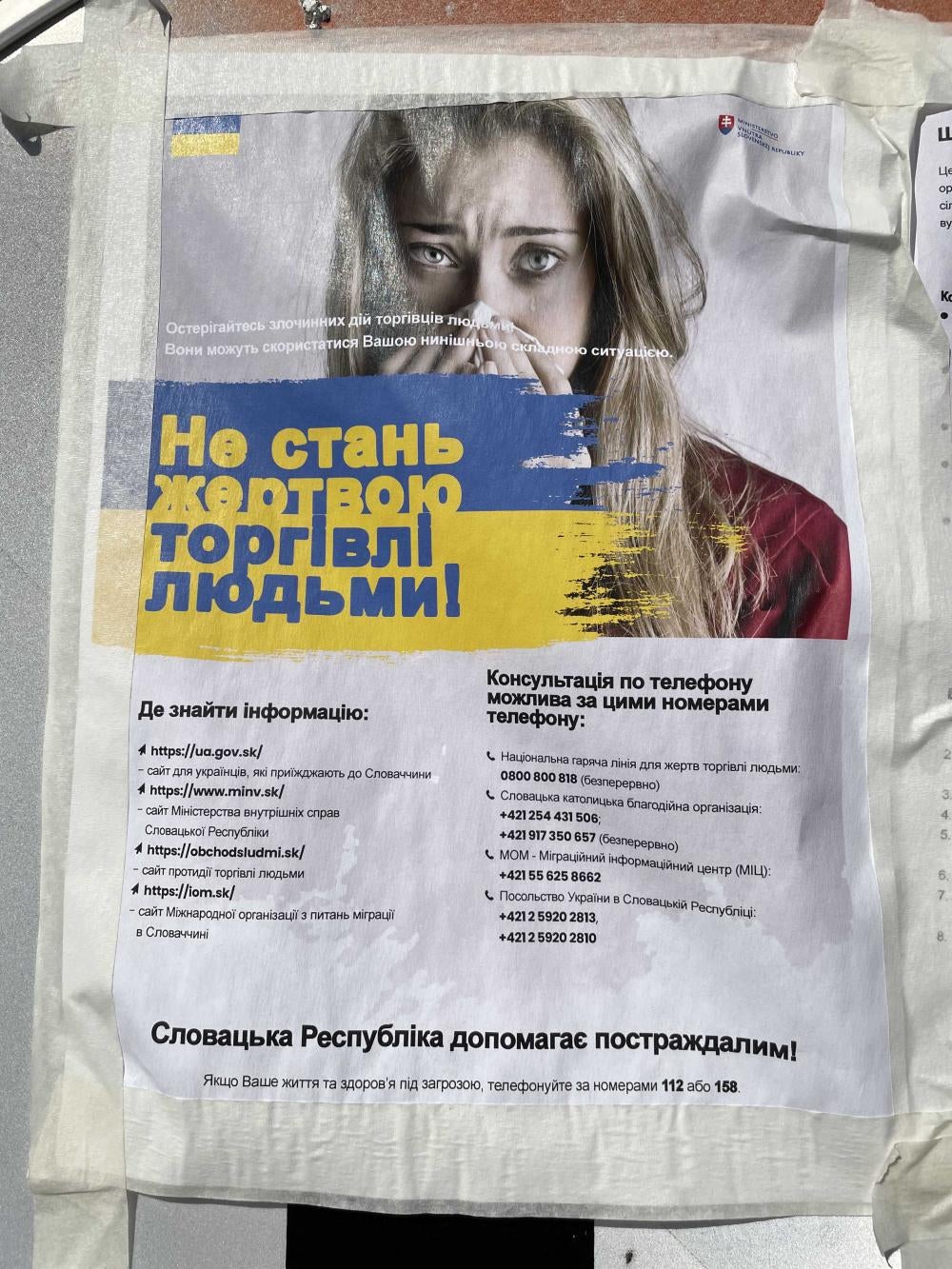

However, in the absence of greater government preparedness and coordination, this organized chaos carries risks. The vast majority of refugees coming out of Ukraine are women and children, including children who made the journey on their own or who have become separated from their caregivers. Virtually every humanitarian and human rights group representative Human Rights Watch spoke with at Vyšné Nemecké voiced concerns about human trafficking.

Those fears intensified on March 9, when a Croatian bus arrived at Vyšné Nemecké. Initially it looked like other buses taking refugees to destinations in Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Germany, Austria, and Italy. But in this case, the bus driver refused to register or give her name. Even more suspicious, the driver said she only wanted to transport women under the age of 30. Several nongovernmental group representatives notified the police, who removed the women from bus.

The organizations working at the border discussed this potential trafficking attempt at one of their twice-daily coordination sessions with the Slovak fire department, police, and military. A decision was made to tighten the driver registration and monitoring process.

Aid group representatives told Human Rights Watch that the new system includes actively warning new arrivals of trafficking risks with signs and leaflets, and calling the drivers and passengers during their journeys to monitor their travel and make sure the refugees are safe. Those arriving from Ukraine are generally reachable since multiple cell phone companies at the border hand out free SIM cards. (Like many of the journalists and humanitarian workers who visit Vyšné Nemecké, my fixer and I registered as volunteers to drive two Ukrainian refugees back with us in our car to Prague.)

The Order of Malta, which organizes most of the transportation at Vyšné Nemecké, are well aware of the trafficking risk and say they’re committed to combat it, as they’ve highlighted on their website. One of the group’s representatives also emphasized their concern when we interviewed him at the border.

Some refugees arriving from Ukraine have been taken advantage of in smaller ways. While transportation out of Vyšné Nemecké is supposed to be free, some drivers have demanded hundreds of euros from their passengers. Now there are signs in Ukrainian making clear to all those who arrive that transportation and temporary accommodations are free.

Non-Ukrainian nationals aren’t eligible for the same protection status in the EU as Ukrainians. Foreign residents of Ukraine continue to arrive every day, albeit in much smaller numbers than at the start of the war. While Ukrainians get temporary refuge across the EU, that’s not the case for most non-Ukrainian nationals. Many need help from their governments to return home, while those who want to apply for asylum or remain in the EU to study or work will have to navigate often confusing rules and options. According to aid workers, most of the foreign nationals who arrived in Slovakia were students from Morocco, India, and Nigeria.

We met three Moroccan embassy officials who were wearing vests with the word “Morocco” on them. They were on the lookout for Moroccan nationals, who would be offered rooms in hotels and flights back home if they wanted them.

It’s not clear what the future holds for the bustling tent cities at Vyšné Nemecké and their new offshoot in nearby Michalovce. In the long-run, authorities at all levels and across the EU need to put in place the infrastructure and programs to provide the support refugees need to secure housing, employment, health care, and education safely. They also need to actively combat the risks of human trafficking by establishing coordinated systems for safe transport and housing with registered – and ideally, vetted – volunteers.

After all, as long as Russia continues to attack Ukrainian cities and towns, the stream of people fleeing Ukraine for safe haven in the EU will likely continue day and night.