The trial was a positive step toward justice for Syrians, but the lack of Arabic translation in the German court shut out many Syrians and others. The language of the court is German, and survivors, witnesses, and others who do not speak German depend on the reporting of those who can physically attend court hearings to follow this momentous case.

True, those participating in the trial and a select group of pre-accredited journalists had access to Arabic translation of the proceedings. But this service was not available for the broader affected community, activists monitoring the trial, and Syrian and other Arabic-speaking journalists reporting on the case.

More than the court sessions were left untranslated. The court news releases never made it into Arabic, and the written verdicts will also only be made available in German.

More trials in Europe involving crimes in Syria are expected, including a trial set to begin in Frankfurt in late January against Alaa M., a Syrian doctor who fled to Germany. The Frankfurt court decided not to provide Arabic translation after the accused in the case waived his right to interpretation, also citing financial considerations.

Court authorities should make Arabic translation more widely available for these cases involving the world’s worst crimes committed abroad. The impact of accountability efforts on affected communities is strongly related to how much outreach is conducted around the case. Prosecutors say Germany is acting on behalf of the international community through the trial in Koblenz. But that would have meant more if information was more accessible to those most affected by the crimes.

As the following stories of Syrians who struggled with the language barrier at the Koblenz trial show, lack of Arabic translation is a missed opportunity; both to increase awareness among Syrians about advancements toward justice and to include them in the process.

Ameenah Sawwan

Ameenah Sawwan boarded a green bus in 2014 without knowing where it was headed, leaving behind her hometown of Moadamiya, in western Damascus. The journey came three years after the uprising began in Syria, followed by government bombings, house raids, and chemical weapons attacks on her town. The Syrian government threatened her family for participating in anti-government protests. Three of her cousins remain missing after the government disappeared them.

“When the world looks at the so-called refugee crisis, they look at us as privileged people who had a choice. They look at us thinking that we had our safety, we had a choice to stay in our homes, but no, we decided to take the risk to escape illegally, to cross borders, to come here,” she told us. “For me, leaving Syria was not a choice.”

Sawwan settled in Berlin in 2016, where she learned German, studied ethics and politics at Bard College, and became a justice and accountability campaigner at the Syria Campaign, a human rights organization that supports Syrians and their struggle for freedom and democracy. In that role, she has closely followed the trial in Germany.

When the trial began in April 2020, two defendants, Eyad A. and Anwar R., were being tried together. Part-way through, the court rendered its verdict against Eyad A., a low-level employee of a notorious Damascus detention center called “Branch 251.” He was convicted of aiding and abetting crimes against humanity in February 2021 and sentenced to four-and-a-half years in prison.

German prosecutors accused Anwar R. of overseeing the torture of detainees at Branch 251. Prosecutors alleged that his subordinates tortured at least 4,000 people during interrogations at the facility, including with beatings and electric shocks. Anwar R. was also charged with 58 counts of murder, as well as rape and aggravated sexual assault.

Sawwan had traveled multiple times to Koblenz with victims’ families to attend the trial.

Despite years of learning German, she found the legal language difficult to follow without Arabic translation. “It was really frustrating,” she said.

Others attending the trial, including Syrian activists and victims’ families, felt the same.

When the court decided to translate Eyad A.’s verdict in February into Arabic, it allowed her to more fully understand and process its significance, which she said made a “huge difference.”

As she heard the verdict spoken in Arabic, she came to see the trial as a symbol of justice for all Syrians who have suffered abuse and loss, even though it fell short of full accountability.

“I listened to what the judge said on the day of the verdict of Eyad A. and she listed loads of crimes and violations between 2011 and 2012 only. And it took her like three hours,” she said. “And I wonder, what could we list in the last 10 years then?”

Hassan Kansou

Hassan Kansou was born in Damascus but spent most of his life outside Syria. He was in Egypt studying medicine when protests spread across the Middle East in 2011. As civilian casualties in Syria mounted, he felt called to act. He became a data analyst for the Syria Justice and Accountability Centre (SJAC), working to verify documents and videos of alleged crimes committed in Syria, identify those responsible, and use them toward future accountability.

He went to Turkey to study medicine but was worried about rumors that the government there planned to send Syrians back to Syria. He decided to go to Europe and ended up in Germany. Through daily language courses over months, he learned German and was asked by SJAC to monitor the Koblenz trial.

When witnesses spoke in Arabic, he understood, but he often had to turn to others to help him piece together complicated legal arguments in German. Arabic translation was only provided by headset to the accused, other parties to the case, witnesses, and to a few pre-accredited journalists. Officials denied Kansou’s request for headsets to access the translation.

Alongside the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights, Kansou filed a petition with the German Constitutional Court to ask that Arabic interpretation be made available for those in the public gallery. Though the court issued a temporary order extending translation to pre-accredited Arabic-language journalists in response to the petition, the trial remained inaccessible to non-German speakers in the public gallery, including Kansou. Kansou felt the move excluded those who could be most impacted by the trial.

“I appreciate the work that the court is doing, and the trial is doing so much that I want everybody to know about it,” he said. “That’s the only thing I want. So why couldn’t we deliver that in a more accurate way?”

Kansou recognizes the trial’s limited scope but sees it as an important step others in the Syrian community should know about so it can feed into accountability, which he sees as critical to Syria’s fate.

“I don’t know what’s the difference between old Syria and future Syria if there is not justice in it,” he said.

Moner Alkadri

Moner Alkadri traveled by train, four hours each way, to attend the trial in Koblenz in memory of his friends, Mohammed and Momen. Arrested together in 2014 for attending protests in Syria, he was the only one to survive after three months in Damascus prisons. He and his wife arrived in Germany in 2015 with their cat, the only possession that wasn’t stolen along the way.

Memories of growing up in Syria have been replaced with thoughts of his friends in prison. So, he came to watch the trial and look into the eyes of the accused.

“The court will not return the missing, but it does restore hope to their families, that those who caused their pain will be tried today for their crimes,” he said.

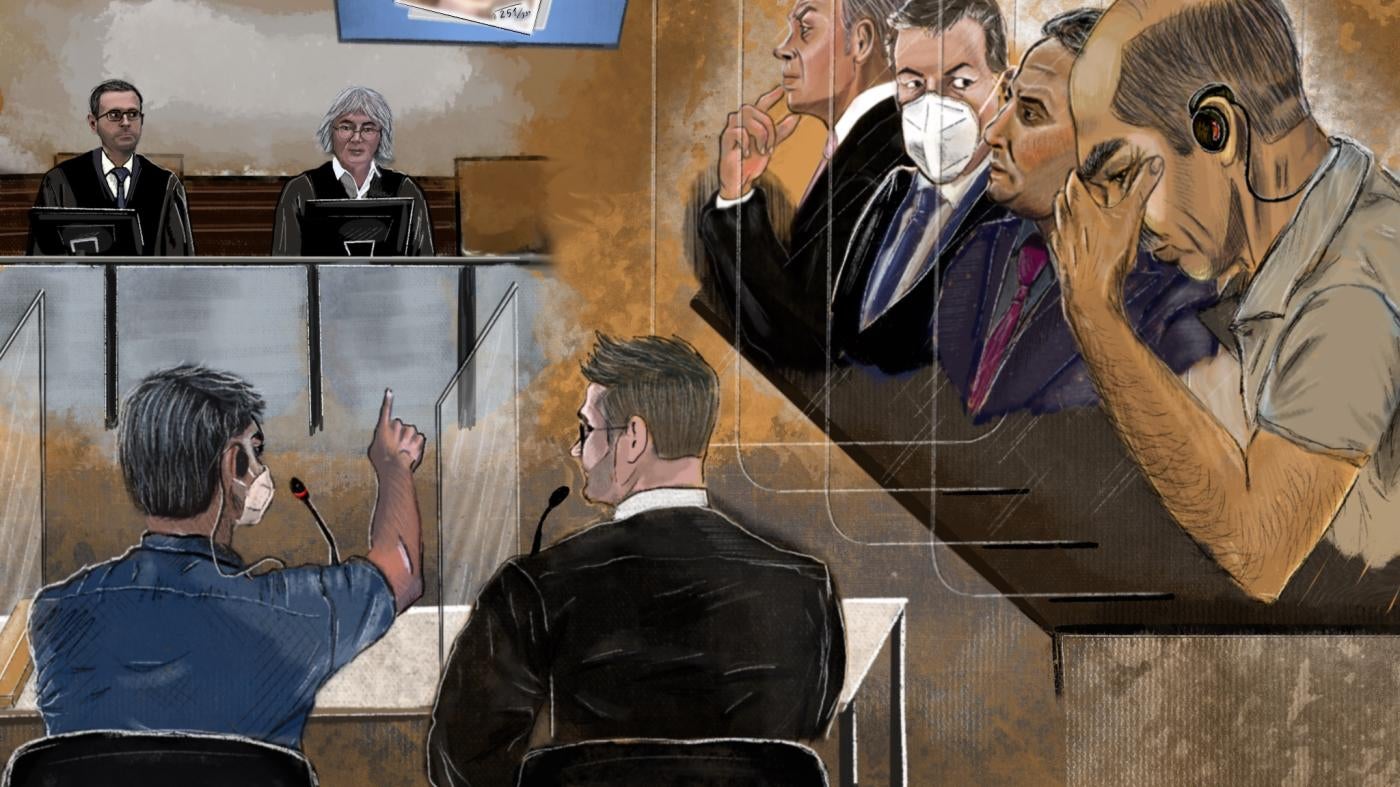

He has followed the trial from the beginning, even though he hasn’t made it to court every day. He plans to study animation at a college and was commissioned by Human Rights Watch to do some illustrations of the trial.

He can understand a lot of what people are saying during the trial, and when the witnesses speak in Arabic, he recognizes his own experience in their testimony. Although he can speak and understand German, he has seen people get frustrated when they come to the trial and can’t understand, especially families whose children have been missing for years in Syria’s prisons.

He said having Arabic translation more easily available would encourage other Syrians to come and could provide a glimpse of justice and a reminder that the world has not forgotten them. For the families, and for him, these kinds of trials can provide reassurance that the lives of those tortured, killed, or disappeared matter.

“It’s very important to the families to feel like there’s someone caring,” he said.