(Washington, DC) – The El Salvador authorities, including President Nayib Bukele, are blocking people on social media who criticize the government, Human Rights Watch said today. This violates their rights to free speech and access to information, and to participate in the conduct of public affairs.

Human Rights Watch identified 91 blocked accounts, the vast majority on Twitter, including accounts belonging to journalists, lawyers, activists, and private citizens. President Bukele blocked most of them. Government institutions, including the President’s Office, the President’s Press Office and the Communications Secretary’s Office have also blocked some accounts. The total number of blocked accounts is most likely higher. Blocking users on social media appears to be a part of a broader effort by the Bukele government to silence critics and hinder transparency.

“President Bukele uses social media as a key means to conduct government business and communicate with the public, to such a degree that his Twitter account has virtually become El Salvador’s Official Gazette,” said Juan Pappier, senior Americas researcher at Human Rights Watch. “By blocking people he disagrees with, Bukele is denying them access to public information and limiting their ability to engage with the officials who represent them.”

Blocked people need to log out of their social media accounts to see posts by President Bukele and others, making it harder to access government information. They cannot interact with the posts, such as to repost, respond, like, or comment on them. This prevents blocked people from participating in public debate, violates their free speech rights, and, when it occurs in response to criticism, discriminates against them on the basis of their opinions, Human Rights Watch said. Blocked journalists cannot ask questions or request information, infringing on freedom of the press.

On October 8, 2021, Human Rights Watch requested information from the President’s Office concerning the number of people blocked on Twitter and Facebook by President Bukele, Vice President Félix Ulloa, and institutional accounts of the President’s Office, the President’s Press Office, and the Communications Secretary’s Office. Human Rights Watch has not received a response.

Blocking social media accounts is of particular concern in a context in which the government has hindered access to public information and targeted independent rights groups and journalists, Human Rights Watch said.

The Bukele administration has weakened the role of the Access to Public Information Agency (IAIP) – charged with ensuring compliance with the Access to Public Information Law – by reforming the implementing regulations for the Access to Public Information Law in ways that undermine the agency’s autonomy and by firing a commissioner who had been critical of the government’s lack of transparency.

In November, Bukele introduced a “Foreign Agents” bill in the Legislative Assembly to regulate the work of civil society groups that receive foreign funding. If passed, the bill would severely restrict the work of independent journalists and human rights groups. The bill’s introduction comes on the heels of a series of measures to intimidate and harass civil society groups, including creating a legislative commission to investigate the allocation of funds to nongovernmental groups, the creation of a legislative commission to investigate the allocation of public funds to NGOs, several raids of nongovernmental organization offices that appear to be politically motivated, and seemingly arbitrary investigations against independent media outlets.

Senior government officials, including President Bukele, and official institutions should not block people from social media accounts used to share information of public interest or to discuss public affairs, Human Rights Watch said.

President Bukele regularly conducts official business through his Twitter account. He has used social media to announce that officials have been fired, advocate the adoption of legislation, communicate Covid-19 regulations, and announce the distribution of government-funded aid. He has also used his account to lash out against judges, nongovernmental institutions, and the independent media, and to comment on the bilateral relationship between El Salvador and other countries.

President Bukele also interacts with comments by constituents on issues ranging from bitcoin to local investment.

President Bukele’s Twitter account has over 3 million followers.

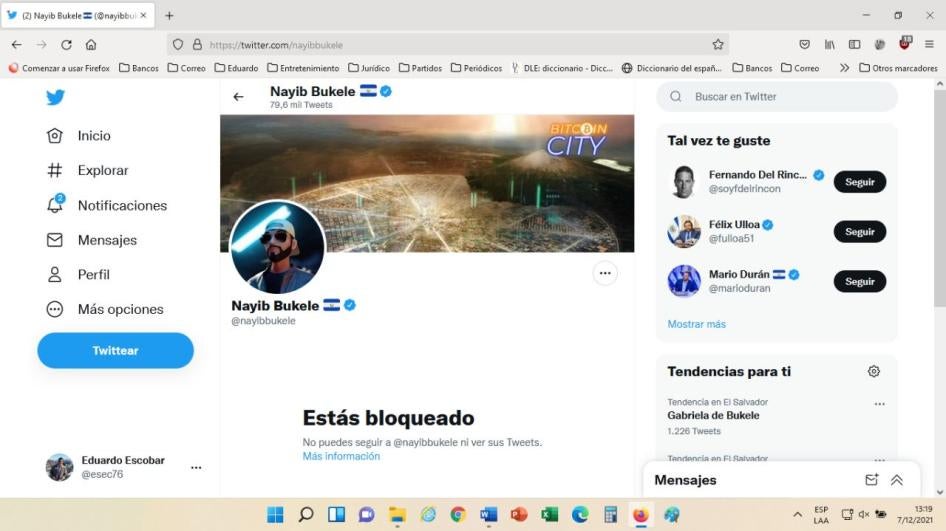

In September, Human Rights Watch posted messages on Twitter asking users to send screenshots if President Bukele or other senior government officials had blocked them. Eighty-one people provided screenshots that showed their username, which identifies an account, and a message saying they had been blocked by President Bukele’s or other senior government officials’ accounts.

Human Rights Watch reviewed each screenshot and found no signs that they had been maliciously altered. At the time they were reviewed, none of these 81 accounts were actively following President Bukele’s Twitter account or the account of government institutions and other senior government officials they had stated they were blocked by, which is consistent with their allegations that their account had been blocked. Most of the individuals who sent screenshots said they were blocked after publishing comments criticizing the government.

Human Rights Watch also searched Twitter using keywords to identify other blocked accounts and found another 10 people, most of them journalists, who posted on Twitter that President Bukele or government institutional accounts had blocked them. None of these accounts were actively following President Bukele or the government institutional accounts mentioned, which is consistent with the other blocked accounts.

In 2019, an administrative court in El Salvador issued a ruling in a case involving the Ombudsperson’s Office Twitter account. The court said that, by blocking a user, the Ombudsperson’s Office “had denied the person the possibility of accessing and receiving public information shared through the institutional account,” and ordered the user unblocked.

Courts in other countries have ruled that public officials cannot block people from social media accounts they use for official business just because they express an opinion the official dislikes. In the United States, an appeals court ruled in 2019 in a case involving then-President Donald Trump that the first amendment of the US Constitution, which upholds free speech, “does not permit a public official who utilizes a social media account for all manner of official purposes to exclude persons from an otherwise‐open online dialogue because they expressed views with which the official disagrees.”

In a case filed by a reporter, Mexico’s Supreme Court ruled in 2019 that the Attorney General of the state of Veracruz was using his Twitter account to provide information about his work as a public servant, and thus it should be available “to all constituents,” particularly to journalists, who should have greater protections for their ability to access information of public interest.

Under international human rights law, governments are obligated to protect freedom of expression, including the right to seek, receive, and impart information of all kinds online and offline; as well as people’s right to take part in the conduct of public affairs, including by engaging in discussions about matters of public interest.

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and other treaties to which El Salvador is a party permit restrictions on freedom of expression only if they are provided for by law and are strictly necessary and proportionate to achieve a legitimate aim, including the protection of the rights and reputations of others or the protection of national security, public order or public health and morals, and are nondiscriminatory. The ICCPR and the American Convention on Human Rights prohibit discrimination on the grounds of political or other opinion. Both the UN General Assembly and the Human Rights Council have stated that the same rights that people have offline, particularly freedom of expression, must also be protected online.

In addition, the Declaration of Principles on Freedom of Expression, adopted by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights in 2000, states that “public officials are subject to greater scrutiny by society.”

Based on these standards, senior public officials like President Bukele and his cabinet members should only be able to delete comments by social media followers or block them under very limited and narrowly defined circumstances, which should be provided for in law. Such circumstances would include situations in which restrictions are necessary to protect a person’s rights to nondiscrimination or personal security, such as when the content or behavior constitutes sexual harassment or incitement to violence, or when users publish private, personally identifiable information about a person with malicious intent.