What is the report about?

One of the most important developments for women in Afghanistan as part of the post-2001 reconstruction effort was the 2009 Elimination of Violence Against Women (EVAW) Law, created to provide women and girls with legal protection from domestic violence.

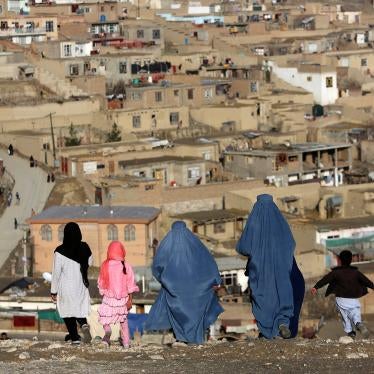

The report shows the obstacles Afghan women face as they attempt to pursue justice through the courts. Although families and police frequently deter women from registering complaints, the law has driven slow but genuine change for Afghan women.

Unfortunately, the law has not been fully implemented, but in a country like Afghanistan, where patriarchy has such deep roots, even having this law has been a huge achievement. It’s so important that the law is preserved.

Another victory for women was the 2004 constitution, which included for the first time in Afghanistan’s history a provision – article 22 – that men and women were equal, and there could be no discrimination on that basis. Up until then, my mother had never even been able to get a national identity card because women were not allowed to. Only my father could.

But now people fear that laws like EVAW and other advances in women’s rights will be in danger as the Taliban gain more power.

How can Afghanistan’s government focus on this law when the Taliban is on their doorstep?

The Afghan government claims to be protecting the gains achieved since 2001. They specifically say progress in women’s rights is one of those gains. But they have already failed to fully implement the EVAW Law. There are many people in the government who do not fully accept women’s rights.

Yes, if the Taliban gain more power it is going to get harder. But now there is more legal infrastructure, many more educated women lawyers, and others who have been leading this fight. They are not going to stop, and they deserve support. This is not the time to walk away.

Why was the EVAW Law never fully implemented?

Many members of parliament – men with very conservative mindsets – have opposed it, and so the law was issued by decree rather than going through parliament. The rules of men have defined Afghan society for a long time and this law is a challenge to that. Also, there is a lack of awareness among many women who don’t know they have rights and don’t know about the law. Others who may want to seek justice simply cannot afford to travel and take the time to report cases and see them through the justice system. And most women are financially dependent on their male relatives, so they can’t afford to file a complaint against someone on whom they depend for their very food and shelter.

Also, there is a huge stigma about reporting domestic violence. There is a strong belief that such issues should not be brought up outside the home. And, of course, many do not trust the justice system. They see it as corrupt or lacking capacity and they don’t trust the police. And the police themselves do not understand or accept the law.

How did you research this report in Afghanistan?

It wasn’t easy. From finding women who would tell their stories to government officials who would be willing to talk to me, it was hard. Most of the women and girls were at shelters, so I had to get permission from the Ministry of Women’s Affairs, or through their lawyers. And I wanted to talk to women from different parts of the country, so that meant traveling to four different provinces. I could only go to cities, where the shelters are. It was not safe to travel into some areas.

Also, I had to keep the women I spoke with safe, making sure they would not be identified because of possible retaliation from their families. As we say in the report, Afghan women and girls are at risk for so-called honor killings by their families, and these cases are almost never prosecuted.

Did any stories of the women you spoke to stand out to you?

Yes, there was a girl at a shelter in Bamiyan who was only 17. She had been raped by a boy from a prominent family – he tricked her into meeting him – and then when she went to the police and filed a complaint against him, he bribed his way out of facing any charges. She, on the other hand, was prosecuted for having sex outside of marriage which is illegal in Afghanistan. It was so unfair. She had become pregnant and was giving up her baby for adoption. She was so sad, I remember her eyes when she said to me, “I don’t know if I should love my child or not.” She knew she would never be able to go back to her home; her relatives had sworn to kill her. I don’t know what happened to her when she finally was released. I kept thinking about her for months.

What more should the Afghan government do to ensure police respond as they should to domestic violence complaints?

There should be more focus on training the police and family response units to handle cases properly, especially rape cases. There should be better monitoring of cases as they move through the system, making sure the cases don’t get lost and that police register cases properly. A way to track cases is essential to hold the police accountable.

Donors are essential for funding this type of police training. But right now, countries may be afraid to fund such projects as the Taliban gains ground. What would you say to this?

Some donors say now that “it was never going to turn out in Afghanistan, it was never going to be possible to bring change.” But the support for women’s rights has worked. There has been notable progress, such as a significant decline in maternal mortality, and much-improved access to key health services such as prenatal care and contraception. There are more women judges, prosecutors, and legal aid workers, and women have taken on other roles in public life. International funding also helped expand education for girls. There is much more to do, but this progress must be expanded and protected. Continued engagement and funding matter. There are still organizations and activists on the ground who will continue working, and they will undoubtedly need the support of the international community.

*This interview has been edited and condensed.