Summary

The international reconstruction effort in Afghanistan after 2001 created an opportunity to advance human rights, and women’s and girls’ rights in particular. Although its achievements have fallen short of what was envisioned, significant improvements in legal protections have emerged through the adoption of new and revised laws, the founding and growth of legal aid organizations, and the training of a cadre of women lawyers, prosecutors, and judges.

In addition, efforts by nongovernmental organizations and some governmental bodies to support legal aid and implement reforms have had significant impact in increasing access to justice for women, notably the 2009 Elimination of Violence against Women (EVAW) law.

More than a decade after it came into effect, EVAW has helped facilitate a rise in both reporting and investigations of violent crimes against women and girls, and, to a lesser extent, convictions of those responsible. With the support and funding of international donors, the Afghan government established specialized police units called “Family Response Units,” prosecution offices, and special courts with female judges to carry out the EVAW law. Particularly in urban areas, women have seen growing awareness of the law and improvements in the way judicial institutions respond to EVAW cases.

But as the opposition armed group, the Taliban, have made territorial gains, the prospect of a Taliban-dominated government or descent into fragmented civil war threatens the existing constitutional order, including provisions guaranteeing women’s equality and the EVAW law.

This report is being released as the United States and other countries complete their troop withdrawals from Afghanistan, leaving uncertain the survival of the post-2001 Afghan state. In light of this, it is vital that Afghanistan’s international partners continue to support efforts to protect women and girls from violence and hold perpetrators to account.

The EVAW law, decreed by then-President Hamid Karzai in 2009 and reconfirmed by President Ashraf Ghani in 2018, makes 22 acts of abuse toward women criminal offenses, including rape, battery, forced marriage, preventing women from acquiring property, and prohibiting a woman or girl from going to school or work. The law has encountered considerable resistance from conservatives inside the Afghan judiciary and parliament but has also driven slow but genuine change and has become an advocacy lynchpin for the efforts of Afghan women’s rights groups to reform other laws.

Despite the gains since 2009, full implementation of the EVAW law remains elusive, with all actors involved—including police, prosecutors, and judges—often deterring women from filing complaints and pressing them to seek meditation within their family instead. Family pressure, financial dependence, stigma associated with filing a complaint, and fear of reprisals, including losing their children, have also deterred women from registering cases.

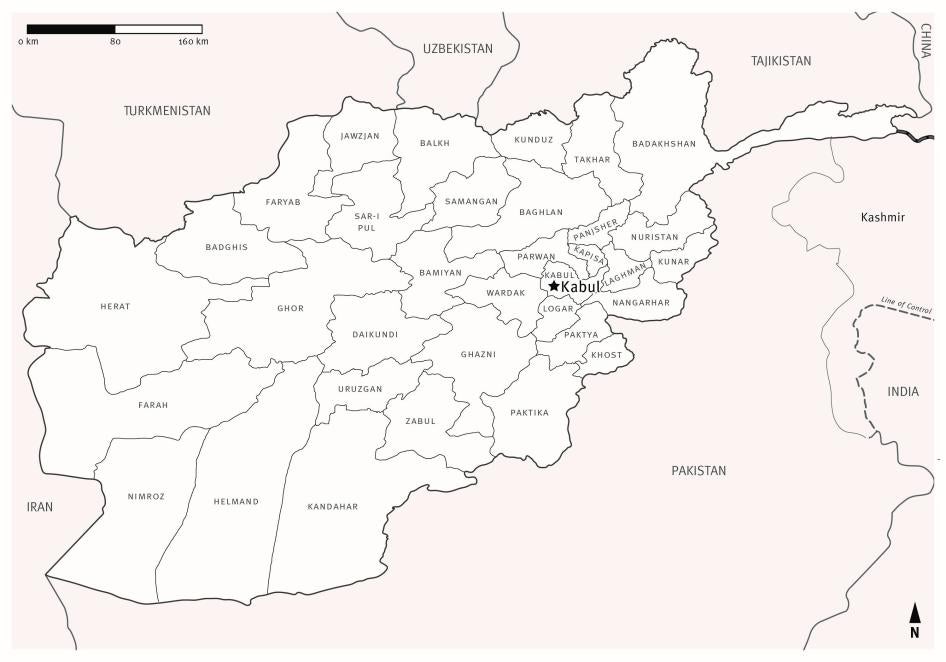

This report focuses on the experiences of Afghan women in their attempts to pursue justice through the EVAW process. It is based on 61 interviews between 2018 and 2021. We interviewed women and girls who had reported crimes that fell under the EVAW provisions, either directly to the police or to designated EVAW prosecution units in Kabul, Herat, Mazar-e Sharif, and Bamiyan. We also interviewed prosecutors involved in EVAW cases, judges from the special EVAW units, lawyers, legal aid providers, healthcare workers, and staff from nongovernmental organizations and other advocacy groups who have been involved in EVAW investigations, training, and reforms.

From the moment an Afghan woman decides to file a complaint under the EVAW law, she faces resistance. If she files the complaint with the police, they are supposed to either take the complaint or refer her to the nearest EVAW investigation unit. However, in many cases involving violence from a male family member—often the husband—police discourage women from filing a case and pressure her to go home and reconcile.

Even if she manages to file a case, pressure or threats from relatives frequently compels women to withdraw cases before or after they reach the investigation stage. In most of these cases, the women do not have access to lawyers. Because the EVAW law provides that prosecution of most crimes must be based on a complaint that the victim, her family, or her attorney files, the case cannot proceed and is dropped if a complaint is withdrawn.

Although mediation is often dangerous for women who are put at risk by being convinced to reconcile with their abuser, EVAW cases are commonly resolved through family mediation—often traditional informal councils, or jirgas. The EVAW law prohibits mediation in only five kinds of offenses against women: rape, forced sale of sex, publicizing the identity of a victim, burning or the use of chemical substances to cause harm, and forced self-immolation or suicide. For these offenses, even if the woman (or family member in the case of death) does not file a complaint, or tries to withdraw it, the state is obligated to prosecute. In all other cases, police and other officials can pressure the woman to have her case resolved through mediation.

In violation of the law, EVAW officials have sometimes referred cases to mediation when it is prohibited. Particularly outside major cities, officials often refer women and their relatives to traditional councils to resolve cases, including violent crimes, thereby bypassing the justice system altogether. This kind of mediation often leads to outcomes that deny women protection and justice and reinforces impunity, even for the most serious crimes.

Failure by police to arrest suspects is one of the most common reasons that cases do not progress. Police are particularly reluctant to arrest husbands accused of violence against their wives. Although conviction rates for murdering women have risen, this is not the case for so-called “honor killings,” when women and girls are killed by family members. While the revised 2018 penal code stipulates that “honor” is not a defense in a murder case, “honor killings” remain widespread. Particularly in rural areas, judicial authorities often condone them.

As cases move forward, complainants face additional obstacles. Lawyers told Human Rights Watch that, while awareness of the EVAW law has improved in recent years, police and prosecutors in many parts of Afghanistan still lack knowledge of the law or deliberately ignore it. One lawyer described the case of a woman who filed a complaint against her husband with the police and was later told it had been “lost” and never referred for investigation. There is no system in place to prevent police from interfering, or even removing, files. With competent legal counsel, some women have seen their violent husbands convicted and imprisoned, and sometimes also received monetary restitution—but these cases are the exception.

Throughout the process, women face additional risks of abuse. The EVAW law does not address so-called moral crimes under Sharia, Islamic law, under which most women and girls are prosecuted. Although the Afghan Supreme Court ruled in 2017 that “running away” from home was not a crime, women and girls who leave their homes—often fleeing domestic violence—are frequently charged with and prosecuted for moral crimes such as “attempted zina”—attempting to engage in sex outside marriage.

Many women and girls who report violent crimes committed against them, including but not limited to sexual assault, describe being subjected to invasive and abusive vaginal and sometimes anal examinations for the purpose of determining virginity. Such “virginity tests” have no medical basis and the World Health Organization has stated that healthcare workers should never conduct examinations for this purpose. In Afghanistan, government doctors, frequently men, conduct these examinations, often without consent. They are not limited to rape cases, and often do not focus on whether forced intercourse had taken place. Reported “findings” are often accepted as evidence in court, contributing sometimes to long prison sentences for women and girls. Although Afghan human rights groups and some Afghan officials have advocated for an end to these “virginity tests,” their use remains widespread.

Despite its limitations and weak implementation, the EVAW law represents a landmark legislative tool for combatting discriminatory and violent offenses against women and girls in Afghanistan. That it has withstood opposition from conservative detractors in parliament is a testament of shifting attitudes. Among some jurists, the EVAW law has given other progressive laws, like the anti-harassment law, a foothold and has begun to change perceptions about the need to address violence in the home and in larger Afghan society.

In areas under Taliban control, their courts also hear a small number of domestic violence cases, but they generally defer to local customs and pressure the parties to resolve such disputes at home. This approach mirrors the deficiencies of government courts that press women to pursue mediation within the family rather than prosecution, but without the option for criminal prosecution that the EVAW law provides.

With donor funding and interest in Afghanistan declining in tandem with the withdrawal of foreign troops from Afghanistan in 2021, women’s rights organizations and other civil society groups have raised concerns that there will be less international support for the advocacy and training needed to protect and strengthen implementation of the law.

Growing Taliban influence and control, and the possibility that a coalition government might emerge to avert a return to a fragmented civil war as occurred in the 1990s, has heightened fears that legislation like the EVAW law will be in danger as the Taliban and conservative pro-government politicians gain more power.

Afghanistan is on the brink of another transition; preserving the gains of the EVAW law and access to justice for women will be a critical test.

In July 2021 we provided Afghan government officials with a summary of our findings. On July 28, 2021, the Attorney General’s Office of Afghanistan provided a statement saying that it had not found any irregularities in the processing of EVAW cases but would raise our concerns in the government’s High Council on Violence against Women. It concurred that continued support from Afghanistan’s donors will be vital to preserving legal protections for women’s rights. (See Appendix.)

Key Recommendations

To the United Nations, United States, United Kingdom, European Union, and other Donors

- Advocate forcefully that all parties preserve rights protections, as provided for in the 2004 constitution and laws of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, including the Elimination of Violence against Women (EVAW) law;

- Continue support to initiatives aimed at enforcement of the EVAW law, including training for professional staff and technical assistance and support for provincial prosecution offices and courts; and

- Continue support for women’s protection centers and shelters that offer refuge to female victims of violence, especially domestic violence.

To the Afghan Government

- Investigate and prosecute all offenses under the EVAW law, not just those for which there has been an initial complaint by a survivor, and irrespective of whether the survivor withdraws her complaint;

- Strengthen measures to ensure that women and girls are never detained for “running away,” including sanctions and punishments for police, prosecutors, and judges who detain and sentence women and girls who do so;

- Prosecute "virginity tests" as a form of sexual assault, and prohibit the results of such procedures from being used as evidence in legal proceedings; and

- Establish a case management system and uniform criteria for categorizing and collecting detailed data on all reported cases of gender-based violence. While protecting individual privacy, make this data public in an easy to access and use format.

To the Taliban

- Immediately cease all cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishments, including lashings and executions for zina or other crimes.

Methodology

Research for this report took place in Kabul, Mazar-e Sharif, Bamiyan, and Herat, Afghanistan between September 2017 and May 2021. Human Rights Watch interviewed 35 Afghan women and girls who had either registered cases under the Elimination of Violence against Women (EVAW) law or attempted to do so; 9 lawyers representing women in EVAW cases; 8 prosecutors; and 3 judges.

We also interviewed Afghan women rights activists, representatives from the Afghan attorney general’s office, officials from the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA), and international and local nongovernmental organizations providing support for legal aid services and judicial reform in Afghanistan. Most interviews were conducted in person, in Dari and Pashto. Some interviews with officials were conducted by phone.

As the fighting in Afghanistan has intensified in recent years, security outside major urban areas has deteriorated, making it very difficult to interview women in smaller towns or rural areas. Even in urban areas, women are often reluctant to discuss such issues with strangers.

All of the women interviewed were informed of the purpose of the interview, the ways in which the information would be used, and provided anonymity. This report withholds identifying information and uses pseudonyms for most interviewees to protect their privacy and security. None of the interviewees received financial or other incentives.

I. The EVAW Law

In late 2003, delegates from across Afghanistan convened in Kabul to discuss the draft of the new Afghan Constitution, the first since 1964. A fierce debate erupted over article 22, which states that men and women are equal before the law. With pressure from women’s rights advocates and international donors, the article gained enough support to be included in the constitution. However, in the nearly two decades since the 2004 constitution’s adoption, implementation has remained elusive, with some opponents of gender equality arguing that article 22 is limited by article 3, which states, “No law shall contravene the tenets and provisions of the holy religion of Islam in Afghanistan.”

The breakthrough adoption of article 22, and the opening created by the new Afghan government’s ratification of international human rights treaties such as the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) in 2003, represented and gave momentum to efforts to draft a law that would, for the first time, systematically make violence against women a criminal offense.

The Elimination of Violence against Women (EVAW) law came into force by presidential decree in August 2009.

The EVAW law mandates punishments for 22 acts of violence against women, including rape, and obliges the government to take specific actions to prevent violence and assist victims. It also criminalizes violations of women’s civil rights, including depriving a woman of her inheritance or preventing a woman from pursuing work or an education.[1] The Afghan penal code covers other forms of violence against women not covered in the EVAW law, such as murder and kidnapping.[2]

Within the EVAW framework, a survivor of violence may bring a complaint to the Ministry of Women’s Affairs, civil law (huquq) offices, the police, or the EVAW unit in the local prosecutor’s office. Since 2010, the Ministry of Women’s Affairs has registered the majority of cases filed. Once the complaint is registered, it must be referred to the prosecutor’s office for investigation. The Ministry of Women Affairs, which has offices in each provincial center, is meant to maintain contact with the victim and EVAW prosecutors and follow the case through trial.[3]

The provincial-level EVAW units investigate district and provincial-level allegations and the primary and appellate cases. However, in the provinces, outside major urban areas, recognition of the law among officials in the criminal legal system is far more limited. As one lawyer said: “In the provinces, no one recognizes the EVAW law. Even some of the judges who implement the law call it un-Islamic and produced by Westerners.”[4]

Prior to the EVAW law, the 1976 penal code did not define rape as distinct from zina, the crime under Sharia (Islamic law) of unlawful sexual intercourse outside marriage.[5] Through the 1980s, state courts could apply zina to cases of adultery as well as to cases of sexual assault, including rape. However, convictions for adultery under zina by state courts were rare.[6] While the penal code criminalized assault and murder, these were very rarely applied in cases involving relatives due to deeply patriarchal social norms that also make the privacy of the family home paramount. The EVAW law marked an attempt to shift those norms.

Complicating implementation of the EVAW law is that Afghanistan’s legal system is pluralistic, and the applicable—and often contradictory—legal frameworks include the old 1976 and new 2018 penal code, the 2004 constitution, and Sharia law. The constitution explicitly incorporates Islamic Hanafi jurisprudence.[7]

Moreover, at the time the EVAW law was decreed, Afghanistan’s judiciary comprised a diverse group: judges and prosecutors trained in the communist period and accustomed to the old penal code; judges from the post-1992 period when Sharia courts took precedence[8]; and those who had come into office after the defeat of the Taliban government in late 2001. Some judges were educated at secular law faculties, others at Sharia faculties, and others at madrassas, Islamic schools. Their interpretations of the laws varied greatly, and many judges simply ignored written law.[9]

As part of the overhaul of Afghanistan’s legal framework that began with the 2004 constitution, efforts began in 2012 to develop a comprehensive penal code to replace the 1976 code and align it with Afghanistan’s international human rights commitments. Another goal in the penal code drafting process was to consolidate, in one law, penal provisions that were scattered across multiple laws—creating confusion for legal practitioners and cover for those who preferred not to abide by statutory law.

As the revised code neared completion in early 2017, the question of the status of the EVAW law and whether it should be incorporated into the new code sparked controversy. Some Afghan legal scholars and foreign advisors argued that the new penal code contains both a more complete definition of rape and longer punishments for it,[10] and criminalized threats and intimidation to coerce sex.[11] Another article “prohibits the prosecution of rape victims, which potentially signals better protection for women reporting rape.”[12]

However, many Afghan women’s activists argued that keeping the EVAW law as a standalone law was important as a matter of principle, and that maintaining it as “a specific and dedicated law to combat violence against women”[13] would send a stronger message on the need to end impunity for such violence.[14] When the revised penal code was launched in November 2017, the EVAW law remained the only separate law containing penal provisions.[15]

Opponents of the EVAW law have stressed that it was enacted by presidential decree, during a parliamentary recess, and that parliament never reviewed it. Laws passed through such decrees should, by law, be reviewed by parliament within 30 days of the parliamentary session reconvening.[16] At the time the EVAW law was adopted, new legislation was routinely passed by presidential decree during parliamentary recesses; these laws were frequently not presented to the parliament within 30 days.[17]

Parliament has not ratified the EVAW law, and by early 2010, it had been removed from the parliamentary agenda. An attempt to have it reviewed by parliament was swiftly abandoned after vociferous opposition to the law from conservative members who argued that fathers have a right to marry off their underage daughters, and rejected its provisions on polygamy and beating, which some claimed had religious approval.[18]

Despite these political battles, the registration of complaints under the EVAW law and the prosecution of cases has gradually expanded. With the urging and funding of international donors, the Afghan government established specialized police units called “Family Response Units,” prosecution offices, and special courts with female judges to support the law’s implementation.[19]

The prosecution units, piloted in 2010 within the Attorney General’s Office, were present in all 34 provinces as of March 2021.[20] The specialized courts were rolled out beginning in 2018, and are now present, at least in name, in at least 15 provinces.[21] In addition, the government mandated several services for survivors of violence, including free health care, legal aid, and shelters. The shelters, which are not available in every province, face pressure from conservative politicians, including from within the government, as well as insecure and fluctuating funding due to their dependence on foreign aid.[22]

Since the EVAW law was adopted and mechanisms were established to process complaints, the registration of cases of violence has increased.[23] Prosecutors and judges, as well as staff at the institutions mandated to support women, are now better trained.[24] According to one lawyer, appointing legal experts as senior officials, including a deputy attorney general specifically for overseeing implementation of the EVAW law, was particularly important.[25]

In a 2017 report, the UN special rapporteur on violence against women, Rashida Manjoo, noted that while the government had taken steps to implement the law through the establishment of specialized prosecution units and family response units within some police stations, the law was “not implemented to the same degree in the different provinces, with particularly low levels of implementation in rural areas.”[26]

Underreporting remains a serious concern. However, the increase in the number of reported cases may indicate growing awareness and acceptance of the law. Complaints filed by the EVAW unit in the Attorney General’s Office doubled in the first quarter of 2019 (1,106 cases, March-June 2019), compared to the same period in 2018 (545 cases, March-June 2018). Beatings were the most common complaint.[1] In a 2020 report, the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission documented an 8.4 percent increase in reported cases of violence against women from 2018 to 2019.[27]

Despite many hurdles, the gradual implementation of the EVAW law seems to have translated into increased reporting and prosecution of cases. In addition, increased awareness of the need to prevent and punish violence against women lent weight to efforts that achieved some limits on so-called “virginity testing” and made sexual harassment a criminal offense.

II. Obstacles to Justice

Due to social and cultural norms in Afghanistan that regard violence against women as a private family issue or something shameful that should be hidden, women often do not report beatings, sexual assaults, and other forms of violence.

Along with the stigma and social pressure that deter women from filing complaints, the Afghan government’s loss of territorial control has impeded women’s access to justice. By mid-2021, the Taliban either controlled or contested more than half of Afghanistan’s districts.[28] In those areas, government courts do not function. A shortage of trained professionals has also been a factor in slowing implementation of the criminal law elements of the law, and hindering the provision of health care, support, and protection services to survivors.[29]

Police Inaction

Even with the expansion of specialized EVAW institutions, getting police to take violence against women seriously remains an uphill battle, with many police discouraging women from registering their cases at all.[30] EVAW officials have complained that police send them incomplete cases, with critical information missing. [31]

According to one lawyer who has taken on such cases in Herat, “the formal justice system sees the violence cases as a minor issue—they don’t take the EVAW cases very seriously because other types of cases are priorities for the system.”[32] A prosecutor in Mazar-e Sharif pointed out that in many rape cases “the police don’t properly record the case and don’t send it on time. They don’t do a complete investigation.”[33] There is no system in place to prevent police from interfering and even removing files.[34]

Delays in completing case files and obtaining information from police further discourage women from filing complaints. The director of EVAW investigations told Human Rights Watch that women who find the process too difficult and time-consuming often seek a simpler resolution from the local jirga (informal justice councils) because they will provide a remedy through mediation—such as the husband’s promise to refrain from beating—much more quickly.[35]

Corruption is also a factor. Lawyers said that one difficulty they face is that the men implicated in such cases, unlike most Afghan women, have the financial resources to bribe officials not to pursue the case or to rule in their favor.[36]

The influence of powerful politicians, local strongmen, or criminal gangs on behalf of perpetrators is also a factor.[37] A prosecutor in Bamiyan said that, in some cases, local powerbrokers have called her to try to stop a prosecution.[38] In January 2020, for example, local police arrested the father-in-law of Lal Bibi, a 17-year-old girl in Faryab, on charges that he and her husband had beaten her and burned her with boiling water. The husband eluded arrest by going into hiding. Within a month, local strongmen exerted pressure and secured the father-in-law’s release.[39] In other cases, the police may have ties to the accused.

An EVAW official in Mazar-e Sharif said that in many cases the police either do not arrest—or actively cooperate with—the perpetrators.[40] Humaira Rasuli, an attorney and head of the Women for Justice Organization in Kabul, said: “Powerful offenders walk away with impunity, especially in the cases of rape and sexual assault, in Afghanistan because they have the power to conceal or destroy evidence, corrupt officials, and intimidate or pay off witnesses.”[41]

Failure to make an arrest is one of the main reasons cases are not prosecuted. As happened in the case of Lal Bibi, police sometimes say that the perpetrator escaped to an area outside government control. Although this may sometimes happen, lawyers suspect it is also a convenient excuse.[42]

Sitara (pseudonym), a woman who had fled her husband after he injured her with a knife and threw acid on her face, had tried to file a case, and was told her husband could not be found. She said:

It has been two-and-a-half years and they even have not found my husband. They don’t care for my case. I have gone to the police and the [EVAW office] many times—they say that they can’t find my husband. I won’t get peace until he is arrested. If I see him even from a distance, still I will be afraid of him.[43]

Najla (pseudonym), a woman in Herat whose husband frequently beat her, said that when she complained to his parents, they responded that “a husband has such rights.”[44] After she sought help from the Ministry of Women’s Affairs, she escaped to a shelter. Her husband fled and her in-laws have threatened her for shaming the family: “My parent’s family had warned me that when I get out of the shelter, they will kill me. My husband’s family threatened me, and the worse thing is that I don’t have anyone to support me.”[45]

In rape cases, police are often pressured not to make an arrest, while the girl or woman may face charges of zina (sex outside marriage). Sohela (pseudonym), a 17-year-old girl in Bamiyan, was detained in a women’s shelter after reporting that she had been raped. The boy she accused was the son of a prominent family in the district. He was briefly detained and then released. Sohela said:

My friends advised me to go to the Directorate of the Women Affairs. I did and they sent me to this shelter while my case was in process. They registered my case with the police and detained that boy. After a few days, they released him. But the court sentenced me to one year of imprisonment for committing zina. I became pregnant and now have a two-and-a-half-month-old daughter. [46]

The boy’s family tried to pressure the girl to marry him, since she was pregnant, but she refused and remained in the shelter for the rest of her sentence.[47] Human Rights Watch was unable to find out where she went after the sentence was completed.

Lack of Legal Counsel and Problems Proving Abuse

Although an EVAW investigation can commence on the basis of a complaint alone, a conviction often requires the testimony of witnesses or physical evidence, such as documentation from a hospital or clinic. Difficulty acquiring this evidence discourages women from filing complaints. The most likely witnesses would often be family members, who because of social norms may not support the woman’s complaint.

Afghan women are generally less likely than men to seek medical treatment, often because of cost and difficulties in arranging travel to healthcare facilities. Farida (pseudonym), 33, the mother of four children, came to the EVAW unit in Kabul from an outlying rural area in December 2019. Ten days earlier her husband had badly beaten her, but she was unable to travel to a clinic to get treatment or any proof. The investigators told her they could not open a case without witnesses or other evidence. She said: “They told me ‘There are a lot of women like you. We are dealing with this every day.’”[48]

A Kabul-based lawyer said that lack of evidence and witnesses is another reason that women do not register a complaint because if they cannot prove their case, they would have to withdraw it and possibly face charges for filing a false complaint.[49]

Because women often lack knowledge of their rights, they do not know that they are entitled to a lawyer. Even though prosecutors and police are mandated to brief them on their right to counsel, this frequently does not happen.[50] A Kabul-based lawyer said:

Most of these victims do not have access to lawyers. The Ministry of Justice legal aid department only provides lawyers when a victim requests one. But in EVAW cases the victims do not know their rights, they do not know that they can hire a lawyer, or that they should have one—the system does not inform them.[51]

Family Pressure

Women almost inevitably face family and social pressure not to file cases. A lawyer in Kabul said she had “witnessed cases in which the police have allowed a girl to go back home even though they knew that her family would harm her.”[52] Compounding this is the general perception that, as a prosecutor explained with frustration, “A good woman is someone who can tolerate problems and does not ask for her rights.”[53]

An EVAW trial prosecutor told Human Rights Watch that women often say nothing when they are beaten because they are told that to complain is shameful:

They think that they are supposed to tolerate violence [because] in Islam a good woman is someone whose husband is happy with her. There is a belief among many Afghans that when a woman registers a complaint with the authorities then she has dishonored herself.[54]

Financial dependency and the barriers to women living on their own in Afghanistan—which include social stigma and security risks—compound the problem. Women who have experienced spousal abuse face enormous pressures and threats from both families—their own and the husband’s—not to press criminal charges, and to stay silent or accept the decisions of local councils instead.[55] As one EVAW prosecutor said:

Women do not want to break up their families. In Afghanistan, it is not easy to marry again…. People are particularly sensitive [about EVAW]. There have been cases where a husband has told the wife that when you bring your complaint to the police and attorney general’s office, I will not live with you anymore.[56]

Women also must contend with customs and laws that makes it difficult to seek a divorce or to be appointed as the parent with whom children will primarily live, if the parents are not living together.[57] Adiba (pseudonym), 27, filed a complaint with the Kabul EVAW unit after being badly beaten by her husband. The hospital documented her injuries, including a broken arm, and advised her to file a complaint. The case was successfully prosecuted, and her husband was sentenced to six months in prison. However, after he was released, he forced Adiba to leave the house and cut her off from contact with their child. At the time of the interview, she was living in a women’s shelter in Kabul.

“My husband refuses to live with me,” said Adiba. “He will not let me return and he will not divorce me. He says I have caused shame to the family. My parents also say what I did was wrong. I do not know what to do.”[58]

Shelters remain a lifeline and a last resort for women and girls who need to escape abuse at home. In a case Human Rights Watch investigated in Herat, Fereshta (pseudonym), 15, who was repeatedly beaten by her parents and illegally married off when she was 6, obtained a divorce when she was 13 after her brother brought her to the office of the Ministry of Women’s Affairs.[59] Because she could neither return to her parents’ home or her former husband’s, she was sent to live in a shelter. She had been there for two years when Human Rights Watch spoke to her. She said: “I don’t want to live with my brothers. I don’t want to return home. Nobody comes to visit me here, but I have safe housing and attend school.”[60] No case was filed against her parents or her ex-husband.

Parveen (pseudonym), a woman in Balkh province, had been forced to marry at 12. After many years of enduring abuse, she finally filed a case against her husband after he beat her and shackled her feet so she could not leave her room. Her nephew helped her escape and go to the police station. The case went to trial and her husband was convicted, but he was sentenced to only four months in prison. When Human Rights Watch spoke with her, Parveen had been living in the shelter for six months and had not seen her children in that time. “I want a divorce,” she said. “I want to stand on my own feet, and I want my children.”[61]

Mediation

One of the factors weakening implementation of the EVAW law is overreliance on mediation to resolve cases, including in cases involving extreme physical violence. Although the EVAW law does not mandate family mediation or alternative dispute resolution in cases of physical violence, it is almost invariably part of the process once a complaint is filed. One lawyer said mediation happens at every stage. “They even threaten the victim that if you go through with your case, you will be divorced.”[62] In its 2018 report, UNAMA found that 61 percent of the cases it followed were resolved through mediation.[63]

Article 39 of the EVAW law allows the complainant to withdraw her case for most of the 22 criminalized acts of EVAW except for the five of the most serious crimes: sexual assault, forced sale of sex, publicizing the identity of the victim, burning or using chemical substances to cause harm, and forced self-immolation or suicide.[64] The investigation and prosecution of murder—which comes under the penal code—does not depend on a complaint being filed.

All other acts, including beating, child and forced marriage, and buying and selling women or girls, can be resolved through mediation. This provision in the law has allowed family members, police, and prosecutors to encourage or coerce women to withdraw their complaints and seek mediation rather than pursue their cases in court.

In many mediation cases, after a woman registers a complaint and has been assigned a lawyer, the EVAW office assembles a committee comprising representatives from the police, Ministry of Women’s Affairs, Justice Ministry, family court, prosecutor’s office, and the local office of the human rights commission. This committee meets separately with both parties. After the committee obtains the consent of the woman—without guarantees that this consent is voluntary, informed, and freely given—the committee members mediate the case in her presence.[65]

UNAMA has noted that while survivors are generally present during mediation proceedings, “mediation is unregulated … and consequently EVAW Law institutions do not apply uniform standards and procedures, resulting in varying levels of duty of care.”[66]

The procedures for mediation can be one more factor creating pressure for the woman to withdraw her complaint. If the husband does not attend, mediation cannot move forward. Mariam (pseudonym), who had been married when she was 6 and whose husband frequently beat her, said that she tried mediation, but her husband did not attend, so it could not go forward.

She said that she did not initially go to the police because “I thought our situation may improve, I thought our life might get better over time, but it didn’t get better.” When she finally sought to file a criminal case against her husband, police said they were unable to apprehend him. When Human Rights Watch spoke with her, she was living in a shelter.[67]

Hamida (pseudonym), a resident of Balkh province, was beaten by both her husband and father, who threatened to provide her husband with a weapon to kill her if she continued to complain. After a severe beating that left her with head injuries and a broken arm, her sister-in-law took Hamida to a shelter. Hamida said:

The prosecutor and my attorney told me to return home and sacrifice myself for my children. They say that now your head and arm have healed, go back to your home. But I told them I have not come to a hospital only to go back home. My life won’t get better there.[68]

Because remedies reached through mediation are not binding, they may fail to provide women with any relief. Aziza (pseudonym), who was about 21, said that after her husband beat her, they went through several mediation processes:

In the past three years, 10 mediation sessions were held. On the last one, they decided that my husband should compensate by giving me 50,000 AFS [US$670] as a fine and should not beat me anymore. But the decisions were not implemented, because they were not binding to him. [69]

When he began beating her again, she filed a complaint. He was sentenced to one year and two months in prison, and she went to live in a shelter.[70]

Zakia (pseudonym), 22, married for four years, said that her husband frequently beat her and eventually threw her out, saying he wanted to marry someone else. She said she and her husband had attended many mediation sessions but although he promised to stop beating her, he resumed again immediately after, and often more severely. Despite this, she said received no support for pursuing a criminal case:

The police advised me not to officially register a case and told me to return home. The appellate court judge told me to withdraw my complaint and return home. My brother told me not to ask for a divorce and compromise with my husband even if he marries a second woman, and to stay and take care of my children.[71]

The financial dependence of Afghan women on male breadwinners is also a factor in their withdrawing complaints. The EVAW law relies on imprisonment as a deterrent, but the lack of alternatives to prison can also discourage women from filing complaints.[72] With the perpetrators being in many cases the family’s sole breadwinner, women may not be willing to risk losing that support for the duration of a prison term, leaving some survivors to “withdraw their cases and seek mediation because they lacked other alternatives, given their dependent financial and family situation.”[73]

UNAMA has noted that EVAW institutions sometimes fail to prosecute cases that fall under the category of serious crimes for which withdrawing the complaint is not allowed, including “33.3 percent of cases of forcing into prostitution, 4.2 percent of rape cases, and 12.5 percent of cases of forcing into self-immolation or suicide,” because the woman or her lawyer withdrew the complaint.[74]

In its 2018 report, UNAMA noted that in a large number of mediated cases women agreed to the final decision, even when it was not to their benefit, due to no other viable options and no independent means of sustaining themselves and their families.[75] UNAMA has recommended that the Afghan government “develop robust mechanisms for alternatives to imprisonment that would apply to the less serious criminal offences of violence against women—the vast majority of which are currently mediated.”[76] According to one lawyer involved in drafting proposed amendments to the EVAW law, as of June 2021, discussions were underway about possible alternatives, including cash fines, for some crimes.[77]

Other factors contributing to widespread mediation of criminal offenses of violence against women and underreporting of complaints to authorities include real and perceived corruption among police, prosecutors and judges, and fear of long adjudication processes.[78]

“Honor Killings”

The 2018 penal code removed “honor” as a mitigating factor for murder cases; the previous penal code, in force since 1976, had allowed for greatly reduced sentences in cases where “honor” was cited as a defense.[79] Yet during the decade the EVAW law has been in force, there has been very little progress in ending impunity for “honor killings.”

Family members—most often brothers or fathers—often commit such murders to punish a girl or woman who has run away from home. The women and girls killed in this manner were often fleeing to escape violence or a forced marriage. Only about one-third of such cases are ever prosecuted, and less than 25 percent of the perpetrators are convicted.[80] The vast majority of such cases are never investigated or prosecuted, as police fail to arrest the perpetrators or forward cases to prosecutors.[81]

“Virginity Testing”

So-called virginity examinations have been a routine part of criminal proceedings in Afghanistan even though they have no scientific validity.[82] When women or girls are accused of “moral crimes,” such as sex outside of marriage, police, prosecutors, and judges regularly send them to government doctors to perform these examinations to determine whether they are “virgins.” The conclusions they draw about the women’s sexual histories are used in court as evidence and have led to long prison terms for many women.

Advocacy by Afghan women’s rights organizations and forensic science professionals have succeeded in bringing about some changes in the law. In July 2017, the Afghan Ministry of Public Health issued a new policy instructing government health workers not to perform these examinations.[83] In September 2020, human rights organizations called for a total ban on so-called virginity tests.[84]

The 2018 Afghan penal code requires a court order and the consent of the woman for the test. However, such changes in policy are often ignored and have little impact when not coupled with effective monitoring of compliance by justice sector officials and the doctors who perform the examinations.[85]

In 2020, the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission (AIHRC) found that the practice continued despite the reforms.[86] The AIHRC surveyed 129 women who had so-called “virginity examinations” after the penal code change went into effect. It found that in 92 percent of cases there was neither consent nor a court order. Four respondents said a man conducted the examination, which violates Afghanistan’s Criminal Procedure Code.[87]

Over a two-month period in 2017, during the investigation and trial of a case of alleged sexual assault of two girls, ages 6 and 7, the prosecutor and judge sent the victims for “virginity” examinations three times—long after there would have been any forensic value to the tests. Because the “virginity test” could not prove that penetration had occurred, the judge threatened the midwife who had first examined the children and reported suspected sexual assault, saying, “I could sentence you to imprisonment for false reporting [of rape].”[88] The midwife told Human Rights Watch she would never report such a case again.[89]

III. Taliban Courts on Violence against Women

As Taliban forces have increased their control over Afghan districts formerly administered by the government, residents have been subjected to Taliban-imposed regulations governing schools, health care, government services, and public life, including their movements outside the home. Taliban leaders have assumed oversight of government services and have issued regulations concerning their operations. This divided state, and the prospect of a peace agreement or coalition government, have raised a number of critical questions about the protection of women’s and girls’ rights in the future.

Taliban courts offer very limited options for women seeking justice in cases of family violence. While women in Taliban-controlled areas have access to Taliban courts, they may not always represent themselves. In Helmand, for example, while some women have appeared in Taliban courts, others do not do so because of family opposition to appearing in public and rely on male relatives to represent them.[90]

Taliban courts hear a small number of domestic violence cases, and generally pressure the parties to resolve such disputes at home. This approach mirrors the deficiencies of government courts that press women to pursue mediation within the family, but with no option for criminal prosecution, it is an approach that leaves women and girls with no recourse but to “forgive” their abusers and continue to live in the same household and, often, continue suffering violence.[91]

A woman in Helmand observed that it was highly unlikely that “the Taliban would arrest someone who had beaten his wife or any other female member of the house.”[92] In such cases, Taliban officials would normally press the relatives to resolve the problem in the home, and for the woman to drop any complaint.[93]

Taliban courts have also imposed harsh punishments for “moral crimes,” including zina. In such cases, the Taliban have sentenced the accused to cruel punishments that include lashing and, in some cases, execution. In an interview with The Guardian, a Taliban judge in Obe district, Herat, spoke of an adultery case over which he had presided in April 2021: “I recently ordered the flogging of a woman inside her home. Relatives and neighbors came to us and said there were witnesses to this man and woman being together. We lashed her 20 times.”[94]

The United Nations has also documented cases in which Taliban courts sentenced women to lashing for committing adultery or having “immoral relationships” with men. In a November 2019 case in Kohistan, Faryab, Taliban officials charged a man and woman with “elopement” after the woman fled from an abusive situation in her home, a “crime” for which the Taliban usually impose a death sentence. Her father and brother, who were Taliban members, carried out the sentence, fatally shooting her.[95]

The Taliban oppose shelters for women fleeing abuse at home, and none exist in areas under their control. Taliban officials have told Human Rights Watch that in a case where a woman could not return home, local Taliban authorities would arrange accommodation for her in the community by rehousing her with another family—not necessarily with her consent.[96]

Recommendations

This report is being published as the United States completes its troop withdrawal from Afghanistan and the Taliban is increasing its hold on the country, leaving uncertain the survival of the post-2001 Afghan state. It is vital that Afghanistan’s international partners continue supporting efforts to protect women and girls from violence and to hold perpetrators to account.

To Donors

- Advocate forcefully that all parties preserve rights protections as provided for in the 2004 constitution and the laws of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, including the Elimination of Violence against Women (EVAW) law;

- Continue support to initiatives aimed at enforcement of the EVAW law, including training for professional staff and technical assistance and support for provincial prosecution offices and courts; and

- Continue support for women’s protection centers and shelters that offer refuge to female victims of violence, especially domestic violence.

To the Afghan Government

Services

- Provide support for survivors of gender-based violence, including:

- A new government-supported national crisis hotline for women and girls experiencing gender-based violence, and ongoing national outreach so that it becomes widely known;

- Free health care and psychological support for survivors;

- Free legal assistance for all survivors, including in seeking: orders of protection, prosecution, divorce, child custody, child support, alimony and marital property; and

- Expanded support and coverage of Women Protection Centers, with a minimum of one in every province, to ensure that all survivors of violence are able to access shelter and safety after experiencing violence.

- Expand services within healthcare facilities specifically targeted at assisting survivors of gender-based violence; and

- Expand support to legal counsel, paralegals, and legal aid networks to ensure survivors of violence—particularly in remote and rural areas—can access free information about their rights and assistance in accessing justice for crimes of violence, including representation.

Justice

- Investigate and prosecute all offenses under the EVAW law, not just those for which there has been an initial complaint by a survivor, and irrespective of whether the survivor withdraws her complaint;

- Strengthen measures to ensure that women and girls are never detained for “running away,” including sanctions and punishments for police, prosecutors, and judges who detain and sentence women and girls who do so;

- Issue instructions to police and prosecutors that they may not bring “attempted zina” charges;

- Establish a system to receive complaints regarding the administration of “virginity tests” and appropriately discipline, including through dismissal, government employees involved in conducting such procedures;

- Prosecute “virginity tests” as a form of sexual assault, and prohibit the results of such procedures from being used as evidence in legal proceedings;

- Establish a case management system and uniform criteria for categorizing and collecting detailed data on all reported cases of gender-based violence. While protecting individual privacy, make this data public in an easy to access and use format;

- Expand efforts to provide safe and confidential spaces to ensure survivors of violence report crimes in safety and dignity; ensure Family Response Units have separate workspaces and office equipment;

- Train all police officers and EVAW prosecutors on Afghanistan’s Gender-Based Violence Treatment Protocol; and

- Expand support to defense counsel, paralegals, and legal aid networks to ensure survivors of violence can access free information about their rights and assistance, including representation, in obtaining justice for violent crimes.

To the Taliban

- Immediately cease all cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishments, including lashings and executions for zina or other crimes;

- Ensure that women and girls are never punished for “running away;”

- Permit nongovernmental organizations to continue to provide support for survivors of gender-based violence, including:

- Women’s protection centers and shelters that offer refuge to female victims of violence;

- Free health care and psychological support for survivors; and

- Free legal assistance for all survivors, including in seeking: orders of protection, prosecution, divorce, child custody, child support, alimony, and marital property.

- End all summary punishments of residents, including women and girls, who have violated local regulations regarding dress and appearance, playing of music, and other behavior that is protected by international human rights standards; and

- Respect the rights of different ethnic and religious communities to observe diverse practices with respect to attire, music, and other social activities.

Acknowledgments

This report was written by Fereshta Abbasi, a consultant with Human Rights Watch, and Patricia Gossman, associate Asia director at Human Rights Watch. Heather Barr, acting co-director of the Women’s Rights Division, provided additional input and specialist review. Brad Adams, executive director for the Asia Division, edited and provided divisional review. James Ross, legal and policy director, provided legal review, and Danielle Haas, senior editor, provided program review. Editorial and production assistance was provided by Racqueal Legerwood, Asia senior coordinator; Travis Carr, digital publication coordinator; and Grace Choi, digital publication director. The report was prepared for publication by Jose Martinez, senior coordinator, and Fitzroy Hepkins, administrative manager.

Human Rights Watch wishes to thank all those in Afghanistan who agreed to be interviewed. In deference to their concerns, we have honored their requests for anonymity.