In the Ancient Roman Circus, when a gladiator fell, his fate was decided not by a judge and jury, but by the will of the emperor and the crowd. Now President Andrés Manuel López Obrador is doing something similar with Mexico’s justice system.

This Sunday, August 1, Mexicans will be asked to vote in a referendum on the following question: “Do you agree that pertinent actions should be taken, in adherence with the laws and constitution, to begin a process to clarify political decisions taken in previous years by political actors, with the aim of guaranteeing justice and the rights of possible victims?”

Pundits have debated the meaning of this vaguely worded question, written by the Supreme Court after it rejected the original version drafted by lawmakers from Lopez Obrador’s Morena party. But López Obrador, who first proposed this referendum before taking office in 2018, and who has relentlessly pushed for it since then, has made crystal clear what the question means and how he intends to proceed if the outcome is positive.

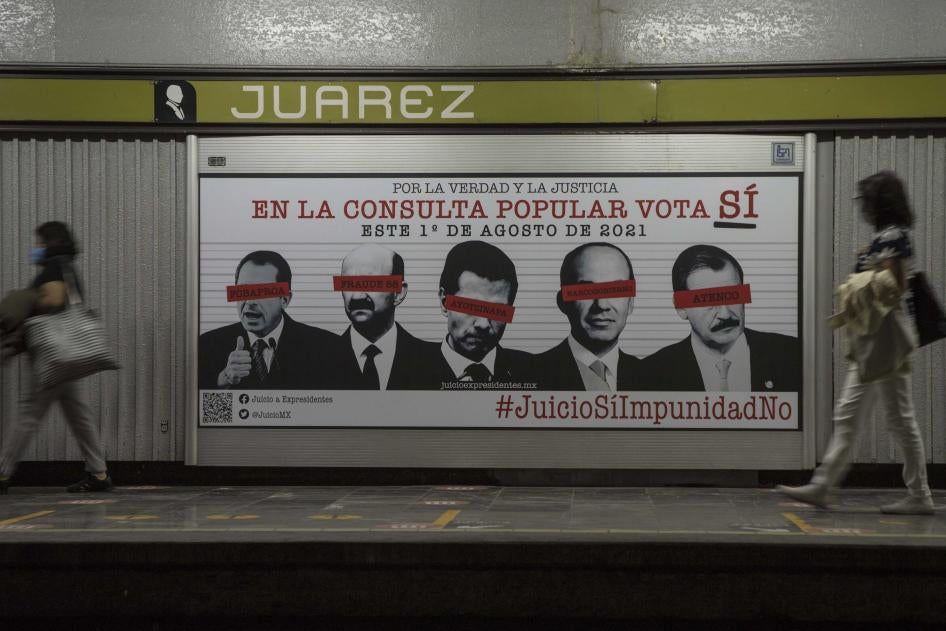

“It is a question that can be translated simply,” he explained at a news conference last month. “Do you want former presidents Carlos Salinas, Ernesto Zedillo, Vicente Fox, Felipe Calderón, and Enrique Peña Nieto to be investigated and put on trial, in accordance with the law? Yes or no. The text is different, but in essence, that’s it.” He even outlined the specific offenses for which he believes each past president should be put on trial. Campaigners for the referendum have been more direct. “Do you want Salinas, Peña, and Calderón to go to jail?” read their signs.

The president and his supporters have framed this referendum as an exercise in the rule of law and a way to end the impunity that plagues Mexico. In truth, it is the opposite. This Sunday’s referendum makes a mockery of the most basic tenets of the rule of law and threatens to further entrench the deplorable culture of impunity that stands in the way of justice for countless victims of crimes, including serious human rights violations committed by government agents.

There is no legal impediment to investigating possible crimes committed by former presidents since the constitution does not grant immunity to public servants after their terms expire. Attorney General Alejandro Gertz Manero can open such an investigation at any time. He can do so right now. In fact, if he has credible evidence that a crime has been committed, it is his duty to investigate to ensure justice for the victims. No referendum is required for the country’s top justice official to do his job.

By the same token, no referendum can annul the right of victims. Even if Mexicans overwhelmingly vote ‘no’ on Sunday, victims still have the right to justice, and the attorney general still has the duty to investigate any possible crimes and do everything in his power to ensure that justice is served.

On the other hand, if the attorney general does not have credible evidence that former presidents have committed crimes, then no referendum can create that evidence or force him to discover it. And no referendum can compel a judge to indict or convict a suspect without evidence. Even a former president.

The referendum is only binding if 40 percent of eligible voters participate. However, even if that happens, it is hard to understand how the outcome of the referendum would be anything but a complete perversion of the rule of law.

The concept of the rule of law is simple. A country has laws. They should be applied equally and fairly to everyone, even the rich and powerful. They should not be applied arbitrarily, based on political decisions or popular referendums. Ensuring that everyone is equal before the law is fundamental to protecting and defending human rights – and only a criminal investigation and conviction that is based on due process guarantees will ensure people’s trust in the outcome of judicial decisions.

Mexicans know what it is to live with weak rule of law. Mexican police and prosecutors frequently fail to take basic steps to solve crimes and have too often relied on information obtained through torture, instead of proper investigations. The law is often applied selectively, or not at all. Those who commit serious human rights violations regularly escape justice. Just under two percent of crimes in Mexico are resolved. Unsurprisingly, many Mexicans are frustrated.

Their frustration will not be addressed by a referendum that will inevitably further jeopardize Mexico’s judiciary by making it López Obrador’s political tool and setting a dangerous precedent that laws can be applied or waived depending on what is politically expedient. If the Mexican people want a justice system that investigates crimes and protects their rights, they should press López Obrador to respect the autonomy of the justice system and press state and federal attorneys general to comply with their responsibilities to be transparent and respect the rights of victims.

Mexicans deserve a justice system that they can count on. This referendum is not only a travesty for the rule of law; it’s simply a political circus.