- What are the risks of lead poisoning? Who is most at risk?

- Why is Human Rights Watch concerned about lead contamination at the Mavrovouni migrant camp, on Lesbos?

- What were the results of the testing?

- Is the testing that the government commissioned sufficient?

- Does the EAGME report accurately reflect the risk of lead exposure at the camp?

- What expertise does Human Rights Watch have to comment on this issue?

- So, is the camp safe for people living and working there?

- Is contaminated soil really a problem, since people are exposed to lead all the time?

- The Greek government has dismissed the relevance of scientific studies on lead contamination at firing ranges, saying this research only found that shooters inhale lead while shooting but did not examine soil contamination. Is this true?

- The Greek government has also said that comparisons to the situation at a contaminated displaced persons’ camp in Kosovo are not relevant. Is this true?

- What should the Greek government do now?

Lead is a heavy metal that is highly toxic for humans when ingested or inhaled, particularly for young children and during pregnancy and lactation. Elevated levels can impair the body's neurological, biological, and cognitive functions, leading to learning barriers or disabilities; behavioral problems; impaired growth; anemia; brain, liver, kidney, nerve, and stomach damage; coma and convulsions; and even death. Lead also increases the risk of miscarriage and can be transmitted through both the placenta and breast milk.

Children are especially at risk because when exposed to the same levels they absorb four to five times as much lead as adults, and their brains and bodies are still developing. In addition, small children often put their hands in their mouths or play on the ground, which increases their likelihood of ingesting or inhaling lead in dust and dirt. Exposure during pregnancy can result in stillbirth, miscarriage, and low birth weight, and can negatively affect fetal brain development.

- Why is Human Rights Watch concerned about lead contamination at the Mavrovouni migrant camp, on Lesbos?

In September 2020 Greek authorities built the Mavrovouni migrant camp, currently housing 6,900 women, men, and children, on a repurposed military firing range that was in use from 1926 to September 2020, just before the camp was established. After media reports in October publicized that the camp was built on a military site, Human Rights Watch urged the Greek government in early November to test the site for lead. According to the government, 21,000 square meters of the camp were within the area of the former firing range. Firing ranges are well recognized as sites contaminated by lead.

At least 118 pregnant women and 2,552 children live in the camp, according to government data provided to Human Rights Watch in November, and at least one pregnant aid worker is regularly inside the camp. Given the risks from lead exposure for small children and during pregnancy, Human Rights Watch has been concerned about acute risks from potential soil contamination.

After testing soil from the Mavrovouni camp in November 2020, the Greek government made public on January 27, a report by the Greek Institute of Geology and Mineral Exploration (EAGME) confirming the presence of elevated lead levels in some areas of the temporary migrant camp.

Researchers took a total of 12 soil samples from the camp, three of them in the area of the former firing range. Test results from soil next to an administrative area inside the camp and within a residential area of the camp at the former firing range, showed elevated levels of lead. Soil from the administrative area was found to have 2,233 mg lead/kg soil (sample “MAV-1”) and soil from the residential area was found to have 330 mg/kg (sample “MAV-12). According to Greek authorities, the maximum acceptable levels of lead in soil for playgrounds is 100 mg/kg. The ‘playground’ standard is the appropriate measure to apply to the camps as children are found throughout the camp.

No. The Human Rights Watch analysis and an analysis by experts of the EAGME report shows that the testing regime was insufficient to assess the extent and severity of lead contamination at the camp and risks to people’s health, and that there is an urgent need for further testing.

Out of the 12 samples taken from the entire camp, EAGME only took three samples from the firing range, an area of 21,000 square meters that is the most at risk of contamination, and one from the hill behind the range, where some munitions may have landed. The sample taken from the foot of the hill, however, was not taken from the area on the hill that Human Rights Watch and experts are most concerned would have elevated lead levels. It was taken from further north than the expected line of fire from the range, and not downslope from where one would expect projectiles fired from the range to be landing on the hill.

During a February 1 meeting between the Migration Ministry and nongovernmental organizations attended by Human Rights Watch, an EAGME researcher said that the aim of the testing was a “preliminary mapping” of the entire camp rather than a thorough analysis of the areas most at risk of contamination. Despite this, a government representative at the meeting said that there are no plans for comprehensive testing until after ongoing construction, including soil remediation efforts, are completed at the camp. There is an urgent need for further testing, particularly near the areas where elevated lead levels, 2,233 mg/kg (sample “MAV-1”) and 330 mg/kg (sample “MAV-12”), respectively, were found. The EAGME report also fails to address questions about the sampling methodology used including the rationale for the depth of samples, and whether sample locations were from areas of new or old soil; or where the new soil came from, where exactly it was placed in the camp, and where the old soil was taken if any was removed.

No. The scope of testing was insufficient, information regarding whether soil samples were from new or old soil was excluded, and the EAGME report and government downplay the risk of elevated lead levels found in two of the samples by incorrectly referencing less stringent standards than should be used.

The government stated that the results of lead levels taken from soil samples at one site in the administrative area, “MAV-1,” were within the acceptable range by referencing lead level soil standards for industrial areas. Those standards are designed for industrial areas where workers wear protective equipment and children are typically not present. However, the sample was taken next to an administrative area inside the camp on the Mavrovouni hill where at least four aid organizations have their offices, with many employees working there without protective equipment.

Residents, sometimes as many as 200, including children and residents who are pregnant or lactating, line up for support and information there for hours. Given this reality, the government should at least have applied the standards it references for residential areas, which the “MAV 1” sample exceeds by more than four times.

The report also references the national lead limit for residential areas, 500mg/kg, to assert that none of the other 11 samples taken in residential areas of the camp are above safe levels. However, due to the way the camp is used by residents, including children playing in the dust, the comparison of test results for a playground (100 mg/kg) and not residential (500 mg/kg) are more appropriate to assess the potential risk to children’s health in this setting. Two of the 11 samples taken from residential areas of the camp exceeded this standard of 100 mg/kg, as referenced in the report, including in particular “MAV-12.”

The lead levels found in the “MAV-12” sample are taken from an area where the former small arms firing range was and is now within the residential area of the camp, where about 50 tents housing migrants were present at least up until February 5. While the levels were technically within the Greek limits of lead levels in residential areas, they were three times above the playground limits and significantly higher than the other samples taken in residential areas. This suggests that the firing range soil is contaminated, or that contaminated soil from the hill may have moved or been brought down to areas at the foot of the hill. Further testing is required to better understand the origin and extent of contamination.

Further, the report does not make clear whether the samples taken came from areas where new soil was added during construction and anti-flooding works. If that is what happened, there is a risk that there are still areas of the firing range with pockets of old soil, which will have higher levels of lead. Only comprehensive and targeted testing will be able to assess and mitigate that risk.

Human Rights Watch has investigated lead impacts on the health of marginalized and at-risk populations for more than 12 years, and advocated for the rights to health and a healthy environment in relation to lead poisoning in Kosovo (2009), China (2011), Nigeria (2012), Kenya (2014), Thailand (2014), Kosovo (2017), USA (2018), and Zambia (2019). This is a human rights issue because governments have a duty under human rights laws to protect people’s health and inform them about the risks of lead poisoning.

Experts from the Human Rights Watch environment, health, crisis, and European divisional teams analyzed the results and scope of the soil testing commissioned by the Greek government. The conclusions incorporate the expert analysis and advice of Dr. Jack Caravanos, professor of global environmental health at New York University; Dr. Gordon Binkhorst, vice president of global programs at Pure Earth, and Dr. Mary Jean Brown, former chief of the Lead Poisoning Prevention Branch at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Each independently reviewed the testing results.

Lead levels found by the administrative tents (“MAV-1”), and in the nearby residential area (“MAV-12”), are not safe for young children or people who are pregnant, and both areas should be immediately fenced off and not used until they have been successfully remediated. There is also a significant risk that other areas of the hill and firing range that were not tested may have elevated lead levels that make it unsafe for people living there.

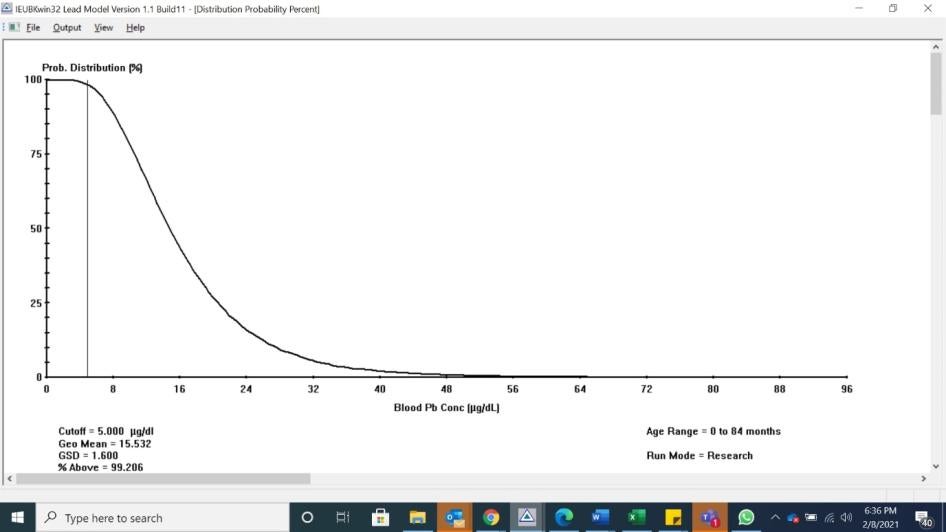

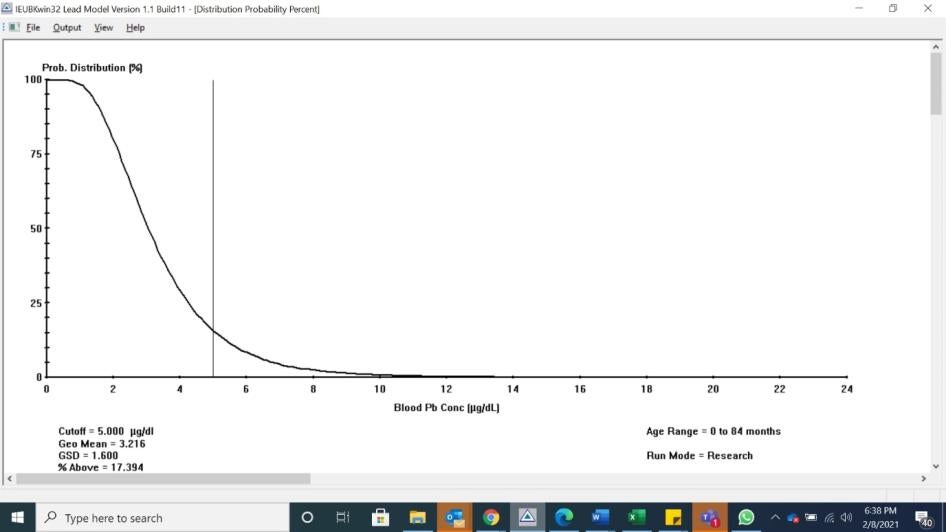

Human Rights Watch, under the guidance of an environmental health expert, ran a simulation using a well-established scientific model to estimate the blood lead levels of children ages 7 and younger living in Mavrovouni using the limited results from the EAGME report. The model used conservative inputs that assume children are only exposed to lead through soil, and not through air, water, or food, and that they do not have existing lead concentrations in their blood. The model found that children ages 7 and under being exposed for even a short time to the elevated levels measured by the government have a significant risk of having a blood lead level above 5μg/dL. This level is identified by the United States’ Center for Disease Control as a level that requires further public health action.

However, it is unclear whether people in other parts of the camp are at risk of exposure to unsafe levels of lead because the scope of the government testing was too limited in terms of the number of soil samples taken and their location.

Lead is found at low levels in the natural environment. However, the widespread occurrence of lead in the environment is largely the result of human activity, such as mining, smelting, refining, and recycling of lead; use of leaded petrol and aviation fuel; use of lead in manufacturing, such as for lead-acid batteries, paints, glazes, and leaded glass; in jewelry making, soldering and ceramics; as part of electronic waste; and use in water pipes and solder.

Lead exposure is estimated to account for more than 1 million premature deaths and 24 million years of healthy life lost worldwide each year. The World Health Organization maintains that there is no level of exposure to lead that is known to be without harmful effects and health authorities around the world have increasingly lowered the admissible thresholds for lead in soil, water, dust etc. Even low blood lead levels in children have been linked to low IQ, increased emotional and behavioral problems, and delayed physical development.

The dusty conditions in Mavrovouni camp mean that residents and staff are much more likely to be exposed to contaminated soil. The presence of dust, particularly in areas found to be contaminated, is a real cause for concern because lead is commonly inhaled or ingested via contaminated soil or dust. Camp residents also have limited access to water to wash off contaminated soil.

Residents interviewed by Human Rights Watch have said that in dry weather, cars driving on the gravel roads inside the camp and other activity stirs up dust and they have to clean it from their tents multiple times a day. Human Rights Watch researchers have seen photos of children playing in dusty areas and digging holes in the ground where the former firing range was, and on the hill behind the firing range.

The government is also moving soil in the process of doing considerable construction at the camp, as part of anti-flooding and other works, creating more dust and potentially leading to contaminated soil being moved around in the camp, spreading the risk of exposure.

According to aid workers, the government is moving soil from one area of the hill to other parts of the camp including the firing range and the area at the foot of the hill where sample “MAV-1” was taken. Because there was no testing done of soil from that part of the hill, there is a risk that the soil being moved around is contaminated.

- The Greek government has dismissed the relevance of scientific studies on lead contamination at firing ranges, saying this research only found that shooters inhale lead while shooting but did not examine soil contamination. Is this true?

No. Research on lead contamination at firing ranges investigates both the impacts during shooting and the impacts on soil. Research at firing ranges has found that the discharge of lead dust from shooting results in long-term soil contamination, which can expose people to lead when the area is not remediated.

- The Greek government has also said that comparisons to the situation at a contaminated displaced persons’ camp in Kosovo are not relevant. Is this true?

Regarding Kosovo, while the source and extent of lead exposure at the Kosovo camps was different (a large smelter) from Lesbos (a firing range), the exposure routes and vulnerabilities of people living in the camp are similar. As a result of people living in tents and children playing in the dust, it is expected that they will be exposed very acutely to contaminated soil. However, it is not possible to compare the extent of contamination and specific health impacts without comprehensive testing.

While the length of exposure does increase risks associated with lead exposure, people exposed to elevated levels can suffer health consequences within short periods. In Kosovo, high levels of lead were found in blood samples within a year of people moving to the camp, a similar amount of time that residents in Mavrovouni could be exposed to lead if they move to a new camp in autumn 2021, as the government has promised.

The Kosovo camps were established between September 1999 and January 2000. In August 2000, testing of French KFOR soldiers serving near its facilities revealed that their blood lead levels had increased dramatically. KFOR contingents took measures to protect their personnel, including removing personnel with high blood lead levels from the area. In November 2000 UNMIK commissioned an internal report, with researchers finding extremely high concentrations of lead in vegetation, soil, and dust. They also stated that particularly high blood lead levels had been recorded in the Roma living in the camps.

Following the release of the EAGME report, the Greek government committed to taking some mitigation measures, including adding new soil and gravel on top of contaminated soil; limiting access to the area where elevated levels of lead were found at the foot of the hill; undertaking further testing once sewage and other construction works have been completed to confirm absence of elevated lead levels; and sharing information with civil society organizations, employees, and other actors involved. These are positive steps and should be pursued expeditiously.

The Greek government should also immediately carry out additional comprehensive testing in the areas at highest risk of contamination to help develop its remediation measures. Unless it does this, it will not know which soil is safe and which is contaminated, and consequently what the health risks are and how to mitigate them. When conducting further tests, the government should ensure that all relevant information about the soil history is shared with researchers and that the full methodology is made public along with results.

It is vital for EAGME to share the scope of planned work (i.e., the testing plan) with international experts for review and seek input on testing and remediation measures before doing more testing.

Until further testing is conducted camp authorities should fence off the areas near “MAV-12” and “MAV-1” where contaminated soil was found and inform residents and staff, especially people who have small children, are pregnant or lactating, about the measures taken and the risks of lead exposure, which the authorities have failed to do so far.

Given the elevated levels of lead in at least two areas, small children between 9 months and 2 years spending time in these areas should be offered free blood testing because they are most at risk of severe lead poisoning. In early February, the government told aid workers that if some camp residents have lead poisoning, it might be a result of prior exposure to lead. It is indeed possible that people have been exposed to lead prior to arriving in the camp and this makes it all the more important to ensure that no additional exposure happens in the camp. If elevated blood lead levels are found in residents or staff they should be urgently treated, irrespective of their origin.