(New York, September 7, 2017) – The United Nations’ failure to compensate victims of widespread lead poisoning at UN-run camps in Kosovo has left affected families struggling to care for sick relatives who were exposed to the contamination, Human Rights Watch said today.

About 8,000 people from the Roma, Ashkali, and Egyptian minorities were forced from their homes in Mitrovica town after the 1998-1999 Kosovo war. For more than a decade, the UN – Kosovo’s then-de facto government – resettled about 600 of them in camps contaminated by lead from a nearby industrial mine. In 2016, a UN human rights advisory panel found that the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK) had violated the affected people’s rights to life and health. It said that UNMIK “was made aware of the health risks [camp residents] had been exposed to since November 2000,” yet failed to relocate them to a safe environment until more than 10 years later and recommended it apologize and pay individual compensation.

Despite the human rights panel’s recommendations, the UN announced in May 2017 that it would create only a voluntary trust fund for community assistance projects to help “more broadly the Roma, Ashkali and Egyptian communities” – staying short of a public apology or acceptance of responsibility.

“The UN should stop ignoring its own experts’ sound advice and compensate the people who are experiencing lifelong damage and hardship due to the UN’s shortcomings,” said Katharina Rall, environment researcher at Human Rights Watch. “How can the UN expect to effectively press governments to take responsibility for their abuses if it won’t do the right thing for the harm it caused?”

In June, Human Rights Watch interviewed 19 victims of lead poisoning and family members who had lived in UN-run camps, as well as medical practitioners, lawyers, and organizations supporting the affected communities.

Human Rights Watch found that many of those affected, including children, are experiencing myriad health problems, including seizures, kidney disease, and memory loss – all common long-term effects of lead poisoning. Lead is highly toxic and can impair the body’s neurological, biological, and cognitive functions. Children and pregnant women are particularly at risk. A 33-year-old woman who lived in a contaminated camp and then relocated to the Roma district of Mitrovica town said she worries about her 16-year-old son, who was 9 months old when he tested positive for lead poisoning: “Until he was 7 he experienced regular seizures. Today he … is struggling at school. He is often nervous and has a hard time remembering things. As a mother, it is very difficult for me to see my children in this condition and not be able to help.”

The UN’s Human Rights Advisory Panel investigated complaints of human rights violations by UNMIK, which governed Kosovo after 1999. The panel found violations of several human rights, including the rights to life, health, and nondiscrimination. The announcement by the press office of UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres in May that the UN would create a voluntary trust fund rather than compensate individual victims means that no action will be taken unless UN member states choose to donate to the fund, making any timely redress for victims highly uncertain.

In July 2017, Guterres called upon the member states to support the trust fund in order to address “the most pressing needs of the affected communities.” While the UN said it “is making every effort to mobilize resources,” it offered no details on whether any governments have committed money to the fund.

The UN decided in 2016 to set up a similar trust fund for Haiti to raise US$400 million to provide “material assistance” and treat and eliminate cholera – which killed more than 9,000 Haitians and made a further 800,000 sick. The epidemic was traced to UN peacekeepers who arrived in the country after its devastating 2010 earthquake. But as of now, the fund has secured just US$2.7 million, less than 1 percent of its target.

“Creating an unfunded trust fund to compensate victims is like giving someone an empty bank account to rebuild their life,” Rall said. “Here, as in Haiti, it is the victims of UN negligence who are stuck with the bill and who have no access to justice or remedy.”

Under international human rights law, the right to a remedy requires individual compensation to victims for material and moral damage. The UN has repeatedly committed to providing such compensation in treaties, General Assembly resolutions, and secretary-general reports. In Kosovo, however, UNMIK passed laws to try to grant itself immunity from legal and human rights complaints, even though it was Kosovo’s de facto government.

The secretary-general’s May statement promising only community assistance projects means that at best, any money paid into the fund will provide general services that do not specifically benefit the people affected by lead poisoning and will not directly offset the harm caused. The UN’s decision to set up a trust fund instead of paying affected individuals compensation and accepting its responsibility for the long-term impact of lead poisoning leaves many families struggling to care for sick relatives who were exposed to the contamination. “Nobody cares about the 12, 13 years we have suffered in the camps,” said a former leader of one camp in Cesmin Lug. “Nobody asks, ‘How is your child doing? Has he healed? Does he have any problems, any impairment?’”

Many Roma, Ashkali, and Egyptian families interviewed in northern Kosovo need financial and social support. Some parents said that they cannot afford medicine or healthy food for their affected children. Other families expressed despair about the lack of support services for children struggling at school with learning difficulties related to the lead contamination.

Samir H., a 40-year-old father of nine children who lived in contaminated camps in Zitcovac and Osterode, said: “My second-born was sent to Serbia for treatment at a hospital because his lead levels were so high…. Afterward we were told that he should take medicines to treat seizures. We had to pay for it from our money and it was hard. Today he is still very nervous.… He is not a good student because he cannot remember things…. We need to take care of him because there is no support from the school.”

Medical experts interviewed voiced concern about the lack of continuous lead testing and support for affected communities. As far as Human Rights Watch has been able to determine, recent lead testing and treatment funded by the Danish Refugee Council were limited in scope and stopped in May 2017 due to lack of available test kits.

The UN should pay individual compensation to those affected by lead contamination, allowing them to address the long-term impact of lead exposure. Parents also asked the UN to provide good health care and education to all affected children, essential services that are not available to many of the child victims. The UN should also work with the government of Kosovo and victims’ advocates to ensure that all the affected people receive adequate health care and children receive the support they need to realize their right to education.

“Kosovo, once run by the UN, is one of the places where it can make a big difference,” Rall said. “The UN should follow the recommendations of its own experts and give victims and their families the individual compensation they rightfully deserve.”

Lack of UN Accountability for Lead Poisoning in Kosovo

Timeline 1999: Roma, Ashkali, and Egyptian communities are resettled into contaminated camps by the UN 2000: Internal UNMIK report shows lead contamination in area and blood tests of population 2004: WHO conducts blood tests in camps and urges UNMIK to immediately evacuate children and pregnant women from the camps 2010: UNMIK starts moving people away from contaminated area 2013: Last camp closes 2016: Human Rights Advisory Panel releases opinion recommending that UN issues public apology and pay victims compensation May 2017: UN secretary-general announces the creation of a voluntary trust fund for community assistance projects to help “more broadly the Roma, Ashkali and Egyptian communities” – staying short of individual compensation |

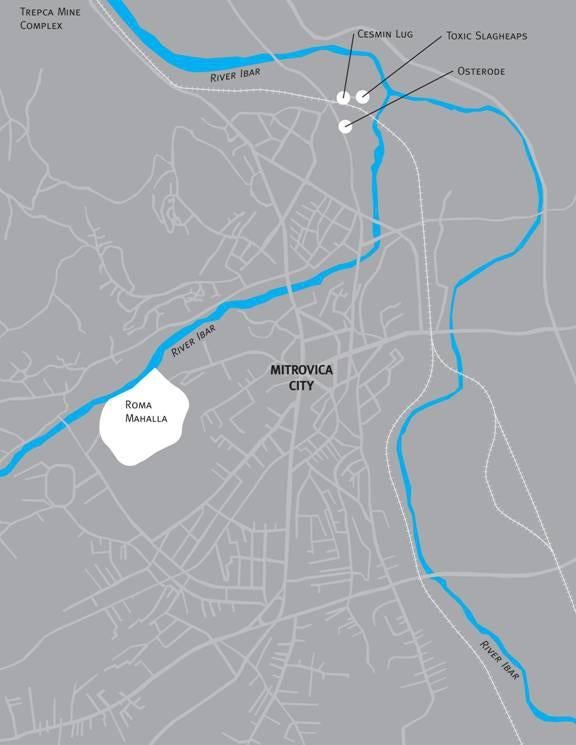

In June 1999 – after the NATO bombing of Yugoslavia ceased and the Kosovo war ended – some members of the ethnic Albanian armed group, the Kosovo Liberation Army, and civilians carried out widespread burning and looting of homes belonging to Serbs, Roma, and other minorities, including in the Roma Mahalla, the Roma district in the northern city of Mitrovica. Kosovo had just come under the control of UNMIK, the de facto civil government, and NATO forces were on the ground. The district was looted and burned to the ground. Its 8,000 inhabitants fled. Starting in September 1999, the UN resettled several hundreds of these people in two camps, Zitkovac and Cesmin Lug, in what was known to be a heavily contaminated area near a defunct lead mine.

Three additional camps were established – Leposavic in 1999, Kablare in 2001, and Osterode in 2006. The high levels of toxicity in areas surrounding the Trepca mine complex had been documented by scientific studies since the 1970s and were confirmed by an UNMIK report in 2000. In 2014, the World Health Organization (WHO) conducted blood tests in affected communities and urged UNMIK to immediately evacuate children and pregnant women from the camps. Despite these warnings, all but one of the camps were built in close proximity to the slagheaps. The camps were originally intended to be temporary, yet it took the UN more than 14 years to close the last one, in December 2013.

Starting in the early 2000s, local and international activists began to raise concerns in the media about lead poisoning and sought to force action through legal challenges. A Human Rights Watch investigation in 2009 highlighted the long-term lead exposure to which camp residents were subjected. Irrevocable damage had been done by the time the UN closed the camps.

After many attempts by the victims to seek justice and compensation, including a legal complaint filed by Dianne Post, the Human Rights Advisory Panel found in 2016 that “UNMIK was responsible for compromising irreversibly the life, health and development potential of the complainants that were born and grew as children in the camps,” including by UNMIK’s failure to relocate them to a safe environment. The panel recommended that the UN apologize and pay lead poisoning victims individual compensation. However, in May 2017, UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres’s press office announced that the UN would only create a voluntary trust fund for community assistance projects. No mention was made of any acknowledgement of responsibility or public apology.

Victims’ lawyers, Roma rights organizations, and UN accountability advocates criticized the UN’s decision not to pay individual compensation or to apologize publicly. Human Rights Watch urged Guterres to follow the advisory panel’s recommendations, both on the merits of this case and because refusing to take responsibility for the UN’s role in these abuses could undermine other UN efforts to hold member states to account for their abuses. In a June 8 letter to Guterres, former advisory panel members warned him that “at a time of backlash against human rights it is vital that the UN be seen to live up to the promise of the [UN] Charter and the obligations it has promoted.”

Long-Term Health Effects of Lead Poisoning

In June, Human Rights Watch interviewed 9 men and 10 women whose families, including more than 30 children, were affected by lead poisoning in the UN-run camps. The interviews were conducted in English or via an interpreter in Albanian or Serbian. Human Rights Watch also interviewed 10 medical providers, lawyers, and representatives of organizations providing support and services to Roma, Ashkali, and Egyptian communities. The interviews with victims took place in the Roma Mahalla, the Roma district in the city of Mitrovica, and at the homes of people who had relocated to other areas in northern Kosovo.

While the absence of consistent monitoring and testing can make it difficult to pinpoint the origin of individual illnesses, long-term effects of lead poisoning are well known. Children and pregnant women are particularly susceptible to lead poisoning. High levels of exposure in children can attack the brain and central nervous system to cause coma, convulsions, and even death. Pregnant women are at higher risk of miscarriage, stillbirth, and premature birth, and often pass on the absorbed lead to the fetus.

Symptoms can also include other physical and neurological conditions, such as anxiety, insomnia, anemia, memory loss, sudden behavioral changes, concentration difficulties, headaches, abdominal pains, fatigue, depression, hearing loss, seizures, kidney disease, and high blood pressure. The neurological and behavioral effects of lead are irreversible.

In interviews with Human Rights Watch, community members whose families formerly lived at the UN-run camps spoke about their deteriorating health. The poor and hazardous living conditions in the camps had a particularly negative impact on women and children, many of whom still experience health problems.

Sheribane M., a 45-year-old woman who lived in Zitkovac camp, said:

I have heart and kidney problems. I will get tired very quickly and need to lay down to rest a lot…. This started about three or four years ago. I tested positive for lead poisoning when we lived at the camps.

In its 2016 opinion, the UN expert panel found that women living in the camps “were subject to multiple discriminations in the enjoyments of their fundamental rights” – as women, as internally displaced people, and as members of the Roma, Ashkali, and Egyptian communities.

Several parents told Human Rights Watch that their children continued to have seizures or found it difficult to remember things at school. Samir H., a 40-year-old father of nine children, said: “Our three children who were affected by lead poisoning all have difficulties at school.”

According to WHO, no level of lead blood concentration is considered safe, and even lead levels as low as five micrograms per deciliter may result in serious health problems. The US Centers for Disease Control recommends that chelation therapy, treatment designed to remove lead from blood, should be considered when a child has a blood lead test result greater than or equal to 45 micrograms per deciliter.

“In some cases, the level of lead was so high that the measurement tool could not measure it, so above 45 micrograms per deciliter,” said Mikereme Nishliu, one of the doctors who performed lead testing in Mitrovica until 2013 for the humanitarian organization Mercy Corps. Some children tested in the camps and whose parents Human Rights Watch interviewed had lead levels higher than 65 micrograms per deciliter.

Lead poisoning victims and their parents reported that they have not been consistently examined, tested, or treated for lead-related diseases by the UN or the Kosovo government. Some of the families interviewed said that their children were only tested once at the camps and have not received any follow up testing or treatment.

Several international organizations and local service providers funded and provided small-scale testing for lead contamination and treatment by doctors and nurses several times between 2004 and 2017, focusing on children. However, children and pregnant women exposed to lead were not consistently tested over the years and the programs were discontinued due to a lack of funding or test kits. Nishliu, the doctor who performed the testing, said: “The children urgently need to be re-tested to ensure that the treatment works and that there is no new exposure.”

Victims in Need

Families of lead poisoning victims in northern Kosovo are often unable to get health care, adequate food, or other support for their children.

A 33-year-old mother who lived in the area, Elhame H., said: “If you don’t have money, the doctor will only give you the diagnosis, but you can’t buy the medication. Sometimes my husband collects paper and scrap metal to make some money. But he is also sick, so I tell him not to go. I can’t lose him.”

Some families try to get treatment in Serbia, where they believe health services are better and the medications are free. Merdjane H., a mother of six children, four of whom had lead poisoning, described the family’s problems in getting proper medical treatment: “We often do not go for exams because we cannot pay for the medicine anyway. We can get some medicine for free in Serbia but the round-trip costs €6.”

Families depending on social welfare said that they are often unable to pay for medicine for their children. Ilfete M., 69, was concerned about the health of four of her grandchildren born in the camps: “The children are not well. We try to provide good food, but we only have €170 (about US$200) for the entire month for the whole family. We need money to pay for the health care of our children.”

The long-term health effects place a particular burden on single parents. Hazbije H., a 50-year-old mother of nine, said her husband died two years ago, leaving her to care for the children alone: “Nobody is giving me any medicine for our kids. We’ve had no help with pills or injections, and nobody is helping with paying for tests. We can’t pay everything with social assistance.”

While the Kosovo government provides certain health services free, nearby health facilities in the Roma Mahalla cannot provide all the services people who have suffered from lead poisoning need, and often require patients to pay for medication. Many community members said they lived off limited social welfare or worked in low-income jobs, making it harder to pay for the services.

Muhamet I., a father of four children with lead poisoning, was disappointed that the efforts to move the communities back to the Roma Mahalla did not result in better access to health care: “There were many promises when we moved back to the Roma Mahalla. They said they would build a hospital but this never happened. We only have a small health center here, and they do not give us medicine there.”

Agnesa Jashari, a doctor employed at the Roma Mahalla health center, confirmed that the facility is not equipped to do blood exams and often lacks medication.

Several parents stated that their children had concentration problems and memory loss, causing learning difficulties. The absence of school support programs for children with lead poisoning made parents worry about their children’s chances of succeeding at school.

The lack of services and financial support often place parents in a state of emotional distress and constant worry about their children. Ali Q., 37, said his son’s lead levels in 2012 were as high as 58 micrograms per deciliter, requiring chelation therapy: “Who would leave his son like this if he could afford health care? But how can I get treatment for him without money?”

Victims Plead for Compensation and Support

Victims interviewed voiced hope that the UN will make an effort to compensate them.

Latif M., the former camp leader of Cesmin Lug, whose wife died and who cares for their five children, recalled that members of his community lived as displaced people under very difficult conditions in the camps. He believes that the UN should compensate people because it was responsible for the residents’ exposure to toxic lead: “They knew that the place was contaminated and they still built our barracks there. When they learned that the land was contaminated, they should have moved us from there much earlier ... instead of violating our rights.”

Elhame H., the 33-year-old mother with three children, said:

I want to be in a normal situation, just like everyone. My first request would be to improve the health of my children. I want them to be healthy and happy. I am not asking for much, I just want them to be healthy and happy.

The UN should work with the Kosovo government to ensure that anyone affected is tested and treated and that affected children receive the support they need to realize their right to education. The Kosovo government should make health care and medications accessible for affected families and ensure that testing and treatment of lead exposure continues. Schools in Kosovo should ensure that children affected by memory loss and concentration problems receive the support needed to realize their full right to education.

Naim M., a father of seven children, said: “I lost one of my daughters to lead poisoning and my other daughter and wife are sick now. We would need money to pay for the costs of their medical treatment.” Muhamet I., 37, hopes that his children can have a better future: “My request would be for the negotiations to continue for children to be re-tested, so that they can have better health.”