Note: This article features explainers. Click on the highlighted terms to see a short explainer.

(Moscow) – Russia has significantly expanded laws and regulations tightening control over internet infrastructure, online content, and the privacy of communications, Human Rights Watch said today. If carried out to their full restrictive potential, the new measures will severely undermine the ability of people in Russia to exercise their human rights online, including freedom of expression and freedom of access to information.

“Russian authorities’ approach to the internet rests on two pillars: control and increasing isolation from the World Wide Web,” said Hugh Williamson, Europe and Central Asia director at Human Rights Watch. “The government has built up an entire arsenal of tools to reign over information, internet users, and communications networks.”

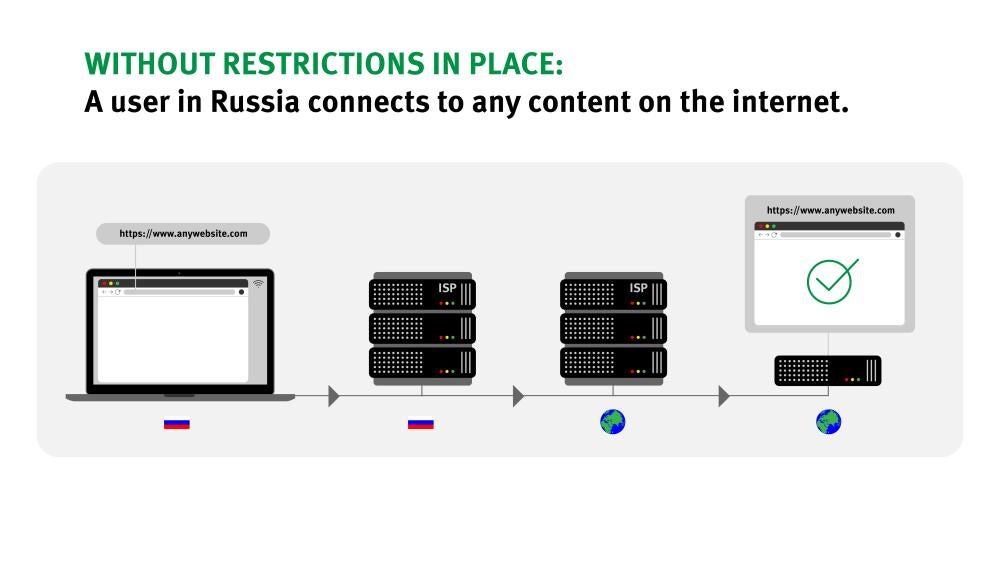

New laws and regulations adopted in the past two years expanded the authorities’ already significant capacity to filter and block internet content automatically, no longer depending on providers’ cooperation to implement the block. The 2019 “sovereign internet” law requires internet service providers (ISPs) to install equipment that allows authorities to circumvent providers and automatically block content the government has banned and reroute internet traffic themselves.

A 2018 law introduces fines for search engines providing access to proxy services, such as virtual private networks (VPNs), that allow a user access to banned content or provide instructions for gaining access to such content. Regulations adopted in 2019 require VPNs and search engine operators to promptly block access to the websites on the list maintained by the federal government’s informational system, which includes a regularly updated list of officially banned sites.

The past two years have also seen legislative incursions into the privacy of mobile communications. In July 2018, amendments to existing counterterrorism legislation entered into force that require telecommunications and internet companies registered with Russian authorities as “information dissemination organizers,” for example, messenger apps and social media, to store and share information about users without a court order.

The amendments build on previous data localization laws, which require companies processing the personal data of Russian citizens to store private data of internet and mobile app users in Russia and hand the information over to security services upon request. In 2019, Russia’s Federal Security Service (FSB) required these companies to install special equipment giving the FSB automatic access to their information systems and encryption keys to decrypt user communications without authorization through any judicial process.

Legislators have justified these rules by citing a need to protect state security, the Russian internet, and the privacy of Russian users. In reality, these requirements facilitate mass censorship and blanket surveillance, introduce non-transparent content-blocking procedures and endanger the security and confidentiality of people’s communications online, Human Rights Watch said.

These laws and regulations effectively reinforce a raft of laws adopted in previous years, and described in a 2017 Human Rights Watch report, that enable the authorities to unjustifiably ban a wide range of content.

Since 2017, the government has also increased the number of official agencies with powers to order content blocking, and increased the fines for organizations, including internet service providers, proxy services, and search engines, that refuse to take down such content or that provide means to circumvent content blocking.

The “sovereign internet” law envisages the full transfer of control over online communication networks to a government agency, from shutting down networks within certain areas of Russia, through cutting Russia off from the World Wide Web. If carried out as planned, the sovereign internet law will also enable the government to directly block whatever content it deems undesirable, Human Rights Watch said.

These internet-related requirements are embedded in an even broader set of laws and regulations aimed at stifling freedom of expression, both online and offline. Some of the recently adopted laws limit space for public debate in general, and especially on topics the government deems divisive or threatening, such as LGBT rights, political freedoms, or most recently, the Covid-19 pandemic. Other legislation apparently aims at further undermining privacy and secure communications on the internet, making no digital communication in Russia safe from government interference.

For the most part, the recently adopted laws and regulations are in their early stages of implementation or have not yet been put into effect. As a result, the manner and scope in which they will be enforced remains unclear.

The recent developments in Russian internet regulations tightening governmental control over internet infrastructure, introducing new technical means for monitoring internet activity, filtering and rerouting internet traffic, and increasing governmental capacity to block online content are inconsistent with standards on freedom of expression and privacy protected by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the European Convention on Human Rights, to which Russia is a party. While both treaties allow states to limit these rights to protect legitimate national security objectives, these limitations must be established under clear legal criteria, and the least restrictive means of achieving these objectives.

International law allows for certain restrictions on these rights such as protection of national security or of public order, health, or morals. Those restrictions, however, should be in line with the criteria of necessity, proportionality, and legal certainty. The United Nations (UN) special rapporteur on freedom of expression stated that these limits should be “provided by law, which is clear and accessible to everyone,” and be predictable and transparent. The European Convention provides that limitations imposed on freedom of expression and right to privacy should be prescribed by law and “established convincingly” to be necessary in pursuit of a legitimate goal in a democratic society.

Russia’s Constitution guarantees the right to privacy, including the privacy of communications. The Constitution also grants the freedom of opinion and the right to freely search, receive, transmit, produce, and disseminate information.

“The new laws and regulations tighten the state’s noose around users,” Williamson said. “They put users under more surveillance, yanking away their ability to access content, and threatening them with the prospect of being cut off from the outside world online.”

For detailed analysis of the new laws and regulations, please see below.

Human Rights Watch analyzed key laws and regulations that have been adopted or entered into force since 2017 and that collectively empower the Russian government to exercise extensive control over the internet infrastructure and online activity in Russia. They include:

- 2016 “Yarovaya amendments” on forced data retention;

- 2017 law prohibiting VPNs and internet anonymizers from providing access to banned websites and follow-up 2018 amendments to the Code of Administrative Offenses;

- 2017 law on identification of messaging application users and a follow-up 2018 government decree;

- 2019 “Sovereign internet” law; and

- 2019 law on pre-installed Russian applications.

Human Rights Watch also analyzed proposed implementing regulations for these laws which have not been adopted.

Forced Data Retention and the “Yarovaya” Amendments

The 2016 “Yarovaya” amendments, named after their main author, Irina Yarovaya, a member of the State Duma, the parliament’s lower house, from the ruling United Russia party, included numerous provisions that severely undermine the right to privacy and freedom of expression online. Among these were provisions that deepened the invasiveness of the troubling requirements, introduced in 2015, for tech companies to store Russian citizens’ user data on Russian territory.

Most provisions entered into force in July 2016, including the requirement for telecommunications companies to retain communications metadata for three years and for internet companies registered as “information dissemination organizers,” such as messengers, online forums, social media platforms, and any other service that enables its users to communicate with each other, to retain data for one year. Such data includes information about the time, location, and sender and recipients of messages.

Internet and telecommunications companies were also required to disclose the metadata to the authorities on demand and without a court order as well as to provide security services the “information necessary for decoding” electronic messages, such as encryption keys.

In July 2018, another batch of Yarovaya amendments came into effect, requiring companies to retain for six months the content of all communications, such as text messages, voice, data, and images, store this data on Russian servers, and make them available to the authorities on demand without judicial oversight. These provisions expanded already broad and troubling requirements to store user data of Russian citizens on Russian territory. In 2016, the government blocked LinkedIn in Russia for noncompliance with the data storage regulation. In February 2020, the government fined Twitter and Facebook four million rubles (approximately US$ 53,000) each for the same misdemeanor.

In 2019, organizations on the register of “information dissemination organizers” received letters from the FSB, requiring them to install special equipment that gives the agency around-the-clock access to their information systems and keys to decrypt user communications. The register includes 237 internet services, such as Yandex services, Telegram, the Mail.Ru Group, and Sberbank-online. The authorities have not yet compelled Google and Facebook services, including WhatsApp, to join the registry. Some of the companies have already installed the required equipment.

In May 2019, the government ordered internet service providers to store data, as prescribed by the Yarovaya amendments, using only Russia-manufactured technical means. In December, the government introduced a two-year ban on public procurements of data storage with foreign entities. In both instances, legislators interpreted the restrictions as protecting Russia’s “critical informational infrastructure.”

Banning VPN’s and Internet Anonymizers

The 2017 law on VPNs and internet anonymizers (276-FZ) does not prohibit these proxies. Rather, it aims to prevent proxy services, including VPNs and anonymizers such as Tor or Opera, from providing access to websites banned in Russia. It also prohibits search engines from providing links to such materials. The law authorizes Roskomnadzor, Russia’s federal executive authority responsible for overseeing online and media content, to block sites that provide instructions on how to circumvent government blocking, including through the use of VPNs. It also authorizes Russia’s law enforcement agencies, including the Interior Ministry and the FSB, to identify violators, and tasks Roskomnadzor with creating a special register of online resources and services prohibited in Russia.

“Laws on prohibiting VPNs and anonymizers from facilitating the bypassing of government blockings are part of the continuous expansion of governmental regulations on blockings,” Aleksander Isavnin, an IT and internet regulation expert told Human Rights Watch.

The 2017 law did not establish penalties for violations. Penalties were introduced in amendments to the Code of Administrative Offenses the following year. In April 2018, Roskomnadzor blocked millions of Internet Protocol (IP) addresses in an unsuccessful attempt to block the messaging service Telegram, for its failure to hand over user’s encryption keys to Russia’s security services, which Telegram does not hold. This led to massive disruptions, temporarily blocking services legitimately operating in Russia, such as banks, online shopping sites, and search engines. Russian internet users increasingly started using VPNs to bypass these disruptions, with some VPN providers reporting a 1,000 percent increase in sales in Russia. Roskomnadzor reacted by blocking 50 anonymizers and VPN services that provided access to Telegram.

In June 2018, the State Duma adopted a bill introducing administrative fines up to 700,000 rubles (US$ 9,000) for violations of the law on banning VPNs and internet anonymizers. The following December, Google was fined 500,000 rubles (US$ 6,500) for failing to filter its search results in accordance with the law, a precedent designed to send a signal to other companies.

In March 2019, Roskomnadzor required VPNs, anonymizers, and search engine operators to ensure that they block sites included on Roskomnadzor’s regularly updated register of banned sites through the federal government’s informational system.

Also in March, the agency published its plans to monitor compliance with the law via a more efficient automatic control system, instead of tracking blockings of banned websites manually. In June 2019, Roskomnadzor threatened to block within a month 9 out of 10 VPN services that received the order to connect to the register, for failure to comply. One service, Kaspersky Secure Connection, which also happens to be the only Russian service out of the 10 registered in the country, complied with the order. Another, Avast SecureLine, left the Russian market following Roskomnadzor’s threat.

Several VPN and internet anonymizer services still operate in Russia and provide access to websites blocked by Roskomnadzor.

Identification of Messaging Application Users

Amendments adopted in July 2017 to the law on information prohibited online messaging applications on the government’s registry of “organizers of information dissemination,” from serving unidentified users. The law requires these companies to identify all users by their cell phone numbers.

A government decree adopted in 2018 further requires foreign instant messaging service providers to sign an agreement with Russian mobile operators, obliging them to confirm a user’s identity by their phone number, within 20 minutes of the service provider’s request for the information. Messaging services cannot allow users whom mobile operators cannot identify to remain registered with the service. According to Aleksandr Zharov, former head of Roskomnadzor, the identity verification requirement applies both to already registered and new users.

The law, however, does not require instant messaging service providers registered as legal entities in Russia to confirm user identity via mobile operators, stating that such providers can use phone numbers for this purpose. The law envisaged a further decree introducing the verification rules for Russian messengers. Such a decree has not been adopted.

Under the law, Roskomnadzor can block mobile applications that fail to comply with the ban on working with anonymous accounts. It can also initiate cases under Art. 13.39 of Russia’s Administrative Code against instant messaging service providers that fail to comply with the law on identifying users. The offense is punishable by up to one million rubles (US$ 13,600) fine. Roskomnadzor has not yet initiated enforcement procedures against messaging services that don’t comply with identification regulations.

It is not clear whether foreign messaging services have been contacting mobile operators for identity verification in the two years since the regulations entered into force.

Many messaging service providers, both Russian and foreign, request users’ phone numbers for identification purposes. But some users have been able to register on messengers using SIM cards they bought unofficially, without providing the passport and other identification details they would have had to provide the official mobile operator.

Experts say that among other things, the law’s lack of clarity makes it difficult for tech companies to carry out. The 2018 decree that requires operators to sign identification agreements with messengers neither regulates the personal data transfer procedure nor explains whether mobile operators must perform this procedure for free. In addition, anonymous verification services have proliferated. These services “rent” temporary phone numbers that people can use to anonymously register with a messenger service, online platform, forum, and the like, allowing users to bypass the service’s verification. The extensive use of these services makes compliance with the law even more difficult.

The 2017 amendments also require instant messaging service providers to restrict dissemination of messages by particular users on Roskomnadzor’s demand if such messages contain information banned in Russia. In September 2017, the government drafted a decree that would establish rules to carry out this provision, but it has not been adopted. The Ministry of Economic Development criticized the draft, noting that compliance would be impossible for many messengers that use end-to-end encryption.

Parliament members acknowledged the lack of effectiveness of these regulations when the State Duma considered a similar legislative initiative for email service providers. The initiative has not advanced in parliament, and the government has not taken any further steps to enforce the law or impose sanctions for offenders.

If fully enforced, however, these regulations will jeopardize the confidentiality of information and communications by Russian internet users.

The Sovereign Internet Law

In May 2019, President Vladimir Putin signed the “sovereign internet” law, whose proclaimed goal is to protect the Russian segment of the Internet from threats to its security, integrity, and sustainability. In reality, the law further expands the state’s control over internet infrastructure.

The part of the law that entered into force in November 2019 obliged internet service providers (ISPs) to install “the technological means [equipment] for countering [external] threats” into their networks. This equipment includes deep packet inspection (DPI) technology, which allows the government to track, filter, and reroute internet traffic. Experts have criticized this technology as instruments of censorship and surveillance.

Deep Packet Inspection

By mid-November 2019, some of the Russian internet service providers had installed and tested the equipment in the Urals and reported partially successful results to the Communications Ministry. Three out of eight operators reported no problems with internet traffic, whereas five others reported a range of problems, including slower internet speed, weaker signals, continued failure to block the Telegram messenger, and local disruption of internet services. Operators noted that due to the low number of users in the region chosen for running tests, it was not possible to evaluate the work of the DPI technology when dealing with large volumes of internet traffic.

According to the law, this technology should prevent users from accessing any content the authorities deem unwanted by using direct commands, which the authorities have programmed, without the users or ISPs even noticing.

The Russian government has long been criticized for excessive blocking of internet access and for using internet regulations for censorship. Even without DPI technology fully functioning, at least 85,246 websites have already been blocked as of June 10, 2020. In this context, both local and international human rights organizations expressed concerns over the nontransparent and extrajudicial blocking of websites facilitated by the deep packet inspection technology.

Who orders content blockings in Russia?

Authorized body | Number of sources blocked in 2020* | Reasons for which they are authorized to block |

Federal Service for Supervision of Communications, Information Technology and Mass Media | 3,038 | Information on child pornography |

Federal Service on Surveillance and Consumer Rights Protection | 358 | Information on ways of committing suicide |

Ministry of Internal Affairs | 4,211 | Information in breach of drug regulations |

General Prosecutor | 6,874 | Information containing calls for mass riots, extremist activity and participation in breach with law’s requirements. |

Federal Tax Service | 34,950 | Information violating legislation on gambling and lotteries |

The Ministry of Communications and Mass Media | 3,712 | Websites copying sources previously blocked for the breach of copyrights. |

Russian Federal Service for Alcohol Market Regulation | 948 | Information violating regulations on alcohol |

Federal Agency for Youth Affairs | 8 | Information aiming at involving minors into unlawful activity or spreading information about survivors of such activities |

Moscow City Court | 10,673 | Illegal copies of content protected by intellectual property laws |

Other courts | 21,035 | Information dissemination of which is deemed forbidden in Russia based on the court’s judgment |

* According to the data by Roskomsvoboda, retrieved on 6/10/2020

In March 2020, the General Radiofrequency Center, administered by Roskomnadzor, commissioned a study from the Russian Academy of Sciences on the techniques widely used to bypass governmental blocks in Russia, such as VPNs and other proxies, like Tor and Telegram Open Network. This study aims to provide the government with more effective tools for filtering internet traffic.

National Domain System

The “sovereign internet” law also requires the creation of a national domain domain name system (DNS). Beginning January 1, 2021, internet service providers will be required to use the national DNS. The DNS works as the address book of the internet, translating a URL address into a numerical IP address, which is then used to connect a user to the website they are looking for. Forcing ISPs to use the national domain name system would allow Russian authorities to manipulate the results provided to the internet service provider, which would enable the authorities, among other things, to substitute the user’s request with the wrong website address or no address at all.

More State Control Over Internet Architecture

The sovereign internet law further expands governmental control over the RuNet infrastructure, obliging its actors to provide Roskomnadzor detailed information about their “network architecture.” Russian authorities can use this information to increase control over them.

The law gives the government all the information on the internet infrastructure it would need to exercise complete and unchecked control over the internet, resulting in violations of freedom of expression, access to information, and privacy, Human Rights Watch said.

For example, internet service providers registered in Russia must provide information about where internet traffic goes outside of Russia. This could allow the authorities to reroute traffic through deep packet inspection technology.

According to the law, operators of internet exchange points (IXPs), key hubs for internet traffic exchange, are required to disconnect internet service providers that do not comply with the law’s requirements. The breach of this requirement by an exchange point might lead to their exclusion from the official registry. This, in turn, would ban ISPs from connecting to it.

Although the government provides internet service providers with the deep packet technology equipment free, providers incur considerable costs to ensure that it works properly.

“The state’s interference with the relationship between internet service providers appears to be the most dangerous aspect of the law, potentially affecting the competition in the market and causing a lot of smaller ISPs to leave,” Isavnin told Human Rights Watch. “The variety of internet actors and connections between them is what actually ensures internet security.”

Bylaws adopted that further carry out the “sovereign internet” law identify general threats to the resilience, security, and integrity of the RuNet as legal grounds for activating the “centralized state management of the internet.” This protocol entails the full transfer of control over communication networks to Roskomnadzor, from shutting down networks within certain areas of Russia, up through cutting Russia off from the World Wide Web if needed. These provisions are of special concern taking into consideration several occasions, when the Russian government has allegedly temporarily turned off mobile internet services, including during protests in Moscow and Ingushetia.

“The sovereign internet law could be a very effective [suppression tool in the hands of the government],” Andrei Soldatov, a Russian investigative journalist and expert on Russian surveillance, told Human Rights Watch. “The law’s idea is not to isolate the country completely, but to have a tool to isolate regions if they face a crisis. This can be very effective, and this is what we saw in Ingushetia for almost a year and a half, with protests over a land dispute with Chechnya. Blackouts were used to prevent the protests to spill over to other regions.”

At the same time, the “sovereign internet” law provides the Russian government with a tool for fully enforcing its restrictive internet- and communications-related legislation and deepens the restrictions on digital rights even further.

The Law on Pre-Installed Russian Apps

In December 2019, parliament adopted amendments to Russia’s consumer protection law that oblige manufacturers to pre-install Russian apps on certain types of devices sold in Russia. Legislators said the initiative aimed at enhancing Russian users’ convenience, offering them apps oriented at Russian speakers, as well as at promoting domestic software.

Under the latest draft decree developed by the government as a follow-up to the law, all smart phone, computer, and Smart TV manufacturers operating in Russia will be obliged to pre-install software that meets certain criteria, including “high social importance,” exclusive rights ownership by the Russian company or person, and full compliance with personal data protection regulations for at least one year prior to installing them. The types of apps eligible for pre-installation include messengers, browsing services, maps, news readers, and email providers. The Federal Antimonopoly Service (FAS) will be tasked with supervising the list of applications that meet these criteria.

“There is no doubt the state will use this opportunity in its interests,” Isavnin told Human Rights Watch. “There is a risk that surveillance apps and traffic decryption certificates would be installed.”

The law on pre-installation provides the Russian government with effective leverage on domestic application software developers. Pre-installing apps on users’ devices would most likely increase their prominence on the Russian market, thus creating economic incentives for the developers to comply with laws on user data localization and retention of user data. Compliance with these requirements is obligatory for pre-installation. In July 2019, a draft law was introduced in parliament proposing fines of up to 200,000 rubles (US$ 2,700) for selling devices with no pre-installed Russian apps. The law still has not passed the first hearing.

“The idea is to make Russian customers use Russian developers’ applications, which can be more easily controlled than foreign apps,” said Soldatov.

Russia’s Media and Communications Union, encompassing the largest mobile operators and media holding companies, has already proposed requiring that all types of pre-installed apps verify users’ identity, probably inspired by the recent law on identification of messaging application users.

The law was initially scheduled to enter into force in July. However, in light of the Covid-19 pandemic, the date was pushed to January 1, 2021.