(Bangkok, June 10, 2020) – Malaysia’s new administration is increasingly using abusive laws to investigate and prosecute speech critical of the government, Human Rights Watch said today. Since the Perikatan Nasional coalition took over the federal government in early March 2020, the authorities have sharply heightened investigations of individuals under broadly worded laws that violate the right to freedom of expression.

“Like flicking a light switch, Malaysian authorities have returned to rights-abusing practices of the past, calling journalists, activists, and opposition figures into police stations to be questioned about their writing and social media posts,” said Phil Robertson, deputy Asia director at Human Rights Watch. “The government should stop trying to return to the bad old days and revise the laws to meet international standards.”

Those investigated in recent months include journalist Tashny Sukumaran, who faced police questioning after she reported on immigration raids in an area under an enhanced movement control order due to the presence of Covid-19. Cynthia Gabriel, the founding director of the Center to Combat Corruption and Cronyism (C4 Center), had been called in for police questioning about a letter calling for an investigation into allegations that the government was trading favors for political support. On May 20, the police summoned an opposition member of parliament, Xavier Jayakumar, for questioning after he criticized the government’s decision to limit the recent sitting of Parliament to a speech by the king.

On May 8, prosecutors charged a businessman with violating section 233(1) of the Communications and Multimedia Act (CMA) and section 505(b) of the Penal Code for social media comments criticizing the government for prosecuting individuals who violated the movement restrictions put in place due to Covid-19. On June 5, prosecutors charged R. Sri Sanjeevan, the head of the Malaysian Crime Watch Task Force, with two counts of violating section 233(1) of the CMA for allegedly posting “false” information about the police on social media.

All of the laws cited in these investigations are overly broad and subject to abuse, and all have been used by prior administrations against critical voices, Human Rights Watch said. Section 233(1) of the CMA makes it an offense to make an online communication that is “indecent, obscene, false, menacing or offense in character with intent to annoy, abuse, threaten or harass any person,” and carries a penalty of up to one year in jail and a RM50,000 (US$11,695.00) fine.

Section 504 of the Penal Code, one of the laws cited in the Sukumaran investigation, provides for up to two years in prison for anyone who “intentionally insults ... any person, intending or knowing it to be likely that such provocation will cause him to break the public peace.” Section 505(b) of the Penal Code makes it an offense punishable by up to two years in prison to make, publish, or circulate “any statement, rumor or report with intent to cause, or which is likely to cause, fear or alarm to the public, or to any section of the public, whereby any person may be induced to commit an offense against the state or against public tranquillity.”

Minister of Communications and Multimedia Saifuddin Abdullah responded to Sukumaran on Twitter on May 3, stating that he had instructed the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission not to charge her. However, neither the minister nor the government has made a commitment to reform the Communications and Multimedia Act.

Under international human rights standards, governments may only impose restrictions on freedom of expression if they are provided by law and are necessary for the respect of the rights or reputations of others, or for the protection of national security, public order, public health, or morals. Restrictions must be narrowly drawn to limit speech as little as possible, and sufficiently precise that an individual can understand what is made unlawful. None of the laws at issue meet these standards, Human Rights Watch said.

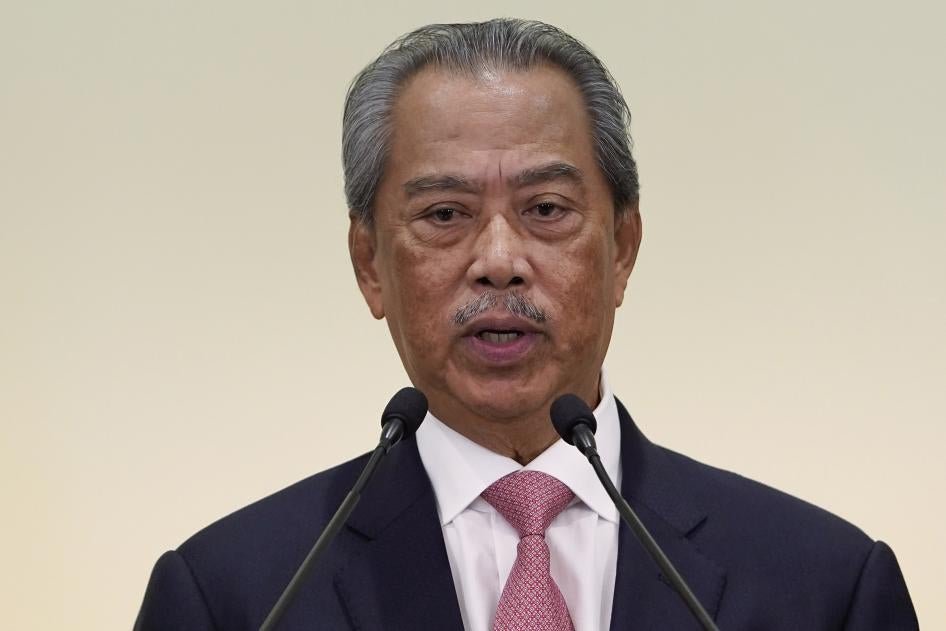

“Malaysians should be able to criticize their government and its policies without fear of facing police questioning and possible criminal charges,” Robertson said. “Instead of dusting off abusive laws for use against its critics, Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin’s administration should amend or repeal those laws to protect everyone’s freedom of speech in Malaysia.”