Public health experts say that the main way to protect yourself from COVID-19 is to socially distance yourself from others, isolate those who become ill and wash your hands frequently with soap and water. In camps for internally displaced people or refugees, where so many people seek shelter and protection in armed conflicts or humanitarian crises, this is nearly impossible. Few can afford soap, clean water is rare and social distancing unrealistic. Trust me, I know.

I also know first-hand that it’s even more difficult for people like me: people with disabilities.

In 2015, I arrived in a refugee camp on the island of Lesbos in Greece after fleeing the war in Syria. I couldn't get water to wash my hands; the tap was just too high for someone in a wheelchair. The toilets weren’t accessible either. Some days, I had to hold my bladder for hours to avoid having to use a toilet.

A year later, I met some Human Rights Watch researchers who were documenting the situation for refugees, asylum seekers, and migrants with disabilities in refugee camps in Greece. They told me about Ali, a 22-year-old asylum seeker from Afghanistan. For two months, the only place where he could take a bath was in the sea, simply because the few showers in the Moria refugee camp on Lesbos were not accessible to him or other wheelchair users like him. As these places have become even more overcrowded, with Moria currently holding more than 19,000 people in a place designed for fewer than 3,000, the situation has only grown worse.

In some humanitarian crises, such as in the Central African Republic and South Sudan, Human Rights Watch documented that, without ramps, bars or other supports, some people with physical disabilities have to crawl to enter toilets. Can you just imagine what that feels like? I can. And with COVID-19 spreading across borders without control, this is not only an affront to dignity, it also carries huge, potentially life-threatening, health risks.

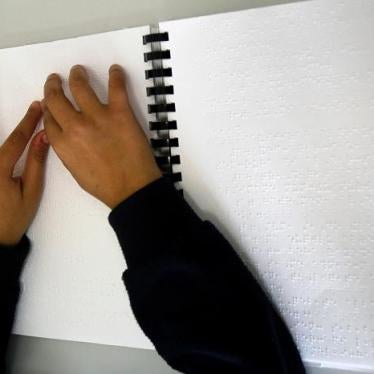

Hygiene is one key element of maintaining good health, and so is good information. People with disabilities living in camps for refugees and displaced people need information in a way that works for them. I worry about how people who are blind or deaf can get information about how to protect themselves from COVID-19. Is the information about this global pandemic presented in a way that makes sense for someone with an intellectual disability? I hope so, but I’m afraid not.

Last week, the UN released a COVID-19 Global Humanitarian Response Plan, and promised to address the needs of people most at risk, including older people, people with disabilities or chronic illness, women and children.

This is a great commitment, but I hope this is more than just lofty words on paper. What I’ve seen firsthand is that with governments, donors, and aid agencies overwhelmed with many competing priorities during serial humanitarian crises, the needs and concerns of people with disabilities are often overlooked.

Any government or aid agency’s response to COVID-19 should be planned and carried out in close consultation with people with disabilities and older people. People with disabilities, like myself, know best what risks we face and what we need. And COVID-19 testing and treatment needs to be accessible to people with disabilities.

When installing handwashing stations and sanitation facilities in camps, governments and humanitarian organisations also should ensure they are accessible to everyone. Finally, information on protection from the virus and information on how to get testing and treatment needs to be accessible to people with different types of disabilities and older people.

Nearly one year ago, I briefed the UN Security Council on the situation of people with disabilities in Syria. All 15 members of the Council nodded in agreement when I said: “This should not be just another meeting where we make grand statements and then move on…you can and should do more to ensure that people with disabilities are included in all aspects of your work – we cannot wait any longer.”

Security Council members vowed to do their best to make sure that the needs of people with disabilities were part in the humanitarian response in Syria and beyond. Now that the world is trying to defeat COVID-19, here’s your chance to make good on that promise. Again, this is a matter of life and death.