For the first time in more than 14 years, the Sudanese government last month welcomed a Human Rights Watch delegation, which I headed, for official meetings in Khartoum. This remarkable turn-around signals a new openness after protesters forced longtime dictator and indicted war criminal Omar al-Bashir to step down last April. Ongoing pressure from protesters has compelled the military and its paramilitary allies to permit a significant degree of civilian rule.

There is an exhilarating air of hope in Khartoum that a rights-respecting democracy can be built. But powerful forces are resisting, as illustrated by the attempted assassination of the civilian prime minister, Abdalla Hamdok, on March 9. (The identity of the attackers is still unknown.) Rapid international support is needed to avoid squandering this rare opportunity for democracy in the country.

Sudan has made a great deal of progress in the past year. Thanks to the Sudanese population’s resistance to any return to military rule, military leaders agreed in July to share power with civilians. The military is chairing a ruling sovereign council—effectively a collective presidency—for the first 21 months, to be followed by civilians for the next 18 months, after which elections are supposed to be held. The leaders appointed a civilian prime minister, selected civilian ministers, and agreed on a time frame for appointing a legislative council, regional governors, and various commissions to carry out the prodigious task of reforming the government after 30 years of mismanagement, corruption, repression, and violent abuse.

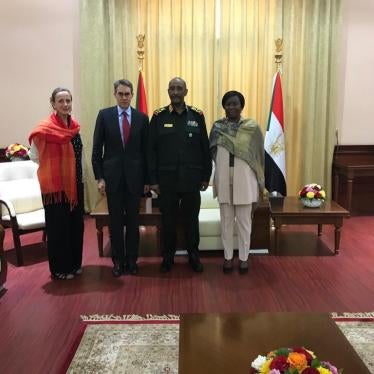

The senior officials I met with went out of their way to profess their commitment to democratic reform. The chair of the sovereign council, Lt. Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, and Prime Minister Hamdok reiterated their desire to enhance respect for human rights and the rule of law, including cooperating with the International Criminal Court (ICC), which has issued arrest warrants for Bashir and four others for directing atrocities in Sudan’s western province of Darfur. This was a remarkable shift after years in which Bashir refused to recognize the court.

Justice Minister Nasredeen Abdulbari, who was educated at Georgetown University in Washington, is churning out new laws, suspended discriminatory public-order laws, and has banned flogging, a form of corporal punishment that flouts international human rights law. Attorney General Taj al-Sir al-Hebr has set up committees to investigate the most serious past atrocities, important steps that should complement the work of the ICC.

As called for in last summer’s agreement, the government also began an investigation into the killing of at least 120 unarmed protesters on June 3, weeks after Bashir was ousted. The investigating committee has a tough task because those behind that violent crackdown included the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF). Once known as the Janjaweed, the RSF was responsible for mass atrocities in Darfur as well as Southern Kordofan and Blue Nile states. It is led by Lt. Gen. Mohamed Hamdan Dagolo, known as “Hemeti,” who is Burhan’s deputy on the ruling sovereign council. The RSF is the most powerful armed group in the country.

But instead of facing criminal charges for his past crimes anytime soon, the wily Hemeti has made himself arguably the country’s most powerful leader. He is being touted by some Sudanese political leaders, including certain opposition politicians who have long called for justice for abuses in Darfur, as a reliable strongman and a bulwark against radical Islamists. Such countervailing pressures—to fight Islamists while keeping stability in the security sector at the expense of justice and accountability—help explain some of the fragilities in Sudan’s transition and why supporting civilian leadership and oversight of security forces is so urgent.

Already there are worrisome delays. The government has not yet appointed the legislative council and civilian governors. One excuse offered is the need to wait for Darfur peace talks to be concluded so rebel groups can then be represented in the legislature, though the talks are proceeding slowly. A better approach would be to establish the much-needed legislature now and reserve certain seats for rebel groups to be filled once the peace talks are concluded. The government has also not yet formed promised commissions for human rights, transitional justice, and elections, among others, or made meaningful institutional reforms.

The transition has not reached Darfur, where civilians are still at risk of attacks. Fighting between Arab and Massalit communities in West Darfur in December led to a large attack by armed Arab militia, including members of the RSF, on the Krinding displaced persons’ camp. Dozens of people were reportedly killed, homes were burned, and tens of thousands were forced to flee. A United Nations-African Union peacekeeping mission, UNAMID, which might have helped to de-escalate the situation, had left the area in May. Both the government and the U.N. seem intent on winding down UNAMID by October despite the lack of any alternative force to curtail such violence.

Perhaps the most pressing of Sudan’s challenges is its economy, which lies in tatters after years of the former government’s corruption, mismanagement, and overspending on military and security sectors. Inflation has soared, and the price of crude oil, the main revenue earner, is down. I saw long fuel and bread lines in Khartoum. Because bread prices were a major trigger for the December 2018 protests that toppled Bashir’s government, the transitional administration needs a quick fix.

But donors do not appear to be stepping up. Some are waiting for Sudan’s leaders to articulate their economic strategy, especially for lifting subsidies on basic products such as bread and fuel, despite the enormous unpopularity of such moves. Others are reluctant, fearing that military and paramilitary leaders will find some way to scuttle the democratic transition.

This delay in responding to Sudan’s economic crisis raises the possibility of a stillborn transition. The lack of funds, among other things, is impeding the work of the justice minister and the attorney general and the all-important investigation into the June 3 massacre. There needs to be a way to support civilian officials—reinforcing their popular legitimacy—without bolstering military and paramilitary forces.

Sudan’s government and some civil society groups have pressed the U.S. government to lift its designation of Sudan as a state sponsor of terrorism (SST), which keeps trade sanctions in place, restricts international loans, and discourages foreign investment. They argue that keeping SST and related sanctions could undermine a democratic transition.

Human Rights Watch doesn’t take a position on whether states should be designated sponsors of terrorism. But when the Obama administration announced it would take steps to lift comprehensive economic sanctions imposed on Sudan during the Bashir regime, we insisted that certain human rights benchmarks be met before such relief was made permanent. We also urged Washington to impose individual, targeted sanctions against those implicated in grave violations.

Much has changed in Sudan since then, but in setting policy toward Sudan, the U.S. government should still be guided by clear and transparent human rights benchmarks with the goal of helping civilian authorities build a rights-respecting government, assert the rule of law over security forces, and fulfill the social and economic rights of the Sudanese people that the Bashir government eviscerated.

That means helping the new government achieve an ambitious reform agenda, ensuring a transition to civilian rule, and securing accountability for those who directed the most serious abuses, including against protesters. Promoting such accountability is best pursued through individual, targeted sanctions, rather than broad economic ones, by sidelining obstructive actors rather than treating them as respected interlocutors and by urging Gulf states to discontinue their support for these individuals. The overriding aim should be to help the Sudanese people in their quest for a more transparent and accountable government based on the rule of law.

The civilian leaders I met in Khartoum were impressive and seemingly committed to a successful democratic transition. But as they face a dire economy and recalcitrant security forces, their window of opportunity is narrow. The West should attach the highest priority to helping them navigate the new but treacherous path to a rights-respecting government in Sudan.