(Bamako) – An ethnic militia in Mali massacred over 35 villagers on February 14, 2020 after government troops left the area, Human Rights Watch said today. The killings in the village of Ogossagou occurred hours after village leaders alerted government officials that the Malian army had vacated a post created following the March 23, 2019 massacre of 150 people in the same village, and an hour after a United Nations peacekeeper convoy had passed through.

Armed ethnic Dogon men chased civilians into the bush and killed them, decapitating and mutilating some, witnesses told Human Rights Watch. Most victims were ethnic Peuhl men from the village. An elderly Peuhl woman and four children were also killed, and 19 villagers remain unaccounted for. Witnesses gave Human Rights Watch the names of 20 Dogon men who witnesses recognized as being among the attackers, most from Ogossagou’s Dogon neighborhood, including some who had allegedly participated in the March 2019 killings.

“Ethnic militias who apparently have no fear of being held to account have once again murdered and mutilated dozens of civilians,” said Corinne Dufka, Sahel director at Human Rights Watch. “The second massacre in Ogossagou was especially horrendous because the Malian army and UN peacekeepers might have prevented it.”

Human Rights Watch interviewed 18 people in Mali in February and March, including 10 witnesses to the attack, Peuhl community leaders, Malian justice and security officials, and foreign diplomats. In response to letters from Human Rights Watch, the government, in letters from two ministries, Defense and Veterans Affairs and Justice and Human Rights, said a “tactical error” led to the massacre, and that disciplinary measures were immediately taken, pending investigations which were being conducted. The UN mission said an investigation into the Ogossagou incident was underway.

On February 13, Malian army soldiers withdrew from their post in Ogossagou without providing an explanation to the Peuhl villagers. Within hours, they observed a build-up of armed men in the Dogon neighborhood. Ogossagou villagers and Peuhl community leaders in Bamako, the capital, said they made numerous frantic calls to high-level Malian authorities, including several ministers, and to the UN peacekeeping mission, MINUSMA, warning of an imminent attack. A convoy of UN peacekeepers passed through the village an hour before the attack, apparently looking for the village of Ogossagou, but left after Dogon men apparently misdirected them, witnesses said.

Shortly after 5 a.m. on February 14, the attack began. “They searched through the bush, looking for people to kill,” a witness said. “They found my friend meters from where I was hiding … they dragged him out, shot him, and then mutilated his body.” Another witness said, “I saw them pull Bocarie, 47 years old, out of a house. ‘Please, in the name of God, don’t kill me!’ he said, but they slashed him with a machete and cut his throat.”

The killing only stopped three hours later, after Malian troops and UN peacekeepers arrived on the scene. One assailant was apprehended but the rest fled.

Ogossagou residents expressed outrage at the lack of protection and the lack of justice for the earlier massacre. “If those who killed in 2019 were put in jail, this second attack wouldn’t have happened,” a witness said. “What do I say to a woman who lost two children in last year’s attack, and her only remaining child in this one?” asked an elder.

Deadly incidents of communal violence in central Mali have risen steadily since 2015, when Islamist armed groups moved from northern into central Mali. The violence has pitted ethnic self-defense groups from the agrarian Bambara and Dogon communities, which formed in response to the inadequate presence of state security forces, against mainly nomadic Peuhl or Fulani communities, which have been accused of supporting the armed Islamists.

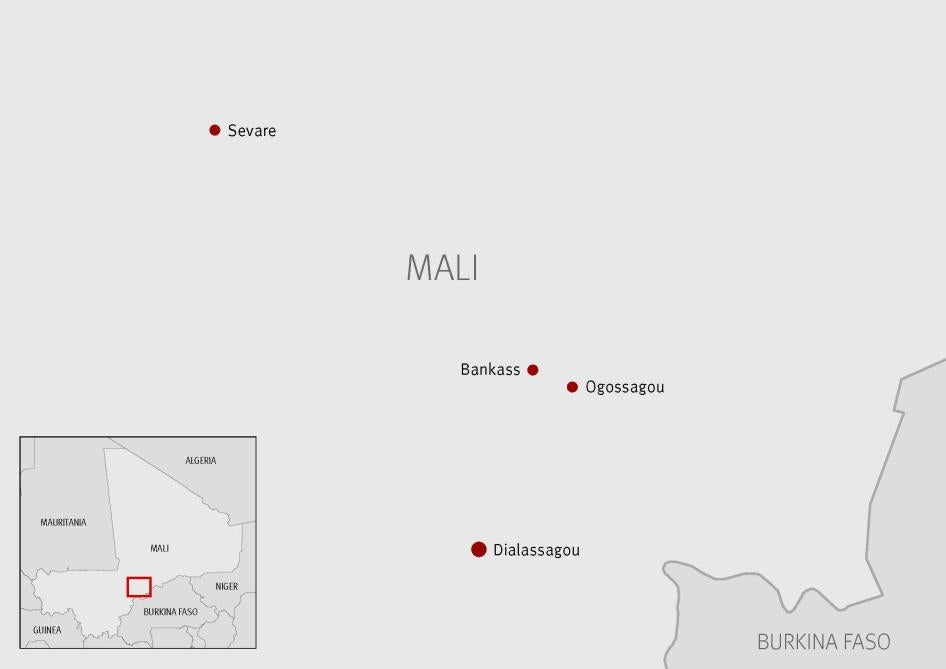

Since 2015, Human Rights Watch has documented the killing of over 800 civilians in central Mali in dozens of large-scale massacres of Peuhl civilians by Dogon and Bambara militias, as well as numerous killings, including massacres, of civilians by armed Peuhl men and Islamist armed groups. The epicenter of the violence is in Mopti region, and Bankass cercle, the administrative area where Ogossagou is located, has been particularly hard hit since 2019 with scores of reprisal killings of farmers and herders from all ethnic groups.

Malian authorities should urgently arrest and appropriately prosecute those responsible for the February 14 massacre, including those who planned and orchestrated the attack, Human Rights Watch said. The authorities should disarm all abusive militias, including in Ogossagou, and resettle vulnerable residents who want to leave the village.

“The Malian authorities and parliament as well as the United Nations should investigate the role of the Malian army and UN peacekeepers, and take appropriate disciplinary action against anyone who was negligent in their duty to protect civilians in Ogossagou,” Dufka said.

Army Withdrawal on February 13

Ogossagou village is 15 kilometers south of the administrative headquarters of Bankass and has over one thousand inhabitants. The Peuhl and Dogon residents live in separate neighborhoods, 300 meters apart. In the aftermath of the March 2019 massacre, and given ongoing communal tension, a military post of about 40 soldiers from the Malian Armed Forces (FAMA) was established in Ogossagou to deter any further violence between the Peuhl and Dogon communities. The presence of the soldiers had reassured the Peuhl population from Ogossagou and several other Peuhl villages whose inhabitants had flooded into Ogossagou for protection after their own villages had come under attack by Dogon militias in 2018 and 2019.

“Last year, when the president came to Ogossagou to offer condolences for the 2019 massacre, he promised the FAMA would remain here to protect us,” a village elder said. “I recall IBK [President Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta] saying, ‘Even if it takes 10 years for peace to return, they will remain.’ It was because of that promise that we stayed.” Another resident echoed the sentiments of the villagers interviewed: “We thought we were safe; the government promised it would never happen again.”

Peuhl villagers described their confusion when, beginning at about 3 p.m. on February 13, they observed the Malian army taking down their tents and loading up their vehicles without notifying the community. “We thought they were changing guard, that other soldiers would be replacing them,” a resident said. “They couldn’t possibly leave without informing us, but they did.”

“From the moment they started packing up – and we saw no one was replacing them – we started raising the alarm,” another resident said. “I was with the village chief when he called several people in Mopti and Bamako to tell them the soldiers were abandoning the village and that we were terrified of being attacked.”

Villagers said the soldiers were well aware of ongoing deadly incidents. Fifteen Peuhl villagers who had ventured out of Ogossagou had been killed in recent months, a village elder said. He said that in early February, three Peuhl shepherds, including a 14-year-old boy, had been killed less than a kilometer from the village, allegedly by their armed Dogon neighbors.

The mother of one of the victims said, “My last-born son and two other youth left at 6 a.m. to gather food for our animals. A few hours later, we heard gunshots. My heart sank. When they didn’t return, we asked the FAMA to search for them. Later, they brought their bodies on a donkey cart for burial.”

Eight witnesses said that beginning at about 7 p.m. on February 13, they noticed armed men arriving in Ogossagou’s Dogon neighborhood on motorcycles, motorized taxis, and at least one car, indicating, to them, that an attack was being prepared. They said in the early hours of February 14, residents noticed motorcycle headlights in several places around the village, suggesting that armed men were, as one witness said, “getting in position like they did before the first [March] attack.”

“As soon as the FAMA left, I said, ‘Tomorrow will not find us alive,’” a 58-year-old woman whose husband was wounded in the attack told Human Rights Watch. “From shortly after the FAMA pulled out and throughout the night we saw the headlights of motorcycles going into the Dogon neighborhood.”

An elder told Human Rights Watch: “No one slept that night. Many villagers decided to flee under cover of night, while those who remained in the village waited by the door, praying God would save them. As the first shots rang out, just after 5 a.m., we ran into the forest, amid the sound of gunfire and screaming and chaos.”

February 14 Attack

“A gunshot, signaling the beginning of the attack, was heard immediately after the early morning call for prayer on February 14,” said the 58-year-old woman.

Scores of Dogon-speaking men armed with military assault weapons and hunting rifles stormed Ogossagou village and chased those fleeing into surrounding areas. Three hours later, at about 8 a.m., Malian security forces and peacekeepers from the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) arrived and dispersed the attackers. The Malian security forces exchanged fire with the attackers, killing several, and apprehended one, who remains in custody. In addition to killing several dozen civilians, the attackers also burned scores of houses and granaries and looted 700 animals, including cows, goats, sheep, and donkeys, and other valuables.

“The Dogon had surrounded the village and fired at us as we ran and at people who’d scrambled up trees to hide,” said a villager. “Last time, they massacred villagers in the houses, but this time most people were killed in the bush.”

Two men described the killing and decapitation of 26-year-old Allaye Barry. One said:

We’d hidden in the bush, curled up, trying to avoid detection. Around 7 a.m., a large group of attackers passed by, and then stopped about 50 meters away. I recognized many of them including Dogon men I’d grown up with; most were armed with automatic rifles. As they searched for us, my heart raced. They found Allaye, around 10 meters away from me. They shot him point blank, then decapitated him and put his head in a sack. Minutes later, one of the attackers yelled that the FAMA were coming and ordered the others to break into three smaller groups and retreat.

Two residents saw an attacker fire a hunting rifle at two children, ages 9 and 14, wounding both. “They yelled at the children, who were curled up under a shrub, to ‘Get up, now!’ and immediately opened fire,” one witness said. “The children fell down, bleeding. The mother of one of the children was hiding nearby and as the attackers left, she yelled at her daughter to drag herself back into the bush to hide until the attack was over.”

A few villagers said some attackers appeared to spare women and children. One woman said:

The women and children, including myself, had gathered in anticipation of the attack and when it started, we fled east, and the men went to the west. As I ran, two Dozos [traditional hunters] caught me, and one said, “Kill her, kill her.” But the other said, “No, they are women.” The men were hunted down in the bush… Honestly, I didn’t see any of the men who went west alive after the attack.”

A 55-year-old woman said:

Five women and seven of our children huddled together in a house under heavy gunfire when four Dogon, all armed with AKs [military assault rifles], forced their way through the door and ordered us out saying, “We’re killing all of you.” I said…trembling, “Please, have mercy on us…What will it serve you to kill us?” They searched the house for men and threatened to kill the only boy child, who was around 9 years old, but eventually they left us. As we fled, they set the house on fire, and looted everything, including our sheep, which they untied and took away with them.

Retrieval of Bodies, Burials

On the basis of interviews with family members of victims, witnesses, and those who buried the dead, Human Rights Watch estimates that 36 residents, including 4 children, were killed in the Ogossagou massacre, while 19 others, including 3 children, remain missing.

“The majority of the dead were men,” a village elder said. “We were finding the dead for several days: most scattered here and there in the bush, some up to two kilometers away. Several of those killed were displaced from other villages, including the chief of Guiwagou village.”

A man who participated in the search, retrieval, and burial of bodies described finding his 27-year-old son among the dead:

After the gunfire stopped, I couldn’t find my first-born son but had hope in my heart he’d survived. About a kilometer north of the village we came upon two bodies … they’d been peppered with gunfire … my heart sank when I recognized my boy. We found 21 bodies the first day – one here, two there – and seven more the following day.

Another man who helped retrieve the dead said he’d buried three people who had been decapitated, an elderly woman who had been burned in her house, and a father and his 2-year-old daughter.

Alleged Perpetrators

The 10 witnesses to the attack who spoke to Human Rights Watch said the attackers were armed Dogon men who they alternatively called “Dozos,” “hunters,” “Dogon militiamen,” or members of Dan Na Ambassagou (meaning “hunters who trust in god” in Dogon), an umbrella group of Dogon village self-defense groups with a quasi-military structure.

The witnesses said most of the attackers were dressed in attire traditionally worn by the Dozos: reddish-brown clothing adorned with amulets, such as shells or mirrors, and some wearing caps with small animal horns. Some attackers were dressed in civilian attire. Witnesses also provided Human Rights Watch with the names of 20 alleged assailants whom they said they recognized, most of them from the Dogon neighborhood of Ogossagou.

Two Malian officials with knowledge of the government’s investigation into the February 14 attack told Human Rights Watch that a local Dan Na Ambassagou commander is suspected to be responsible for planning, organizing, and distributing the ammunition used in the attack. As far as Human Rights Watch has been able to determine, the authorities have yet to question him.

On February 15, Dan Na Ambassagou issued a statement denying responsibility for the attack. Two Dogon men from Ogossagou told Human Rights Watch that members of their community were not involved in the attack. They said the attackers were “unidentified assailants.” They said tensions between the Dogon and Peuhl communities were high, noting that in January, two Dogon men from Ogossagou village had been killed three kilometers away by “armed Peuhl men” as they collected grass for their animals to eat. They also said armed Peuhl men from the area had, in January, stolen hundreds of their animals.

Three witnesses to the February 14 attack said they had identified a few armed Dogon men who had also participated in the 2019 massacre. “They were in the first attack – I saw them,” one said. “I named them to gendarmes investigating the 2019 attack, and again to gendarmes who investigated the 2020 attack.”

Attempts to Alert Malian Security Forces

Three community leaders from Ogossagou said that beginning at about 3 p.m. on February 13, they had made frantic telephone calls to military, security, and government representatives, and to MINUSMA, to express their concern about the departure of army personnel, and, later, after observing the movement of armed Dogon men into the village, their fears of an imminent attack.

The leaders said that they repeatedly appealed for the urgent return of Malian security force personnel to protect them. Among those they said they contacted were security force personnel – including gendarme and army personnel – based in Bankass, just 15 kilometers away. They said they continued raising the alarm and appealing for help until shortly before the attack.

A Peuhl elder in Bamako said:

I received updates [from Ogossagou] every five minutes – that armed men were flooding into the area, that they were firing in the air, that they were concentrating as they had before the first massacre. I communicated the situation far and wide. Well into the night, as the villagers realized all our efforts to get the army to return were in vain, it was total panic.

A witness who had attended a meeting of high-level government and MINUSMA officials in Mopti region the day after the massacre said that the Mopti region’s governor, Abdoulaye Cissé, was livid that he had not been informed of plans to remove Malian military forces. At the same meeting, the witness said, a high-level government official said three ministers, including the defense and security ministers, had been contacted in the early evening of February 13 to raise the alarm about the likelihood of an attack.

“I’ve never seen an alert as loud and widely disseminated like this,” the person who attended the meeting said. “It was clear that every possible political and military authority, as well as MINUSMA, was informed of the likelihood of an imminent attack by armed Dogon men on the Peuhl community – ministers, gendarmes, police and army commanders, the UN, the judiciary, religious leaders. With millions of dollars spent on early warning and all the commitments for civilian protection, how could this possibly have happened?”

A government delegation, with over 20 vehicles and senior military officers, visited Ogossagou the day after the attack. Two members of the delegation described having to pass through over 10 unofficial checkpoints between Sévaré and Ogossagou, all of which were manned by Dogon self-defense group members armed with assault weapons. The heavy presence of armed men contradicted promises made by the government to disarm the militias in the aftermath of the 2019 Ogossagou massacre.

Community residents expressed profound anger and disappointment with both national and international authorities for their failure to protect Ogossagou. “After the massacre in 2019, the prime minster, minister of defense, minister of security, and the president promised to disarm the militias, dismantle militia checkpoints, bring the killers to justice, and ensure the survivors from Ogossagou would be safe,” a community elder said. “But less than a year later, voilà, we just buried over 35 more of our people.”

“The authorities promised that the people who attacked us the first time would be put in prison, and yet they’ve killed again.” another elder said. “Many youths had lost their parents in the first incident and now they’re dead, too.”

UN Troops’ Role

Two village leaders told Human Rights Watch that they had called MINUSMA staff and a UN hotline in Mopti shortly after the Malian army left the village on the evening of February 13. They said they were told that peacekeepers were going to be sent to the village. Several people with knowledge of UN operations said there was a group of several dozen Senegalese peacekeepers stationed at a temporary base in Dialassagou, 30 kilometers south of Ogossagou. MINUSMA’s mandate includes ensuring the security and protection of civilians.

Three witnesses said that around 4 a.m. on February 14, about an hour before the attack began, a convoy of at least four UN vehicles passed by Ogossagou – on the road that separates the Peuhl and Dogon neighborhoods – but failed to stop in the Peuhl neighborhood, even though several villagers signaled for help with flashlights.

“I saw four or five white vehicles on the road,” one resident said. “We said, ‘Thank God they have arrived.’ But to our surprise they didn’t stop to talk to us. We didn’t see them again until they showed up with the army around 8 a.m., later that morning.”

“Two of us went out and signaled with our flashlights for several minutes, but [the UN vehicles] rolled past us,” said another. “I saw the brake lights as the convoy rolled to a halt near the edge of the village – in front of the Dogon neighborhood. We thought they’d stopped – but then, some minutes later, they continued. Our hearts sank.”

The same three witnesses said that when MINSUMA came to the village after the massacre, the peacekeepers were asked why they had failed to protect them. One witness said, “I told the UN, ‘We signaled to you, but you didn’t stop! Why?’ The Senegalese commander said that they had not seen the flashlights and had asked a group of Dogon at the edge of town where Ogossagou was, but that the Dogon told them it was further down the road.” The witnesses believed that the Dogon men had deliberately misdirected the peacekeepers.

Response from the Malian Government and MINSUMA

On March 4, Human Rights Watch requested from the Malian government and MINUSMA a response to the events of February 13 and 14, 2020 in Ogossagou.

A letter from the Ministry of Defense and Veterans Affairs, received on March 13, said that, “On the issue of the withdrawal of the FAMA, a tactical error led to a new massacre in Ogossagou,” noting further that, “Disciplinary measures were immediately taken, as a precautionary measure, pending the outcome of the investigations, which have been opened.”

Another letter from the Ministry of Justice and Human Rights, also received on March 13, said that following the massacre, “Investigators from the Specialized Judicial Unit were immediately dispatched to the scene,” and a judicial inquiry was opened to investigate the involvement of “a combat group in connection with a terrorist undertaking, murder, assault and battery, arson, damage to property, and possession and carrying of weapons and munitions of war.” The letter noted that one suspect had been indicted while arrests of other suspects would be forthcoming.

In late February, open sources reported that the government replaced General Keba Sangare, commander of ground forces of the army, and Colonel Amara Doumbia, the Mopti Region Zone commander, without providing details.

On March 16, Human Rights Watch received an email from MINUSMA’s Director, Strategic Communication and Public Information, noting “The protection of civilians and the promotion of human rights is a paramount priority for MINUSMA. MINUSMA has initiated a fact-finding investigation into the events of Ogossagou of 14 February where civilians were killed. The investigation’s findings will be made public very soon.”