Libya began descending into chaos after Muammar Gaddafi was overthrown in 2011. Could you summarize the complex situation in Libya today?

The latest conflict started in April 2019, when an armed group in eastern Libya called the Libyan National Army (LNA), led by commander Khalifa Hiftar – a former general in the Libyan army under Muammer Gaddafi – launched an offensive against Tripoli. Currently, there are two entities calling themselves “the government” in Libya. One, based in Tripoli, is the Government of National Accord (GNA), formed in 2016 by the UN after lengthy political negotiations. The second entity, now in eastern Libya, was voted in during disputed elections in 2014 and refused to disband when the GNA was installed by the UN. This second entity is allied with the LNA, and the House of Representatives elected in 2014.

While we don’t take a position on the legitimacy claims of either government, both groups, and forces supporting them, have a responsibility to protect civilians.

Additionally, parts of the south of Libya, the largest region, are like the Wild West. No one controls it. This is the gateway for human smuggling and trafficking mostly from sub-Saharan Africa to destination countries in Europe and elsewhere. Also, the current chaos allows for proliferation of extremist groups.

What’s life like in and around Tripoli?

When you’re in central Tripoli, you often don’t notice much of the armed conflict. You can sometimes hear the planes and airstrikes, but the shops are open, people are working, many schools are open. But start moving 10-15 km south, to the heavily populated southern suburbs, and you’re confronted with it. It’s a war zone. You see armed groups driving around in pickup trucks with mounted weapons on top. Checkpoints are everywhere, people are afraid. You hear artillery fire and airstrikes, the buzz of armed drones.

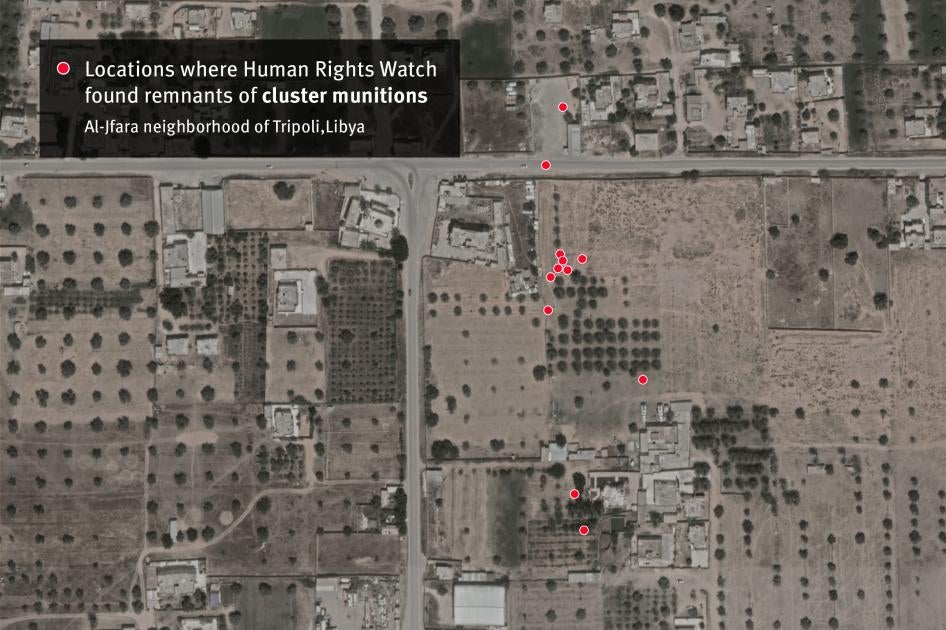

Although the LNA currently has the upper hand in air power, both parties have put civilians at risk by indiscriminately firing into residential areas and using some weapons that are inherently indiscriminate, meaning they can’t be properly aimed, and you don’t know where they’ll land. They’re unlawful to use in populated areas.

What did you see?

We found a reckless disregard for the protection of civilians. We documented airstrikes, drone strikes, and cases where artillery shelling killed people in their homes. In many cases, because of their indiscriminate nature, these strikes are a violation of laws of war, in some cases a war crime. The LNA has used cluster bombs, which are a prohibited weapon. We documented disappearances, allegations of extrajudicial killings of fighters, and desecration of bodies of fighters.

I visited medical clinics that were damaged and shut due to the fighting. I visited a school that had rocket remnants in one of the classrooms after an attack that resulted in its closure. I visited apartment buildings and homes that had been hit. And the most terrible thing you do is speak with people who tell you about their loved ones killed and the neighbors who are dead.

Since the conflict began, violations have been committed by both sides, but the LNA is likely responsible for the larger number of civilians killed, as they have superior air power and, according to the UN, most civilians were killed in air strikes and drone strikes.

Did anyone you spoke with stand out to you?

I spoke to a young woman who survived an air strike that killed six people, including four children, in the Swani area of Tripoli’s southern suburbs. The destruction on her street right after the attack looked apocalyptic. She meticulously described what she saw. Three neighborhood children who were playing in front of her home were killed by a missile, and the way she described it, it was over in two seconds. She recognized one little boy by his T-shirt, and she thought she saw another little boy’s hand moving. She really wanted to make sure someone was preserving this information. No one had asked her for it before. No one from the authorities had come by, the police didn’t come by. This kind of interview, it is always very difficult. And I knew that by telling me exactly what the four dead children looked like, she was reliving the worst experience of her life.

I also went to a school of almost 800 kids in the Swani area, shut down because two rockets struck it. No one was killed as no one was there. But when the headmistress opened the door to the classroom, you could see the whole roof collapsed and all these rocket remnants spread out across the floor and tables and chairs in disarray. I couldn’t get out of my mind the thought that children are supposed to be here. I have a daughter who is almost four years old and she just started school.

The headmistress was tearful, worried about the children’s future. In western Libya, 220 schools are closed because of the fighting, according to the UN. This affects 116,000 kids.

What other countries are supporting each side in the conflict?

The LNA has military and political support from the United Arab Emirates, Egypt, Jordan, and according to the UN, Russia. Because of this support, particularly from the UAE, they have a massive amount of air power. The LNA also has contracts with fighters from Sudan and Chad, the UN says.

On the other side, the GNA has signed a memorandum with Turkey, which is providing them with weapons, armed drones, and ammunition. The GNA has contracted foreign fighters from Sudan and Chad, the UN says. Thousands of Turkey-backed Syrian fighters are supporting the GNA and are fighting on the frontline.

How is the fighting affecting the thousands of migrants and asylum seekers in Libya?

People are still trying to pass through Libya to reach Europe. They are abused by traffickers, and a few thousand are held in detention centers where they also face abuse. We visited GNA detention centers in western Libya in the past and found malnutrition, awful sanitary conditions, beatings. Whether children or adults, they’re often treated like sub-humans. Last summer, an airstrike on a migrant detention center, reportedly by the UAE, killed 50. The GNA-run center was within a compound run by an armed group, putting the migrants at risk. All these centers should be closed.

Also, it is shameful that the EU is trying to seal off Libya so people can’t escape. The EU supports the armed groups acting as the Libyan coastguard, supporting them to intercept boats with migrants and asylum seekers – bound for Europe – who managed to escape the country, forcing them back to the hell of Libyan detention centers.

What now?

It’s high-time the international community focuses on accountability, and they can start by putting together an international and independent commission of inquiry designed to uncover and preserve evidence of abuses and identify those responsible. The next possibility to do that is at the UN Human Rights Council session, currently underway until March 20.

Also, everyone should stop delivering arms to Libya that could be used in abuses and start respecting the arms embargo. Those countries delivering weapons and other banned material to conflict parties, knowing that they are committing violations, could be complicit in human rights abuses and even war crimes.

**This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity