Just how bad is food poverty in the UK?

It’s really shocking that a rich country like the UK, with a large national income and well-developed health and education system, can find itself in a position where 50 times more people need emergency food parcels compared to just a decade ago. That’s a damning statistic and should make people sit up and realize that even in countries where things seem to be fine, they really aren’t. Families that had been just about scraping by are now being sucked under.

What is causing this huge rise in hunger?

One important factor that people kept mentioning to me was significant changes to the UK welfare system over the last decade. There have been cuts to welfare benefits, with a shift away from the government making sure people have enough to live on.

Instead welfare now focuses on encouraging people to return to work, but punishing them if they don’t take up work by withholding benefit payments, leaving some people without enough money to afford to eat properly. We also found that some working people rely on food handouts.

How is it possible to have a job and still not be able to feed yourself?

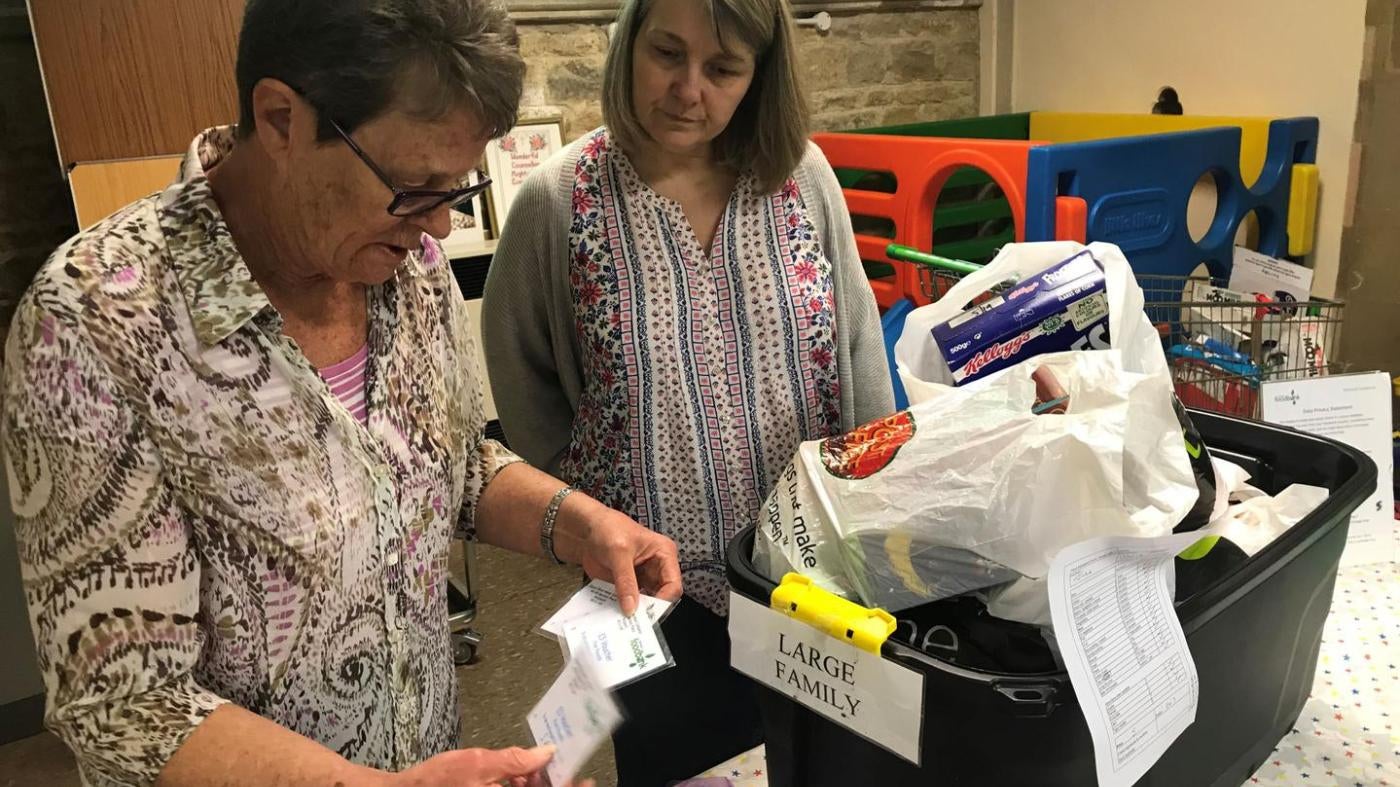

Many people work in very low-paid jobs and also have contracts with irregular hours. But state benefits don’t keep up with this, so you can have peaks and troughs in how much your take-home income is. One mother I met at a food bank – where hungry people are referred to for emergency food parcels – is an ambulance worker. But she is only on call to cover for colleagues if they are ill or on vacation. She is not guaranteed work, and as a result struggles to feed her son. That the very people society entrusts these important jobs to don’t have enough money to feed their children is a terrible situation for the country to be in politically, socially, and morally. I heard so many stories like this.

How does food poverty affect families?

Parents are skipping meals so their children can eat. I met two different groups of women and when I asked them who had gone hungry so their kids could eat, all but one raised their hands. Many people told me that this unseen hunger is growing. One woman said: “You just get used to it, you feel weak, but you just get used to it so your kid has enough to eat.” That can’t be right. I think our report is just starting to scratch the surface of the problem.

Was it hard listening to families’ stories?

Sometimes, yes. Most people I spoke to cried at some point in our interview. It goes to the depth of despair people are feeling. I’m a parent of two primary school-age kids and it really hits home.

It was deeply upsetting to sit with a child whose mother was telling me how she went hungry so her child didn’t have to. We wanted the child to tune out of the interview, so I gave the kid my notebook and some coloring pencils to distract them. Inevitably at some points the mum was in tears, and that was a difficult situation.

People who use food banks are sometimes accused of wanting free handouts. Was that your experience?

The idea that people queue up by the hundreds demanding free food is a myth. Most people coming to food banks and pantries have been referred by an agency, like a school or a doctor or a social worker who’s identified a specific need for that person. There is a huge stigma attached to using food banks. Many people I met were using food banks for the first time and waited until they were desperate. They really do not want to be there.

What surprised you the most?

Probably the phenomenon called “holiday hunger.” Schools provide free lunches for primary school children. But the welfare system doesn’t give extra money to parents for weeks when kids are not in school and able to eat free lunch.

I spoke to parents after Easter break who said that by the end of the holiday they had nothing left in their cupboards. They were scraping together pennies for a loaf of bread and living on cups of tea so their kids could eat.

Parents feel they’re failing their kids. As a parent you want to take care of the family and when you can’t, it hurts. These are basic things: a roof over your head, to be warm, to have enough to eat.

What is the government’s logic in cutting welfare to families?

The stated aim is to cut government spending and restructure the system to get people into work and off welfare. But people struggle to find a job with regular hours and enough pay to feed a family. The UN expert on poverty, Philip Alston, who visited the UK last year, said that the UK’s austerity-based restructuring was mean, punitive, and callous. He hit the nail on the head. Sadly, the fallout of these policies is that people living on the breadline are going hungry.

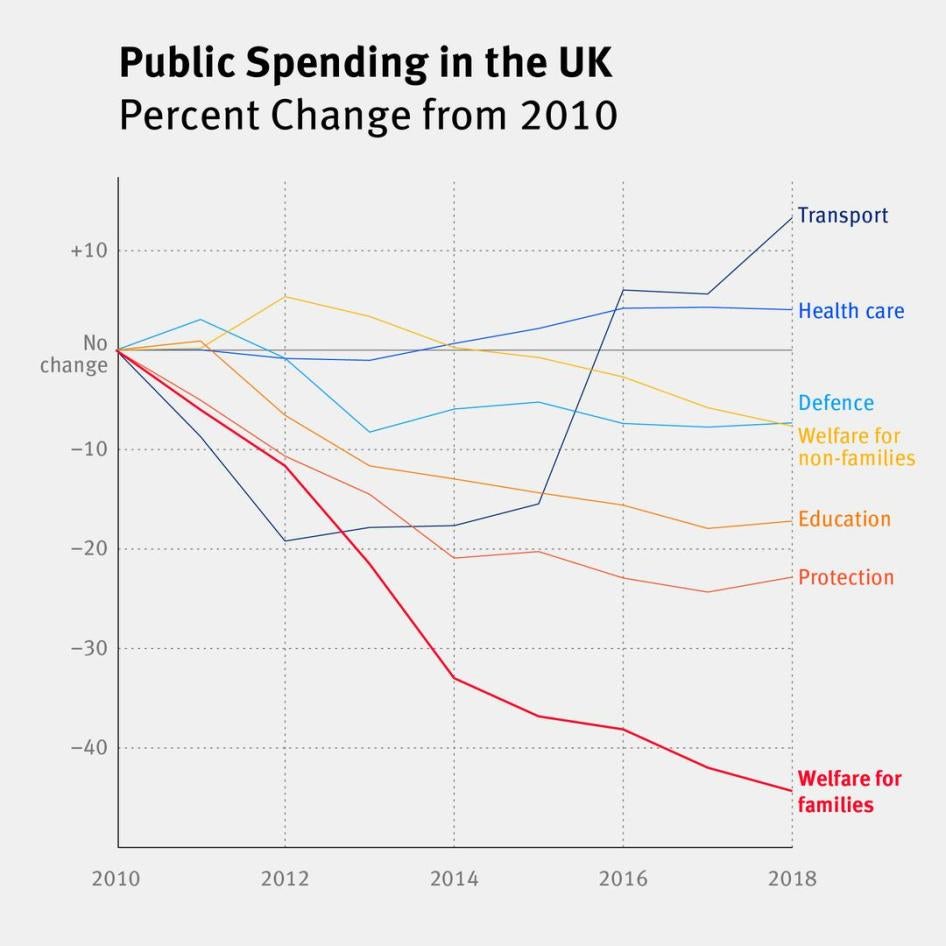

How big were the welfare cuts?

About a decade ago the UK government at the time decided it needed to reduce its overall spending and it made cuts across the board. One decision was to spend less on welfare for families and children - that budget was reduced by around 44 percent. That’s a huge reduction for families who need support.

It’s no coincidence that at the same time as this form of austerity was rolled out, food banks noticed more people coming, and that many of them were families with children. And those people were saying again and again that delays or changes to welfare payments had pushed them under. Anti-poverty groups and food aid providers have repeatedly told successive governments that their welfare cuts are harming people.

So families cannot meet their basic human needs?

Correct, and it helps if we think of these basic human needs as basic human rights that we insist on. Hunger is a human rights issue. People living in the UK have the right to food as part of their right to an adequate standard of living. This was part of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights 70 years ago and is in treaties the UK has signed up to.

Essentially the UK promised that no one in the country would go hungry due to government policy. It’s failing on that promise because welfare cuts are leaving families hungry and dependent on charities for basic food. Moreover, it hasn’t given people who are going hungry due to government policy a remedy, such as being able to sue the government for violating their rights.

The daily grinding reality for many people I met is that state policy is squeezing their incomes to the point where they have nothing left in their cupboards, and they can’t take action against the government to rectify this. That cannot be right.

Do you think food poverty has taken people by surprise?

One charity worker said that if I’d told him a decade ago that today he’d be campaigning to end hunger in the UK, he’d have thought I was joking. So the sheer scale and severity of hunger may have come as a surprise, but frankly the government has been very slow to respond to the many, many indications that it’s getting things wrong. When a state is told to fix its policy because its harming people and it doesn’t, that’s a problem.