What changes for a community once a mine starts operating?

Most mining in South Africa takes place in rural areas, where people live off the land and their livestock. Mining often forces people to leave the land they use for farming and grazing. Mining companies by law are required to make binding commitments for projects that will benefit a community that will be affected by mining. Our experience, however, is that the communities are rarely consulted and, as the South African Human Rights Commission has found in a recent report, compliance with these so-called Social and Labor Plans is poor. In the end, we don’t believe that the plans prioritize the needs of the community and often although local residents were promised employment, it goes instead to people from outside who have the required skills. Few people from the community in practice land a job with the mine.

Also, until recently, the government has allowed mines to operate on lands governed by customary or traditional laws without consulting with or seeking the consent of the communities living on them. In fact, the government has used mining laws to override legal protections for informal land rights. And although people have a right to be compensated for the loss of land even in the absence of formal land titles, we know of several cases in which no compensation was paid.

As a result, we find that the majority of those living near mines are left worse off than before because they no longer have enough land to farm. And to make matters worse, many end up breathing coal dust, getting sick, and their houses, most of which are made of clay, are cracking because of the blasting.

What are people’s biggest concerns?

One of the major concerns is water scarcity. Mines need millions of liters of water to wash coal. I remember one case where, during a drought, the community said the coal mine blocked off the entire stream that was their water source.

Pollution from insufficiently treated effluents - water that runs off after the coal has been washed and that contains toxic substances - and the pollution of streams and boreholes from acid mine drainage are another worry. In places like Witbank in Mpumalanga, where there are many active and abandoned coal mines, people’s tap water is undrinkable. Their only option is to buy water. Yet these are people who cannot even afford the most basic things like sufficient food or primary healthcare.

Exposure to coal dust compromises people’s health. When inhaled, this very fine dust can cause respiratory problems, coughs, and trigger asthma. People end up having to see doctors, which is another expense they cannot afford.

Does the government listen when people voice these concerns?

Local and national government officials rarely respond to formal complaints. A community’s last resort is to take the mine to court. But this takes resources most communities don’t have.

At the end of the day, people are angry. When no one ever responds to their grievances, they resort to protests. It’s only then that the municipalities react – by sending in the police.

Our constitution is very clear. Everyone has the right to peacefully protest without needing to obtain permission to do so. Municipalities, however, insist that unless communities have been granted a formal permission, their protest is illegal. The police are brought in, shoot teargas and rubber bullets into the crowd, and arrest whoever gets in their way. The municipalities will claim the protest was violent and all they were doing was trying to enforce the law. Most protests, however, are peaceful, and most arrests are baseless.

How do the mining companies respond?

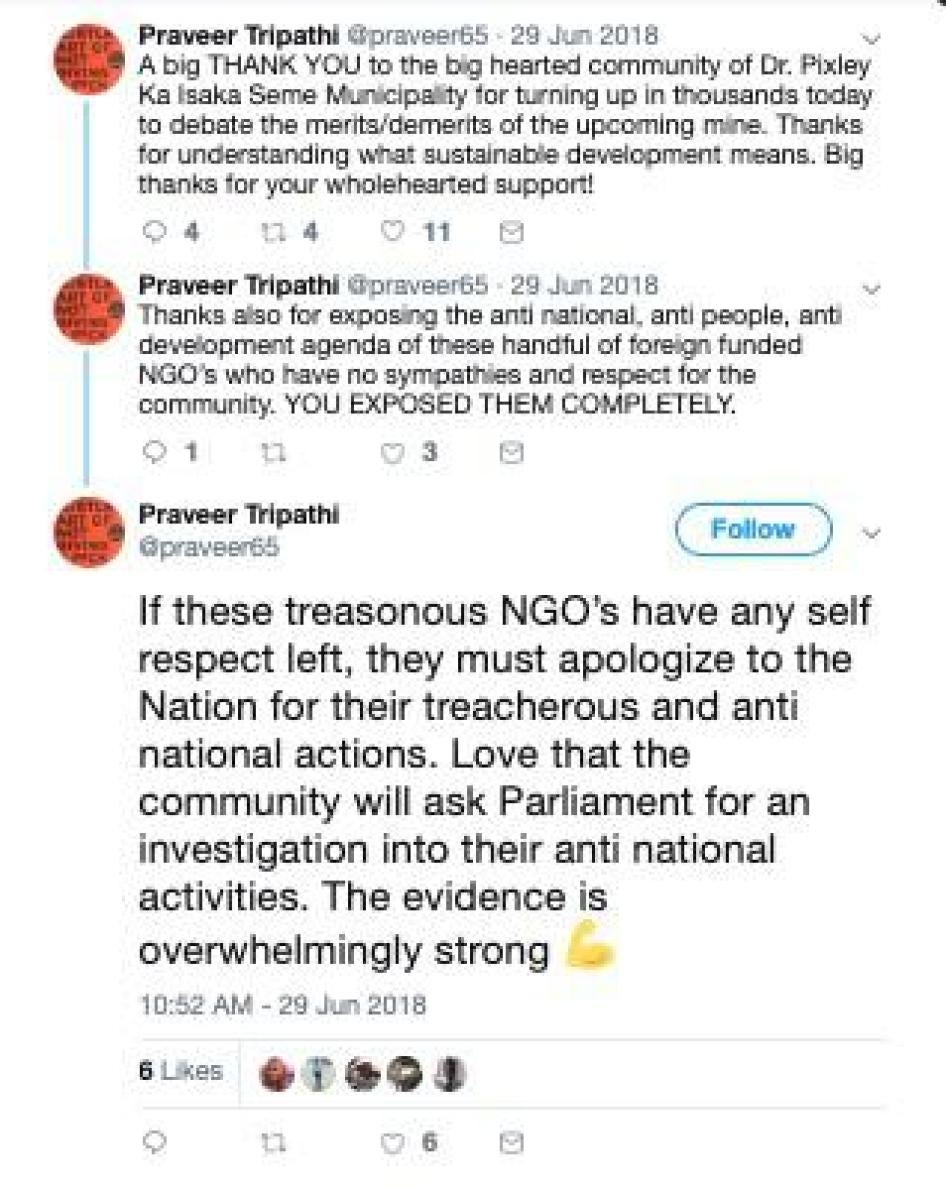

In our work with communities at groundWork we have found that some mines will do anything to discourage people from voicing their concern. They encourage the narrative that anti-mining protests will scare off investors. They want the police to react quickly and decisively. And they put activists at risk by claiming they are destructive and endanger the national interest. In one case, activists told us that they even went so far as to hire small groups of people to gather information about “trouble-makers”.

How dangerous is it to be an activist who challenges mining projects in South Africa?

In KwaZulu-Natal, a province with a violent history and hit-men for hire, the threats activists receive are very real. In Somkhele, an activists’ car was set alight, and at night, he was woken up by gun shots. Somebody tried unsuccessfully to burn his house down. In the morning, he found a dead cat in his yard, he thought it was a warning. Many activists have received anonymous calls threatening that they will be “dealt with”. A female activist and single mother felt so threatened by death calls that she moved herself and her daughter out of the village. Apparently, the village headman was not happy with her opposition to the mine.

What threats have you personally experienced in the course of your work?

A female activist in Mpumalanga had asked us to provide the community with more information about how a proposed coal mine might affect them. The village was in quite a secluded area. Suddenly, a group of armed men burst into the meeting, accusing us of being sell-outs, more concerned about the environment than development. The men did not even come from the community, but in the end, they had whipped up so much anger that 200 to 300 people were chanting the names of our organizations and pointing fingers at us. We felt very threatened and very concerned about the local activist who had invited us. Anything could have happened at that moment. There could have been shooting. So we decided to leave the meeting before the crowd moved outside, gave the lady who had invited us a lift home. and drove off.

Could you do anything to help keep the local activist safe?

We considered relocating her, but she did not want to move. So we bought her a cell phone and checked in on her regularly to make sure she was safe. As a woman she was particularly vulnerable, and we felt she was underestimating the threat. But eventually the situation calmed down.

How do these threats and attacks affect those opposed to mining?

The threats diffuse their courage and passion. There are people, especially the leadership, who say I don’t care, I can die for the truth. But others feel they need to retract. Some have families or dependents they have to look after. They know that anything can happen to them. And there are no security measures in place that make them feel protected.

Do the police not investigate?

Police will break up a protest, but they do nothing when activists who oppose mining are threatened. I don’t know of a single case that has been properly investigated. Not even when people were killed. Take the case of Sikhosiphi “Bazooka” Rhadebe, the chairperson of a community-based organisation in Xolobeni, Eastern Cape. He had raised concerns about a titanium mine that Australian company Mineral Commodities Ltd has proposed. Three years after his murder no one has been arrested.

Some communities have taken the government to court. What was the outcome?

In August last year, the Xolobeni community took the government to court arguing the community should have the right to decide what happens to the land their families have lived on for generations. The court ruled that customary land is only held in trust and that the South African Department of Mineral Resources cannot issue a mining license without the community’s consent. And last November, the Constitutional Court ruled that “restrictions [of protests] that are “blanket in nature” and criminalise gatherings “as an end in itself” are unconstitutional. This means that the protesters can no longer be prosecuted as a criminal offense, whether registered or not. These decisions are significant for the struggle.

What needs to change?

The government should take the injustices committed by corporations seriously. The Minister of Mineral Resources should ensure that issues raised by communities are addressed. The police need to understand that when people are protesting they are not criminals but human beings who care about their communities. And prosecutors should be trained in how to assess the validity of an arrest. We need to resolve these issues in ways that build trust with and calm down these angry communities who feel that, if they don’t fight for their rights, nobody will.

*This interview has been edited and condensed

**groundWork is one of four partners who researched the threats to activists in South Africa’s mining communities, resulting in a joint report “We Know Our Lives Are in Danger” and video. Other partners were Earthjustice, Centre for Environmental Rights and Human Rights Watch.