Summary

I know I am on the hit list.… If I am dying for the truth, then I am dying for a good cause. I am not turning back.

— Nonhle Mbuthuma, community member and spokesperson of the Amadiba Crisis Committee, Cape Town, February 2018

In March 2016, activist Sikhosiphi “Bazooka” Rhadebe was killed at his home after receiving anonymous death threats. Bazooka was the chairperson of the Amadiba Crisis Committee, a community-based organization formed in 2007 to oppose mining activity in Xolobeni, Eastern Cape province. Members of his community had been raising concerns that the titanium mine that Australian company Mineral Commodities Ltd proposed to develop on South Africa’s Wild Coast would displace the community and destroy their environment, traditions, and livelihoods. More than three years later, the police have not identified any suspects in his killing.

Nonhle Mbuthuma, another Xolobeni community leader and spokesperson of the Amadiba Crisis Committee, has also faced harassment and death threats from unidentified individuals. Nonhle recalled talking to Bazooka the day before he was killed. He told her he had seen a hit list that included three people — Nonhle, Bazooka, and another person from the Amadiba Crisis Committee — making rounds in the community. Nonhle fled her home and went into hiding in the days following Bazooka’s death.

Other mining areas in South Africa, including Limpopo, KwaZulu-Natal, and Northwest provinces have had experiences similar to that of Xolobeni. While Bazooka’s murder and the threats against Nonhle have received domestic and international attention, many attacks on activists have gone unreported or unnoticed both within and outside the country.

People living in communities affected by mining activities across South Africa are exercising their human rights to freedom of expression and peaceful assembly to advocate for the government and companies to respect and protect community members’ rights from the potentially serious environmental, social, and health-related harms of mining. In many cases, such activism has been met with harassment, intimidation, or violence.

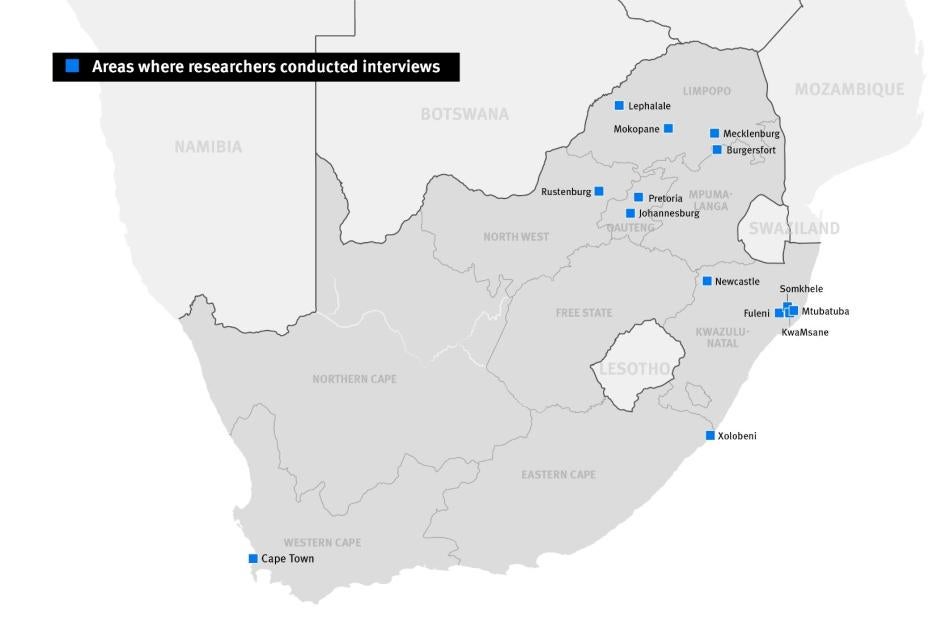

This report documents threats, attacks, and other forms of intimidation against activists in mining-affected communities in KwaZulu-Natal, Limpopo, Northwest, and Eastern Cape provinces, and in domestic nongovernmental organizations challenging mining projects, between 2013 and 2018. Between January and November 2018, two South African nongovernmental organizations working on environmental justice issues, the Centre for Environmental Rights and groundWork, and two international nongovernmental organizations, Human Rights Watch and Earthjustice, conducted over 100 in-person and telephone interviews with activists, community leaders, environmentalists, lawyers representing activists, and police and other government officials.

Killings, Attacks, Threats, and Harassment in Mining-Affected Communities

Some of the activists in mining-affected communities have experienced threats, physical attacks, and/or damage to their property that they believe is a consequence of their activism, while others have received threatening phone calls from unidentified numbers. Women play a leading role in voicing these concerns, making them potential targets for harassment and attacks.

The origin of these attacks or threats are often unknown. So are the perpetrators, but activists believe they may have been facilitated by police, government officials, private security providers, or others apparently acting on behalf of mining companies. Threats and intimidation by other community members against activists often stem from a belief that activists are preventing or undermining an economically-beneficial mining project. In some cases, government officials or representatives of companies deliberately drive and exploit these community divisions, seeking to isolate and stigmatize those opposing the mine.

Community members often do not report the threats or attacks to the police because they fear retaliation from the person making the threat or believe the police would not take their allegations seriously. When police are informed of attacks or threats, they sometimes fail to conduct timely or adequate investigations into the incidents. In many cases, it remains unclear whether the police have even investigated the incidents. Although some of the attacks and threats documented in this report may not be related to community activism against mines, the lack of reporting by community members or failure of police to investigate adequately makes it impossible to determine the cause.

In response to our inquiries, Tendele Coal, a coal company in KwaZulu-Natal, wrote in an email that they “are aware of claims of attacks, yet upon investigation and consultation with Police, the information could not be verified/substantiated.” Two other companies operating in Limpopo, Ivanplats and Anglo American, said that they are not aware of threats or attacks against community members near their mines. In addition, the Minerals Council of South Africa, a 77-member organization that supports and promotes the South African mining industry, wrote in a letter that it “is not aware of any threats or attacks against community rights defenders where [its] members operate.” Ivanplats, Anglo American, and the management of Sefateng Chrome mine in Limpopo welcomed this report’s recommendation on the importance of monitoring threats and abuses against community rights defenders in mining-affected communities.

Extra-Legal Restrictions on Protest in Mining-Affected Communities

When community members seek to protest against mines, local municipalities often create obstacles that have no basis in law. For example, municipal officials have given community members the false impression that all protests need to be “approved,” even though South African law does not have such a requirement and the prevention or prohibition of gatherings is permitted only under very limited and exceptional circumstances.

Municipalities also often unnecessarily require community members to provide documentation of prior engagement with the mining company or to notify the mining company about their plans. In other cases, companies themselves have requested that communities notify companies of their planned protest, wrongfully claiming that this is a requirement under the law.

Several community members interviewed for this report believe that the municipalities are trying to prevent them from protesting. “They want to avoid protests because it could deter investors,” one community member from Lephalale said. Several municipality officials told researchers that they believe their role is to prevent protests.

Extra-legal requirements can effectively mean that community members have to either abandon their protests or face the consequences of protesting without complying with what officials often present as requirements, but in reality, are not.

Police Crackdown on Protest

There is a pattern of police misconduct during peaceful protests in mining-affected communities, including violently stopping protests or unjustified and arbitrary arrests and detentions of protesters.

South African police, using teargas and rubber bullets to disperse protests, have injured peaceful protesters. Police have also arrested community members during protests or other gatherings related to mines, justifying such arrests on grounds of “public violence” or “malicious damage to property,” and have later released the protestors and dropped the charges. In some cases, police have not investigated these incidents or have delayed investigations.

The fear of being jailed, injured, or even killed every time they participate in a protest deters some activists and community members from protesting. “I was not far away from the guy who was shot. Since then, I am afraid to go to marches,” an activist from Limpopo said.

Use of Courts and Social Media Campaigns by Non-State Actors to Harass Activists

South African courts have served as an important venue for some mining companies to silence opposition to mining projects. Some mining companies have tried to intimidate activists through the court system by asking for cost penalties, using court interdicts to prevent protests, and in at least one case, filing strategic litigation against public participation (SLAPP) suits against nongovernmental groups. SLAPP suits seek to censor, intimidate, and silence critics by stifling them with the cost and burden of mounting a legal defence until they abandon their criticism or opposition. Nongovernmental organizations often commit scarce resources to defend themselves in court. One company has also used social media campaigns to harass activists and organizations who are challenging them. SLAPP suits and harassing social media campaigns can take an emotional toll on the activists, and impose a personal, financial, and reputational cost on mining opponents.

Environment of Fear

The threats to personal security of community rights defenders and environmental groups, restrictive interpretation of protest laws, police violence, and harassment through SLAPP suits or social media campaigns have contributed to an environment of fear in some mining-affected communities and environmental NGOs. These tactics have deterred some people from activism against mining; others have toned down or limited their opposition.

South Africa’s Obligation to Protect the Rights of Mining-Affected Communities

International and South African law requires South Africa to guarantee the rights of all people to life, security, freedoms of opinion, expression, association, and peaceful assembly, and the rights to health and a healthy environment. The attacks, threats, and obstacles to peaceful protest described in this report prevent many community activists in South Africa from exercising these rights to oppose or raise concerns about mines, in violation of South Africa’s obligations.

The South African government should urgently take steps to respect and protect the rights of these community rights defenders. The government should direct officials at all levels to comply with the country’s domestic and international obligations to guarantee the rights of people protesting mining across the country, including activists in mining-affected communities.

The Department of Police should ensure that when reports of credible threats against activists exist, law enforcement officials take all necessary steps to ensure the safety of those threatened. Police should also ensure prompt, independent, and thorough investigation of all reports of killings, threats, attacks, or harassment of community members. The Independent Police Investigative Directorate (IPID), which is responsible for investigating claims against the police, should investigate all reports of police intimidating, harassing, and threatening activists. They should also ensure prompt and effective investigation of allegations of police use of arbitrary arrest and excessive force. Municipalities should stop imposing extra-legal requirements on applicants for protests and ensure that the constitutional right to protest is protected. The South African Parliament should revise the Regulations of Gatherings Act in accordance with the 2018 decision of the Constitutional Court on the constitutional right to protest and adopt legislation to protect non-government organizations and activists from SLAPP suits.

Recommendations

To all National Government Agencies, including the Office of the President

- Publicly condemn assaults, threats, harassment, intimidation, and arbitrary arrests of activists, and direct the police and other government officials to stop all arbitrary arrests, harassment, or threats against community rights defenders. Provide adequate and effective individual and collective protection measures to individuals and communities at risk.

- Direct government officials at all levels, in particular in any departments responsible for regulating mining or protests, to comply with South Africa’s domestic and international obligations to respect, protect, and promote all human rights of activists across South Africa, including the community rights defenders in mining-affected communities, to freedom of expression, association, peaceful assembly, and protest, and the rights to health and a healthy environment. Provide all resources necessary for these officials and departments to fulfill their obligations under the South African Constitution and international human rights law.

To the Department of Police, including the National and Provincial Commissioners

- National and provincial police commissioners should ensure that law enforcement authorities impartially, promptly, and thoroughly investigate any allegations or incidents of attacks, threats, and harassment against community rights defenders and the wider community for exercise of their rights to freedom of expression, assembly, and protest, and adopt a plan that would address the failure to adequately investigate such cases.

- Ensure that when there are credible threats against community rights defenders, relevant law enforcement authorities take all necessary steps to ensure the safety of those threatened.

- Investigate any reported cases of police officials, regardless of rank or position, failing to take adequate steps to prevent harm after having been made aware of a reasonably credible threat against a community rights defender. If necessary, adopt a plan that would address the failure to adequately investigate such cases.

- Ensure that law enforcement authorities respect and protect the right to protest, including by not using unlawful measures of crowd control beyond what is strictly necessary to prevent harm to people or excessive harm to property.

- Ensure that community rights defenders and others opposing mines are not arbitrarily arrested or detained, including by complying with of the Constitutional Court’s decision prohibiting the arrest and criminal prosecution of conveners for failing to give notice of a protest to municipalities.

- Ensure that police thoroughly and comprehensively investigate protest-related incidents in mining-affected communities before charging or arresting community rights defenders for any alleged unlawful actions. Ensure that activists charged with criminal offenses are always informed about their rights and provided access to a lawyer.

- Ensure that law enforcement officials or other government authorities who threaten, harass, arbitrarily arrest, or use excessive force against community rights defenders are appropriately disciplined, including, where appropriate, being discharged, suspended, fined, and subjected to criminal sanctions.

To the Independent Police Investigative Directorate (IPID)

- Promptly and thoroughly investigate any reported cases of police officials, regardless of rank or position, being directly or indirectly involved in the killing or assault of any community rights defenders in mining-affected communities and regularly update their families on the progress of the investigation.

To the Directorate for Priority Crimes Investigation (“Hawks”)

- Promptly and thoroughly investigate the killings of any community rights defenders in mining-affected communities and provide regular feedback to their families on the progress of the investigation.

To the Department of Justice

- Ensure access to effective remedies for attacks, threats, and harassment of community rights defenders in mining-affected communities and violations of their rights to life, physical security, and freedoms of opinion, expression, assembly and protest, including through appropriate compensation.

- Train judges on statutory and constitutional requirements that protect non-state litigants asserting constitutional or environmental claims from adverse or punitive cost rulings.

To the National Prosecuting Authority

- Ensure that all prosecutors comply with the Constitutional Court’s decision prohibiting the criminal prosecution of protest conveners for failing to notify municipalities of a planned protest.

To the Departments of Mineral Resources, Environmental Affairs, and Energy

- Direct relevant officials to take steps within their remit to prevent attacks, threats, violence or stigmatization of individuals, groups, and communities who are challenging or raising concerns about mining, and to notify law enforcement officials of any such attacks or violations of their human rights.

- Take steps to prevent interactions between departmental officials and communities, such as meetings or visits to the community, which may result in increased violence against or harassment of mining-affected communities, including by coordinating with the police department on how to mitigate any such risks and consulting with community members.

- Adopt and implement transparent policies and practices that promote financial accountability in mining governance, including public disclosure of all mining applications, authorizations, approvals, permits, licenses, and regular monitoring of impacts required to lawfully conduct operations. Also make publicly available all documentation related to mine permitting decisions, such as minutes of meetings between government and companies, that would be available under an access to information request, with appropriate reasons provided for any decisions taken, to strengthen accountability.

- Ensure that communities receive all relevant information on all adverse environmental and social risks of mining and are free in their decision-making in line with South African jurisprudence. Make such information, including relevant summaries, available in local languages and in various formats, including print, online, and posted on the walls of public buildings, making it accessible to both literate and non-literate community members.

To the Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs

- Ensure that municipalities do not impose extra-legal requirements on applicants for protests in mining-affected communities, and guarantee their rights to freedom of opinion, expression, peaceful assembly, and protest.

- Revise the “guidelines for managing service delivery protests and public marches” for municipalities to facilitate and ensure effective exercise of the right to peaceful assembly and protest.

To the Municipalities and the South African Local Government Association

- Stop imposing extra-legal requirements on applicants for protests and ensure that all community members in the municipality’s jurisdiction can exercise their rights to freedom of expression and peaceful assembly.

- Comply with the Constitutional Court’s decision prohibiting the criminal prosecution of conveners for failing to notify municipalities of a planned protest.

- Ensure that all staff responsible for processing protest applications are trained in the appropriate application of laws and regulations governing protest.

- Investigate impartially, thoroughly, and promptly all allegations that municipal authorities have imposed extra-legal requirements on protest applicants.

- Ensure that all municipal authorities who impose extra-legal requirements on protest applicants are appropriately disciplined.

To the Parliament, including the Portfolio Committee on Mineral Resources, the Portfolio Committee on Energy, the Portfolio Committee on Environmental Affairs, and the Portfolio Committee on Justice

- Revise the Regulations of Gatherings Act in accordance with the 2018 decision of the Constitutional Court on the constitutional right to protest.

- Adopt legislation to protect non-government organizations and activists from SLAPP suits.

To the South African Human Rights Commission

- Investigate allegations of state officials and any companies implicated in intimidation and harassment of community rights defenders.

- Assist community rights defenders and communities affected by mining with information, skills, and resources necessary to respond to security challenges and protect themselves, including through individual and collective protection measures.

- Regularly monitor and report on threats and abuses against community rights defenders in mining-affected communities.

- Call on South African law enforcement and prosecuting authorities to investigate and prosecute those responsible for threats and abuses.

To Mining Companies in South Africa and the Minerals Council South Africa

- Publicly condemn all attacks against community rights defenders in mining-affected communities and nongovernmental organizations opposing mining.

- Develop and implement, in collaboration with mining-affected communities, a grievance mechanism for raising allegations of human rights violations, and take all necessary steps to ensure the safety of anyone who files a grievance. Companies and the Minerals Council should thoroughly investigate and address all alleged incidents reported under the grievance mechanism, and if necessary, take immediate action to remedy human rights violations. The Minerals Council should take disciplinary action against its members that are found to have violated human rights, including by expelling them if necessary.

- Regularly monitor threats and abuses against community rights defenders in mining-affected communities and urge national, provincial, and municipal governments to protect communities and other civil society members who are exercising their domestic and international rights to freedom of opinion, expression, assembly, and association.

- In addition to complying with their existing human rights responsibilities, adopt and implement the Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights, including by recording and reporting allegations of credible human rights abuses by police in their areas of operation to appropriate government authorities and encouraging investigations of allegations.

Methodology

This report documents threats and attacks against community activists, as well as extra-legal restrictions and police crackdowns on protests, in mining-affected communities in KwaZulu-Natal, Limpopo, Northwest, and Eastern Cape provinces between 2013 and 2018. It also documents threats to – and harassment of – South African nongovernmental organizations challenging mining projects.

The United Nations Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders uses the term environmental human rights defenders (EHRDs) to include activists or human rights defenders advocating against environmentally harmful activities, including mining. However, this report uses the terms “community rights defenders” or “activists” to describe these community members. Community rights defenders do not always describe or see themselves as activists or defenders, but instead as advocates for their communities and families.

The findings in this report are based on research conducted in-person and by telephone by two South African nongovernmental organizations working on environmental justice issues, the Centre for Environmental Rights and groundWork, and two international nongovernmental organizations, Human Rights Watch and Earthjustice, between November 2017 and February 2019, including five weeks of field research in South Africa in March, April, August, November, and December 2018. Researchers visited mining-affected communities in KwaZulu-Natal, Limpopo, and Northwest provinces. Researchers also interviewed, in Pretoria, Johannesburg, and Cape Town, NGO representatives that have worked in these communities and in some cases been targets of SLAPP suits or harassing social media campaigns. Researchers conducted additional interviews with activists from Xolobeni in Eastern Cape.

The three provinces on which this research focuses have large-scale and mid-scale industrial mines operating or proposed: The coal mining areas in KwaZulu-Natal (Somkhele/Fuleni and Newcastle), the platinum belt and chrome mining area in Limpopo (Lephalale, Sekhunkune, and Mokopane), and the platinum mining area in Northwest province (Rustenburg). The findings of this report are limited to the areas where we conducted the research.

Researchers interviewed more than 100 people for this report, including 69 people living in mining communities, and more than 20 experts who currently work, or have worked, on mining issues in South Africa, including staff of international organizations, NGOs, health administrators, and academic researchers. In addition to individual interviews, we also conducted four focus-group discussions, each of between eight and 10 participants, in four locations in Northwest (Marikana) and KwaZulu-Natal provinces (Fuleni, Mtubatuba, Newcastle). All participants were informed that they could speak individually to researchers following group discussions. We also interviewed officials of four municipalities, a policeman, three prosecutors, four lawyers, and a ward councilor. Of the 69 community members interviewed, 34 were adult women and 35 adult men. Interviews were conducted in English, or in isiZulu, Xhosa, or Sepedi via an interpreter. All interviewees provided verbal informed consent and were assured that they could end the interview at any time or decline to answer any questions. Where requested or appropriate, this report uses pseudonyms to protect interviewees from possible reprisals. Interviewees were not compensated.

Researchers reviewed secondary sources — including academic research, media reports and relevant South African laws and policies — to verify or corroborate some of the information provided by community members. The background section of this report reviews examples of how mining has caused environmental and social harms in South Africa, and is based on secondary sources, including studies and reports from NGOs. These are harms mining-affected communities face throughout South Africa, including in the areas where we conducted research.

In August 2018, researchers met with government officials at four municipalities in Limpopo (Greater Tubatse, Mokopane, Lephalale) and KwaZulu-Natal provinces (Mtubatuba). In October 2018, researchers wrote follow-up letters to the four municipalities as well as two municipalities (Rustenburg and New Castle) that had not responded to initial meeting requests, the provincial police commissioners in Limpopo, KwaZulu-Natal, Northwest, and Eastern Cape provinces, and the Independent Police Investigative Directorates (IPID) in Limpopo and Northwest provinces. In March 2019, researchers sent the summary of findings and recommendations of this report to relevant government departments, including the Office of the President, Department of Police, Department of Justice, Departments of Mineral Resources, Environmental Affairs, and Energy, and the Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs. At time of writing, no answer had been received.

Researchers also wrote to the companies working in the areas where the research for this report was conducted to request information on the steps taken to address the human rights issues documented in this report. The companies are Tendele Coal (Somkhele Mine, KwaZulu-Natal), Anglo American Platinum (Twickenham Mine, Limpopo), Sefateng Chrome Mine PTY (LTD) (Sefateng Chrome Mine, Limpopo), Ivanhoe Mines (Ivanplats Mine, Limpopo), Tharisa (Tharisa Mine, Northwest), Future Coal PTY (LTD) (Chelmsford Colliery Mine, KwaZulu-Natal), Ibutho Coal Party Ltd (Fuleni, KwaZulu-Natal), Keysha Investments/Transworld Energy and Mineral Resources (Xolobeni, Eastern Cape), and Royal Bafokeng Platinum (Bafokeng Mine, Northwest). We also contacted Eskom in relation to the Medupi coal power plant in Lephalale, Limpopo province. In October 2018, researchers wrote a similar letter to the Minerals Council South Africa, previously the South African Chamber of Mines, to request information. In March 2019, researchers wrote follow-up letters with specific findings and recommendations to the nine mining companies mentioned above, ESKOM, Afarak (Mecklenburg Mine, Limpopo), as well as the Minerals Council about the documented abuses in relation to specific operations.

At time of writing, four out of 12 recipients had responded. In October 2018, the Minerals Council South Africa responded to our general questions in a letter, and Tendele Coal in an email. Researchers also interviewed a representative of Anglo Platinum and received an email from Anglo American which provided general company policies, also in October 2018. In March 2019, Sefateng Chrome responded in a letter to specific questions relating to their operations, while Anglo American and Ivanplats responded in April 2019. All letters received are available on the Human Rights Watch website as an Annex to this report at https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/supporting_resources/sa_reportannex_kr.pdf.

Background

Overall, the mining sector is riddled with challenges related to land, housing, water, the environment.[1]

— South African Human Rights Commission, National Hearing on the Underlying Socio-Economic Challenges of Mining-Affected Communities in South Africa, August 2018

South Africa is the world’s seventh-largest coal producer, and a leading producer of a wide range of metals, including gold and platinum.[2] It holds over 80 percent of the world’s platinum reserves, producing almost 200 tons in 2017, with a total revenue of over 9 billion South African Rand (about US$660 million).[3] Although mining takes place throughout South Africa, most of the country’s platinum mines are concentrated in Limpopo and Northwest provinces, while 60 percent of coal deposits are in Mpumalanga.[4] The Minerals Council of South Africa estimates that, in 2015, mining directly employed 457,698 people in South Africa, representing just over three percent of all those employed nationally.[5]

The Environmental, Health, and Social Costs of Mining in South Africa

The mining sector and the Government of South Africa point out that mining is essential for economic development, but they fail to acknowledge that mining comes at a high environmental and social cost, and often takes place without adequate consultation with, or consent of, local communities.

Labour Issues

As early as the turn of the 20th century, the South African mining industry relied largely on poorly paid black migrant laborers, a practice supported by discriminatory policies and racial segregation under Apartheid that continues today.[6] From that time onwards, mineworkers have worked in dangerous and unhealthy conditions, often far away from their families.[7]

Mineworkers have repeatedly protested their work conditions and low wages, often at great risk.[8] In a tragic recent example that has been referred to as the Marikana massacre, over four days in August 2012, police shot 34 striking workers demanding better wages and working conditions at the Lonmin platinum mine in Marikana, Northwest province.[9] In one particularly horrific incident captured on video on August 16, 2012, police killed 17 workers over eight seconds with a barrage of gunfire.[10] The story made international news and then President Jacob Zuma established a Commission of Inquiry that produced a report that was criticized for its failure to properly address the question of accountability. No police officer has been charged with responsibility for any of the killings.[11]

Environmental and Health Harms from Mining

Because of the absence of effective government oversight, mining activities have harmed the rights of communities across South Africa in various ways. Such activities have depleted water supplies, polluted the air, soil, and water, and destroyed arable land and ecosystems.[12]

As of 2014, many of South Africa’s approximately 6,000 abandoned mines are polluting surrounding surface waters with acidic water and dissolved heavy metals, harming the health and livelihoods of people in surrounding communities.[13] Acid mine drainage from several active and abandoned coal mines, combined with the discharge of inadequately treated effluents from mines, industries, and sewage treatment plants, has made the Olifants River, which flows through South Africa’s Mpumalanga and Limpopo provinces and into Mozambique, one of the most polluted rivers in South Africa.[14] A 2014 study led by the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research to assess health risks related to water from the Lower Olifants River found excess amounts of antimony, arsenic, cadmium, mercury, and uranium in community water supply samples, elements that can be toxic and extremely harmful to human health and marine organisms. Mercury levels were found to be more than 10 times the level the study found to be safe for life-time consumption, based on the daily consumption of just one liter of water from the river a day, and 20 times the safe amount of arsenic.[15] This pollution threatens the entire Olifants River ecosystem, including the lives and health of the many communities in Limpopo Province that depend on this water.[16]

Mining also has grave effects on air quality. Dust generated during the mining process – including from blasting, wind erosion of soil removed to access subsurface minerals, and haul trucks – causes air pollution, primarily in the form of fine particulate matter (PM).[17] For example, a recent government study found that in the Mpumalanga Highveld area, where air quality is extremely poor, mining haul roads contribute 49 percent of the PM10, particulate matter with a diameter of 10 microns or less, found in the surrounding air.[18] Breathing these fine particles can contribute significant harm to human health, including premature death in people with heart or lung disease, aggravated asthma, decreased lung function, and increased respiratory symptoms, like irritation of the airways, coughing, or difficulty breathing.[19]

Mining contributes to high rates of silicosis and tuberculosis in miners. Tuberculosis not only affects miners, but can also be transmitted to family members and others in surrounding communities. Research conducted by the National Institute for Occupational Health in Johannesburg and the University of Cape Town puts the silicosis rate in living miners at between 20 and 30 percent, and it has been estimated that up to 60 percent of miners will eventually develop an occupationally related life-threatening and incurable disease.[20]

Migration of labor to serve the mining sector has also contributed to the HIV epidemic in South Africa.[21] Migrant miners are mostly male, and the prolonged separation from their families and the proximity of sex workers has led to high HIV prevalence. Workers would then transmit the virus upon returning home.[22]

In addition, mining threatens food production because it often takes place on and destroys fertile agricultural land and land used for grazing. A 2012 report by the South African Bureau for Food and Agricultural Production estimated that mining or prospecting licences covered over 77 percent of cultivated land in three districts in Mpumalanga.[23] The South Africa National Policy on Food and Nutrition estimates that between 1994 and 2009, increased mining was largely responsible for a 30 percent decline in the overall land area available for food production.[24] Even after mining ceases and communities regain access to land, the land may not be productive because soils affected by mining cannot be rehabilitated to their original potential.[25] For example, open-pit mining removes much of the nutrient-rich topsoil essential for food cultivation, and acidification can sterilize the remaining soil.[26] Heavy mining machinery compacts the soil so that roots can no longer penetrate deep enough to access sufficient water.[27] Mining can also result in subsidence of soil, which can cause surface water to pool in subsided areas and the higher-lying areas to dry out, frustrating revegetation efforts.[28]

All forms of mining are also energy intensive and produce significant amounts of greenhouse gases (GHGs), including carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide.[29] Combustion of coal for energy production is a particularly large source of GHGs worldwide, causing roughly 25 percent of global annual GHG emissions.[30]

Threats to Existing Land Use

In South Africa, holders of mining rights have the right to preclude other land uses.[31] This often prevents local people from accessing land they depend on for agriculture, housing and other purposes, depriving communities, particularly in rural areas, of their livelihoods. Gauteng High Court, in November 2018, ruled in respect of the Community of Umgungudlovu, which opposes a proposed mine in their community:

The land that comprises the proposed mining areas is an important resource and central to the livelihoods and [subsistence] of the applicants. Many of the applicants utilise the land for grazing for their livestock and for the cultivation of crops and depend on the water supply. The products of their labour are used to sustain their families. Any surplus is sold to generate a cash income.[32]

Because of this connection between their lands and livelihoods, and the pollution resulting from mines, many communities in South Africa are reluctant in consenting to mines on their lands.

Unfortunately, the government has – until shortly before the publication of this report – allowed mines to operate on lands governed by customary or traditional laws without consulting with or seeking the consent of the communities living on them. In fact, the government has used mining laws to override legal protections for land rights. The 1996 Interim Protection of Informal Land Rights Act (IPILRA) requires the majority of a community to provide their consent before disposing of their informal rights to land, which the act defines as “the use of, occupation of, or access to land in terms of any tribal, customary or indigenous law or practice of a tribe.”[33] However, in 2002, the government adopted the Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Act (MPRDA), which conflicts with that provision by allowing the government to grant prospecting and mining permits to land without the consent of landowners.[34]

The government previously accorded the MPRDA precedence over the IPILRA, effectively negating the protections established under the IPILRA. Two recent court decisions, however, have clearly held that communities with land rights under IPILRA must, through a majority of their members, consent to mining operations on lands they occupy or use. In Maledu and Others v. Itereleng Bakgatla Mineral Resources (Pty) Limited and Another, the Constitutional Court overruled an eviction order issued by a lower court to a mining company, permitting it to evict 13 families from a farm in Lesetlheng Community, North West Province, where the company had mining rights.[35] The court held that the Lesetlheng Community, which had informal rights to the land, had not provided consent as required by IPILRA, and thus could not be evicted from their lands through a mining right under the MPRDA. Similarly, in the November 2018 decision Baleni and others v. Minister of Mineral Resources and others, the Gauteng High Court held that communities that have informal land rights under IPILRA “must be placed in a position to consider the proposed depravation and be allowed to make a communal decision in terms of their custom…on whether they consent or not to a proposal to dispose of their right to their land” prior to granting any mining right under the MPRDA.[36]

Role of Traditional Authorities Related to Mining

Despite the protections communities have under IPILRA, many traditional authorities — the customary government structures comprised of a traditional council and a chief, which operate in parallel with the state government — have unlawfully negotiated and “consented” to mines on behalf of communities without consulting them. The South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC) has noted the “belief [of mining companies] that consent for [use of customary land] must be sought from Traditional Councils, and not from the State or from affected communities. Lease agreements are therefore negotiated and concluded with Traditional Councils to the exclusion of other relevant parties.”[37] The Centre for Applied Legal Studies (CALS) similarly noted that:

[S]ome activists explained how they first heard that mining would come to their area from the chief during village meetings which were also attended by representatives of the company. The participants noted that it was apparent from these meetings that the chief was in favour of mining and that the community was not being consulted but rather simply informed of what was to happen.[38]

The lack of consultation between traditional authorities supporting mines and the wider community often leads to the perception in the community that bribery and corruption are taking place and the traditional authorities have been “bought over.”[39]

Traditional authorities also suppress community opposition to mines that they support and “exercise [their] powers to dissuade community members from engaging in actions that are deemed to be at odds with the mining activities in the area.”[40] In 2018, CALS documented various efforts by traditional authorities to stifle opposition to mines in their communities. For example, chiefs have banned activists from attending community meetings, prohibited them from participating if they do attend, and prohibited activists from making use of communal places of assembly.[41] In some cases, traditional authorities label those opposing mines as anti-development and troublemakers, thus alienating and stigmatizing them.[42] As a result, community members are often afraid to speak out against a mine in open consultations.[43] The SAHRC also found that community members sometimes “are afraid to openly oppose the mine for fear of intimidation or unfavourable treatment [by the Traditional Authority].”[44]

Lack of Benefits to Communities

Local communities often do not benefit from mining. Although South African law requires the development of social and labour plans (SLPs) that establish binding commitments by mining companies to benefit communities and mine workers, the Centre for Applied Legal Studies at the University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, has documented significant flaws in the development and implementation of SLPs.[45] For example, a number of procedural inadequacies prevent communities from participating meaningfully in the development of SLPs.[46] And for SLPs to be effective, companies must consult with communities to identify and prioritize the needs in the community. Unfortunately, South Africa’s mining laws and regulations do require public participation in the SLP design process, and communities regularly report that broad-based consultation on developing SLPs does not occur.[47]

The mining laws and regulations also do not require mining companies to make draft SLPs available to the public, so many communities do not see SLPs until they are final, if at all. In one example noted by CALS, the community had to submit a series of letters to the company through their lawyers before obtaining the draft SLP to comment on.[48] The mining laws and regulations also allow mine operators to make decisions about the implementation, monitoring, or amendment of SLPs without consulting affected communities.[49] SLP commitments can thus be weakened without consulting the beneficiaries. The South African Human Rights Commission similarly found that “the current SLP system does not adequately address the negative impacts of mining activities and the shortcomings in the design of, and compliance with, SLP commitments limit their ability to drive socio-economic transformation in mining-affected communities.”[50]

Inadequate Government Oversight and Lack of Industry Transparency

Despite the environmental and social costs of mining highlighted above, the South African government is not adequately enforcing relevant environmental standards and mining regulations throughout South Africa, including in some of the communities where researchers conducted interviews for this report.[51] Although the Department of Mineral Resources (DMR) is responsible for enforcing compliance with environmental and mining laws, the South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC) found that the department often fails to hold mining companies accountable, imposing few or no consequences for unlawful activities and therefore shifting the costs of pollution to local communities.[52] The SAHRC found that “compliance with regulatory obligations, as well as monitoring and enforcement of such responsibilities, remains a crucial concern in the context of mining activities.”[53] For example, the commission found that “the existing sanctions for non-compliance with environmental laws and regulations are inadequate and do not address, nor disincentivise, systemic non-compliance in the sector,”[54] and that the DMR and other governmental agencies often do not respond to complaints filed against mines by community members.[55]

Unfortunately, the lack of government action and oversight has also helped make the mining industry one of the least transparent industries in South Africa.[56] Basic information that communities require to understand the impacts of mines and to hold mining companies accountable for harmful activities is often not publicly available. Such information includes environmental authorizations, environmental management programs, waste management licences, atmospheric emission licences, mining rights, mining work programs, social and labour plans, or compliance and enforcement information.[57] The only way to access such information is through a request under South Africa’s access to information law, a procedure that the World Health Organization has called “seriously flawed” and which the Department of Mineral Resources regularly flouts.[58]

In addition, mining companies and the government rarely consult meaningfully with communities during the mining approval process, resulting in uninformed and poor government and industry decisions that do not reflect community perspectives or have their support.[59]

Activism under Attack: Cases from Mining-Affected Communities

Across South Africa, people living in mining-affected communities are advocating for protection of rights such as the rights to health and a healthy environment, protection from serious social, health, and environmental harms that can stem from mining, which are exacerbated by a lack of transparency, accountability, consultation, and the lack of community benefit from mines.[60] As documented below, some of this activism has been met with threats, attacks, or violence. In addition, municipalities often impose burdens on organizers that have no legal basis, making protests difficult and sometimes impossible.

Researchers also documented cases of police misconduct, arbitrary arrest, and excessive use of force during protests in mining-affected communities, which is part of a larger pattern in South Africa. Mining companies in the country have also been using legal tactics – including strategic litigation against public participation and social media campaigns – to harass activists and organizations who are challenging them. The threats, attacks, and other forms of intimidation against community rights defenders and environmental groups have created an environment of fear that prevents mining opponents from exercising their rights to freedom of opinion, expression, association, and peaceful assembly, and undermines their ability to defend themselves from the threats of mining.

Killings, Attacks, Threats, and Harassment

We know our lives are in danger. This is part of the struggle.

– Billy M., activist from Fuleni, KwaZulu-Natal, March 2018[61]

Activists in several communities told researchers that they or others in their community had been physically attacked or received death threats from known or unknown sources as a consequence of their opposition to mining. In some cases, activist have been killed.

Xolobeni: Attacks Against Community Rights Defenders

Since 2007, members of the Xolobeni community in the Western Cape have pushed back against the government’s efforts to allow mining operations on their traditional land, the area in which their families have lived for generations.

In March 2016, unidentified individuals killed activist Sikhosipi “Bazooka” Radebe, chairperson of a community-based organization opposing mining in Xolobeni called Amadiba Crisis Committee, at his home. His nickname “Bazooka” refers to a South American soccer star.

Members of the Xolobeni community had been publicly raising concerns that a titanium mine proposed by Australian company Mineral Commodities Ltd on South Africa’s Wild Coast would displace community members, and destroy the environment and their livelihoods, which had, until then, depended on farming. The mining company told The Guardian “that the development of the mine and the balancing of the environmental impacts with the social and economic upliftment can be managed to the satisfaction of all stakeholders.”[62] Mineral Commodities Ltd did not respond to a letter from researchers about the research and the mine’s planned operations.

Nonhle Mbuthuma, a leader of the Xolobeni community, told researchers: “We are resisting mining activities in our community because it will lead to the displacement of households, the disruption of our connection to land and ancestors, devastation of our water supply, air quality, marine and estuarine ecosystems, and destroy opportunities for ecotourism and agriculture.”[63]

According to an investigation by The Guardian, villagers believe that Bazooka’s killing was likely linked to his activism.[64] However, the company in a statement to The Guardian refuted claims that it was implicated in the incident as unfounded and pledged to cooperate fully with investigations into his death.[65] The Guardian investigation revealed that mining “has created an atmosphere in which some members of [the] community, eager to profit from future mining, have become violent.”[66] According to Mbuthuma, who succeeded Bazooka as Chairperson of the Amadiba Crisis Committee, the day before he was killed, Bazooka told her he had seen a hit list that included three people — her, Bazooka, and another person from the Amadiba Crisis Committee – making rounds in the community. Mbuthuma fled her home in the days following Bazooka’s death and went into hiding.[67] More than three years later, the police have not identified any suspects in Bazooka’s murder.[68]

In April 2018, Xolobeni community members asked the Pretoria High Court to rule that the South African Department of Mineral Resources cannot issue a mining license without the community’s consent. They also argued that the government should respect the rights of the people who have lived on the land for generations, even if they do not have a formal land title.[69] In November 2018, the court held that the government is obliged to obtain the free and informed consent of the community according to their customs before granting any mining rights.[70] Despite the court decision and continued community opposition, Mineral Commodities Ltd continues its efforts to mine in the area and community activists are still receiving threats and experiencing harassment.[71]

In September 2018, the South African Police Services (SAPS) used tear gas and stun grenades against Xolobeni community members who were participating in a meeting with Gwede Mantashe, the Minister of Mineral Resources.[72] According to Amnesty International, more than 100 members of the Amadiba Crisis Committee had gathered at the tent where the meeting was to be held, holding placards and posters and voicing their opposition to mining in Xolobeni.[73] They had to negotiate with the police before being allowed into the tent.[74] Members of the Amadiba Crisis Committee were limited to a small area at the back of the tent where they were surrounded by police, which made them feel uncomfortable participating in the meeting.[75]

Richard Spoor, an attorney representing the Xolobeni community members opposing the mine, said that after the meeting started, he asked the SAPS deputy provincial police commissioner to create more space for the community members and to remove the police stationed around them.[76] They began to argue after the deputy commissioner dismissed his proposal.[77] When Spoor started to walk away, the deputy commissioner instructed the police to “take him away” and the police pulled Spoor out of the tent.[78] When Spoor tried to re-enter the tent to discuss the incident with the minister and how to resolve it, the police arrested him for assault, disobeying a lawful order of police, and incitement to public violence.[79] When some community members protested, the police used teargas and stun grenades to make them leave.[80] Spoor was released on bail the same day and the National Prosecuting Authority declined to prosecute him on March 15, 2019.[81]

Mbuthuma continues to receive death threats from unidentified individuals.[82] In a media interview in December 2018, she said that although she had thought the threats against her and others opposing the mine would decrease after the court ruling, the situation has not improved. “I am continuously getting calls from people saying that hit men are coming to get me, and as a result I am forced to sleep in different houses every night. I also leave my cell phone turned off for long periods so my whereabouts cannot be tracked,” she said.[83]

Threats and Attacks Against Community Activists in KwaZulu-Natal and Limpopo

Accounts like the ones from Xolobeni are common in South Africa’s mining areas. While Bazooka’s murder and the threats against Mbuthuma have received both domestic and international attention, many threats and attacks on activists go unreported or do not receive public attention.

For example, Billy M., a community activist from Fuleni, a small rural village in KwaZulu-Natal’s King Cetshwayo District Municipality, has received threats from unidentified sources for about five years.[84]

Nestled on the rolling hills of KwaZulu-Natal’s grasslands, Fuleni is located on the doorstep of one of South Africa’s oldest and largest wilderness areas, the Hluhluwe iMfolozi Park. In 2013, Ibutho Coal applied for rights to develop a coal mine in Fuleni that would have required the relocation of hundreds of people from their houses and farmlands, and would have destroyed their graveyards.[85] The mine’s environmental impact assessment estimated that more than 6,000 people living in the Fuleni area would be impacted, and that blasting vibration, dust, and floodlights could harm the community.[86] During the environmental consultation processes, Billy M. led opposition to mining that culminated in a protest by community members in April 2016. The company reportedly abandoned the project in 2016.[87] In 2018 it was reported that a new company, Imvukuzane Resources Ltd, is interested in mining at Fuleni.[88]

Opposition to mining has come at a high cost to Billy M. and other activists. On the night of August 13, 2013, Billy heard gunshots at the gate of his house. He did not know who was responsible for the shots and did not report the incident to the police because he was worried that the traditional leadership might have been involved.[89] More recently, some community members warned him that he will be in trouble if he continues to oppose mining.[90]

Coal mining has long been a reality in Somkhele, as has a feeling of insecurity among those who have voiced their concerns about the impacts of the mine. Some community members believe that coal dust and dust from mining roads may be responsible for strong coughs and other respiratory diseases in the community.[91] They also complain about the noise from the mining trucks and the depletion of water sources.[92]

One of the biggest concerns for community members in Somkhele is the lack of compensation of their customary land they can no longer use due to mining-related activities. One woman in Somkhele said, "There are so many problems we don't even know where to start. We used to have land for farming…but the mine took it away and we did not get any compensation."[93] The mining company, Tendele Coal, has said on several occasions that while it compensates for houses and other belongings, it is legally prevented from paying the community members for the land when they are evicted because the land is owned by the Ingonyama Trust Board (ITB), a traditional body mandated to hold land for communities in that part of KwaZulu-Natal province.[94]

However, South African law gives community members a right to be compensated for loss of their non-formalized right to land, including the use and occupation of – or access to –land.[95] Two recent court decisions confirm that this right to be compensated also exists in the absence of a formal land title, holding that that any decision about customary land requires consent from majority of the community and that people cannot be considered free in their decision to consent unless the question of compensation has been discussed previously.[96] Several community activists opposing the Somkhele coal mine in KwaZulu-Natal, said they have experienced threats, physical attacks, and damage to their property that they believe are in response to their opposition to Tendele coal mine.[97] The night after community members protested against the traditional authority’s alleged involvement with the mine, one of the conveners of the protest noticed some noise outside his house.[98] “When I looked through the window I saw my vehicle was burning,” he said.[99] In 2017, another community member who had expressed his frustration with the mine was cornered and threated by a group of community members on the streets after he attended a meeting to discuss grievances about the mine. “There were about 30 people. I was all by myself,” he recalled. “I felt like I was going to die.”[100] They eventually backed off when someone else distracted them.

In an email response to our enquiries, Tendele Coal, the company operating Somkhele coal mine, said that they “are aware of claims of attacks, yet upon investigation and consultation with Police, the information could not be verified/substantiated.”[101]

Community members opposing Chelmsford coal mine in Newcastle, KwaZulu-Natal have also experienced threats because they oppose mining. Residents of Newcastle’s coal mining areas complain about the environmental harms of mining including dust, damage to their houses from daily blasting, and relocations.[102] A community member who participated in a protest at the mine on August 19, 2016 said, “We heard from the workers at the mine that we should stop or else something bad will happen.”[103] At time of writing, the company had not responded to these allegations.

Shortly after the incident, rumours spread across the village that hitmen had been hired to kill Lucky S., one of the most prominent activists in the area. “A 15-year old boy overheard a group of men saying that I should be killed,” Lucky remembered. “The boy was on his way to herd the goats. He quickly ran home to inform his mother. His mother then called me immediately to warn me.”[104]

Similar concerns have arisen in mining communities of the platinum belt in Limpopo. Elton T. is a community activist and a member of the steering committee of the Mining and Environmental Justice Community Network of South Africa (MEJCON), which has engaged in a government-led process aimed at creating a national mining charter that would establish rules to distribute the country’s mineral wealth more equally among citizens, including by increasing the percentage of black mine ownership and community benefits.[105] Elton expressed concern about the lack of community involvement at national mining charter meetings in late 2017. In December 2017, he started receiving calls from a private number threatening that if he continued his involvement at the mining charter meetings, the caller would “make a plan” to make him stop.[106] He received four calls within a few weeks warning him to withdraw from the process. Despite the threats, Elton continued his activism.[107]

In addition to our research, several other NGOs have recently documented threats facing human rights defenders and activists in South Africa, including in mining-affected communities. For example, the Centre for Applied Legal Studies has investigated various forms of victimization faced by activists, mainly in mining communities, including death, violence, frivolous litigation, and criminalization of their activities.[108] The Heinrich Böll Foundation, with assistance from the Legal Resource Centre, has detailed incidents of killings and other physical violence against activists in mining-affected communities of South Africa.[109]

In its November 2018 review of South Africa’s compliance with the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) expressed concern about “reports of human rights defenders, particularly those working to promote and defend the rights under the Covenant in the mining and environmental sectors, being threatened and harassed.”[110] It recommended that South Africa provide a safe and favorable environment for the work of human rights defenders to promote and protect economic, social, and cultural rights, including by…[e]nsuring that all reported cases of intimidation, harassment, and violence against human rights defenders are promptly and thoroughly investigated and the perpetrators are brought to justice.[111]

The Minerals Council South Africa, a 77-member organization that supports and promotes the South African mining industry and whose members include companies operating mines in some of the communities represented in this report, responded to researchers of this report that it “is not aware of any threats or attacks against community rights defenders where our members operate.”[112]

Impacts on Women Activists

Women are often first to experience the harms of mining and can play a leading role in voicing these concerns, which makes them potential targets for harassment and attacks.[113]

Lebogang N., an activist from Fuleni, has received several death threats from fellow community members who were hoping that a coal mine could bring them jobs.[114] In April 2017, Lebogang’s cousin told her that others in the community wanted her to stop opposing mining, and that “the only way to stop [her] is by killing [her].”[115] A few days later, another cousin told her that people in the community were trying to kill her.[116] The village headman, who is part of the traditional leadership, told her that she would be banned from the village if she kept opposing mining.[117] Lebogang has not reported these incidents to the police.[118]

Silindile N., a 39-year-old woman from Fuleni, received about five phone calls a day for several days in April 2016, after she had started to mobilize against the coal mine in the community by distributing information about the risks of coal mining.[119] An anonymous caller told her, “You must stop what you are doing. If you don’t stop, we will shoot you.”[120] Silindile said the calls stopped when the mining company pulled out from the project.[121]

Women like Lebogang and Silindile, who are often the main caregivers in the family, also worry about the impacts on their families of threats made against them for their activism.[122] For example, Lebogang turned down an NGO’s offer of support to leave the community. “If I had left I would have worried about my family, especially my daughter,” she said.[123] Research by the Centre for Applied Legal Studies found that threats against women in South Africa adversely affect their children and families because of the role women predominantly play as primary caregivers.[124] Women are also often first to experience the harms of extractive industries on land, water, food, health, and livelihoods. This often motivates them to play a leading role in voicing these concerns and acting as human rights defenders, which makes them potential targets for harassment and attacks.[125]

Creation and Exploitation of Divisions within Communities

In some cases, government officials or companies deliberately create or exploit community divisions or close their eyes to acts of intimidation and abuse between community members, in order to isolate or weaken critics. The South African Commission for Human Rights has found that many mining-affected communities across South Africa are experiencing “the creation of tension and division within communities as a result of mining operations.”[126] Sometimes, threats and intimidation against activists come from community members who have been promised economic benefit from the proposed project or are politically allied with the government or traditional authority. “There is division everywhere,” an activist from Somkhele said. “I believe there were people who were paid to block us from organizing.”[127]

In Somkhele, one community member said, “The mine [operated by Tendele Coal Mining], is not directly threatening people, but they will [intimidate] their employees by telling them that they will lose their jobs if the activism continues.”[128]

Tendele has sought to brand community members opposing its operations as anti-development or as acting against the interest of the community, putting them at further risk of being attacked or threatened. For example, on February 21, 2018, the company’s management circulated a memorandum to employees warning that because “the realities of running out of coal have already started affecting the Mine,” the “January bonus may very well be the last time that employees will received a production bonus” and that management may soon approach the unions to discuss lay-offs.[129] The company blamed these potential cuts on “a few community members [who] … choose to stand in the way of future development and huge economic and social investment and upliftment in the community.” In a letter sent to researchers, the company also asserted some activists “would rather have a devastated economy and no jobs than a responsibly run mine.”[130]

Extra-Legal Restrictions on Protest in Mining-Affected Communities

When the community members apply for a protest [about mining], we call a so-called rapid-response meeting. The goal is to prevent the march from happening.

– Municipal official from Limpopo, August 8, 2018[131]

South African municipalities, the local level of government, often seriously limit the rights to protest, freedom of expression, and peaceful assembly of members of mining-affected communities. Research in KwaZulu-Natal, Limpopo, and Northwest provinces found that local municipalities seek to limit or prohibit protest against mines by imposing requirements that have no legal basis.[132] When municipalities reject or delay approving protest applications, communities often protest without approval, which often leads to police violence and arrests of activists.

Governance StructureSouth Africa is a constitutional democracy with national, provincial and local levels of government that “are distinctive, interdependent, and interrelated,” and an independent judiciary.[133] The local level of government consists of municipalities, which fall under one of three categories: metropolitan, district, or local.[134] In addition, the South African Constitution recognizes “[t]he institution, status, and role of traditional leadership, according to customary law.”[135] |

According to article 17 of the South Africa Constitution, “Everyone has the right, peacefully and unarmed, to assemble, to demonstrate, to picket and to present petitions.” However, community members interviewed for this report struggled with tedious and lengthy protest notification processes created by municipalities that exceed the requirements of South Africa’s Regulation of Gatherings Act (RGA) of 1993, the main legislation regulating the constitutional right to protest.

Notification Process as “Permission-Seeking Exercise”

The RGA requires communities to notify the municipality seven days ahead of a planned protest, unless notification is “not reasonably possible.”[136] Section 5 of the RGA only allows a municipality to prevent or prohibit a proposed gathering if “there is a threat that [the] gathering will result in serious disruption of vehicular or pedestrian traffic, injury to participants in the gathering or other persons, or extensive damage to property, and that the Police and the traffic officers in question will not be able to contain this threat.” If a municipality does not prohibit a protest or otherwise respond to a notice to protest, the protest can proceed legally; the RGA does not require affirmative approval.[137]

Despite these guarantees, however, the South African Commission on Human Rights found that “rather than facilitating the right to freely assemble, many local municipalities apply the provisions of the RGA in a manner that restricts its intended implementation.”[138] “[T]he notification process [under the RGA] has been interpreted by government authorities as a permission-seeking exercise.”[139] In research on the right to protest, Professor Jane Duncan of the University of Johannesburg found that this misapprehension “set the tone for how notifications were dealt with, both by the municipalities and by the police.”[140] For example, two municipal government officials interviewed for this report explicitly referenced the need to “approve” or “disapprove” protests, and explained that many protests were “illegal” because they had not been “approved.”[141]

As a result of misunderstanding or intentionally misinterpreting the protest regulations, municipalities are illegally or inappropriately denying permits, as reported by the Right to Protest Project.[142] The UN CESCR also expressed concern “at the high number of rejections of protest applications [in South Africa] owing to deliberate restrictions or inadequate understanding of legislation by public officials.”[143] The CESCR recommended that South Africa review “the Regulation of Gatherings Act No. 205 (1993) with a view to preventing it from being abused to suppress peaceful protests and ensuring that the Act and its related regulations are adequately enforced by public officials.”[144]

Misinterpretation of Section 4 Meeting Requirements

Another obstacle to the ability to exercise the right to protest relates to irregularities around convening of special meetings authorised under Section 4 of the Gatherings Act when local municipal officers believe that the notice to protest warrants further discussion with the applicant.[145] Under that provision, if the municipal officer, after consultation with the police, determines that a meeting is “necessary,” the officer must, within 24 hours of the protest notification, call a meeting with the convener of the protest, local municipal officials, and police authorities “to discuss any amendment of the contents of the notice and … conditions regarding the conduct of the gathering.”[146] If a convener has not been called to a meeting within 24 hours after giving notice to protest, the RGA provides that the protest “may take place.”[147]

However, some municipalities incorrectly tell convenors that the protest cannot go ahead without a Section 4 meeting regardless of whether the municipality has called one within 24 hours of receiving notice or has failed to ensure that all the required officials attend the meeting. This happened in Lephalale, an area in the northwest of Limpopo province, where coal mines and Eskom coal-fired power plants contribute to air pollution that threatens the health of local communities.[148] Eskom estimates that emissions from 13 of its 15 coal-fired power stations cause 333 premature deaths per year.[149]

In Lephalale, a community near the Medupi power station, the municipality was notified of several marches in 2016 and 2017. According to the community members interviewed, the municipality did not request a Section 4 meeting within the 24-hour period, yet insisted that protests cannot go ahead without “approval.”[150]

Lawyers for the Right2Protest Campaign, a nongovernmental organization, also documented several cases across South Africa, including in the provinces covered by this report, where the municipality delayed the decision about the protest because the police did not attend the scheduled Section 4 meeting.[151]

In some instances, companies have also argued that a protest could not go ahead because of the absence of police officials at the Section 4 meeting. Such a situation arose at Tharisa mine in Marikana, operated by Tharisa Group. The area around Rustenburg in Northwest province is one of the areas with the highest density of mines, and experiences many of the mine-related environmental and social challenges that come with such intense activity.[152] At Tharisa mine community members are concerned that the large influx of male workers from across the country is threatening health care because health services to meet the needs of the increased population and workers are not sufficient. For example, one woman said, “We have high HIV rates here, but people don’t have access to treatment. It’s amazing because we are surrounded by big wealthy mines.”[153] People living in informal settlements in the area are particularly concerned about the significant harms caused by the pervasive dust and noise from the mines.[154] At time of writing, the company had not responded to these allegations.

The Marikana Youth Development Organization and the Right2Know Campaign applied for a protest to occur on August 16, 2018 – the sixth anniversary of the Marikana massacre. On the eve of the planned march, Tharisa mine management wrote the applicants, telling them to cancel the protest because the South African Police Service was not present at the Section 4 meeting.[155] When challenged in court, the judge decided that the march could go ahead.[156]

The Right2Know Campaign’s Murray Hunter, who has assisted communities across the country with protest applications, said, “The Section 4 meetings are only supposed to happen when there is a specific security risk. But we have seen how it has been abused by municipalities [to keep people from protesting].”[157]

Extra-Legal Requirement of Notifying or Receiving Consent of the Mine or Traditional Authorities

Nothing in the Regulation of Gatherings Act requires protestors to attempt to engage with the mining company to resolve their grievances before a protest, or to notify the company about the planned protest. Nevertheless, municipalities have required conveners to provide documentation of such efforts before protesting. For example, municipal officers interviewed in Limpopo and KwaZulu-Natal stated that communities must directly engage with the mining company before applying for a march related to a particular grievance.[158] One officer argued that notification was a legal requirement, claiming that “[t]he [Gatherings] Act says that it is the responsibility of the convener to notify the mine.”[159] While it may be a reasonable expectation of companies to be notified about any planned protest near their operations by the police or municipality, this is not a legal obligation for the conveners. Some municipal officials acknowledged that notification to the company is an extra-legal requirement imposed by the municipality. One official from Limpopo said: “The requirement to contact the mine is coming from the municipality. We do it so we are not getting blamed by the mine.”[160]

Mining companies have also requested that communities notify or even engage with them ahead of their planned protest, wrongfully claiming that this was a requirement under the law.[161] For example, Tendele Coal company representatives in Somkhele said that the conveners need to engage with them on their grievances prior to applying for a protest at the municipality.[162]

Municipalities have sometimes disapproved protests if the mining company has indicated an intention to address the protesters’ grievances. For example, one official from a municipality in Limpopo’s platinum belt said, “We disapprove the march if the issue has been addressed. For example, if the mine commits to addressing the grievance.”[163] However, nothing in the RGA supports such a practice, and the right to protest is not conditioned on a government official’s determination whether the protester’s concern is being addressed; the right exists independent of the content of the protest.

Some municipalities, such as Mokopane and Greater Tubatsein Limpopo province, also require protest applicants to show the written consent of the mining company to receive a so-called memorandum, a document listing the demands of the community members which is typically handed over to mining companies, as a condition for approving a march.[164] Again, nothing in the RGA supports such a requirement. Even if the rationale for seeking such an assurance may be to prevent frustration for the protesters, researchers have identified it as a “censorship device, where those who are being marched against can squash the protest simply by refusing to accept the memorandum.”[165]

In some areas of North West province where traditional leadership structures are particularly powerful, municipalities have also required the consent of the traditional leader as a precondition for a protest, although there is no basis in law for such a demand. For example, in 2015, when the Bafokeng Land Buyers Association, a local human rights organization based in Rustenburg, applied for a protest on behalf of community members near Bafokeng mine, the municipality told them that they needed a letter from the chief authorizing the protest.[166] Such a requirement is particularly problematic because, as explained by Eric Mokuoa, a campaigner who works with many mining-affected communities across South Africa, “traditional leadership plays a strong role regarding the suppression of protest” by influencing municipalities in their decisions about protest applications.[167]

Misinterpretation of Department of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs’ Guidance