Anglophone regions have killed scores of civilians, used indiscriminate force, and torched hundreds of homes over the past six months, Human Rights Watch said today. Armed separatists have assaulted and kidnapped dozens of people during the same period, executing at least two men, amid intensifying violence and growing calls for secession of the North-West and South-West regions.

Violence has intensified since October 2018 as government forces have conducted large-scale security operations and separatists have carried out attacks. Cameroon’s government should investigate allegations of human rights violations and ensure that civilians are protected during security operations. Separatist leaders should immediately direct their fighters and followers to halt all human rights abuses and to stop interfering with children’s education.

“Cameroon’s authorities have an obligation to respond lawfully and to protect people’s rights during periods of violence,” said

, Central Africa director at Human Rights Watch. “The government’s heavy-handed response targeting civilians is counterproductive and risks igniting more violence.”

Since October, at least 170 civilians have been killed in over 220 incidents in the North-West and South-West regions, according to media reports and Human Rights Watch research. Given the ongoing clashes and the difficulty of collecting information from remote areas, the number of civilian deaths is most likely higher.

Human Rights Watch interviewed 140 victims, family members, and witnesses between December and March, including 80 in person in the North-West and South-West regions in January.

In the fall of 2017, Cameroonian security forces suppressed large-scale protests organized to celebrate the symbolic independence of Anglophone regions from the country's French-speaking areas, killing more than 20 protesters. Since then, the emergence of armed separatist groups has been accompanied by attacks and a growing militarization of the Anglophone regions. The unrest has displaced more than a half-million people since late 2016.

Human Rights Watch research shows that since October, security forces, including soldiers, members of the Rapid Intervention Battalion (BIR), and gendarmes, killed civilians, used force indiscriminately, and destroyed and looted private and public property.

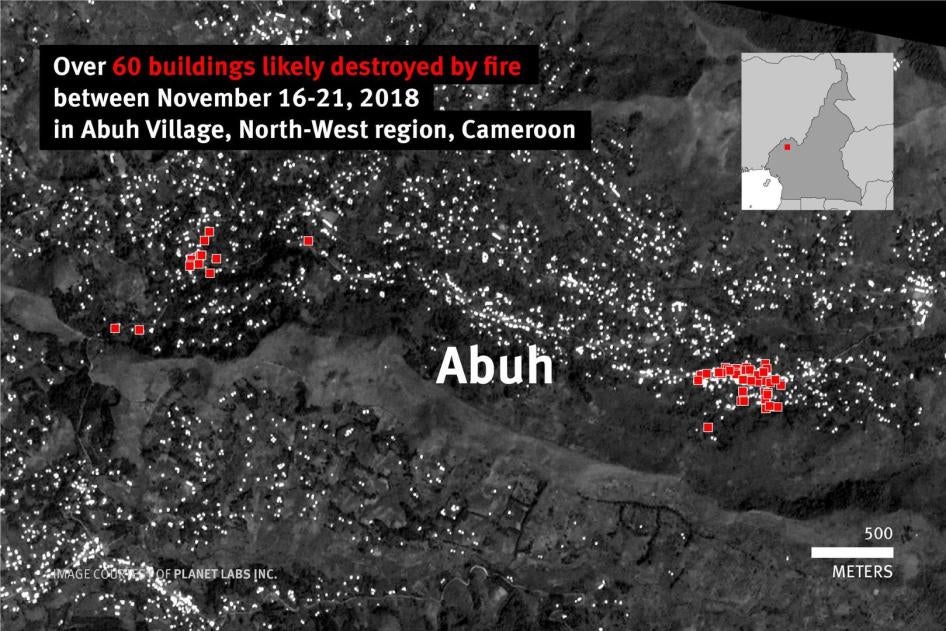

In one case, witnesses said, Cameroonian security forces attacked the village of Abuh, North-West region, in November and burned an entire neighborhood to the ground. Satellite images and photographic evidence obtained by Human Rights Watch show the destruction of up to 60 structures.

A woman in her 40s said she spent three days hiding in the surrounding countryside with her five children after the attack: “When I came back to the village, my house was gone, with everything inside. I am left with nothing but my clothes.”

The government’s near-total lack of prosecutions for crimes by security forces in the Anglophone regions has protected those responsible and fueled abuses.

At least 31 members of the security forces were killed in operations between October and February, in both the North-West and South-West regions, according to credible media reports and information collected by Human Rights Watch.

Witnesses said that separatists assaulted government workers, teachers, and students, preventing them from going to work or to school.

Kidnappings by separatists have also surged, including more than 300 students under age 18 kidnapped in at least 12 incidents. All were released, most after a ransom was paid.

In one case, a man in his 50s said separatists kidnapped and held him for ransom days after the October presidential election – an exercise the separatists opposed – as he drove between Kumba and Buea in the South-West region. He was taken to a remote base operated by the Ambazonia Restoration Forces – one of the armed separatist groups operating in the Anglophone regions and affiliated with the Ambazonia Interim Government – where he said he saw fighters execute two young men. “They were accused of voting,” he said. “They were beaten to death.”

Cameroon’s partners, France in particular, should increase pressure on the government to hold those responsible for abuse to account, and ensure that any support to Cameroonian security forces does not contribute to or facilitate human rights violations. The UN Human Rights Council should ask the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) or relevant UN experts to conduct a fact-finding mission into allegations of human rights abuses in Cameroon. Members of the UN Security Council should formally add Cameroon to the Council’s agenda, request a briefing on the situation from the UN Secretary General, and make clear that individuals responsible for serious human rights violations could face sanctions.

“It is absolutely essential for the Cameroon government to restore the rule of law in the Anglophone regions and to hold those who target civilians to account,” Mudge said. “Leaders of the separatist groups should stop abusing civilians and show they are willing to resolve this crisis.”

On February 12, Human Rights Watch sent a letter with its findings to Ferdinand Ngoh Ngoh, secretary general at the presidency requesting a response to specific questions. The government’s March 22 response denies state security forces carried out abuse documented in this report. The government added that its security forces all undergo human rights training prior to deployment and that about 30 cases are pending before the Military Courts in Bamenda and Buea for crimes including torture, destruction of property, violation of orders, and theft.

To protect witnesses and family members, Human Rights Watch has withheld the identities of some victims and interviewees.

Four Rom residents told Human Rights Watch that soldiers and gendarmes attacked their village and the neighboring Nsah locality on the evening of October 21, forcing residents to flee into the bush. Security forces killed at least four civilians, including a young man with a physical disability who used a wheelchair. A resident of Nsah said:

Security forces also burned up to 20 buildings in both Rom and Nsah, including family houses, stores, and a Baptist Church. Community members said that, fearing more attacks, an estimated one third of the town’s population are living in the bush or nearby localities.

Abuh, Muteff, and Ngwah (North-West region), November 19-21

Five witnesses said that soldiers, Rapid Intervention Battallion (BIR) members, and gendarmes began a three-day security operation in the villages of Abuh, Muteff, and Ngwah on November 19. Armed separatists had operated in the area since at least July. Witnesses said that soldiers burned up to 60 homes in Abuh. They said they believed that the security forces retaliated against civilians suspected of harboring separatists. Human Rights Watch has confirmed the burning through satellite imagery. Security forces also set ablaze three homes in Muteff and partially destroyed the Abuh City Hall, looting and burning solar panels donated by a charity.

A 51-year-old man, who ran to the neighboring hills when security forces approached Abuh, recalled what he saw from his hiding place: “The burning lasted for three days. We saw how the military destroyed our homes.” The man’s compound was burned on the second day, which is when he said most of the destruction occurred: “I had a big house. Everything is gone. I didn’t assess the damage yet. Every time I try do it, it makes me ill.”

All five witnesses confirmed that there was no confrontation between the security forces and the separatists. Another resident of Abuh said that the separatists, who had based themselves in the targeted neighborhood, fled when security forces arrived: “There was no clash during the three days. There was just burning by the military of our houses. It was like a revenge.”

Before entering Abuh, the security forces stopped in the village of Ngwah, killed two elderly men in their homes, and shot an elderly woman, who later died in a hospital, two residents said.

In its March 22 letter to Human Rights Watch, the government of Cameroon wrote that operations conducted by the national army in Abuh, Muteff, and Ngwah between November 19 and 21 had two objectives: to protect ethnic-Fulani suffering separatist abuses and to secure the area by “neutralizing the perpetrators of these abuses against the civilian population” if necessary.

Bali (North-West region), November 22

Residents of Boh-Nanden, a neighborhood in Bali village, said they fled into the bush as they heard an attack on the nearby camp of the Ambazonia Restoration Forces. Seven witnesses and five others said that a civilian’s body was booby-trapped with explosives after the attack. They believed it was the body of a 21-year-old man who returned home soon after the shootings subsided. People who returned later found his body in the street. As they lifted the body, an explosive device apparently connected to him went off, killing 2 more civilians and injuring at least 11, said witnesses and five people injured in the incident.

One of the survivors, whose leg was amputated, said the booby-trapped victim was a neighbor’s son:

He had been shot in the head. I volunteered with [five] men to lift his body and carry it to be taken for burial. As we picked up the body, we heard a loud explosion. I didn’t understand anything. I was covered in blood and my left leg was hurting. I had to wait until 5 p.m. before being taken to hospital. No one wanted to move when soldiers were around.

Accounts from three other victims and witnesses, supported by photos and videos Human Rights Watch collected, indicate that gendarmes later burned at least 13 houses in various areas of Bali, including Boh-Nanden, Press Craft Street, and Tih. A businessman said that the gendarmes targeted his home because he had a shop in the vicinity of the separatist camp in Boh-Nanden and was accused of serving the separatists drinks: “I saw the gendarmes coming with three armored cars. They first started firing against my house and then eight [gendarmes] came down, poured fuel and burned everything.”

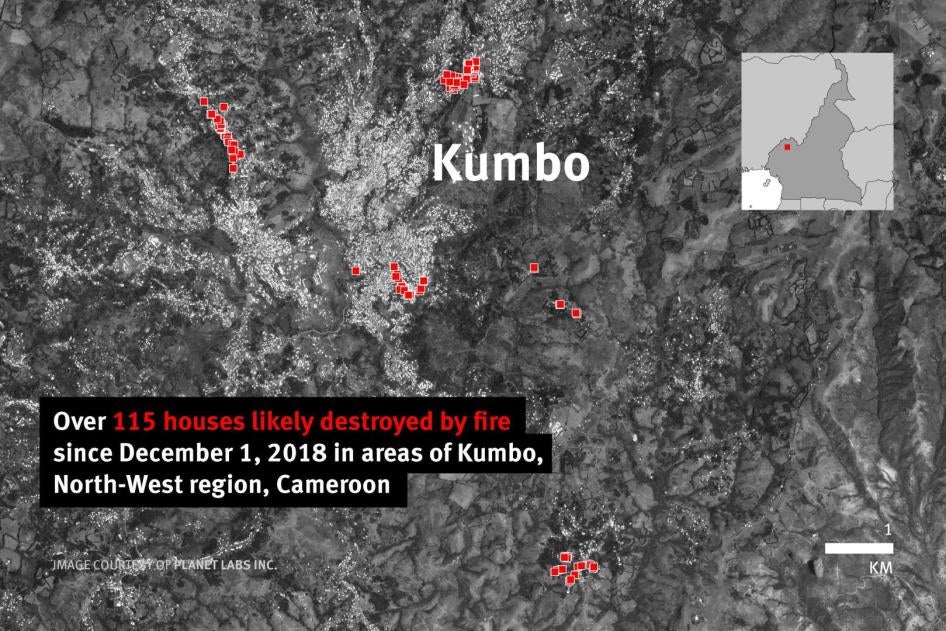

Kumbo, Meluf, Kikaikom, and Nyaro (North-West region)

Since mid-2018, the Bui division has been wracked by violence with its main city, Kumbo, almost completely cut off. Residents said repeated clashes between the separatists and security forces in the area have severely restricted movement.

Witnesses said that in late July, soldiers, BIR, and gendarmes stormed Kumbo’s Njavnyuy neighborhood in search of separatists. They broke into homes, destroyed or looted property, arrested at least five men, and a 14-year-old boy, and beat them outside their homes.

The troops later took the men and the boy to the Gendarmerie headquarters in Kumbo, where the detainees said they found gendarmes beating at least 25 other detainees. “They kept beating us with everything they had,” one said. “I saw three men who had been shot in the legs and were losing a lot of blood.”

One of the five men died there, allegedly from the beatings. Another detainee said: “[The victim] was in bad shape, was lying helpless. When the military were beating us in front of our house, he was hit in the neck with a big wooden stick that the BIR found outside. I think that’s what killed him.”

Three survivors said that gendarmes then drove the man’s body away along with another man, still alive, who was among the six people arrested in Njavnyuy. The following day, both men’s bodies were found dumped in a street in Jakiri village. The other men and the boy were released.

Since the October presidential election, clashes between armed separatists and security forces have increased, leading to more abuses by both sides. For example, soldiers went on a rampage in Kumbo and neighboring localities between December 3 and 6, following clashes with armed separatists, burning dozens of homes and killing civilians. Photographs, videos, and satellite analysis indicate soldiers burned over 55 houses in areas of Kumbo known as SAC Junction and Romajay, as well as in Meluf, Kikaikom, and Nyaro.

A teacher from SAC Junction said that soldiers torched his house, and more than 20 others and a vocational training center nearby after clashes with armed separatists on December 3. When the shooting began, around 5:30 a.m., he hid inside his house, watching soldiers set fire to his neighbor’s home. Around 10 a.m., soldiers turned to his house:

I was on the floor. I peeped out through a hole and saw eight soldiers standing in front of my house. One shouted in French “On brûle!”[Let’s burn] I then got the scent of a chemical being sprayed, and in a short while fire and very dark smoke engulfed the whole place […] I hid in the waste pit behind the house for five hours, as I watched my entire house and the car destroyed.

On December 5, the army killed seven people in Meluf, including a 70-year-old man with a hearing impairment who was burned inside his neighbor’s home. A relative of the victim said he was inside the house when the military broke into the neighborhood that morning: “[They] started shooting and burning, everyone ran away. He didn’t hear anything. He was alone. The house was burned and he was inside.”

In its March 22 letter to Human Rights Watch, the government of Cameroon wrote that the military operation in Meluf was conducted to avoid a massive jail break “planned by terrorist groups in order to boost their ranks.”

This violence continued into 2019. On January 23, a mix of soldiers, BIR, and gendarmes raided Rohkimbo, a neighborhood in Kumbo, searching for separatists. Witnesses said that security forces started shooting indiscriminately. Frightened by the gunfire, some residents sought refuge around a house. Security forces targeted the house and several bullets penetrated the walls, killing a 1-year-old girl, and injuring her mother and brother.

In its March 22 letter to Human Rights Watch, the government of Cameroon wrote that between January 21 and 22, following clashes between the security forces and the separatists, a house where the separatists had hidden burnt because of the presence of illegal petrol products. It added that despite no civilian casualty was reported in the burning incident, an investigation by the gendarmerie is underway.

Between February 16 and 19, in what appears to be retaliation against residents perceived to be sympathetic to separatists, security forces torched about 60 homes and shops across Kumbo. Satellite imagery obtained by Human Rights Watch shows that buildings were destroyed in three main areas in Kumbo and nearby villages. The actual number of buildings destroyed is most likely higher because of limitations in the resolution of the satellite imagery.

Bole Bakundu (South-West region)

On February 6, BIR soldiers stormed the Bole Bakundu market, killing up to 10 men, said six witnesses and four residents who live nearby and who spoke to witnesses and people who were injured. Community members said they believed that security forces were retaliating against civilians accused of collaborating with the separatists. Witnesses said that soldiers arrived at the market around 8:30 a.m. and started shooting indiscriminately. A 34-year-old woman who was at the market with her children that day said: “Many people were in the market. I saw the BIR shooting men like dogs, randomly. Some were even asked by the BIR to lift up their hands up as they shot at them.”

Residents confirmed that separatists operate near the village and had built a roadblock in “Mile 15” in Bole Bakundu on February 3.

Attacks on Health Personnel, Facilities

Local and international media and human rights organizations have reported that both security forces and armed separatists have killed health professionals and targeted health facilities since the crisis began in the Anglophone areas. Human Rights Watch documented that security forces have killed at least two health professionals since August, including a pregnant nurse; gravely injured a nurse; and attacked three health facilities.

On January 18, soldiers shot dead Fomonyuy Ornella Nyuymingka, a 28-year-old nurse who was seven months pregnant, while she was on her way to work in Kumbo (North-West region). A witness who rushed her to the hospital said that soldiers shot her from about 80 meters, despite her visible medical attire. Her killing caused an outcry in Kumbo, as hundreds gathered to mourn her, brandishing signs asking belligerents to stop targeting medical staff. A medical source said the nurse had been shot in the chest, making it impossible for doctors to save her or the baby.

In its March 22 letter to Human Rights Watch, the government of Cameroon wrote that the security forces conducted a joint operation at “a place of assembly of armed terrorists” in Mveh, Kumbo on January 18, following which there was exchange of gunfire between the security forces and the separatists. A report of the operation “revealed no civilian casualties.” The government asserts that the nurse was not in the direct fire area of the army. Nonetheless, an investigation by the gendarmerie into this case is underway.

In November, the military destroyed and looted property belonging to medical personnel of the Banso Baptist Hospital in Kumbo, North-West region, including computers and motorbikes. The military shot a female nurse from the same institution wearing her medical uniform at close range as she was on her way home in Kumbo in December. In early March, soldiers broke into the same hospital again, looking for a wounded separatist whom they suspected was being treated there. On February 17, soldiers looking for wounded separatists broke into the Shisong hospital (Kumbo, North-West region) and fired several shots in the air.

Sexual Violence

Human Rights Watch documented three cases of sexual violence by security force members. Two women and one girl from a locality (name withheld) in the North-West each said that BIR soldiers raped them in January. Aid workers in the North-West and South-West regions expressed concerns that similar cases go unreported.

“Sarah,” a 22-year-old mother, said that two BIR soldiers raped her at home in early January: “I was in the kitchen with my baby and a neighbor, [when] two military with BIR uniforms entered my home.” When she couldn’t provide information on the whereabouts of the separatists, one soldier threatened to kill her: “He put me on the ground while the other was holding my hands. He raped me. Then, the other raped me too. After that, one asked me whether he should be giving me money, around 5,000 or 10,000 CFA (US$8 or 16). The other said: ‘We should just go, go fast.’ So, they left.”

Sarah went to a medical facility for post-rape treatment the same day. However, she said that she did not report the sexual assault to the authorities out of fear and shame of stigma. She said she has experienced anxiety and insomnia since the rape and has sought support from a religious organization.

In another case, also from January, three BIR soldiers raped a 23-year-old woman and a 17-year-old girl in the same home. The victims, who were neighbors, said that the soldiers arrived around 8:30 p.m. and accused them of hiding separatists. The soldiers then raped them in front of two children. The soldiers also attempted to rape another woman in the same home. She said:

The soldiers were dressed in the BIR uniform. One took me outside and asked me to undress. I begged him to let me go. He said he will kill me if I don’t take off my clothes. He put his gun between my legs and tried to force his way into me. I resisted. My baby was crying loud. I asked the BIR to let me check on the baby. He accepted. That’s how I was spared. The baby saved me, but when I entered, I saw my sister and my neighbor on the floor. They had been raped by the other two soldiers. When [the soldiers] left, we cried.

The victims went to a health center where a nurse gave them post-rape treatment.

Human Rights Abuses by Armed Separatist

Kidnappings

Human Rights Watch interviewed nine people who said that separatists kidnapped them between November and January and documented three cases since October in which groups of students and teachers were kidnapped together in the North-West and South-West regions. Armed separatists have also targeted national and international aid workers, curbing humanitarian work in the crisis-affected areas. Media reports indicate that at least 350 people have been kidnapped for ransom since October 2018, including 300 students. Human Rights Watch has been able to confirm several of these cases.

Nearly all were released after relatives or school authorities paid ransom. Kidnappers have demanded between 100,000 CFA and 1,500,000 CFA ($170 and 2,500) per person and often followed a similar pattern of blindfolding, beating, and threatening them. The kidnappers then ordered the victims to call their relatives, friends, or employers to beg them to pay for their release.

A 33-year-old man described being kidnapped by members of the armed separatist group Ambazonia Defense Forces (ADF) and taken to their camp near Teke (South-West region) in early December. He saw the separatists wearing ADF t-shirts, and recognized “General Ivo,” a widely known separatist commander killed later that month. He said he spent five days in the ADF camp, then was released without any ransom payment: “I had to use the toilet and I asked to be taken out of the room where I was kept. They accepted, but said that I had to pay. I discovered that the payment was beatings. They beat me up on my back with cables.”

In all the cases documented, relatives of the hostages did not inform authorities about the kidnapping, either because they believed they would get no assistance or because they feared that any rescue operation would endanger their loved-ones.

Abductions of Students, Teachers

Since early 2017, separatists have consistently targeted school buildings and threatened education officials and students with violence if they did not comply with separatist demands to boycott schools. They have also used schools as bases, deploying fighters and weapons in and near them, including in Koppin village (Mezam division), Tenkha village (Ngoketunjia division), and Mbuluf (Bui division).

Separatists abducted 20 children and a teacher from the Lord’s Bilingual Academy in Kumba, South-West region, at about 9 a.m. on November 20. They were forced to walk into the bush for over four hours until they neared Difang. Three children were taken home the same day following a rescue operation by gendarmes. The others escaped during the rescue operation and found their way home with the help of a local resident.

Separatists kidnapped six children and a teacher on December 14 near Nkwen, North-West region. They all appeared in a video filmed by their kidnappers while singing the Ambazonia anthem. Human Rights Watch spoke with two relatives who confirmed that their children were kidnapped on their way home from school, around 4 p.m. They said the children in the video attended at least three schools in the area. All were released six days later following a ransom payment. The father of one of the children said that two separatists on a motorbike kidnapped his son and a female classmate:

The kidnappers stopped them on the road and ordered them to climb on the bike. When they resisted, one of the kidnappers showed them a shotgun… They were blindfolded and taken to the [separatist] camp. There, they were beaten on the soles of their feet. They were told that they were taken because they were attending school and that schools had to be closed.

Fuler Ayamba, the Secretary General of the Ambazonia Defence Forces (ADF), said in a March 14 letter to Human Rights Watch that the ADF “impresses strict discipline on the fighters” under its control. With regard to allegations of large-scale kidnappings by the armed separatists, Ayamba said that these were carried out by the government to tarnish the image of ADF and other armed separatist groups or by opportunists seeking to exploit the crisis for their own gain. The ADF denies it was involved in any kidnappings around Teke. Human Rights Watch cannot confirm that ADF has command control over all fighters in their zones.

Sako Samuel Ikome, acting president of the Ambazonia Interim Government, a separatist group, said in a March 19 email that some members of the Ambazonia Restoration Forces have committed abuse and have been sanctioned by the Interim Government. Ikome denied that the group was involved in any kidnapping of students in Nkwen. He blamed violence in the regions on bandits and government-sponsored groups.