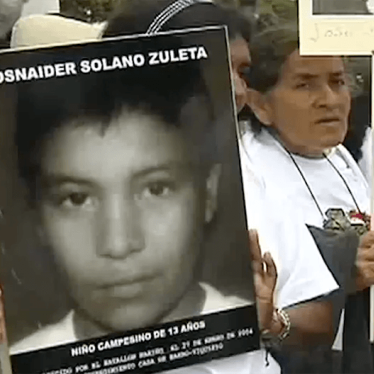

The commanders of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) have often tried to whitewash the guerrillas’ role in recruiting children and other serious human rights abuses, including sexual violence and forced abortion. But Colombia now has a chance to challenge that narrative and expose the truth.

On March 6, the Special Jurisdiction for Peace – the judicial system created by the peace accord to try abuses connected to the armed conflict—opened an investigation of the guerrillas’ recruitment of children, as well as abuses, including rape, that children suffered in their ranks.

In 2015, commanders said that the group had “under no circumstance recruited children, or anyone else, forcefully.” Reports about forceful recruitment were “propaganda,” they said, to “delegitimize” the guerrillas. More recently, last December, Marcos Calarcá, a former FARC commander, told reporters “no one” had ever been forced to join the FARC.

This is a lie. It’s true that many children joined the FARC to escape poverty, deprivation, and lack of affection and family support. But Human Rights Watch research has shown that the FARC also forcefully recruited children.

“They captured me and tied me up,” a 12-year-old boy told us. “I did not want to join, but I was convinced that if I did not go with them, they would kill me.” In many other cases, children were deceived—often lured with bogus promises of money—and threatened with execution when they tried to leave. A 2016 report by the Attorney General’s Office noted that in 53 percent of FARC child recruitment cases under investigation, the children were recruited by deceit or force.

The guerrillas’ argument also misses the point. Under international humanitarian law, recruiting children under age 15 into an armed group—a regular FARC practice—is a war crime, regardless of whether the children “volunteered” to join. Likewise, the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child, which Colombia ratified in 2005, prohibits the recruitment of children under 18 by non-state armed groups “under any circumstance.”

FARC commanders have also tried to whitewash sexual abuses against women and girls in their ranks. These included rape, forced sterilization, and forced abortion. In 2015, for example, the group said there was “no room for violence against women in the FARC ranks.” Yet Human Rights Watch research shows that male FARC commanders often used their power to coerce girls into service as their sexual partners. And the Attorney General’s Office, in the 2016 report, notes receiving reports of almost 100 cases of rape of women and girls in the FARC ranks.

FARC commanders forced girls as young as 12 to use contraception, our research shows, and to have abortions if they got pregnant. Decisions about pregnancy and abortion should be made by women or girls without interference, pressure, or coercion.

One girl told Human Rights Watch that a 35-year-old FARC commander started a sexual relationship with her when she was 12. Two years later, she became pregnant. Despite the coercive nature of the relationship, she wanted to continue the pregnancy, but she was denied that choice. Under the pretext of a health check-up, FARC members subjected her to a forced abortion against her will and without her knowledge. “The worst thing is that you can’t have a baby,” she said. Many other girls suffered similar abuses.

The guerrilla group insists it only “promoted the use of contraceptives,” while commanders “explained” to women entering the ranks that “pregnancies were not allowed.” “Pregnant women had to make the decision to continue a pregnancy and leave the ranks, or to end their pregnancy,” former guerrilla commanders said in a 2017 statement. Their argument implied that pregnant women could decide freely to leave the ranks of an armed group and find safety. This narrative ignores the reality that many women and girls were forced into FARC’s ranks and then subjected to sexual violence, forced pregnancy, and forced abortion. They faced coercion and abuse at every turn.

The peace accord makes a tempting offer to FARC commanders involved in these heinous crimes. If they confess and acknowledge their responsibility, they can avoid prison time. They can serve alternative sentences, completing community-service tasks. Yet the deal requires commanders to tell the truth. Otherwise, they risk serving long prison sentences. Children recruited and abused by the FARC deserve justice.