Introduction

“When the killings began, my teacher asked me to stop coming to school.” - “Juma”, July 2017

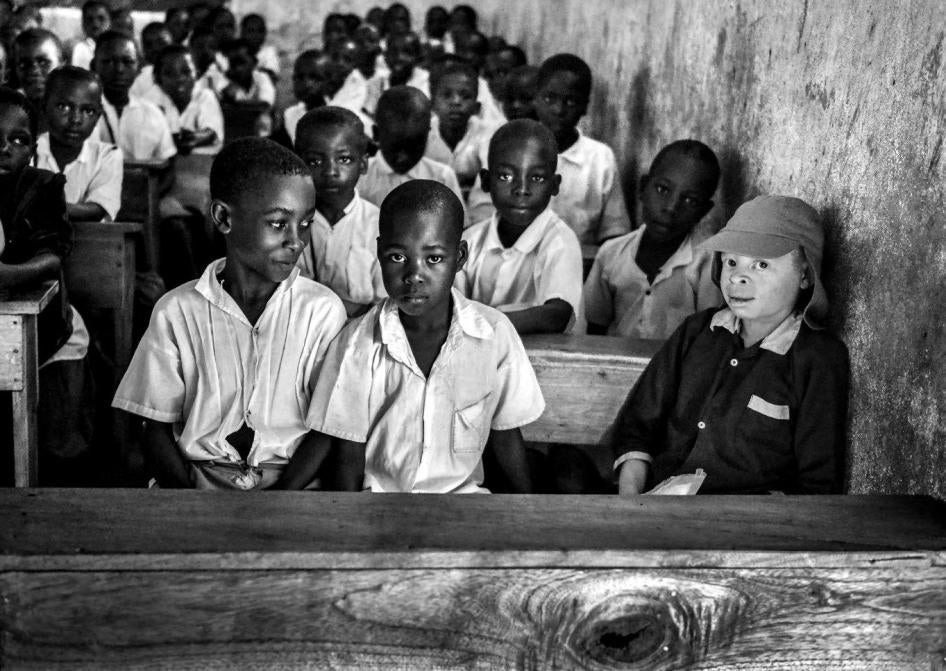

Juma was 16 years old when Human Rights Watch interviewed him in July 2017. Seven years earlier, his life had been turned upside down because he was born with albinism.

Orphaned since the age of six, Juma lived with his siblings and his grandfather, a heavy drinker, in a rural area of Northwest Tanzania, south of Lake Victoria. “Sometimes, when he was drunk or talking about me with his mates, my grandfather would call me ‘Chinese’ or ‘Mbolimbwelu’ which means ‘white goat’. I felt very bad,” Juma said.

As a wave of ritual killings and amputations of people with albinism, especially children, began to spread in Tanzania in the late 2000s, the country’s government set forth measures designed to ensure the physical safety of children with albinism, including by establishing “temporary holding shelters,” special boarding schools dedicated to the protection and education of children with albinism.

To populate these establishments, the government directed district and community leaders to bring children with albinism to the shelters. While there is no official data on the subject, a local activist estimated that around a thousand children from all over the country have been placed in shelters. As a result of the government’s measure, Juma’s regular school did not welcome him anymore.

But Juma’s grandfather did not send him to a shelter. Instead, he forced him to work in the field, taking care of his cattle. “I was told to stop school because they were worried, but then in the farm there was no security. It felt unjust because my brothers and sisters went to school, but I had to work,” Juma told Human Rights Watch.

Many children with albinism in Tanzania share similar stories of hardship. The “temporary holding shelters” strategy introduced by the Tanzanian government in the late 2000s may have contributed to a decline in the number of physical attacks, but Human Rights Watch observed that it led to the emergence of additional challenges.

In July 2017, Human Rights Watch interviewed 13 children and young people with albinism, aged 7 to 18 years old, and 26 other people, including family members, education professionals and nongovernmental organizations in the Mwanza, Shinyanga and Simiyu regions of Tanzania. There, we found that Tanzanian government policies designed to protect children with albinism incidentally had a negative impact on their rights to family life, an adequate standard of living and inclusive education. In order to protect their privacy and shield them from potential repercussions, the names of most interviewees referred to hereafter have been changed.

While the Tanzanian government appears sensitive to these concerns, it should now intensify efforts to reinsert children with albinism into their communities and provide them with inclusive education, while continuing to investigate and prosecute those responsible for attacking children with albinism. By doing so, Tanzania has an opportunity to emerge as a strong African leader in ensuring the safety, inclusion and dignity of people with albinism, as outlined in the Regional Action Plan on Albinism in Africa, the first-ever continental strategy to address violations against people with albinism, adopted in 2017.[1]

What Is The Best Interests of the Child Principle?

The Best Interest of the Child principle derives from the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. It requires state parties to prioritize the interests of the child in any action that may impact them. This includes taking into consideration the child’s own views and desires, his identity, his need for care and development and his right to a safe family and community environment. These factors should be considered altogether and balanced against one another if in contradiction. State intervention should be based on individual assessments of the particular child whose situation requires it.

Recommendations

To the Government of Tanzania:

- Increase public sensitization efforts aimed at dispelling deadly and discriminatory myths about albinism, notably through workshops and public service announcements on radio and television, particularly in rural and isolated communities.

- Ensure that all teachers in the public education system are trained to adequately provide for the specific needs of children with albinism.

- Ensure that resources are at the disposal of schools to meet the specifications needed of children with albinism, notably by providing for textbooks and exams with larger fonts and assistive devices to read the blackboard.

- Pursue efforts to promote the safety of people with albinism by investigating threats and crimes against people with albinism and holding those responsible to account.

- Work with parents and communities to ensure the safe and orderly reunification of children with albinism with their families, with the goal of progressively dismantling the temporary holding shelters.

To International Donors:

- Support projects dedicated to sensitizing the Tanzanian public to albinism and training teachers to provide for the specific needs of children with albinism in public schools.

- Support the Tanzanian government in reuniting children with albinism with their families and ensuring their return to a safe, inclusive community.

Albinism in Tanzania

People with albinism usually have a paler, whiter appearance than their relatives. The deficit of melanin can also result in low vision and an increased vulnerability to sun’s ultra-violet radiation. Consequently, people with albinism living in Sub-Saharan African are about 1,000 times more likely to develop skin cancer than the general population.[5]

As noted by the United Nations Independent Expert on the enjoyment of human rights by persons with albinism, “The complexity and uniqueness of the condition means that their experiences significantly and simultaneously touch on several human rights issues including, but not limited to, discrimination based on color, discrimination based on disability, special needs in terms of access to education and enjoyment of the highest standards of health, harmful traditional practices, violence including killings and ritual attacks, trade and trafficking of body parts for witchcraft purposes, infanticide and abandonment of children.”[6]

In many parts of East Africa, people with albinism are targeted for their body parts, which some believe hold magical powers and bring good fortune. Traditional healers and “sorcerers” have over the years claimed that people with albinism are “ghosts” who never die but merely disappear. In 2009, the International Federation of the Red Cross reported that a senior police officer in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania’s economic capital said that the body of a person with albinism could fetch up to US$75,000.[7]

Over the last decade, Under the Same Sun, a Canadian non-governmental organization working to empower people with albinism, estimates that over 200 people with albinism, many of them children, have been killed in Africa or had their body parts amputated. In Tanzania alone, the group reported that at least 76 people with albinism were killed since 2006.[8] NGOs and local groups reported that criminals have stolen bones from the exhumed remains of people with albinism.[9]

The last reported killing, in February 2015, took place in the region of Geita, in Northwest Tanzania, when men abducted a one-year-old baby with albinism from his mother and “hacked [him] to death.”[10] The men were said to have hit the mother with a machete when she refused to hand over her child, an activist who was with her when she woke up at the hospital told Human Rights Watch.[11]

Faced with increased international scrutiny at the end of the 2000s, Tanzania began to mobilize resources to fight off traffickers and protect people with albinism. Local organizations told us that since 2007, hundreds of children were removed from their families, sometimes with no consultation or consent, and placed in shelters where they were effectively isolated from society.[12]

According to activists who spoke to Human Rights Watch, orders from the government to protect people with albinism were enforced by district commissioners, who oversee security in their respective districts.[13]

“There is an order from the district that says that if anything happens to [a] child with albinism, local leaders would be responsible. It something happens, the whole community will be suspected,” the manager of a local organization working with people with albinism told Human Rights Watch.[14] “Because no one wants trouble in their backyard, there was a big push from the communities to send the children to the shelters.”

The Tanzanian government also moved to combat impunity for ritual crimes, notably by investigating, arresting and prosecuting those who attack or sponsor attacks against people with albinism. In 2015, the Tanzanian government announced a ban on witchdoctors, which came out of a special joint task force between the police and the Tanzanian Albinism Society. As reported by the BBC at the time, then Home Affairs Minister Mathias Chikawe declared there would be a nationwide effort to "arrest them and take them to court" if witch doctors continued their practices.[15] Over 200 suspects, including some allegedly involved in killings of people with albinism, were reportedly arrested by the authorities.[16]

Ten years after the wave of killings and attacks began, these appear to have decreased because of Tanzania’s protective measures and stronger response to ritual crimes and attacks against people with albinism. The temporary holding shelters, however, remain. “The shelters were emergency, temporary solutions. But 10 years is not temporary anymore,” an activist for the rights of people with albinism told Human Rights Watch.[17]

Under international human rights law, children with albinism have the right to live in a family environment. Local NGOs are now making efforts to reunite children and families.[18] The Tanzanian government should do more to reunite families, to combat stigma within communities and ensure that family caregivers have the financial and social support they need to care for these children.

The government’s response should be guided by the best interests of the children involved, and balance the child’s protection and safety with the preservation of the family environment and the enjoyment of other rights. This is particularly important as the government has begun to send some children from the shelters back to their communities.

Key Challenges

Separation from the family and movement restrictions

Most of the 13 children and young adults with albinism Human Rights Watch interviewed described how the killings and the ensuing protection measures implemented by the Tanzanian government separated them from their families.

While in many cases, separation was a decision of the parents, five children said they were ordered to go to a shelter or boarding school by government officials (police or district education officers), with no regard for their parents’ consent. Human Rights Watch was not able to confirm this assertion from their parents. Once in the shelters or special boarding schools, the children’s freedom of movement was severely curtailed on security grounds.

Marco, an 18-year-old man with albinism, described to Human Rights Watch how his father had been obliged to let him go to the shelter: “When the killings and attacks happened, the government moved me to the Buhangija temporary shelter (Shinyanga region). Police officers came home and spoke to my dad but he refused to take me to Buhangija immediately because he wanted to find out more about it first. The first time, the police left without problems. The second time, they left with me.”

Augustin, a 14-year-old teenager from Shinyanga who was attacked by criminals who cut his left forearms and fingers on his right hand when he was four-year-old, said the district education officer took him to the shelter when he was seven or eight. “He picked me up at a bus stand. At first, no one explained to me why I was being taken there. I was sad at the beginning because I missed my parents. It felt like a punishment. Now, I understand it was to protect me from bad people,” he told Human Rights Watch.[19]

The mother of Victoria, a young woman with albinism from Shinyanga region who stayed for three years in Buhangija, confirmed that parents did not have any choice but to let their children go: “The government wrote a letter to the school Victoria was attending giving notification that children with albinism should be sent to Buhangija [shelter]. We were given a specific date and time by which she had to be there, which was two days later.”

Victoria’s father added: “When the government said we had to bring Victoria to Buhangija, I didn’t know why. There was security here…. But I had to accept the order. I don’t know what would have happened if I had refused.” [20]

NGOs that promote the rights of people with albinism also reported pressure by the government on local schools and the community to send children away to the shelters, by threatening to hold community leaders and members accountable if a child who remained at home was attacked.[21] “For communities, having a child with albinism among them felt like a burden – because you have to provide protection – so the shelters were a good solution to get rid of that burden. You don’t have to respond to police enquiries if something happens,” a national advocate for the rights of people with albinism told Human Rights Watch.[22]

In addition, parents of children with albinism and organizations working with people with albinism told Human Rights Watch that regardless of whether children had been voluntarily or involuntarily placed in shelters, once they were under the protection of the state, they were no longer allowed to go home – even for vacations – without a letter from the village chairperson, approved by the district commissioner, guaranteeing the area’s safety.[23] An NGO worker explained the process to Human Rights Watch:

The parents [must] first get a letter from the chairperson of the village and then send it to the district commissioner. The chairperson’s letter should say that the area is safe, that we know the child with albinism is visiting the parents. Without the chairperson’s letter, the district commissioner cannot issue his own letter. Some parents complain and say that they have the right to take the children home. But they generally understand.[24]

Severin, a 14-year-old boy with albinism, said he never went home on vacation while he lived in the shelter. “Once in Buhangija [shelter], we were told we needed a letter to be allowed to go home. My parents didn’t try to get the letter. I felt bad not to be with my family during the vacations because I missed them,” he said.[25]

The parents of Victoria, a young woman with albinism who stayed for three years in Buhangija, who have university degrees, said it was easy to obtain such a letter from the authorities. “When the parents are bringing the letter, it assures the school that there is full security in the family and in the village [for children with albinism],” the mother said. “We wouldn’t have been allowed if we had tried to bring [our daughter] home for good. It was impossible to come out of Buhangija [shelter] without permission. There was full security.”[26]

A representative of an international NGO sponsoring the education of children with albinism told Human Rights Watch that these restrictions also apply to children who have been moved out of shelters and into private schools under their sponsorship program.[27]

As a result of the government’s restrictions, some children had not been home for several years, and some were no longer in contact with their family. In one case, Lucy, a 12-year-old girl with albinism, told Human Rights Watch at the time of the interview that she had not seen her mother in two years and did not know where her family was:

I was 6 years old when I got to Mitindo [shelter in Mwanza]. My mother brought me there because she saw the thieves [people attacking children with albinism] and so she took me to the [shelter]. I was left there alone by my mother and I felt sad because she said she’d come back but did not. She came back only once I went [to a private school, where I am being sponsored by an international NGO] in 2015. She came only for one day to ask who was paying my school fees and asked whether they could pay for my brothers too. I don’t know why she hasn’t come back. We don’t get to speak on the phone. I don’t have her number. So I don’t know about my mother and brothers right now.[28]

According to representatives of local organizations working with people with albinism, another reason why some children placed in shelters no longer see their family is because their parents left no records of where they came from, and tracing the family after several years is difficult.[29] “When some parents brought their children to the shelters, some didn’t leave any contacts and in other cases they did but the phone numbers don’t work,” a local NGO worker told Human Rights Watch.[30] A staff member of another NGO said the temporary holding shelters had become akin to orphanages: “Parents took advantage to drop their kids there. Some children with albinism have been there for four or five years now without seeing their parents.”[31]

The separation from family exerts a heavy emotional toll on young children with albinism. Peter, an 18-year-old man who stayed at the Buhangija for eight years, said his brother was the only one visiting him. “I didn’t want to come [to the shelter]. I was too young. I used to cry all the time. I was a child, I missed my mother, my grandmother and my sister,” he told researchers. “Only my brother would come to visit. I did speak with my mother however, maybe once a month by phone. I felt good talking to her but I missed her.”[32]

Despite the difficulties children with albinism face in the shelters, some, including Severin, said they saw advantages in living among other people with albinism: “My parents did not come to visit at Buhangija. But it was good to be with other children with albinism because we felt we had a right to stay in the world.”

To protect children with albinism from physical attacks, a number of shelters and boarding schools have enforced drastic security measures that deprive children of their freedom of movement.

In July 2017, Human Rights Watch visited Buhangija, a former boarding school for students with disabilities transformed into a temporary holding shelter for children with albinism in 2009. At the time of the visit, 226 children were living in the shelter, out of whom 142 were children with albinism (the others were deaf or blind children attending the inclusive school located next to the shelter). At the shelter, Human Rights Watch researchers observed a barren compound made up of five dormitories surrounded by tall walls topped with barbwire.[33] Children with albinism who attend class walk about 100 meters to the school. The rest of their free time is spent within the compound, which has no recreation space or trees to provide for shade, useful in helping people with albinism shield themselves from the sun.

“My first impression of Buhangija was that it was so difficult because we were staying in [the shelter] for the whole day and I’m a very mobile person. So I first felt very bad but as days went by, I got used to it,” Marco, an 18-year-old who left the shelter in 2017 told Human Rights Watch.[34]

The principal of a secondary boarding school that caters to children with and without albinism in Mwanza region told Human Rights Watch that the movement of children with albinism is restricted even beyond the temporary holding shelter, and in the case of his school, because it lacks resources to adequately protect them outside the compound: “The main challenge with people with albinism is protection and safety,” he explained. “I’ve been asking since last year for one district policemen to be on site at night but there isn’t enough [district]money to do that. So, we talk to those students and discourage them from walking around alone, especially at night.”[35]

A 15-year-old girl with albinism attending that secondary boarding school said they are not allowed to leave the dormitories: “The environment here is not good. We are not allowed to stay outside because the school doesn’t have enough security. Classes usually finish at 2:15 p.m. and we have to be in our dormitories by 2:40 p.m.”[36]

NGOs have reported that children with albinism living in these shelters are progressively being sent back to their communities.[37] While this is important progress, it is essential that the process of reinserting children in their communities complies with the best interests of the child principle. Authorities should ensure that the views of children and their families are taken into account, that children have access to education in their community, and that the community has protection systems in place.

Such consultations did not take place in the case of Mariam, a seven-year-old girl from Simiyu region, who was reunited with her 85-year-old grandmother. “After she was removed from Buhangija, the government forced me to take care of Mariam because her mother and father are not providing for her, “recalled the grandmother.” This happened without the government consulting me beforehand…. They just dumped the child on me.”[38] Mariam does not attend the local school because, her grandmother said, she could not afford to buy textbooks.

Stigma and bias in the community

Eight children with albinism interviewed by Human Rights Watch recounted how they experienced stigma and bias in their communities, including name-calling.

Josefina, a seven-year-old living with her grandparents in the Shinyanga region, for example, said other children call her “Mbuliwmelu,” which means “white goat” in the local Sukuma language. “When that happens, it makes me feel sad and very angry, but I stay silent,” she said.[39]

In the Simiyu region, the grandmother of Mariam, a seven-year-old young girl with albinism, said Mariam frequently faced similar experiences:

Most people have a negative perception of Mariam because of her color. They don’t even want to welcome Mariam in their home. If they see her, they’ll see her colour and will see that if she spends too much time in the sun she has sores. If she plays, they fear blood will come out of her. They call her “Mbulimwelu”. Mariam is always sad when they call her like that, and sometimes she locks herself in the house and starts crying. In those cases, I just leave her alone.[40]

In some cases, parents have rejected or attacked their own children. Twelve-year-old Lucy, for instance, now lives at a private boarding school after receiving a scholarship from an international NGO. Choking on her tears, she said her mother told her that her father abandoned her prior to sending criminals to try and kill her: “My mother told me that my father refused me. I don’t want to go back [to my hometown] because it is my father who sent the thieves to get me.”[41]

Despite efforts by the government of Tanzania and NGOs to sensitize the general public in recent years, progress remains fragile, especially in rural areas, where people with albinism continue to face stigma and the rejection of their community and, at times, their own families. This can lead to poor self-esteem among young people with albinism, and difficulties in finding work opportunities later in life. An 18-year-old man with albinism told Human Rights Watch in Shinyanga region that he thought people like him have a harder time at finding work: “My life would definitely be different if I was not a person with albinism. If you have a black skin, you have many more opportunities. You can do the physical work, whereas person with albinism have to be careful because of their skin.”[42]

But, as the parents of four children with albinism pointed out, not all communities and families reject children with albinism. “When I had my first child with albinism, I was happy and thought this was normal. My family was happy too and if they weren’t, they didn’t let it show,” their mother said.[43] “It is the choice of God. God is giving. We should agree with them, be close with them,” their father added.[44]

Barriers to education

“People with albinism don’t get education,” a community organizer with albinism told Human Rights Watch.[45] “Firstly because of their low vision. Teachers don’t know how to deal with that. Secondly because [of lack of] interaction [with others]. There is teasing in school. People with albinism face a lack of interaction with local community. People see us as bad people. They see us as people who can’t contribute because of our bad education or lack of education,” he added.[46]

Ensuring a free, safe and dignified access to education is key to upholding the fundamental human rights of people with albinism and to combatting the stereotypes and stigma that continue to expose them to mistreatments and fatal risks.

Children with albinism face a range of barriers impeding their access to education.

Many families of children with albinism for instance are unable to enroll them in school because they lack sufficient income, or fear that having them walk to school may expose them to dangers.[47] The grandmother of Mariam, the seven-year-old girl with albinism, said she is ready to go school but that she doesn’t have the resources to send her. “I wish for Mariam to become a doctor or a teacher. I don’t want her to be a wife. But it costs money to buy books and everything.”[48]

Children with albinism may also face health risks at school due to their sensitivity to the sun. Laura, a 15-year-old student at a public secondary school, told Human Rights Watch that despite efforts to train teachers on the needs of children with albinism, the school still put the health of children with albinism at risk: “This school is not good. They force us to do activities in the sun. Teachers can also punish you if you say you can’t do activities in the sun. They caned me three times and it was very painful.”[49]

In addition, children with albinism do not always get the inclusive education they should be entitled to. In that respect, the existence of the temporary holding shelters and other special boarding schools, while providing safety and an opportunity to attend classes, promotes segregation and denies children the opportunity to learn with their peers without albinism and to feel included in their communities. As 12-year-old Lucy explained to Human Rights Watch, “It was not nice to only be with children with albinism because we stayed without difference – we must mix.”[50]

Children interviewed by Human Rights Watch also said that schools sometimes fail to provide children with albinism with appropriate accommodations for their low vision.[51] This would include assistive devices, such as magnifiers, enlarged printed material, writing in large letters on the blackboard, and seating children with albinism in the front of the classroom.

Gloria, a 14-year-old student with albinism who wants to become an engineer and build airplanes said she had different experiences in public and private schools: “Before, I was going to a public school. I didn’t like it there because there was no good care. In class, the teachers would be writing with small letters on the blackboard. I’d ask them to make the letters bigger, but they’d say that they can’t,” she told Human Rights Watch. “[The private school] was better. They wrote with big letters on the board – it was easier for me to follow the classes and get good grades.” [52]

Some public schools are taking positive steps. The principal of a Mwanza region public secondary boarding school that caters to the general public as well as to several children with disabilities and children with albinism told Human Rights Watch: “There is no segregation. All students are taught together. We have many special education teachers and they are all trained by the government. I insist that children with albinism sit at the front row and that the teachers write with big letters on the blackboards and that exams and other exercises are printed with big font for them,” he said. Yet, the resources are scarce: “We get some equipment from the ministry, but not enough. We have no monoculars [to help children with albinism see the blackboard], for instance.” [53]

Lawrence is a shy nine-year-old boy who attends public school and his father is very proud of him. “When we took him to school for the first time, teachers were very aware of albinism, maybe they had been trained,” Charles said.[54] “The only challenge Lawrence faces is his vision. Sometimes he has difficulties reading the blackboard [but] he gets support from the teachers and sometimes they explain or move him to the front. Lawrence does very well at school and sometimes is at the first position.”[55]

It is important that all teachers be familiarized with the specific needs of students with albinism and that the schools be provided with adequate resources to ensure they can achieve their full educational potential. More efforts are also needed to sensitize family-members and communities about albinism, to ensure that children with albinism in Tanzania can thrive both inside and outside the classroom.

[1] Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, “Regional Action Plan on albinism,” https://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/Albinism/Pages/AlbinismInAfrica.aspx (accessed January 25, 2019).

[2] United Nations General Assembly, Report of the Independent Expert on the enjoyment of human rights by persons with albinism, Ikponwosa Ero, A/HRC/37/57/Add.1, January 18-March 23, 2018, para. 12, https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G17/364/15/PDF/G1736415.pdf?OpenElement (accessed January 25, 2019).

[3] Tanzania’s last national census took place in 2012; Ibid, para. 15.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Lekalakala, P., Khammissa, R., Kramer, B., Ayo-Yusuf, O., Lemmer, J. and Feller, L., “Oculocutaneous Albinism and Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Skin of the Head and Neck in Sub-Saharan Africa,” Journal of Skin Cancer, August 12, 2015, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4549604/ (accessed January 25, 2019).

[6] Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, “Independent Expert on the enjoyment of human rights by persons with albinism,” https://www.ohchr.org/en/issues/albinism/pages/iealbinism.aspx (accessed January 25, 2019).

[7] International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, “Through albino eyes, The plight of albino people in Africa’s Great Lakes region and a Red Cross response,” 2009, p.5, https://www.ifrc.org/Global/Publications/general/177800-Albinos-Report-EN.pdf (accessed January 25, 2019).

[8] Under the Same Sun, “People with Albinism and the Universal Periodic Review of Tanzania,” undated, para 3, https://uprdoc.ohchr.org/uprweb/downloadfile.aspx?filename=2699&file=CoverPage (accessed January 25, 2019).

[9] AFP, “Albino attacks drop in Tanzania, but grave vandalism rises: NGO,” News24, November 16, 2017, https://www.news24.com/Africa/News/albino-attacks-drop-in-tanzania-but-grave-vandalism-rises-ngo-20171115 (accessed January 25, 2019).

[10] Nicola Bartlett, “Albino baby hacked to death in Tanzania's latest witchcraft related death,“ Mirror, February 18, 2015, https://www.mirror.co.uk/news/world-news/albino-baby-hacked-death-tanzanias-5185686 (accessed January 25, 2019).

[11] Human Rights Watch interview with community activist (pseudonym), Tanzania, July 2017.

[12] Human Rights Watch interview with representatives of three NGOs working in this field, names withheld, Tanzania, July 2017.

[13] Tanzania is a republic made up of 31 regions and 169 districts. Each district operates a security committee, headed by the district commissioner, in charge of enforcing laws.

[14] Human Rights Watch interview with NGO workers, names withheld, Tanzania, July 2017.

[15] BBC NEWS, “Tanzania bans witchdoctors over albino attacks,” BBC, January 13, 2015, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-30794831 (accessed January 25, 2019); David Smith, “Tanzania bans witchdoctors in attempt to end albino killings,” The Guardian, January 14, 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/jan/14/tanzania-bans-witchdoctors-attempt-end-albino-killings (accessed January 25, 2019). The practice of witchcraft has been against the law since the 1928 Witchcraft Act, https://mtega.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Witchcraft-Act-Cap18-as-amended-2009.pdf (accessed January 28, 2018).

[16] BBC NEWS, “Tanzania albino murders: 'More than 200 witchdoctors' arrested,” BBC, March 12, 2015, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-31849531 (accessed January 25, 2019).

[17] Human Rights Watch interview with community activist (pseudonym), Tanzania, July 2017.

[18] “Just Kids 2016/2017 - The girl with the white skin”, video clip, YouTube, February 13, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sQZgW8DUCs0 (accessed January 25, 2019).

[19] Human Rights Watch interview with Augustin (pseudonym), Tanzania, July 2017.

[20] Human Rights Watch interviews with A.Y. and Z.M. (pseudonym), the parents of Victoria (pseudonym), Tanzania, July 2017.

[21] Human Rights Watch interview with representatives of three NGOs working in this field, names withheld, Tanzania, July 2017.

[22] Human Rights Watch interview with community activist (pseudonym), Tanzania, July 2017.

[23] Human Rights Watch separate interviews with representatives of three NGOs working in this field, names withheld, Tanzania, July 2017; Severin (pseudonym), Tanzania, July 2017; and A.Y. and Z.M. (names withheld), Tanzania, July 2017.

[24] Human Rights Watch interview with NGO representative (pseudonym), Tanzania, July 2017.

[25] Human Rights Watch interview with Severin (pseudonym), Tanzania, July 2017.

[26] Human Rights Watch interviews with A.Y. and Z.M. (names withheld), parents of Victoria, Tanzania, July 2017.

[27] Human Rights Watch interview with NGO representative (pseudonym), Tanzania, July 2017.

[28] Human Rights Watch interview with Lucy (pseudonym), Tanzania, July 2017.

[29] Human Rights Watch interview with representatives of three NGOs working in this field, names withheld, Tanzania, July 2017.

[30] Human Rights Watch interview with a representative of one NGO working in this field (pseudonym), Tanzania, July 2017.

[31] Human Rights Watch interview with a representative of one NGO working in this field (pseudonym), Tanzania, July 2017.

[32] Human Rights Watch interview with Peter Mwanzi (pseudonym), Tanzania, July 2017.

[33] Human Rights Watch interview (pseudonym), Tanzania, July 2017.

[34] Human Rights Watch interview with Marco Ndimo (pseudonym), Tanzania, July 2017.

[35] Human Rights Watch interview with A.M. (pseudonym), Tanzania, July 2017.

[36] Human Rights Watch interview with J.P.M. (pseudonym), Tanzania, July 2017.

[37] Jesse Mikofu, “Children living with albinism start reuniting with families,” The Citizen, March 20, 2018, https://www.thecitizen.co.tz/News/Children-living-with-albinism-start-reuniting-with-families/1840340-4349742-105d5nv/index.html (accessed January 25, 2019).

[38] Human Rights Watch interview with K.M. (pseudonym), Tanzania, July 2017.

[39] Human Rights Watch interview with Maria (pseudonym), Tanzania, July 2017.

[40] Human Rights Watch interview with K.M. (pseudonym), Tanzania, July 2017.

[41] Human Rights Watch interview with Lucy (pseudonym), Tanzania, July 2017.

[42] Human Rights Watch interview with Peter Mwanzi (pseudonym), Tanzania, July 2017.

[43] Human Rights Watch interview with A.Y. (pseudonym), Tanzania, July 2017.

[44] Human Rights Watch interview with Z.M. (pseudonym), Tanzania, July 2017.

[45] Human Rights Watch interview with L.A. (pseudonym), Tanzania, July 2017.

[46] Ibid.

[47] Human Rights Watch interview with NGO workers (pseudonyms), Tanzania, July 2017.

[48] Human Rights Watch interview with K.M. (pseudonym), Tanzania, July 2017.

[49] Human Rights Watch interview with Laura (pseudonym), Tanzania, July 2017.

[50] Human Rights Watch interview with Lucy (pseudonym), Tanzania, July 2017.

[51] Human Rights Watch separate interviews with Gloria (pseudonym), Tanzania, July 2017; and Laura (pseudonym), Tanzania, July 2017.

[52] Human Rights Watch interview with Gloria (pseudonym), Tanzania, July 2017.

[53] Human Rights Watch interview with A.M. (pseudonym), Tanzania, July 2017.

[54] Human Rights Watch interview with Charles (pseudonym), Tanzania, July 2017.

[55] Ibid.