(Phnom Penh) – Survivors of acid violence in Cambodia are unlawfully denied free medical care and face pressure to accept inadequate settlements, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today. The Cambodian government should enforce its laws that require legal, social, and medical support to survivors of acid attacks.

The 48-page report, “‘What Hell Feels Like’: Acid Violence in Cambodia,” documents the use by private actors of nitric or sulfuric acid to inflict pain and permanently scar victims, and efforts by survivors to get justice and medical care. After several highly publicized acid attacks in Cambodia, the government in 2012 passed the Law on Regulating Concentrated Acid to curb the availability of acid used in attacks and to provide medical care and legal support to victims. Since passage of the law, acid attacks have dropped and regulations have reduced the availability of acid in the capital, Phnom Penh. However, Human Rights Watch found that many survivors of these attacks are unable to get adequate health care and meaningful compensation as the law requires, and that those responsible for attacks are rarely prosecuted.

“The Cambodian government took an important step with the Acid Law by making clear promises to survivors of acid violence,” said Brad Adams, Asia director at Human Rights Watch. “The government’s failure to enforce the law outside Phnom Penh, hold attackers accountable, or ensure adequate treatment and compensation for victims has left those promises unfulfilled – with consequences that last a lifetime.”

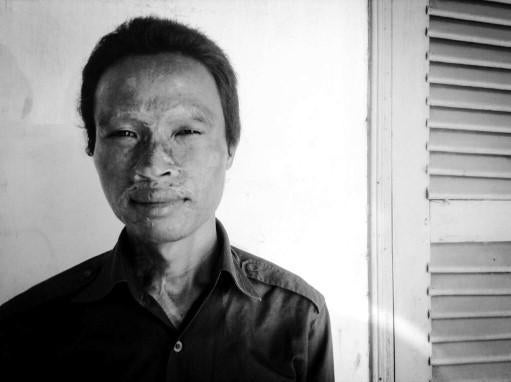

Human Rights Watch spoke with 81 people, including 17 survivors of acid attacks in Phnom Penh and Kampong Cham, relatives of survivors, lawyers, experts on acid violence, and motorcycle battery vendors and other acid sellers in Phnom Penh, Kampong Cham, and Tboung Khmum provinces.

While Cambodia’s Acid Law requires state hospitals to provide free medical care for acid attack survivors, no survivors interviewed by Human Rights Watch had received free treatment. Rather, they described being denied treatment until they could provide out-of-pocket payments or could show proof that they could pay. Even staff at the largest public hospital in Cambodia – the only one with a dedicated burn unit – were unaware that the law requires free treatment.

Survivors suffering from extremely painful acid burns face Cambodia’s notoriously strict regulations on opioid analgesics, including a seven-day limit for morphine prescriptions. No public hospitals outside of the capital carry oral morphine. As a result, access to pain relief for the rural poor is cost-prohibitive. Even in Phnom Penh, morphine, including oral morphine, remains scarce.

Perhaps the most infamous case of acid violence in Cambodia was the attack on then 16-year-old Tat Marina in 1999. Svay Sitha, then a 40-year-old deputy undersecretary of state in the Council of Ministers and a close aide to Prime Minister Hun Sen, posed as an American businessman and, Marina said, verbally and physically threatened her to maintain a relationship with him. When Sitha’s wife, Khoun Sophal, learned of the relationship, she hired men to beat Marina unconscious and pour nitric acid on her face. No one was ever prosecuted for the attack – even though it happened in daylight in a crowded public market and assailants left behind identification – and Marina never received any compensation. On September 6, 2018, Hun Sen promoted Sitha to minister delegate, the top cabinet-level advisor to the prime minister.

Most of the acid survivors interviewed for the report have not obtained any justice. Several said government officials pressured them to accept an inadequate settlement out of court. Of the handful of cases that have made it to court, few have resulted in a conviction, and fewer still in the people convicted serving out their sentence. Human Rights Watch is not aware of a single survivor interviewed who received any compensation through the court system, despite provisions under the Cambodian civil and criminal codes entitling victims to damages.

The Cambodian government should prohibit informal financial settlements in criminal cases and make the obstruction of justice a criminal offense, Human Rights Watch said. Such obstruction should include improperly intervening with police, officials, judges, or prosecutors. Cambodia’s Anti-Corruption Unit and Ministry of Justice should urgently finalize the long-promised draft victim and witness protection laws.

“The Cambodian government should explicitly communicate to all public hospitals the legal requirement to provide free treatment to victims of acid violence, and the government’s obligation to reimburse hospitals for the costs,” Adams said. “The government should update the regulations on opioid analgesics to ensure that opioid pain medications are both available and accessible for those who need them, to spare acid attack survivors a life of excruciating pain.”