Summary

Sitting on a thin mattress on the floor of their home in a Phnom Penh slum, 3-year-old Molita delicately touches the scars that cover her mother’s back. In November 2014, when Molita was an infant, the owners of a neighboring market stall attacked her mother, Moung Sreymom, with highly concentrated acid. They doused nearly half her body, leaving penetrating burns covering Sreymom’s back, arms, legs, and half her face, melting off her right ear. As the acid continued to seep into her skin for days after the attack, Sreymom, then two months pregnant, had a miscarriage. Sreymom’s body had largely shielded Molita, who was with her at the time, from the bulk of the attack, but two burn scars run down Molita’s face—just missing her right eye.

Human Rights Watch spoke with Sreymom in June 2015 and again in May 2017. She described not only the unrelenting physical and emotional pain that she endures, but also the frustration, fear, and hopelessness of confronting a deeply flawed and corrupt legal system that has failed to bring those responsible to justice. In 2017, reflecting on her life after the attack, Sreymom said: “Now I know what hell feels like.”

This report—based on Human Rights Watch research in Cambodia between December 2013 and May 2017, and on desk and telephone research through June 2018—describes 17 cases of intentional use of predominantly nitric or sulfuric acid in violent attacks. Perpetrators are mostly private actors seeking to inflict pain, permanently scar, or kill the victims. While the Cambodian government has passed legislation to curb the availability of acid used in such attacks and to provide accessible health care and legal support to victims, perpetrators rarely go to prison and victims rarely receive adequate health care or meaningful compensation. The government’s failure to enforce the law or provide remedies for victims exacerbates their plight, with consequences that last a lifetime.

* * *

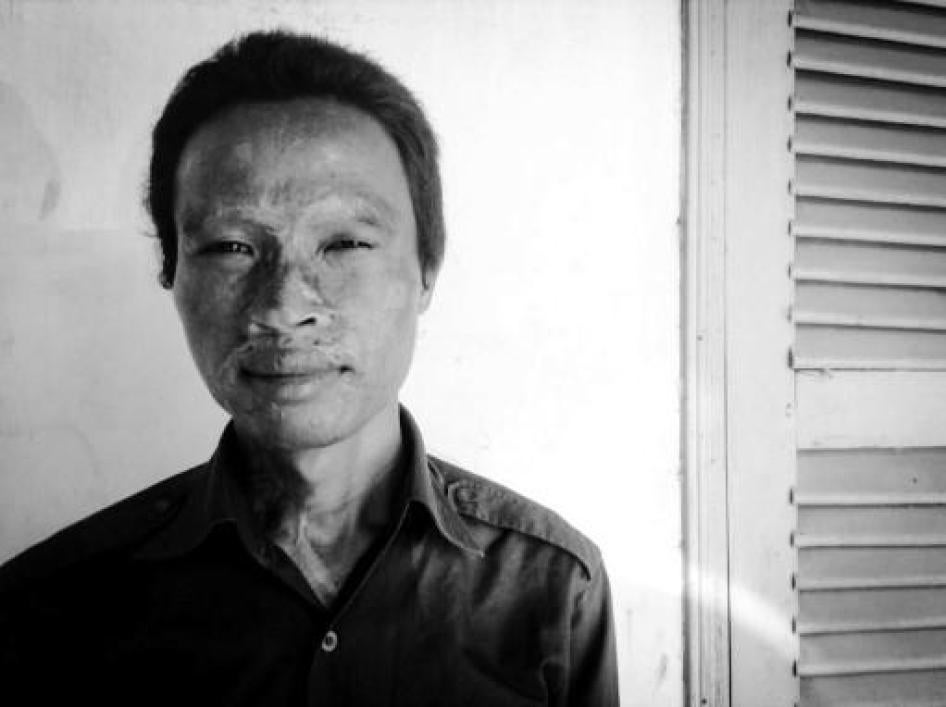

When concentrated acid is thrown on a person, it instantly melts through the skin and tissue, often down to the bone. Typically aimed at a person’s face, the acid quickly eats through eyes, ears, skin, and bone, dissolving flesh wherever it touches. Even if the acid is superficially washed off, it can continue to burn deeper into the skin and tissue for days. When Som Bunnarith’s wife threw acid on him in 2005, he thought that it was hot water, “but when I touched with my hands, I felt the skin melting from my face,” he explained. “For six months, I could smell the acid on my face when I would breathe in and out.”

In the immediate aftermath of an attack, victims have a variety of healthcare needs. At the outset, they are at high risk of infection—particularly in places like Cambodia where adequately sterile health facilities for burn victims are nearly nonexistent—and are in need of infection and air passage treatment, eye care, and pain management.

In 2012, Cambodia passed an Acid Law requiring state hospitals to provide medical care free of charge for acid attack survivors. In practice, however, the law appears to be routinely ignored. Every hospital staff person interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that the victim would need to pay, and none indicated any knowledge of this clause of the Acid Law. In May 2017, even the head doctor at the burn unit at Preah Kossamak Hospital—the largest public hospital in Cambodia and the only one with a dedicated burn unit—was unaware that acid victims have a right to be treated free of charge. Not a single acid attack victim Human Rights Watch interviewed had received treatment free of charge at a public hospital. Instead, survivors face the full range of problems anyone in need of emergency and other serious medical treatment faces in Cambodia, including denial of treatment until they show proof that they can pay or provide out-of-pocket payments.

Acid attack survivors often require numerous surgeries in the ensuing years. Burn wounds can take years to heal, and without adequate medical care can leave thick scars that cause lifelong physical harm by severely restricting basic movement. The nose and mouth can fuse shut, the chin can fuse with the neck or chest, and eyelids can become stuck open. Victims of severe attacks often require dozens of operations over many years to remove these scars so that the individual can regain mobility. Even with access to proper medical care—which most of the people we interviewed did not have—blindness, hearing loss, and other disabilities are common.

Acid violence is rarely directly fatal. Rather, victims live on in physical, emotional, economic, and social suffering. Victims are often left with severe and permanent disability, and may depend on family members for ongoing care, sometimes for the rest of their lives.

Some survivors of acid attacks we interviewed in Cambodia said that the psychological impact of the attack was the most significant. Many expressed having had suicidal thoughts, even years after the attack. Some said they suffered from debilitating post-traumatic stress. Groups that have worked extensively with survivors said that suicide, attempted suicide, and chronic depression are pervasive. The government has not provided any mental health services to survivors of acid violence.

Acid attack survivors have little likelihood of achieving justice in the courts. Victims of any crime in Cambodia typically cannot get meaningful attention from the police, prosecutors, or judges unless they have money to pay bribes or have influence. Should those responsible for the attack have positions of power, the chances of success are further reduced, and bringing a complaint could even be dangerous.

Corruption and negligence by the police also have a chilling effect on victims reporting cases. Women are dissuaded from reporting cases of domestic violence, for instance, out of fear that the police will do nothing, and that having reported the violence will put them in further danger. In some cases, such violence escalates and can include an attack with acid.

Because the general perception in Cambodian society is that acid attacks occur out of “love triangle” disputes, many people—including police officers and court officials—treat the victim, especially if a woman, as though they deserved the attack due to adultery or being the “mistress” of a married man. The severe scarring resulting from an attack serves as a permanent mark of their “guilt” that many survivors describe as making them feel further outcast from society.

Sun Sokney, who was attacked by her husband in a busy market in February 2016, said that people around her refused to help until she convinced them that she was the attacker’s wife, not a mistress. She added that until she convinced the crowd that she was his wife, they were cheering for him to run away to escape the police.

Perhaps the most infamous case of acid violence in Cambodia was the attack on 16-year-old Tat Marina in 1999. She had caught the eye of Svay Sitha, a 40-year-old deputy undersecretary of state in the Council of Ministers, who presented himself as a single businessman. Marina said that when Sitha’s wife, Khoun Sophal, learned of the relationship, she hired men to beat Marina unconscious and pour nitric acid on her face. No one was ever prosecuted for the attack on Marina—even though the assailants left behind identification—and she never received any compensation. Sitha currently serves as the undersecretary of state for the Office of the Council of Ministers.

Impunity prevailed not only in Marina’s case, but for most of the survivors interviewed for this report. Several spoke of facing pressure from government officials to accept an inadequate settlement out of court. Of the handful of cases that have made it to court, few have resulted in a conviction, and fewer still in the perpetrator serving out their sentence. At time of writing, not a single survivor interviewed for this report had received any compensation through the court system, despite provisions under the Cambodian Civil and Criminal Codes entitling victims of tortious act to remedy, including damages.

Key Recommendations

- Under the government of Prime Minister Hun Sen, in power since 1985, Cambodia’s healthcare and criminal justice systems have been beset by deep-rooted problems that prevent most Cambodians from obtaining adequate health care or having fair access to justice in the courts. These problems go well beyond the scope of this report. However, as detailed below, there are specific actions authorities can and should take to ensure that survivors of acid attacks get decent health care and a measure of justice. The government should:

- Revise the Criminal Code to make it a crime to obstruct the administration of justice, including by instructing or putting pressure on police, officials, judges, or prosecutors to act in a particular manner.

- Prohibit informal financial settlements in criminal cases, including those involving acid violence, that interfere with appropriate criminal prosecutions.

- Pass into law the long-promised draft victim and witness protection laws. Protection measures should include a program for the relocation of those at-risk, non-disclosure or limitations on the disclosure of information concerning the identity and whereabouts of witnesses, and evidentiary rules that permit witness testimony to be given in a manner that protects against harassment, intimidation, or coercion of the witness, while upholding the fair trial rights of the accused.

- Clarify the meaning of the provision of “legal support” under article 11 of the Acid Law as it relates to acid attack survivors. The government should act to ensure that this resource is provided and accessible to victims.

- Explicitly communicate to all public hospitals at all levels the legal requirement under article 11 of the Acid Law that all “state-owned hospitals or other state-owned health institutions shall provide support and treatment to the victim(s) of Concentrated Acid free of charge.” Make clear to state hospitals that they will be reimbursed by the government for the costs of this free treatment.

- Ensure that opioid pain medications such as morphine and codeine are both available in adequate quantities and practically available for those who need them, in accordance with Cambodia’s obligations under the right to health.

Methodology

This report is based on interviews conducted by Human Rights Watch in December 2013, June 2015, and May 2017 with 81 people, including 17 survivors of acid attacks in Phnom Penh and Kampong Cham, relatives of survivors, lawyers, experts from nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) working on acid violence, goldsmiths and motorcycle battery vendors in Phnom Penh, and battery vendors and rubber plantation workers in Kampong Cham and Tboung Khmum provinces.

Interviews were conducted in Khmer through an interpreter. Interviews with survivors were conducted in the privacy of the interviewee’s home and with only the interviewee, interpreter, and Human Rights Watch researcher present. In some cases, at the interviewee’s request, a family member or social worker from the Cambodia Acid Survivors Charity (CASC) was present.

All interviewees were advised of the purpose of the research and told that the information they shared would be used for inclusion in this report. It was made clear that Human Rights Watch could not provide any financial, legal, or medical assistance. Interviewees were informed of the voluntary nature of the interview, that they could refuse to answer any question, and that they could terminate the interview at any point.

Steps were taken to minimize re-traumatization: interviewees were given breaks throughout the interview when needed, and the researcher avoided questioning the interviewee about information already known from legal documents. Human Rights Watch also ensured that all interviewees had the ability to contact the researcher in case of any follow-up concerns.

In order to protect interviewees from possible retaliation, we have omitted names and identifying details or used pseudonyms in some instances. We have noted where pseudonyms have been used in relevant citations.

The exchange rate at time of research was on average 4,000 Cambodian riel to one US dollar. This rate has been used for conversions in the text, which have generally been rounded to the nearest dollar.

I. Background

Acid Attacks in Context

While acid attacks occur throughout the world, they are highly concentrated in South and Southeast Asia.[1] The problem varies from country to country in context, scope, and motivation. In India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Nepal, the vast majority of attacks are perpetrated against women.[2] The motivations cited for attacks in these countries include rejection of love, marriage, or sex; the victim having been raped and bringing shame to the family; domestic abuse; seeking education; and dowry disputes.[3]

In Bangladesh—the world leader in acid attacks with over 3,600 recorded cases in the last 18 years—the vast majority of cases involve men attacking women.[4] These include incidents stemming from land disputes in which a woman is attacked as a means of harming her husband or father by damaging their “property.”[5] In some parts of Afghanistan and Pakistan, girls describe acid attacks as a risk they take in daring to attend school.[6]

Cambodia reached a peak of 40 reported attacks in 2000, which is believed to have been due to “copycat” cases after the attack on Tat Marina.[7] There was another wave of attacks in 2010 with 36 reported victims.[8] Most arise out of interpersonal disputes and a desire for revenge.[9] Attacks are most frequent in the provinces of Kampong Cham (now Kampong Cham and Tboung Khmun provinces) and Phnom Penh. The prevalence of attacks in Kampong Cham is due to the availability of acid used for processing at the rubber plantations located there.[10]

Like Bangladesh and Pakistan, Cambodia passed a law specifically designed to address acid violence. The 2012 Acid Law broadly stipulates terms for regulating the production and distribution of concentrated acid, outlines legal procedures and punishments for perpetrators of acid attacks, and calls for the provision of medical, legal, and social services for acid attack survivors. Since the passage of the 2012 law, Cambodia has seen a reduction in attacks, though underreporting of incidents and lack of authoritative statistics make it impossible to know the full scope of the problem.[11] Until the enactment of the Acid Law, Cambodian law enforcement and medical personnel did not record incidents of acid violence as distinct from other forms of violent crime.

Since the passage of the law, there have been at least 25 reported acid attacks with 32 victims, 23 of whom are known to have survived; 19 of the victims were women and 13 were men.[12]

The proportion of male victims is higher in Cambodia than in Bangladesh or India, but female victims still make up the majority of cases, and there is a clear gendered dimension to many of the acid attacks in Cambodia. For example, many are preceded by gender-based offenses against the victim, such as domestic violence, that go unaddressed. Women who are subjected to domestic violence often do not feel comfortable reporting the incident to police because they fear both that the police will not take their case seriously and that the perpetrator will retaliate against them for having reported the crime.

Due to the perception that attacks were less frequent, funding for the Cambodian Acid Survivors Charity (CASC) was reduced, and it shut down entirely in 2014. But despite the decrease in the number of attacks, survivors still have ongoing needs. Allocation of NGO resources dedicated to the legal, psychosocial, economic, and medical support of acid survivors has decreased to almost nothing, leaving many survivors without much-needed assistance. The Cambodian government has failed to fill this gap, despite the legislative commitments to do so outlined in the 2012 Acid Law.

Legal Standards

The 2012 Acid Law and Sub-Decree

Cambodia’s legislature passed the Law on Regulating Concentrated Acid (the Acid Law) in December 2011, and it went into effect in January 2012.[13] The Sub-Decree N.48 on the Formalities and Conditions for Strong Acid Control (the Sub-Decree) was issued on January 31, 2013.[14] Though there are gaps in enforcement, the Acid Law and Sub-Decree marked a significant step forward in both preventing and sufficiently addressing the effects of acid violence in Cambodia.

The Acid Law defines concentrated acid and stipulates in broad terms how it is to be produced and distributed, as well as the legal procedures for prosecuting perpetrators of acid attacks. It requires the government to provide medical, legal, and rehabilitation support for acid burn survivors. The Sub-Decree elaborates on the articles of the Acid Law related to the availability, handling, and distribution of concentrated acid.

Criminalization

Those convicted of acid violence are subject to the punishments enumerated in the Acid Law. The duration of imprisonment and scope of the fine, dependent on the mental state of the perpetrator and the severity of the attack, are outlined below:

Article |

Crime |

Punishment |

|

16 |

“Intentional killing by using Concentrated Acid” with proof of an “advanced plan,” or if torture or cruel acts occurred “before or in the time of killing.”[15] |

Life imprisonment |

|

19 |

Torture or cruel acts leading to the unintentional death of the victim, or if the victim commits suicide as a result of the attack.[16] |

20-30 years in prison |

|

16 |

“Intentional killing by using Concentrated Acid” (without proof of an advanced plan or torture or cruel acts occurring before or in the time of the killing). |

15-30 years in prison |

|

19 |

Torture and cruel acts using concentrated acid leading to the loss of any body parts or other “permanent disability.” |

15-25 years in prison |

|

19 |

“Torture and cruel acts using Concentrated Acid on any other individual.” |

10-20 years in prison |

|

20 |

Intentional violence leading to the unintentional death of the victim. |

10-20 years in prison |

|

20 |

Intentional violence leading to the loss of a body part or other “permanent disability.” |

5-10 years in prison |

|

20 |

Intentional violence (a lesser offense than torture or cruel acts) using concentrated acid. |

2-5 years in prison and a fine of 4-10 million riel (US$1,000-$2,500) |

|

17 |

An attack that leads to the unintentional death of the victim.[17] |

1-5 years in prison and a fine of 2-10 million riel ($500-$2,500) |

|

21 |

Any act that leads to unintentional injury with concentrated acid. |

1-12 months in prison and a fine of 200,000-2 million riel ($50-$500) |

|

21 |

Any act with concentrated acid that leads to unintentional injury resulting in the loss of a body part or other “permanent disability.” |

6 months-3 years in prison and a fine of 1-6 million riel ($250-$1,500) |

Medical, Legal, and Rehabilitation Services

The Acid Law recognizes that many acid survivors will require immediate medical attention, legal support, and rehabilitation for which they are unable to pay. Article 11 of the Acid Law states that “health centers, state-owned hospitals, or other state-owned health institutions shall provide support and treatment to the victim(s) of Concentrated Acid free of charge,” and that “the state shall provide legal support to the victim(s) of Concentrated Acid.”[18] However, the law does not specify the form that this legal or medical support should take. Article 12 specifies that “support, rehabilitation, and reintegration of Concentrated Acid victims into society are [within the] competence of the Ministry of Social Affairs, Veterans, and Youth Rehabilitation.”[19]

Article 13 of the law appears to transfer some responsibility to civil society groups, stating, “The state encourages the participation from public, associations, national and international NGOs, and private sectors to support the victims of Concentrated Acid.”[20] Staff members from organizations said that, in practice, responsibility for ensuring such support to survivors had fallen entirely to the NGO community.

Leading up to and following the passage of the Acid Law, the Cambodian Acid Survivors Charity—the only organization in the country dedicated solely to survivors of acid attacks—played a central role in filling this gap. It maintained case records, provided legal support, helped to finance emergency and ongoing medical and psychosocial services, provided subsistence resources for survivors and their families, managed a safe shelter for survivors, and organized ongoing support group meetings with trained social workers.

Since CASC closed in 2014, however, the promise of the law has not been fulfilled to nearly the same extent: with CASC out of the picture, assistance has lapsed, leaving many survivors suddenly unable to obtain medical or psychosocial services, including regular support group meetings, and unable to afford to travel to court for trial proceedings.

Regulatory Framework

Chapter four of the Acid Law outlines the penalties for unauthorized production, distribution, and use or trading of acid, as well as penalties for perpetrators of attacks. Specifically, under article 14, any distribution or use of concentrated acid under 500 milliliters without a license is subject to a fine between 500,000 and 1.5 million riel (US$125-$375).[21] Distribution or use of amounts above 500 milliliters is subject to a fine between 1.5 and 10 million riel ($375-$2,500).[22]

The Sub-Decree further elaborates the regulatory regime which primarily falls under the responsibility of the Ministry of Interior and the Ministry of Industry, Mines, and Energy. The Sub-Decree requires that all distributors record “all information on purchase or sale” of acid in a register book that must be made available to police in any case of inspection; securely store and label acid with a clear danger warning; issue an invoice of sale to every purchaser; and maintain a certificate of origin for the acid and a material data safety sheet.[23] All purchasers must be at least 18 years old, present an “identification card and/or license authorization stating the professional occupation relevant to the usage of strong acid,” specify the purpose for the use of the strong acid, and maintain records of the invoice given by the seller or distributor.[24]

Domestic Violence Legislation

Another shortcoming in preventing acid violence has been poor police response to complaints about stalking, threats of impending attacks, and domestic violence, sometimes a precursor to acid attacks. In three of the cases Human Rights Watch documented, the perpetrators were partners or ex-partners with a history of domestic violence that had gone unchecked.

Sun Sokney, 24, told Human Rights Watch that after she married her husband, he repeatedly accused her of having affairs and beat her. One day, when the beatings were particularly bad, she asked for a divorce. He responded by kidnapping their 3-year-old daughter. A few days later, he followed her after work to a busy market and attacked her with concentrated acid. He absconded after the attack, but still calls her constantly, begging her to take him back. Sokney, who does not want to get back together with him, is terrified he will eventually attack her again. She does not want to pursue the case further—even to regain custody of her child—out of fear that the police will not take her seriously and that seeking help will only anger him more, potentially further endangering herself and her child.[25]

Cambodia passed a law criminalizing domestic violence in 2005, and has undertaken two National Action Plans to Prevent Violence Against Women (NAPVAW), both of which emphasize preventive measures.[26] The Domestic Violence Law itself, however, includes an ambiguous distinction between “minor” and more severe forms of domestic violence that interferes with timely prevention efforts. In cases of “minor misdemeanors” or “petty crimes,” the law recommends reconciliation or mediation, seemingly reserving prosecution for cases that have already resulted in serious injury.[27]

In 2017, the Cambodian League for the Promotion and Defense of Human Rights (LICADHO) released a report based on investigations of nearly 400 domestic violence cases between 2014 and 2016. It found that more than 40 percent of cases ended with the survivor remaining with her violent partner, and only 20 percent resulted in any criminal proceedings.[28] Reflecting the law’s stated goal to “preserve the harmony within the household in line with the nation’s good custom and tradition,” LICADHO found that when a woman approached the village or commune chief or the local police for help, the most common response was to discourage her from taking legal action.[29]

In 2015, the World Health Organization (WHO) found that only two in five women who experienced domestic violence in Cambodia sought assistance. When they do seek help, women often rely on informal mechanisms due to lack of resources and legal information, but also out of concerns about corruption. As in this report, WHO found that law enforcement officers, court clerks, judges, and prosecutors often require “fees” in order to pursue justice in any sort of criminal case.[30]

The Right to Health

The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), which Cambodia ratified in 1992, specifies that every person has a right “to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health.”[31] Because states have different levels of resources, international law does not mandate the kind of health care to be provided beyond a certain minimum level. The right to health is considered a right of “progressive realization,” meaning that by becoming party to the ICESCR, a state agrees “to take steps … to the maximum of its available resources” to achieve the full realization of the right to health.

However, the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR), the independent expert body charged with monitoring compliance with the ICESCR, maintains that there are certain core obligations that are so fundamental, all states must fulfill them regardless of financial status, observing that “a State party cannot, under any circumstances whatsoever, justify its non-compliance with the core obligations … which are non-derogable.”[32] In its General Comment No. 14 on the right to health, the CESCR has identified four essential elements of the right to health: availability, accessibility, acceptability, and quality, obligating states to make available in sufficient quantity “functioning public health and health-care facilities, goods and services, as well as programmes.”[33] As for accessibility, the committee defined four elements: accessibility without discrimination, physical accessibility, economic accessibility, and information accessibility. Acceptability refers to the need for health facilities, goods, and services to be respectful of medical ethics and culturally appropriate. Finally, they must be scientifically and medically appropriate, and of good quality.[34] The right to health also includes an obligation to “adopt and implement a national public health strategy and plan of action, on the basis of epidemiological evidence, addressing the health concerns of the whole population.”[35]

The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), which Cambodia ratified in 2012, states:

Persons with disabilities have the right to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health without discrimination on the basis of disability. States Parties shall take all appropriate measures to ensure access for persons with disabilities to health services that are gender-sensitive … including early identification and intervention as appropriate, and services designed to minimize and prevent further disabilities.[36]

Healthcare Needs of Acid Burn Survivors

Survivors of acid attacks have extensive healthcare needs. In the immediate aftermath of an attack, the most urgent needs are preserving the individual’s life and limiting damage to their health. This includes removal of the acid, infection control, respiratory support, and pain management. In the longer term, medical needs shift to healing damaged tissue, restoring the individual’s functionality, and critical mental health care. Victims of acid attacks frequently need medical attention at multiple levels of care. The summary of their care needs below draws on minimum standards of care for burn victims outlined in the Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF) clinical guidelines, WHO burn guidelines, and International Society for Burn Injuries (ISBI) treatment guidelines, as well as interviews with burn care experts.[37]

Limiting Damage

The first 10 minutes after an acid burn are critical for minimizing long-term damage. The first step should be the removal of the acid, followed by irrigation with clean, sterile water, and basic CPR to ensure that the airways are clear to prevent suffocation. A major concern within the first 48 hours of a burn is that the individual will go into shock for which IV fluid management is important.[38] Cambodia’s health centers—distributed for every 10 to 20 thousand people, according to a WHO health system review—which “in principle are available within two hours walk from home for the whole population,” should have the capacity to provide this first step in critical treatment, according to the Minimum Package of Activities set forth by the Ministry of Health.[39]

Infection Control

According to the MSF clinical guidelines on burn treatment, “precautions against infection are of paramount importance until healing is complete. Infection is one of the most frequent and serious complications of burns.”[40] In order to control for infection, MSF recommends rigorous adherence to the principles of asepsis and regular dressing changes and access to antibiotics.[41] The MSF guidelines recommend cefazolin IV, ciprofloxacin, and sulfadiazine, all of which are antibiotics on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines mandated by the WHO Action Programme on Essential Drugs, meaning equal access to these medications is considered a core, non-derogable obligation under the right to health.[42]

Pain Management

Pain is a major symptom for burn survivors and can cause immense psychological distress for burn patients.[43] According to the MSF clinical guidelines, pain management is a principle standard of burn care. Its treatment may require a variety of medical interventions including anesthesia or treatment with opioid analgesics. The MSF guidelines stipulate that “morphine is the treatment of choice for moderate to severe pain,” and provide recommended dosages of immediate and slow release morphine for continuous pain (at rest), during the rehabilitation process, and for acute pain during dressings and physiotherapy.[44]

Surgical Care

Restoring functionality is among the main priorities of medical care in the longer term for burn survivors. Without skin grafting early in the healing process, survivors’ bodies heal by tightening the skin around the wound. This may result in loss of mobility. For instance, if a survivor’s neck sustained damage as a result of an acid attack, the skin in the neck area may tighten in a way that the face is pulled toward the shoulder.[45] Regaining neck mobility in this case requires surgery to excise these scars and perform skin grafts. It is also important during the healing process to perform infection management, which is often a surgical procedure in the case of acid burns to remove toxic material and parts of a wound that may be developing infection.[46]

Consistent Psychosocial Care

One of the most enduring effects of an acid attack is the impact on a survivor’s mental health. Indeed, psychosocial care is considered a core element of burn care, and the International Society for Burn Injuries provides guidelines for psychosocial care at all stages of burn recovery.

Studies on burn recovery have found that the severity of depression is positively correlated with the intensity of the pain experienced by the survivor, and negatively correlated with the level of social support provided to the survivor.[47] While professional psychiatric or psychological care may not be available, it is critical that attention be given to the emotional needs of the survivor throughout the healing process.

In the immediate-term, when a patient is admitted into emergency care, they are likely to experience high anxiety and terror, and medical practitioners should focus on reassurance, normalization, and relaxation techniques. At the critical care phase, this anxiety may turn to acute stress disorder, and may require anti-anxiety medication, as well as continued psychological support. Finally, in the rehabilitation and reintegration phase, the survivor may experience post-traumatic stress disorder, and the ISBI recommends anti-depressant medication as needed, psychosocial community treatment programming, and psychotherapy.[48]

Availability of Concentrated Acid

Following the passage of the 2013 Sub-Decree, by mid-2015, when Human Rights Watch visited battery acid vendors in the three major markets in Phnom Penh, most said they had stopped selling concentrated acid.[49] One battery vendor told Human Rights Watch that the Ministry of Interior invited acid sellers to a meeting in 2013, which was attended by about 50 people. “The government does not allow me to sell strong acid,” she said.[50] Several vendors said that representatives from the Ministry of Interior had come in teams of three to four people to make sure that vendors were not selling concentrated acid and that they were keeping records of ID cards for those who procure diluted acid.[51]

In 2015, Human Rights Watch also visited acid vendors in Kampong Cham province, near the province’s rubber plantations. While a few vendors suggested that police had come to check their records to see if they were recording the IDs of those who purchased acid, Human Rights Watch and local colleagues were able to easily procure concentrated acid. Many acid vendors were aware of the potential harm of concentrated acid, so did not sell it for those reasons. However, with relaxed enforcement of the Sub-Decree in the provinces, particularly in Kampong Cham and Tboung Khmum where concentrated acid is used for the rubber industry and the highest number of attacks takes place, vendors with whom Human Rights Watch spoke were largely unaware of the Acid Law and Sub-Decree.

While the industries most commonly associated with concentrated acid are motorcycle battery shops and rubber plantations, goldsmiths also traditionally use it to polish and mold jewelry. In 2015, most goldsmiths with whom Human Rights Watch spoke had not heard of the Sub-Decree, and several goldsmiths in Phnom Penh were willing to sell concentrated acid for just US$1.50 per liter. When Human Rights Watch asked one of the goldsmiths who expressed a willingness to sell the concentrated acid whether anyone from the government had come to speak with him about the Acid Law, and whether they would need to see an ID to purchase the concentrated acid, he just laughed and shook his head “no.”[52]

When Human Rights Watch returned to the markets in 2017, enforcement of the concentrated acid regulations appeared strong within battery shops in Phnom Penh, but concentrated acid was still easily available from goldsmith tool supply shops on the periphery of the markets where goldsmiths work. None of the suppliers Human Rights Watch spoke with required an ID to purchase large volumes of concentrated acid ranging in price from 3,500 to 5,500 riel (about $0.85 to $1.35) per liter, and they all said that no government authorities had come to inform them of the Acid Law or Sub-Decree.

II. Barriers to Health Care for Survivors

Government Failure to Set and Implement Treatment Standards for Burn Victims

According to the World Health Organization, non-fatal burns are a leading cause of morbidity, including prolonged hospitalization, disfigurement, and disability, often with resulting stigma and rejection. In low- and middle-income countries, they are a leading cause of disability-adjusted life-years lost (that is, years lived with a disability that significantly impacts one’s daily functioning).[53] Cambodia is no exception.

Consistent with the right to health, the Cambodian government should set and implement a plan or policy to address burns and their health impacts. Cambodia’s 2012 Acid Law commits the government to providing free health care for survivors of acid burns. However, six years after the law’s adoption, the government has still not provided any guidance on what this commitment means in practice, including what kinds of services should be available or covered under the law.

Victims of acid attacks frequently need medical attention at multiple levels of care. A local health clinic is often their first point of contact with the healthcare system due to their proximity to where people live. While these facilities may be able to provide some initial emergency care, such as removing acid from the victim’s body, they are generally not adequately equipped to provide the emergency care that is needed. They are unlikely to have oxygen, antibiotics, or adequate pain medications, or be able to respond to potential complications. Ministry of Health guidelines suggest that secondary care referral hospitals should be able to provide essential burn care. According to these guidelines, such hospitals offer both outpatient and inpatient care, have the capacity to perform basic surgical interventions and certain laboratory tests, and can provide rehabilitation services.[54] However, in the absence of any kind of government guidelines on burn care, it is not clear what medications and other supplies for treatment of burn victims are actually available at this level of care. Several burn survivors told Human Rights Watch that secondary care hospitals said that they were not equipped to treat them, and sent them on to specialist hospitals in Phnom Penh, causing further delays in the treatment of urgent medical problems.

Cambodia has one specialized burn unit at the public Preah Kossamak Hospital in Phnom Penh, established in August 2016, with 10 dedicated medical practitioners, including two specialists. The unit has the capacity to perform skin grafts and other procedures critical for severe burn treatment. The nonprofit Children’s Surgical Centre also has staff trained in treatment of burns, although it is an NGO-funded hospital. Reflecting the general gap in care between rural and urban health systems in the country, the fact that the only public hospital equipped to provide care for acid burn victims is located in Phnom Penh significantly complicates access to these services for those living outside the capital.[55] Kampong Cham province, which has the highest rate of attacks, is approximately 127 kilometers from Phnom Penh—at least three hours by car.

Interviews with victims of acid attacks suggest that inadequate knowledge and medical supplies as well as the lack of standards and guidance from the government at lower levels of the healthcare system lead to denied or delayed care, which may result in permanent loss of health.

The cases of Kong Touch, 55, and Som Bunnarith, 48, illustrate the challenges people outside of Phnom Penh face in accessing medical care. On September 15, 2011, Kong Touch was walking to work at a rubber plantation in the early morning when she heard someone following her. As she turned around, Pov Kolap threw five liters of concentrated acid in her face, creating third-degree burns on her face, neck, chest, arms, breast, and abdomen.[56] Kong Touch was turned away from her local clinic as they were not equipped to treat her burns. She then went to the Kampong Cham provincial hospital, where staff called the Cambodian Acid Survivors Charity for help, since they also did not have the resources or expertise to sufficiently treat her wounds. CASC then transferred Kong Touch to the Children’s Surgical Centre in Phnom Penh, where she received seven surgical treatments on her eyes, mouth, head, arms, and chest, including several skin grafts. She lost her right eye.[57]

Early in the morning on December 31, 2005, Som Bunnarith’s wife, Ear Kimly, went looking for her husband since he had not returned home for several nights. When he did, she threw a bottle of battery acid in his face. Bunnarith was first brought to a local hospital in Pursat province. Staff there referred him to a hospital in Battambang province, where he remained for seven days. There, staff cleaned his wounds and put saline solution in his eyes. With the saline he could momentarily see clearly, but he was not immediately seen by an eye specialist. Maintaining that his eyesight was undamaged, his private health insurance company did not authorize payment for any further ophthalmological care and, according to Bunnarith, the hospital ceased treating his eyes, even though he told medical staff that his vision was deteriorating. Bunnarith then went to a private eye clinic in Phnom Penh, where he said the medical professionals confirmed to him that his eyes “could have been cured, but because [he] did not get the right initial treatment that it was too late.”[58]

Inadequate Pain Management

Pain is a major symptom for burn survivors—particularly in the short term and through the healing process—and can be a major cause of psychological distress.[59] Beyond this, chronic and severe pain can impair a survivor’s ability to seek gainful employment or even engage in everyday activities.

Our interviews suggest that pain is rarely managed appropriately in Cambodia. This is a problem that not only affects burn survivors, but also Cambodians with other health conditions that cause pain. In a February 2018 joint workshop, Douleurs Sans Frontieres (“Pain Without Borders”) and Cambodia’s Ministry of Health reported that 80 percent of Cambodians with life-threatening illnesses suffer unnecessarily from severe pain.[60]

This gap in basic healthcare provision for people with life-threatening illnesses is largely due to the low availability of opioid analgesics and severe restrictions on their prescribing in the country. The average quantity of opioid analgesics Cambodia used between 2011 and 2013 was sufficient to treat just 10 percent of the country’s late stage cancer and AIDS patients over that period for moderate to severe pain.[61] A 2011 Human Rights Watch study found that Cambodia had by far the most restrictive regulations on opioid analgesics of the 11 Asian countries surveyed. Cambodia’s regulations require doctors to get a special license to prescribe morphine; require multiple doctors to sign off on such prescriptions; and impose a seven-day limit on the period a prescription can cover.[62]

In the seven years since this study, access has barely improved, and the same severe restrictions remain. The most problematic restriction is the strict seven-day limit for morphine prescriptions. This time limit, combined with the fact that the medicine is only scarcely available in Phnom Penh, creates significant obstacles to its accessibility in rural areas. At time of writing, no public hospitals outside of the capital carried oral morphine.[63] For the rural poor, the out-of-pocket expenses alongside required costly travel to Phnom Penh means access to pain relief can be cost-prohibitive, particularly when the trip must be repeated every seven days. Even in Phnom Penh, morphine remains scarce; oral morphine is only available at the Khmer Soviet Friendship Hospital (KSFH) and Calmette Hospital, both public. Preah Kossamak Hospital, the only public hospital with a dedicated burn unit, does not carry oral morphine. KSFH and Calmette Hospital were out of stock of oral morphine for about nine months between October 2017 and July 2018.

The MSF clinical guidelines for burn care recommend morphine for moderate to severe burn pain as well as for continuous pain during recovery and for acute pain during dressings and physiotherapy.[64] As morphine and codeine are on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines, countries need to provide these medications as part of their core obligations under the right to health.[65] Moreover, Cambodia is obligated to make sure that they are both available in adequate quantities and physically and financially accessible for people who need them, including those living outside of the capital, especially for vulnerable or marginalized groups.[66] The Cambodian government is five years into its National Strategic Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases 2013-2020, which includes increasing access to palliative care as one of its four priority objectives.[67] Actions to achieve these objectives outlined by the Ministry of Health include improving “drug availability for palliative medicines and opioid analgesics.”[68] However, there is currently no funding for palliative care in the national health budget, and there has been no change in regulations of opioid analgesics since 2008.[69]

Inadequate Mental and Psychosocial Healthcare Services

Many of the survivors with whom Human Rights Watch spoke expressed having suicidal thoughts, even years after the attack. “I don’t want to live,” Moung Sreymom said. “I want to die. I only live for my daughter because I love her so much.”[70] For some, the post-traumatic stress months or even years later can feel debilitating.

Adequate provision of mental and psychosocial healthcare services is generally lacking in Cambodia; such services were essentially unavailable until after the 1993 elections.[71] As of 2015, there were only 49 trained psychiatrists in Cambodia, only 10 of whom were working outside of Phnom Penh, and 45 psychiatric nurses for a population of over 15 million.[72] Access to much-needed psychosocial services for survivors of acid attacks is no better: there is currently no government-provided psychosocial care for survivors.

Som Bunnarith attempted suicide multiple times after he was attacked. “One night, when I was staying at my sister’s home in my hometown Dong Khao, I waited until night and then snuck outside with a krama [Khmer scarf] to find the tree to hang myself,” he said. Completely blind, Bunnarith spent the entire night wandering outside searching for a tree and was unable to find his way back to the house. “When my sister found me, she cried because she thought that I was trying to commit suicide. I didn’t want to make her worry so I lied.… But if I had found the tree, I would have hanged myself.” Two days later, his son found him trying to hang himself with a krama on a metal bar.[73]

Nearly all the survivors with whom Human Rights Watch spoke described feelings of constant high-anxiety, nightmares, and fear of walking alone at night. Many survivors had come to depend on CASC’s regular support group meetings, which brought together survivors from all over the country. CASC also provided access to social workers and, where possible, mental health counseling. With the closure of CASC, these meetings no longer take place, and survivors endure the psychological stress without access to much-needed mental health services.

Out-of-Pocket Payments and Refusal of Treatment

Cambodia does not have a universal health insurance system; out-of-pocket payments are common and pose a significant burden on the poor. A 2015 WHO report reviewing Cambodia’s health system found that “the predominance of out-of-pocket health expenditure remains a major barrier to accessing health care, especially for the poor and vulnerable, and puts people at risk of impoverishment.”[74] Although the Acid Law stipulates that public health institutions shall provide “support and treatment to the victim(s) of Concentrated Acid free of charge,” every hospital staff person interviewed by Human Rights Watch said that the victim would need to pay, and did not indicate any knowledge of this clause of the Acid Law. Indeed, in 2017, even the head doctor at the burn unit at Preah Kossamak Hospital—the largest public hospital in Cambodia and the only one with a dedicated burn unit—was unaware that acid victims have a right to be treated free of charge.[75] Not a single acid attack victim Human Rights Watch interviewed had received treatment free of charge at a public hospital.

On January 1, 2017, six months after Sa Sokha, 18, and Kea Samnang, 22, were engaged, Samnang’s ex-girlfriend poured acid over Sokha’s head, also hitting Samnang. Samnang’s uncle rushed them to the nearest clinic, which turned out to be private, on his motorbike. Samnang’s family paid an initial US$100 for first aid at the clinic, but could not afford further treatment so they traveled to Preah Kossamak Hospital in Phnom Penh.

The couple spent almost two months at Preah Kossamak Hospital. Samnang had four surgeries and Sokha had one. “There was no free treatment,” Samnang said. “Every time they took blood, gave medications, anything, they took money.”[76] Sokha explained that she and her husband had to take out a high-interest loan from a relative to cover the medical expenses. Sokha, who had worked as a traditional Apsara dancer, said she lost her job after the attack because, in her words, “I am not beautiful anymore.”[77] She now works as a cashier in an outdoor market in Phnom Penh and can no longer afford to go to school. “I lost everything,” she told Human Rights Watch, “my time, my work, my dancing, and school.”[78]

In several cases, survivors said that hospitals refused to initiate treatment, including emergency interventions, until they could prove they could pay for urgent care. Delays in treatment after such attacks are likely to prolong the healing process and can be fatal.

For instance, the public hospital that Sun Sokney was rushed to after she was attacked with acid demanded payment before providing treatment. Sokney said that on their second wedding anniversary, her husband followed her to a busy market after she got off work at a garment factory and doused her with acid. After someone in the market called an ambulance, she was taken to the nearest public hospital. In what appears to be a common practice in Cambodia, Sokney said that before she was transferred from the ambulance to the hospital, the driver made her brother-in-law pay $70.[79] When she got to the emergency room at Phnom Penh’s public Calmette Hospital, she said that the doctors asked if anyone in her family could afford to pay, but her immediate family had not yet arrived at the hospital. The doctor gave her an IV and dressed her wounds, but left her without pain medication or any further treatment for 14 hours. Not until a representative from her factory union came to the hospital to prove that the union would cover her medical expenses did Sokney receive morphine and further treatment.[80]

On March 15, 2017, Sorn Chanty, 24, was biking home from beauty school in Phnom Penh at about 8 p.m. when suddenly a man ran at her, grabbed her bag off her handlebars, and threw acid in her face. Someone nearby immediately called an ambulance. Chanty said that when the ambulance arrived about an hour later, the ambulance crew told her to go inside but refused to drive or perform first aid procedures. “I waited inside for 15 minutes. I was screaming for them to go to the hospital but they wouldn't leave, I didn't understand,” she said. “When my ex-boyfriend arrived, they finally took me to Preah Kossamak.” Chanty said that once they reached the hospital, the driver refused to let her out of the vehicle until her ex-boyfriend paid the driver $30. Once at the hospital, they had to pay another $25 to be allowed inside the emergency room, which her ex-boyfriend again paid. She was brought to the burn unit where they cleaned and dressed her wounds. She spent $60 to stay at the hospital for two nights before a representative from her garment factory labor union came and took over payment for the remainder of her treatment at Preah Kossamak Hospital.[81]

Thouen Sam Orn, 24, was working as a cook at a roadside food stall in Phnom Penh. One morning in April 2014, she was preparing rice as usual before opening when a woman came by and asked for some rice. When she gave it to her, the woman suddenly threw acid in her face, dousing her upper body as well. As the acid burned through her clothes, she ripped them off and stood screaming naked in the street. She called her husband who took her to the nearest private clinic. Unable to afford the cost, Sam Orn was sent to the public Preah Kossamak Hospital. She received treatment for three days but was then forced to leave—despite needing further medical care—because she and her family could not afford to pay the $50 per day the hospital charged. “We couldn’t afford it, so my younger brother asked the doctor for permission for me to leave the hospital because of the money,” Sam Orn said. “The doctor said okay, and I was forced to leave because I had no money.”[82]

As the cases above suggest, the Cambodian government has not ensured that public hospitals are aware of or have the resources and expertise necessary to fulfill their legal responsibilities to acid attack victims, including provision of free medical services. Every acid attack survivor living outside of Phnom Penh with whom Human Rights Watch spoke said they had to seek funding from NGOs, family, or friends to get treatment in the capital. As NGO support has disappeared, moreover, survivors have been increasingly forced to go without treatment altogether or take loans from family members, if any have the funds, to pay for medical expenses. This financial burden contributes significantly to the pressure on survivors to agree to inadequate out-of-court financial settlements and forego justice.

III. Barriers to Justice

Acid attack survivors described being threatened by police and court officials to drop their cases or settle out of court, being pressed to pay bribes in exchange for justice, and, at times, facing reluctance or outright refusal by the police to pursue their cases. These problems are common to all Cambodian victims of serious criminal offenses who seek justice through the criminal justice system. As Moung Sreymom told Human Rights Watch: “In this country, there is no justice unless you have money.”[83]

There is corruption at all levels of government in Cambodia, and the courts are not competent, impartial, or independent. As a result, victims without money or political clout are unlikely to get a fair day in court or receive adequate compensation from the perpetrator. These problems are exacerbated when the alleged perpetrator has money or clout or is linked to someone who does.

Deeply entrenched impunity and corruption in the judiciary and police force have not abated over the years. The UN, donor countries, and domestic and international NGOs have long called for reforms to improve the administration of justice and curtail corruption, but without significant effect.

Article 11 of the Acid Law states that “the state shall provide legal support to the victim(s) of Concentrated Acid.” However, neither the law nor the Sub-Decree expanding on the law specifies the form that this legal support should take. None of the acid attack survivors with whom Human Rights Watch spoke said they were provided legal support from the Cambodian Ministry of Justice or any other government entity. Rather, survivors, including five of those who filed cases under the Acid Law, described being pressured by court officials to drop their case and settle out of court or pay large bribes in exchange for justice.[84] Dr. Honng Lairapo, who served as both the medical and legal manager at the Cambodian Acid Survivors Charity before it closed, medically treating and representing numerous acid survivors in court, told Human Rights Watch that he has received many threats from families of perpetrators and court officials to drop cases.[85]

When Chantou filed a case in a local court after she was attacked in 2009, the court did not order the arrest of her attacker even though Chantou clearly identified her. Rather, the judge encouraged the families involved to settle out of court. Chantou refused and continued to pursue the case, which eventually reached the appeals court in Phnom Penh. The local court clerk then allegedly threatened Chantou, warning her to stop pursuing the case and accept the out-of-court settlement on offer. Chantou ultimately took the money out of fear, which continues to haunt her: “I still feel terrified of the attacker who lives very close by,” she said. “I am worried that maybe she will one day come to take revenge.”[86]

After she was attacked with acid in January 2017, Pheng Sreyla, 24, was summoned to court. She said the judge offered her US$4,000 to withdraw her case, apparently from the assailant. The judge assured her that her attackers would remain in prison, but a week later she saw the woman who attacked her in their village. When Sreyla called the judge and asked why her attacker was walking free, he said, “It’s not trial time yet.” She said that when she asked when there would be a trial, the judge responded, “When you ask like this, that’s why we always have problems.”[87] After what felt like a hostile interaction, she stopped asking about her case. Sreyla told Human Rights Watch: “It felt like the judge was pressuring me take the $4,000 and I needed it for treatment. I had already borrowed $2,600 from others and was paying interest.”[88] So she took the settlement, not entirely aware of what this meant for her ability to continue pursuing justice.

When Kea Samnang and Sa Sokha filed a case against Pet Sreyrath, they were summoned to the court for negotiation in April 2017. They were never assigned a public prosecutor. When Samnang arrived at the courthouse, he said he was brought into a meeting with two men, one of whom he believes was the judge. Samnang said that the man whom he believed was a judge asked him if he would withdraw the case for $3,000. But Samnang’s family had paid more than that to cover medical expenses. “I said no, but the judge kept asking me over and over,” Samnang said.[89]

Before a survivor can pursue a case in court, there must be a police investigation. Most of the survivors Human Rights Watch spoke with expressed little faith in the police, and some said that police corruption was a direct obstacle to pursuing justice. Because of the uncertainty about whether police will follow through with an investigation or arrest, some survivors chose not to report an attack out of fear of retribution.

When Sorn Chanty was attacked on her way home from beauty school in March 2017, she believed her ex-boyfriend was behind the attack. She had recently ended the relationship after learning he had another girlfriend, but “he kept trying to pressure me to stay with him,” she said. When she filed the police report, she told the officers that she believed it was him:

The police tried to investigate by asking him over and over, but they just pressured him to pay them money, not to be arrested. My family pressured me to withdraw the complaint about him, so I did. I felt scared of him before the attack and I still do now. He comes often. I feel scared. He visits as a friend, but he is coming to try to make a relationship. My family is pressuring me to marry this boy, but I am worried about the future.[90]

After Thouen Sam Orn was attacked in April 2014, she immediately filed a police report, but said that the police seemed uninterested in pursuing the case and never called for any more information. “I tried calling twice per week after the attack to try to push them to investigate the case, but they just kept saying they’re working on it. I am not confident in the police work,” Sam Orn said.[91] She has lost all hope of pursuing her case.

The ineffectiveness of the Cambodian justice system is felt hardest by those who do not have the resources to make the system work for them. Even basic information can be difficult to access. For instance, after a victim files a case, it can be difficult to find out the status of the case from the authorities. Human Rights Watch met with several acid attack survivors who simply wanted to know the status of their case and whether their attacker was in prison.

There is no centralized public repository of court verdicts in Cambodia, making it difficult to learn the judgment in a case, even one’s own. Often this just serves to hide the police’s failure to investigate a case or bring a prosecution, particularly if the criminal suspect has wealth or power. Even when there are convictions, appeals can take years. There is only one appeals court for the entire country, inundated with hundreds of cases every year, and individuals who are convicted can repeatedly appeal the verdict or their sentencing.

In June 2012, Kong Touch became the first person to file a case under the Acid Law. The Kampong Cham municipal court found her attacker, Pov Kolap, guilty of “intentional violence using acid leading to mutilation or permanent disability” under article 21 of the law, and sentenced him to 10 years in prison and the payment of $5,000 compensation to Touch. In July 2012, Kolap appealed the decision. In March 2013, the appeals court upheld the verdict. In July 2015, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of a prosecution appeal that Pov Kolap instead be convicted of attempted murder, but maintained the 10-year sentence.[92]

Throughout this process, Kong Touch did not receive government-provided legal support, despite the case being filed under the Acid Law. CASC paid for her lawyer’s fees, transportation to and from court, and any other requirements for pursuing the case.[93]

On February 5, 2008, Chiev Chenda was riding on a motorbike together with her three children when a group of five men threw concentrated acid in her face. Her then 3 year old, Malita, was sitting in front of her and suffered severe acid burns to her head, face, neck, and arms.[94] As the acid burned through her clothes, scorching her skin and leaving her naked in the middle of the street, Chenda saw her attacker grinning as he watched her try to cover herself. “I'll never forget his face,” she said. “He stood there and laughed.”[95] This is the last image she ever saw.

Chiev Chenda went to court four times for hearings. She described her experience in court to Human Rights Watch:

Nobody helped me in the court. Nobody came to talk to me. Nobody cared about me. I only wish that the court would ask me these questions the way that you are now. Nobody at the court talked to me. I only want the lawyer to ask me questions like this so I would feel better. They all talked about me, but not to me. I feel hopeless about my case.[96]

Chenda was not given any accommodation for her blindness or psychosocial support during the trial. She has been all but shut out of her case because without legal aid, she is dependent on her estranged husband, who acts without consulting her.[97] She said that even her private lawyer, selected by her husband, never consulted with her. She would like to be involved but has found it impossible to directly access the legal process:

My husband says that I am a useless person and why should I be thinking about this case? I call him over and over again to ask about the procedure of my case, and he always says he is busy and hangs up. I don’t know who my lawyer is—everything depends on my husband.[98]

Chenda knows four people were arrested in her case and convicted; three were sentenced to 14 years in prison and one to 10 years.[99] She told Human Rights Watch that she is unsure whether the four are actually serving their sentences.

As noted, it is unclear what the provision of “legal support” in the Acid Law means. In the cases Human Rights Watch examined, none of the survivors were provided free public legal representation.

Victim and Witness Protection

Nearly every survivor who spoke with Human Rights Watch said they were reluctant to pursue legal redress out of fear of retaliation. Many interviewees who had filed formal criminal or civil complaints said they had lived in fear since doing so. One reason for these concerns is the absence of a government protection program for victims and witnesses in cases of violent crime, including acid attacks.

One night in 1997, Deb Da, 10 years old at the time, was asleep in bed with his mother and younger brother when there was a knock at the door of their home. His mother opened the door and two men immediately held her to the ground, while their neighbor forced her to drink hydrochloric acid. When Deb Da started crying and screaming, “The woman turned toward me and splashed me in the face with the acid to make me stop.”[100] Deb Da said his mother was dead within 15 minutes. The young Deb Da did not yet understand what was going on: “I just knew that it was hot. It was extremely hot, and at the beginning I could not see clearly, and I thought that I would be blind and I heard adults yelling, ‘It’s acid!’”[101]

Deb Da’s aunt brought him and his younger brother to the local hospital, but they were not sure how to treat him, so they sent him to Kampong Cham, where he was then transferred to Kantha Bopha Children’s Hospital in Phnom Penh. He spent four months there. At one point, he asked a doctor to kill him by injecting air through his IV. “I was scared of myself,” he said. “I was scared of my own body.”[102]

That year, Deb Da’s uncle filed a criminal case with the help of the human rights group LICADHO for the murder of Deb Da’s mother and the acid attacks. Deb Da appeared as a civil party in the trial. “When I first lodged the complaint … I was afraid that they would come and kill me because I was the only one who saw them very clearly,” he said. Deb Da moved from house to house for two years to hide, and ultimately was given shelter by World Vision for four years.[103]

Deb Da said that two of the attackers—the neighbor and one of her accomplices—were convicted of murder and sentenced. One of the accomplices was still at large. The accomplice, who testified he had been paid $5 to assist in the crime, was sentenced to three years and served out his sentence. The neighbor was sentenced to 18 years, but she was released from prison after 11 years. Deb Da does not know why:

It makes me feel very sad and depressed. This woman killed my mother and now she lives a normal life. I am not satisfied with this justice system in Cambodia. She lives happily one kilometer from my home. I do not want revenge by hurting or killing her, but I want justice from the law.[104]

Deb Da would like to appeal, but he is hesitant: “If I try to follow the case, I think that woman may do something bad to me, or my wife, or my child.”[105]

Fear also impels some acid attack survivors to extend their stays in medical facilities after an attack. Chantou, who requested we change all identifying details about her case out of fear of retaliation, was attacked with diluted acid as she lay sleeping with her two children one night in September 2009. She said she stayed at CASC for four months because she was afraid to return home.[106] Survivors may not be entirely safe at the hospital either. Dr. Lairapo said that sometimes attackers or relatives of an attacker go to the hospital saying they are relatives of the patient, only to attack the patient or threaten them not to file a case.[107]

Chan Buntheon, 45, who was attacked in Kampong Speu in September 1997 by the wife of a man she had been seeing, said that after she was released from the hospital, the attacker’s children would come to visit her. She was convinced that they were visiting out of remorse. But one day the two sons tried to strangle her with a TV cable, she told Human Rights Watch. Buntheon did not file a complaint because she was afraid of further attacks if she did. “I was very afraid after that event,” she said. “My siblings kept me in different places, so sometimes I would stay with one sister, sometimes with another.”[108]

Kong Touch described the enduring fear she has felt since she was attacked: “After the incident … even if someone walked passed me I was so scared.”[109] Touch believes that others were involved in the attack, but she did not push for their prosecution. “I felt dead inside,” she said. “But I still think the police should have investigated the case on their own.” Asked if she was concerned about revenge for publicly pursuing her case, she responded: “I am terrified of revenge. I feel frightened of the perpetrator taking revenge on me or my children, but I am still hoping for justice.”[110]

Such fears will remain common among survivors of acid attacks so long as legal protection of witnesses remains weak under Cambodian law. The Criminal Procedure Code provides for provisional detention of alleged perpetrators of crimes in order to “prevent any harassment of witnesses or victims or prevent any collusion between the charged person and accomplices,” but there is so far no witness protection program.[111] Cambodia did join five other Southeast Asian countries in Kuta, Indonesia, in November 2013 to discuss witness protection matters, and joined in affirming:

The necessity of revising and adopting national measures and mechanisms for the effective protection of witnesses from potential retaliation or intimidation for witnesses in criminal proceedings, and the protection and assistance of victims of crime.… Also the necessity to adopt measures to establish physical protection of witnesses, such as relocation of witnesses, non-disclosure or limitations on the disclosure of information concerning the identity and whereabouts of witnesses, and provide evidentiary rules to permit witness testimony to be given in a manner that ensures the safety of the witnesses.[112]

At a regional meeting in the Philippines, the Cambodian government committed to drafting a witness protection law “as soon as possible.”[113] In November 2014, Om Yentieng, the head of Cambodia’s Anti-Corruption Unit, announced plans to draft legislation to protect whistleblowers and to assemble a committee to draft broader witness protection measures in accordance with the UN Convention against Corruption, to which Cambodia acceded in 2007.[114] Though the finalizing of the laws has been repeatedly postponed, Yentieng announced at a journalist workshop in December 2017 that the drafting of the Law on Witness and Reporting Person Protection was almost complete.[115] At time of writing, nearly four years since work on them began, the draft laws have still not been made public.

Compensation

Cambodian law does not provide state funds for survivors of acid attacks, and none of the individuals interviewed by Human Rights Watch received any court-ordered compensation. In some cases, survivors were pressured or threatened, including by government officials, not to pursue legal recourse at all or to settle out of court. Some cases were protracted for years, often due to the accused absconding. In some cases where there was a decision, the person convicted simply has not paid.

Acid attack victims in particular are often in need of compensation immediately following the attack because of medical expenses. Additionally, the attack often causes physical disabilities that may make it impossible to perform the work that the survivor had previously relied on for income. Thong Kham was doused with acid on May 5, 1990, while standing next to an intended target. Nearly 25 years later, on November 4, 2015, she passed away without ever having received any compensation. In 2005, Thong Kham had told the CASC:

I had to stay home for a long time trying to hide myself from society. I wasn’t able to work anymore, as I feared people would not accept me. My family lived a difficult life because of me as I wasn’t able to provide them their needs.[116]

Despite going through the entire legal process, 23 years after the attack, Deb Da said, “I have never seen one cent of compensation [from the accused] for my case.”[117]

Moung Sreymom, who has also not received any compensation, previously owned a stall in the marketplace. Since the attack, she mostly spends her days recovering. In the last year, she has begun working in her neighborhood giving manicures, while her husband drives a motorcycle taxi donated by the Swiss organization Smiling Gecko.[118] The assailants allegedly fled to Vietnam, and Sreymom’s case has been stalled for over three years. She said:

To be honest, my whole body is in terrible pain, but my heart is in just as much pain.… I do not want to take any revenge, I only want justice and the money to cover my treatment.[119]

Chiev Chenda, who supports herself and two daughters by working at the Cambodian Children’s Fund packing rice for $3.50 per day, said: “I know the perpetrator was arrested, but I did not get any compensation.”[120]

Only two survivors of acid attacks who spoke to Human Rights Watch said they had received any financial compensation from the perpetrators. Chantou and Pheng Sreyla said they had agreed to minimal compensation under duress—that is, they both said that they were pressured by court officials to drop their case and accept an informal settlement. Out of fear and the dire need for expensive medical care, both women accepted the minimal informal compensation.

There are a number of factors common to all cases of personal injury in Cambodia that encourage victims to accept relatively small settlements in exchange for dropping their criminal complaints. Reasons include the common misconception that convicted defendants found to owe victims compensation need only pay after they have served their prison time, at which point the victim must file another petition to the court to request the compensation be paid out.[121] This is not true.

Both Cambodia’s Civil and Criminal Procedure Codes provide for the payment of damages for tortious acts such as wrongful death, bodily harm, and mental or emotional distress caused by bodily injury or injury to honor or reputation.[122] A criminal court may order compensation only after the accused has been convicted of the offense, including all possible appeals.[123] And while this means that it can be many years before a survivor is legally entitled to compensation, it is not true that the victim must wait until after the perpetrator has served their sentence or file an additional petition in order to receive compensation.

In some cases, though, despite being convicted and ordered to pay remedies, the convicted person still does not pay. In this case, they can be imprisoned for up to two years.[124] In order to request imprisonment for failure to pay, the victim must first provide evidence that they have exhausted “all means of enforcement provided in the law such as seizing personal or real property.”[125] However, there is no clear legal pathway to pursue seizure of property, and most survivors lack essential information about their rights, legal options, and how the compensation process works. If someone is imprisoned, they are not relieved from their obligation to pay, though they cannot be imprisoned again for failure to pay.[126] At this juncture, there is no legal recourse for the survivor to pursue a remedy, making the likelihood that a survivor ever sees compensation extremely low. These factors, along with a defendant who is able to influence police, prosecutors, and judges, can make enforcement of damages difficult, if not impossible, leaving survivors extremely vulnerable to pressure to accept manifestly inadequate out-of-court settlements or risk ending up obtaining no compensation at all.

This weak legal framework for pursuing compensation makes the Cambodian government’s commitments in the Acid Law to providing legal support and free medical care to acid attack survivors even more critical.

Access to Justice for People with Disabilities

Human Rights Watch spoke to several lawyers representing acid attack victims who said they were unaware of any accommodations to ensure that their clients with physical disabilities could participate in the trial.[127]

Kong Touch, who has been struggling to adjust to 50 percent eyesight, said she felt discriminated against because of her physical appearance and because the justice system did nothing to assist her with travel to the court:

The court was not helpful at all with my blindness. Sometimes, the people at the court would discriminate. I cannot see it, but I felt that they might have the feeling of discrimination. I noticed that they do not want to talk with me.[128]

Former CASC employees noted that clients often relied on them to provide necessary support throughout the trials. In particular, survivors need help in physically getting to the court given that the disabilities resulting from the attack, such as blindness or restricted mobility, make it especially difficult to travel from Kampong Cham to Phnom Penh. The closure of CASC makes the lack of accessible court facilities a significant obstacle to survivors’ access to legal redress.

Acid attack survivors in Cambodia also face cultural stigma that exacerbates the discrimination they face as people with disabilities. Cultural stigma is sometimes exacerbated by beliefs of karma in Buddhist culture. Some survivors describe being ostracized because their appearance is believed to be a result of karma—that they must have done something terrible in their past that they are paying for now. Some survivors also believe this about themselves.[129]

The government is responsible for ensuring that people with disabilities have access to justice on an equal basis with others, and that the court system does not discriminate against people with disabilities. Cambodia is a party to the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which obligates states parties to “recognize that all persons are equal before and under the law,” and to “ensure effective access to justice for persons with disabilities on an equal basis with others.”[130]