The idea that domestic violence is not a serious criminal offense is hard to grasp. How did this happen?

Russia doesn’t have a national domestic violence law. Some acts of domestic violence can be prosecuted under the criminal code as assault, but domestic violence isn’t seen as any different than assault on the street by a stranger. It’s actually taken less seriously than public assault because at least when it’s public, the police is much more likely to intervene.

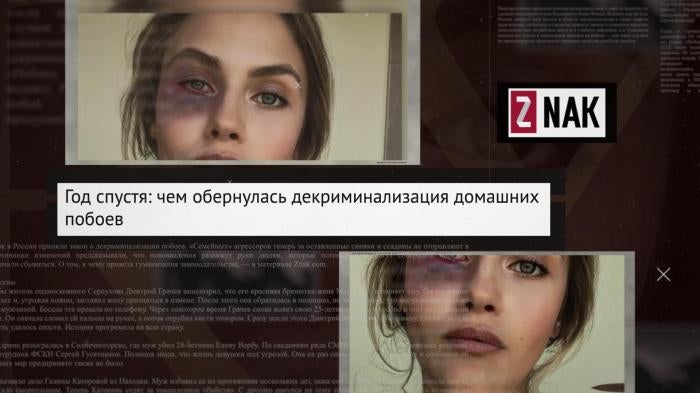

The worrying step the government took in February 2017 was to make what protection exists under the criminal code even narrower and weaker. They decriminalized first offenses of what’s called “family battery.” This was a very serious setback for people living with domestic violence.

What does that mean?

Basically, if it is the first time someone is accused of battering a family member or if they haven’t been accused of it for a year, it’s now treated as an administrative offense – no different from a parking violation. Penalties are a lot milder than for a criminal offense, and most often they get away with a slap on the wrist, like a small fine.

This was like giving a green light to domestic violence. To many, it seemed like the government was officially saying “it is fine to beat up your wife.”

Was there an increase in violence?

Because domestic violence isn’t a stand-alone offense, there aren’t any comprehensive statistics. Research says that 70 to 90 percent of women suffering domestic violence in Russia don’t report it, and that women are three times more likely to be assaulted by a family member than a stranger.

Women’s rights groups and experts have said they have seen more people coming forward and reporting domestic violence since the law changed. The increase could be because of greater levels of abuse, but it could also be because the amendment caused a lot of public debate, giving women the confidence to come forward.

We are also seeing increasingly brutal cases being made public, like murders or a woman whose partner cut off her hands. Really horrendous violence. We know that family violence escalates if nothing is done. But with the decriminalization, it is even more difficult for survivors to get help from authorities when the abuse starts.

You mentioned domestic violence is more widely talked about now. What change is that bringing about?

There was a lot of controversy when family battery was decriminalized. Some senior officials spoke out publicly against it, which is very unusual. Russian women’s rights groups have been campaigning to make domestic violence a separate offense for years. From 2012 until 2014, lawyers and experts drafted a law on preventing family violence. Russia’s lower parliament, the State Duma, never did anything with the draft. It just sat there.

Now we’re hoping it will be reintroduced and adopted this time.

Can you talk about some of the women you spoke to and what they had been through?

I spoke to women in horrifying situations. They had been brutally beaten, sometimes with wooden sticks or metal rods, burned on purpose, had their teeth knocked out, been thrown out of windows, or locked outside in subzero temperatures. Some women were raped by their husbands. A number of women said the abuse began when they became pregnant and escalated after that.

Some women told me they didn’t know they had options, because they had never seen or experienced any other way to live.

There was one woman whose husband was abusing her, and she got access to the help she needed in the most roundabout way because she didn’t know these services existed. Her gynecologist told her she was stressed, so she went to a psychologist. She told the psychologist that she “wants to be a better wife” so she would “stop provoking” her husband. The psychologist eventually referred her to a crisis center that provides specialized support to domestic violence survivors. It all took months and the whole time, she continued to face severe physical and psychological abuse at home. And even this is unusual, since often people will simply blame the woman for bringing the violence on herself instead of referring her for help.

Someone else whose husband beat her repeatedly once had to lock herself in a room with her three children so he couldn’t get to them. This has had a huge psychological and physical impact on her and her children. She was so distressed talking to me, she was trying not to cry and she was shaking. I suggested ending the interview, so as not to retraumatize her.

Then she shocked me by saying she had to end the interview because her husband was expecting her home – they were still together. Then she said she was “owning [up] to [her] mistakes and working very hard not to provoke him.”

How widespread is domestic violence in the country?

It’s difficult to say for sure, but studies suggest every fifth woman in Russia has experienced domestic violence. Like everywhere in the world, in Russia it can affect anyone and is hugely underreported. What I found was that women who were better educated or had higher income were the most reluctant to speak out because there is still a lot of shame around it. People think it should be handled behind closed doors because it is a “family matter”. There is also a lot of victim blaming, even from people who are supposed to be offering services to help.

Are there shelters?

There are some, but nowhere near as many as there needs to be, and the government-run ones are incredibly difficult to get into. They demand all sorts of documentation, local [residence permit], medical certificates, x-rays, sometimes documents confirming the woman’s income. Even then, we found cases in which they made women wait weeks for a decision. Women who go to shelters are in desperate and dangerous situations, sometimes life-threatening. They can’t wait for an hour, let alone days or weeks.

A few nongovernmental organizations also provide shelters, which are often overfilled even though the government ones are frequently nowhere near capacity because they are so hard to get into. These NGOs do incredible work in a hostile environment. Many of them have been branded – or are constantly facing a threat of being branded – a “foreign agent,” which is the equivalent of being called a spy under Russian laws that clamp down on civil society. They have been struggling to stay afloat.

If a woman does report abuse, what happens?

We heard many reports of police being dismissive and sometimes mocking or blaming the woman. Even social workers sometimes push them to reconcile with their husbands and “do better.” Police more often than not refuse to register or investigate complaints of domestic violence and sexual assault, often arguing that the women are guilty or complicit in their own abuse. Others will say things like, “You’re just going to go back to him anyway, so why should I bother?”

If a woman does want to take her abuser to court, what are her options?

Very few people I spoke to were able to do this, because the system really works against them. Most domestic violence cases are prosecuted through so-called private prosecution, an incredibly unfair process. The survivor must gather the evidence and bear all costs and hire a lawyer to take the case to court. It’s completely overwhelming.

There was one woman – she and her husband were both successful professionals. Her husband assaulted her 23 times over 10 years – when they were married, including while she was suing him for domestic violence, and after they were divorced. After almost every hearing, he attacked her. Four times he attacked her right outside the courthouse and no one could do anything because there’s no such thing as a protection order.

Can anything be done?

Absolutely. There are very clear steps that need to happen. Russia needs to adopt a law on domestic violence, making it a stand-alone offense to be investigated and prosecuted by the state. There should be protection orders. Police should be trained to respond effectively to domestic violence reports. The state should ensure that women facing domestic violence have effective access to support services, including emergency shelters.

Domestic violence survivors in Russia are basically left on their own. The state does not protect them, and it doesn’t help them on the scale that is needed. That needs to change.