Summary

He pushed me, I fell on the floor and he kicked me in the stomach. He said it was his dream to meet a pure girl, and that I was a disappointment, not pure. He started keeping me up every night, forcing me to “tell him the truth” about men I’ve been with before I met him. . . I started believing that I was no good, lost a lot of weight, my self-esteem was gone... He started beating me more frequently, once he dunked my head in the toilet. When holidays came, he locked the apartment door and said calmly, ‘I will beat the truth out of you now.’ By that point, I started wearing a thick bathrobe in the house so that it hurt less when he hit me. He stuck a knife under my fingernails, hit me over the head with a wooden stool, beat me with a belt. Then he held my head up and urinated on my face. My son cried, “Mama, please, just tell him the truth.”

—Liza, a 33-year-old kindergarten teacher from Pskov

Liza’s partner continued to beat, torment and humiliate her and her five-year old son for a year. After she mustered the courage and resources and left him, he started stalking her. Liza called the police several times, but they refused to take her statement, saying that it was “family business.” One day the man attacked her outside her new apartment building, grabbed her purse, and took her apartment keys:

I called the police again and told them that I can’t get away from him [and] asked them to help. I waited outside my apartment building for the police to arrive. He was still holding my purse. He [smirked at me and] said: “They will not do anything to me.” He was right. The police arrived, and the policeman said to me, “What’s the problem? He seems like a totally normal young man. If you’re bothered about the key, just change the locks.”

Liza’s and other women’s stories described in this report illustrate how Russia’s law enforcement, judicial and social systems do not protect or support women who face even severe physical violence and other abuse at the hands of their partners. This report describes the significant gaps in Russian legislation that deprive women of protection from, and justice for, domestic violence, including dramatic, recent steps backward that put survivors at heightened risk. It details the barriers survivors face in reporting and getting help, including social stigma, lack of awareness about domestic violence and services for survivors, and lack of trust in police.

The report documents how police often treat victims of domestic violence with open hostility and refuse to register or investigate their complaints of domestic violence, instead funneling victims who wish to prosecute into the patently unfair and extremely burdensome process of private prosecution, for which the victim must gather all necessary evidence and bear all costs. In the cases we documented, survivors of domestic violence found the process of private prosecution overwhelming and ineffective, and for this reason decided to forego it altogether.

The report also shows how state services fail to ensure crucial support for survivors of domestic violence, demanding from them a laundry list of documentation to obtain emergency shelter, making them await a decision for weeks, and then in some cases denying them access to shelter, all while they face the ongoing risk of abuse.

Survivors of domestic violence, lawyers, women’s rights groups, governmental and nongovernmental service providers, and public officials interviewed for this report described vicious abuse of women by husbands and partners. The violence typically escalated over time, in some cases lasting years, and had a severe and lasting impact on the survivors’ physical and psychological health. Human Rights Watch interviewed women who described being choked, punched, beaten with wooden sticks and metal rods, burned intentionally, threatened with various weapons, sexually assaulted and raped, pushed from balconies and windows, having their teeth knocked out, and being subjected to severe psychological abuse. In cases where women had children, the violence typically began or escalated while they were pregnant, and their children were also exposed to the violence.

In Russia, like elsewhere, domestic violence affects people regardless of class, age, ethnicity, or other attributes. It can involve physical, sexual, economic, and emotional abuse, often repeated over time, and in the most severe cases may result in death. In Russia, domestic violence is perpetrated by different family members, and women make up the overwhelming majority of survivors.

Russian law does not take into account key aspects of domestic violence that aggravate the seriousness of the offense and render it more pernicious than an isolated assault. For example, it does not take into account that often the victim is economically dependent on the perpetrator, they often live together, and the abuse is usually repetitive and continues over a lengthy period of time.

Despite public awareness campaigns and two decades of discussion, as well as sustained efforts by women’s rights organizations and activists, Russia does not have a national domestic violence law, and domestic violence is not a standalone offense in either the criminal or administrative code.

The lack of a standalone offense reinforces an impression, held by many, that Russian authorities do not see domestic violence as a significant crime which has public rather than simply private ramifications. It also makes it difficult for Russian government agencies to maintain consistent, comprehensive statistics. This impedes both a full understanding of the scope of domestic violence and the development of effective strategies to combat and prevent it.

Russian law also does not provide for protection orders, which could help keep women safe from recurrent violence by their partners.

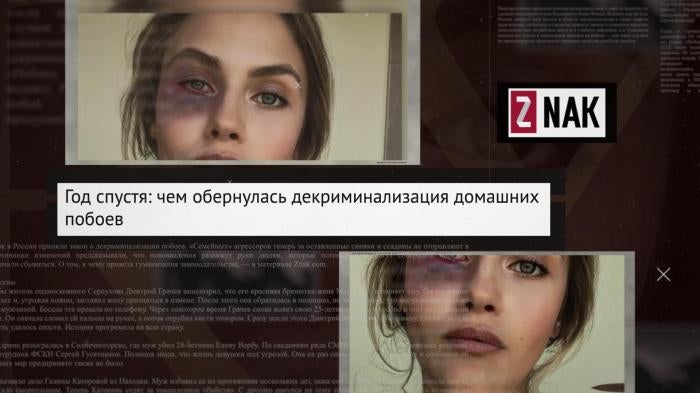

Legislative amendments adopted in February 2017 decriminalized first battery offenses among family, marking a further, serious setback. Such offenses are now treated in the same manner as first battery offenses committed by non-family members, which in 2016 became an administrative offense with very mild penalties. The 2017 amendments symbolized a green light for domestic violence by reducing penalties for perpetrators, made it harder for women to seek prosecution of their abusers, and weakened protections for victims.

While official statistics on domestic violence in Russia are fragmented, several indicators suggest it is pervasive. Official studies suggest that at least every fifth woman in Russia has experienced physical violence at the hands of their husband or partner at some point during their lives. A widely cited independent study revealed that women in Russia are three times more likely to be subjected to violence by a family member than a stranger. According to experts’ estimates, between 60 and 70 percent of women who suffer family violence do not report it or seek help and only around 3 percent of domestic violence cases make it to court.

Most women we interviewed did not report numerous instances of severe domestic violence to police. We found that a range of factors contribute to this: social stigma attached to the issue, which public officials, including law enforcement and judges often reinforce; overwhelming lack of awareness about domestic violence among survivors themselves, their immediate family and friends, and also in some cases by social services, on which they relied; lack of trust in police and poor police response; victims’ fear of retaliation by abusive partners; financial dependence on husbands or partners and fear of losing custody of their children.

Domestic violence in Russia is still, more frequently than not, approached in the context of child abuse and child welfare rather than as a standalone issue. It is also still predominantly viewed as a private, “family” matter. Police, courts, and sometimes even service providers engage in victim-blaming and advise women seeking protection to reconcile with their abusers or avoid “provoking” them. For example, a lawyer representing a survivor of domestic violence told Human Rights Watch that when her client called police after her husband attacked her with a knife and attempted to choke her, the police berated her, saying, “Why did you make it worse by provoking him? He was drunk, you should have just let him sleep it off.”

In many cases, Russia’s social service infrastructure does not adequately provide for the needs of survivors of domestic violence. State resources for survivors are limited and well below levels recommended by the Council of Europe, of which Russia is a member. Spaces in shelters that specialize in protecting women from domestic violence are few. Some of the state-run shelters require survivors to apply for entry, which includes a daunting amount of paperwork that can be difficult, if not impossible, for a survivor to amass. At times, state shelters may take weeks to issue a decision about granting shelter space to survivors of domestic violence– many of whom are already in a state of crisis, face severe threats of further violence, and have nowhere else to turn. Shelters tend to be located in urban centers, meaning that women in rural and remote areas have even less access.

Nongovernmental (NGO) crisis centers and shelters play a crucial role in providing services, often in life-threatening situations, that may not be available at a state-run facility. In many cases we documented, survivors of domestic violence who needed and found places at NGO-run shelters had previously been turned away by government-run shelters. However, NGOs struggle to provide shelters on the scale that is needed because of financial constraints and government restrictions on obtaining foreign funding. They also operate in a poisonous political atmosphere in which authorities brand independent groups as “foreign agents” to sow public mistrust of them.

Lawmakers who pushed for the 2017 decriminalization amendments equated efforts to prevent and punish domestic violence as interference in the Russian family and an assault on “traditional values.” This reflects the conservative trend that has dominated Russian politics in recent years and that has revitalized and “normalized” misconceptions and stereotypes about domestic violence, such as the perverse view that women themselves have “caused,” “provoked,” or “deserved” violence, and that women should tolerate abuse for the sake of their children.

Russian public perceptions of gender-based violence are starting to change, in large part due to the awareness-raising efforts of nongovernmental groups and coalitions, such as the Consortium of Women’s Nongovernmental Associations, the ANNA Center for the Prevention of Violence, Nasiliu.net, and others. Several members of parliament supported a draft law on domestic violence that would address many of the key legal gaps. Some government officials, for example in the Ministry of Labor and Social Protection, and also the Ombudsperson, seem aware of the shortcomings in the state’s response to domestic violence. They support measures to prevent domestic violence and ensure legal and other protection for survivors, including adoption of a standalone law. Several top officials have publicly acknowledged that the amendments decriminalizing first battery offenses have led to higher levels of violence.

The Russian parliament should adopt a law that treats domestic violence as a standalone criminal offense to be investigated and prosecuted by the state, rather than through the process of private prosecution. It should also adopt legal provisions creating protection orders. Russian authorities should ensure that police respond effectively to reports of domestic violence and that women facing domestic violence have effective access to support services, with support including, if needed, temporary shelter through simplified procedures.

If the Russian government does not act to change the situation, it will continue to put lives at risk and leave survivors of domestic violence to face abuse on their own.

Recommendations

To the Parliament of the Russian Federation

- Adopt a separate law on domestic violence that:

- defines, prohibits and criminalizes violence in the family;

- stipulates accountability for perpetrators;

- introduces mandatory training for state officials;

- provides for better access to services for survivors through establishment and financial support of shelters and crisis centers;

- Amend the Criminal Code to:

- ensure that it addresses domestic violence as a separate criminal offense, either by introducing it as a standalone offense or listing domestic violence as an aggravated circumstance in existing provisions for crimes against the person, with harsher penalties for perpetrators;

- repeal the legislative amendments of February 2017 and reinstate criminal liability for first offense of battery within family;

- introduce sanctions for negligence by law enforcement officials while responding to domestic violence complaints (article 293 of the Criminal Code) if such negligence led to minor, moderate, or severe harm to health or to someone’s death;

- Amend the Criminal Procedure Code to:

- transfer all domestic violence offenses to the sphere of private-public or public prosecution;

- provide for protection orders whereby a presumed victim of domestic violence can get immediate protection from perpetrators of domestic violence who are ordered not to contact or be within a certain distance of the victim;

- Ratify the CoE Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence Against Women and Domestic Violence (Istanbul Convention).

To the Government of the Russian Federation:

- Raise public awareness by regularly conducting nationwide information campaigns that explain the specific nature of domestic violence; comprehensively explain the rights of victims, the responsibilities of law enforcement, magistrate judges, and other authorities; and contain detailed information on available services for survivors and how to access them, including shelters and crisis centers;

- Condemn at the highest political level all forms of gender-based violence, including domestic violence; demonstrate political will to take steps towards combating domestic violence;

- Instruct relevant law enforcement agencies, such as the Ministry of Interior, the prosecutor general’s office, and the investigative committee to gather data about domestic violence crimes; and make the gathering of such data compulsory;

- Improve and streamline the process of compiling statistics on domestic violence, disaggregated by age, region, type of violence, and relationship between the victim and the perpetrator; undertake efforts to compile regular, relevant, and up-to-date research on the extent, causes, and effects of domestic violence; ensure that all data is transparent and publicly available;

- Improve and foster coordination among relevant government agencies, to ensure a streamlined approach to dealing with domestic violence;

- Introduce mandatory, specialized, and continuing education and training on domestic violence for social workers, health workers, psychologists, lawyers and other relevant professions;

- Introduce mandatory, comprehensive, and up-to-date training on domestic violence for police officers, prosecutors, judges and other relevant public officials;

- Ensure adequate funding for the Ministry of Labor and Social Protection and other relevant government ministries, on national and regional levels, to support programs aimed at combating and preventing domestic violence and assisting survivors of domestic violence;

- In collaboration with relevant ministries and nongovernmental agencies, develop and implement a national strategy to prevent and combat domestic violence;

- Ensure that independent nongovernmental groups that work on domestic violence can operate freely and without undue interference, including by prompt repeal of the 2012 “foreign agents” law and the 2015 “undesirables” law;

- Seek a follow-up visit by the United Nations (UN) special rapporteur on violence against women.

To the Ministry of Interior

- Improve the collection of consolidated statistical data on the overall number of domestic violence cases, with the breakdown showing the number of criminal and administrative proceedings initiated, the relationship between the victim and the perpetrator, the number of cases dropped, the number of complaints where no proceedings were initiated, and the number of instances in which police referred to a woman seeking to file a domestic violence complaint to a magistrate judge;

- Design and implement mandatory and ongoing/continuing training for police officers on how to respond to domestic violence complaints; ensure that the training adheres to international best-practice standards on survivor-centered response, including by refraining from victim-blaming and mocking, and prioritizing the wellbeing and protection of the victim;

- Engage with intergovernmental agencies and national and international nongovernmental organizations and agencies for technical support in training of police;

- Introduce and enforce disciplinary sanctions for police officers who fail to register or investigate domestic violence complaints or respond appropriately to victims attempting to register complaints, including by engaging in victim-blaming, mocking, or other hostile interactions with people who attempt to file domestic violence complaints;

To the Prosecutor’s Office

- Review and ensure compliance of law enforcement officials with Russian law and international human rights standards regarding investigation and prosecution of domestic violence offenses;

- Ensure effective oversight over investigations of cases of domestic violence by law enforcement;

- Train prosecutors to more rigorously oversee investigations of complaints of domestic violence and to more effectively prosecute cases of domestic violence;

To the Ministry of Labor and Social Protection

- Ensure that survivors of domestic violence, including in rural areas, have access to adequate services and support, including shelter, health, psychosocial, and legal services, through:

- In accordance with CoE standards, which recommend a minimum of one shelter space per 10,000 people where shelters are the predominant or only form of service provision, ensuring that at minimum 14,400 spaces in specialized shelters are available for victims of domestic violence; to meet this goal, establish more state shelters and ensure that NGOs have the resources to establish and run shelters, and can operate in an environment free of the kind of hostility described in this report;

- Ensuring that specialized shelters for survivors of domestic violence are located within reasonable distance and accessible to survivors of domestic violence in both urban and rural areas;

- Lowering thresholds for acceptance and referral to services in order to ensure that services, including shelters, are immediately accessible to all those who suffered from domestic violence, irrespective of their age, place of residence, disability, migration/residency status, including survivors with or without dependent children;

- Eliminating the requirement for a local residency registration to access shelters;

- Ensure regular funding for local nongovernmental groups working to provide services to survivors of domestic violence.

To the Ministry of Justice

- Provide regular trainings for judges on their response to domestic violence cases;

- Perform periodic reviews of domestic battery cases that have been adjudicated by magistrate judges to assess whether the cases were inappropriately relegated to private prosecution;

- Once legislation has been introduced to provide for orders of protection, conduct mandatory training of judges on applying them.

To International Organizations and Russia’s International Partners

- In line with the CoE standards to protect women’s rights and prevent gender-based violence, the CoE should press for more assistance and redress for victims of such violence, and provide support to civil society and governmental initiatives to monitor and combat domestic violence;

- The UN special rapporteur on violence against women, its causes, and consequences should request access for a follow-up visit to Russia;

- Russia’s international partners and international agencies, including UN Women, should raise concerns about domestic violence in Russia and urge the government to implement the above-mentioned recommendations.

Methodology

This report is based on Human Rights Watch field research conducted between November 2017 and May 2018 in Moscow and the Moscow region, St. Petersburg, Pskov, Vladivostok, Nizhny Novgorod, and Archangelsk. Additional meetings, as well as phone and Skype interviews, were conducted during the same period.

Human Rights Watch selected the cities based on consultations with Russian women’s groups and service providers, in order to give an overview of the situation with support for survivors of domestic violence in different parts of Russia. The scope of this project does not include Russia’s Northern Caucasus republics, where previous research by Human Rights Watch and other groups indicates that some local government policies, religious and traditional bias, and social arrangements make women particularly vulnerable to domestic violence, including “honor” killings. In several the Northern Caucasus regions, the situation is exacerbated by the fact that in the event of separation or divorce, typically the father and his family raise the children, in accordance with local custom, leaving the mother with very limited access to her children.

While conducting research for this report, Human Rights Watch also requested information from and visits to governmental service providers in several other cities, including Krasnodar, Tyumen, and Ekaterinburg. Several organizations did not respond, and two declined to provide information or meet with Human Rights Watch researchers.

This report is based on 69 in-depth interviews. Human Rights Watch researchers conducted most interviews in person in the above-listed cities, and some by telephone and Skype. Twenty-seven of the women interviewed, ages 22 to 45, were survivors of domestic violence. Interviews lasted from one to two-and-a-half hours. Almost all of the women interviewed were abused by their current/former partners or current/former spouses; one was abused by her brother. They came from both urban and rural areas from all over the country, including central Russia, western Russia, the Far East region, and the Ural Mountains region, and other parts of Siberia. Their education levels ranged from high school to post-graduate degrees. Four of these interviews were conducted jointly by two Human Rights Watch researchers, one male and one female, five by a male researcher, and 18 by a female researcher.

All interviews were conducted in Russian by Russian-speaking researchers. Human Rights Watch informed all of the women of the purpose of the interview, its voluntary nature, and the goal and public nature of our reports, and told them that they could end the interview at any time. All women gave their oral consent to participate in the interview. No interviewee received compensation for providing information; one interviewee who met with Human Rights Watch was reimbursed for her travel expenses. Where possible, Human Rights Watch provided women with contact information for organizations offering legal, social, or counseling services. Pseudonyms have been used for most of the individuals interviewed. In some cases, we have withheld the locations of interviews, as well as additional identifying details, in the interests of the interviewees’ safety.

Human Rights Watch also interviewed 19 practicing lawyers and women’s rights advocates, 13 representatives of Russian governmental and nongovernmental service providers, as well as government officials, academics, police officers, and representatives of non-Russian NGOs. Additional information was gathered from published sources, including laws, government data, academic research, and media.

Human Rights Watch met with officials from Russia’s Ministry of Labor and Social Protection. In February 2018, Human Rights Watch sent letters requesting meetings and information to the Interior Ministry, the Health Ministry, and the Justice Ministry, as well as to the Office of the Prosecutor General; at time of writing, we have not received responses.

This report focuses on domestic violence as a form of violence against women. While domestic violence affects men, women, and children, in Russia, women are the most frequent victims of such abuse.

I. Background

The Scope of the Problem: Limited Data

At time of writing, there are 78.8 million women in Russia, and they comprise 54 percent of Russia’s population.[1]

A study published in 2012, carried out by Russia’s Federal Statistics Service and the Health Ministry, suggested that at least every fifth woman in Russia has experienced physical violence at the hands of their husband or partner at some point during their lives. This is the most recent, comprehensive representative study based on research in 60 Russian regions (federal subjects).[2]

According to a 2008 assessment by the Interior Ministry, the most recent such assessment available, up to 40 percent of all grave violent crimes in Russia are committed within the family, and every fourth family in Russia experiences violence.[3] Among women respondents to a 2016 opinion poll, 12 percent said they experienced battery by their present or former husband or partner (2 percent, often; 4 percent, several times; 6 percent, once or twice).[4] A widely-cited independent study , published in 2007, revealed that women in Russia are three times more likely to be subjected to violence in the family than from strangers.[5]

Though some Russian state bodies do keep some data on violence within the family, the government does not systematically collect information on domestic abuse, and official statistics are scarce, fragmented, and unclear. The lack of a law on domestic violence or legal definition of domestic violence prevents categorization of the abuses as such, thus contributing to the absence of specific statistics.

Statistical data published by RosStat, Russia’s Federal Statistics Service, with direct reference to the Interior Ministry, shows a steady increase in the number of violent offenses committed against family members in Russia up until 2017. In 2012, it was 32,845, with 24,017 committed against women. Of the 32,845, almost 13,000 were violent crimes committed against a spouse (of which 11,534, or 90 percent, targeted wives).[6] In 2016, the number of violent offenses within the family rose to 64,421, with 29,465 committed against a spouse (of which 27,090, or 92 percent, targeted wives). In 2017, the number of crimes committed against family members dropped to 34,007. [7] (The drop is attributed to the 2017 decriminalization amendments, described below).

The true numbers of victims are likely much higher than the above data indicates, due to several factors. First, the above-cited numbers cover only those instances in which criminal proceedings were initiated: they do not reflect the actual numbers of complaints to the police or instances where police refused to initiate criminal investigation or instructed women to file a complaint with a magistrate judge for a private prosecution.

Second, domestic violence is underreported worldwide, including in Russia.[8] Official studies suggest that only around 10 percent of survivors of domestic violence in Russia report incidents of violence to the police.[9] According to experts’ estimates, between 60 and 70 percent of women who suffer family violence do not report it or seek help.[10] Moreover, experts, rights groups, and service providers interviewed for this report told Human Rights Watch that Russian police rarely open criminal cases on domestic violence complaints and, even when they do, most criminal cases are dropped before they can lead to a conviction.[11]

Several government agencies, including the Ministry of Labor and Social Protection, the Ministry of Interior, the Ministry of Justice, the prosecutor’s office, and the Investigative Committee, are involved in responding to domestic violence, but there is no coordinated response or national governmental program or strategy.

Some officials have voiced support for the government to do more to tackle domestic violence. For example, a senior Ministry of Labor official said that they supported the initiative to adopt a law on domestic violence. The official recognized that a coordinated, unified approach among relevant state bodies was important:

A point of view, shared by many in [another] ministry, for example, is that there should not be a focus on prevention of domestic violence. We [the Ministry of Labor and Social Protection], on the other hand, think that prevention is as important as social protection and rehabilitation of victims.[12]

Russia’s human rights ombudsperson, Tatiana Moskalkova, publicly expressed support for a domestic violence law and state financing for crisis centers.[13] She also said that Russia should swiftly ratify the Council of Europe Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence against Women and Domestic Violence (Istanbul Convention).[14]

Public Debate: “Traditional Values” v. Shifting Public Opinion

In recent years, with more public debate in Russia about domestic violence, public perceptions are still mixed but starting to shift from viewing gender-based violence as permissible or “normal,” to recognizing it as a prevalent problem and a serious concern that must be addressed. For example, 77 percent of respondents in a 2016 Russia-wide survey acknowledged that assault and battery occurring between spouses during an argument are unacceptable.[15] In a similar survey from August 2018, almost 55 percent of respondents said domestic violence should be a criminal offense in Russia.[16]

The 2017 adoption of legislative amendments decriminalizing first instances of domestic violence sparked public controversy and for a while brought the issue of domestic violence to the forefront of public debate. Several television channels aired programs with domestic violence experts who criticized the amendments, and women’s rights activists and rights groups organized social media campaigns and rallies in major Russian cities against the new legislation.

At the same time, some opinion polls suggested that a significant number of people in Russia still viewed domestic violence as a private matter between couples. For example, in a January 2017 opinion poll, 19 percent of respondents said that under certain circumstances hitting a wife, husband, or child is permissible; 59 percent of respondents said they either fully or partially supported the initiative to make domestic violence an administrative, instead of a criminal, offense; and 40 percent of respondents said that changing the law would have no effect on occurrences of domestic violence.[17]

Some lawmakers as well as officials in the executive branch of the government have publicly supported reforms to protect women from domestic violence. However, the politicization of “traditional values” in Russia, together with a strong anti-foreigner stance in political rhetoric and in law has made it much more difficult to do so.

A conservative trend has dominated Russian politics in recent years, reflected in, among other things, the growing role of the Russian Orthodox Church in politics and its influence on Russian society. Some politicians equated efforts to prevent and punish domestic violence as an assault on “traditional values” and on the Russian family. This trend has revitalized stereotypes of male power and authority over women that are deeply rooted in Russia.[18]

Public officials’ embrace of this rhetoric helps to shape social norms and hostile attitudes that foster domestic violence, stigmatize survivors, and discourage them from seeking help or recourse to justice. Such rhetoric can lead to “normalization” of violence within the family and may contribute to a sense that women should be expected to tolerate repeated incidents of domestic violence. For instance, 75 percent of women who called Russia’s National Hotline for Violence Prevention in 2017 had experienced regular violence before calling the hotline, with frequency ranging between once a week and once a month.[19]

The anti-foreigner trend has had a direct impact on the ability of NGOs and coalitions to provide legal, social, and other support to survivors of domestic violence. A 2012 law requires independent groups to register and publicly identify themselves as “foreign agents” if they receive any foreign funding and engage in broadly defined “political activity.” The term “foreign agent” in Russia is unambiguously negative and is understood to mean “spy.” The law is part of a broader government effort to discredit the work of civil society organizations and stigmatize them as acting in foreign interests, or even as traitors.[20] The law affected dozens of Russian human rights, environmental, women’s, and other groups.[21] In the six years since the law’s adoption, the government’s assault on civil society has escalated, and the atmosphere for civic activity has become increasingly hostile. This trend sharpened as Russia grew isolated internationally starting in 2014, following its military intervention in Ukraine.[22]

These trends also affected women’s rights and advocacy groups. Some leading women’s rights groups, including, for example, the ANNA Center, have been designated “foreign agents.” Others are working in a toxic atmosphere in which they fear being labeled as “foreign agent” and losing public trust. A leading lawyer who works on domestic violence cases said, “There is no activity left carried out by NGOs in this country that is not considered political and is not potentially penalized by the authorities.”[23]

|

The overall hostile environment has resulted in unwillingness, and even open fear, by public officials and public sector professionals to collaborate with foreign groups. For example, Human Rights Watch reached out to several government-run organizations seeking information about their work and about cooperation between various state agencies on addressing the issue of domestic violence. Several did not respond, and several declined to provide information or meet with Human Rights Watch researchers, openly stating that they feared the likely negative fallout of speaking with an international organization. “The geopolitical situation is changing so fast that I cannot predict the consequences of talking to you,” a senior staff member of one organization in the Ural region told Human Rights Watch.[24] |

II. Legal Framework

Serious gaps in Russia’s laws deprive women of protection from, and justice for, domestic violence. Russia does not have a federal law on domestic violence, and it is not recognized as a standalone offense in either criminal or administrative code.[25] Russian law does not provide for protection orders, that is immediate or longer-term measures to protect a potential victim from domestic abuse, including by barring contact between an alleged perpetrator and victim. Domestic violence prosecutions occur mostly if brought by private prosecution, placing the burden of investigation and prosecution on survivors of domestic violence.[26]

No Law on Domestic Violence

Despite over a decade of joint efforts by Russia’s civil society, rights’ advocates, and some policymakers, Russia does not have a national law on domestic violence.

There is no discrete provision or standalone offense of domestic violence, hence there is no definition in Russian law of domestic violence. There are two key reasons why this is problematic. First, it makes it difficult for law enforcement and courts to track the number of complaints, survivors, and cases of domestic violence. This results in a lack of comprehensive nationwide statistics and impedes anyone’s ability to assess the scope and dynamic of domestic violence. This, in turn, impedes the development of strategies and policies to combat and prevent domestic violence.

Second, legal experts and practicing lawyers agree that existing provisions that are used to prosecute domestic violence do not effectively capture the offense of domestic violence: that it often continues over a protracted period of time; the victim and perpetrator often live together, with the victim in many cases financially dependent on the perpetrator, and constantly vulnerable to risk of repeated violence; and the offenses often occur in private settings and are very difficult to independently corroborate.

As a women’s rights advocate said in an interview to Human Rights Watch:

The chances that someone gets assaulted on the street [by a stranger] over and over again by the same person are slim at best, whereas in situations of domestic violence, when the perpetrator and the victim often continue to live in the same apartment, it is almost guaranteed not only to repeat, but to escalate. Without legal safeguards in place, it can - and does - become much worse very quickly. [27]

Missed Opportunity to Adopt a Domestic Violence Law

Between 2012 and 2014, a group of practicing lawyers and legal experts discussed and drafted a federal law on combating and preventing violence within the family. The draft, which Human Rights Watch reviewed, introduced a definition of violence within the family, proposed measures to prevent domestic violence, provided for protection orders, and perhaps most significantly, for the transfer of domestic violence offenses from the sphere of private to public prosecution.[28]

The group worked in close consultation with several State Duma deputies, as well as officials from the Interior Ministry and the Ministry of Labor and Social Protection.[29] Both federal ministries reviewed and approved the draft; the Presidential Council on Human Rights also supported the draft and formally recommended that the State Duma adopt it.[30]

The State Duma, however, took no action on the draft. In September 2016, the working group again introduced the draft to the State Duma Committee on Affairs of Family, Women and Children, but the committee returned the draft to the authors citing procedural errors. A senior official who participated in the discussions of the draft, told Human Rights Watch that the claims of “errors” were arbitrary, bureaucratic pretexts, and that the committee rejected the draft because of a powerful pushback from religious leaders and other supporters of “traditional values.”[31]

Charges Used for Prosecuting Perpetrators

As mentioned above, Russian law does not distinguish domestic violence from other forms of violence against the person, such as battery or other types of assault. It addresses all of those through provisions on causing intentional harm to a person’s health that assign penalties depending on the severity of the harm to the victim.[32]

Specifically, first instances of battery that do not result in serious and lasting harm to health are an administrative offense under article 6.1.1 of the Code of Administrative offenses, with penalties ranging from 5,000 to 30,000 rubles (about US$80 to $478), up to 15 days of jail, or up to 120 hours of community service.[33] If committed within a year, a second such battery offense is punishable under Criminal Code article 116.1, with a fine of up to 40,000 rubles (about $590) or an amount not exceeding three months of the perpetrator’s income, or up to 240 hours of community service, or up to six months of corrective labor, or imprisonment for up to three months.[34] In some cases, authorities use Criminal Code article 115, which stipulates penalties for causing “light” - or insignificant - harm to health. Penalties under article 115 range from up to a 40,000-ruble fine (about $604) to up to four months in jail.[35]

These are the articles that are most commonly applied when domestic violence cases are investigated and prosecuted.

Acts of domestic violence that are “systematic” can also be prosecuted as the offense of “Torment,” under article 117 of the Criminal Code, although this rarely happens in practice.[36] Additionally, perpetrators of domestic violence can also be charged with offenses covered by other articles of the Criminal Code, including attempted murder, murder, grievous bodily harm or rape, but none of the perpetrators who had committed domestic violence against the survivors interviewed for this report were so charged. There are no publicly available disaggregated statistics or other official data to show the breakdown of how cases of violence in the family are prosecuted. No government agency responded to Human Rights Watch’s request for this disaggregated data.

Private Prosecution for Domestic Violence

Offenses charged under articles 115 and 116.1 under Russia’s Criminal Procedure Code are dealt with through the process of private prosecution (described in more detail below.)[37]

Under Russian law, private prosecutions are launched only if the injured party or their guardian takes the initiative to file a complaint with a magistrate judge. In such cases, the injured party bears the burden of gathering all evidence necessary for prosecution and must pay all costs of the prosecution.[38] This shifts the burden of ensuring justice for domestic violence entirely to the victim. According to ANNA Center, the majority of private prosecutions for domestic violence are terminated for lack of compliance with court requirements, or because of reconciliation between the plaintiff and the accused.[39] As described in section III of this report, the use of private prosecutions for domestic violence is an abdication of the state’s obligations to survivors of domestic violence, severely disadvantages survivors, and is a largely ineffective remedy for domestic violence in Russia.[40]

Protection Orders

Russian law does not provide for protection orders, whereby a presumed victim of domestic violence can get immediate or longer-term protection from perpetrators of domestic violence. A protection order could, for example, prohibit a perpetrator from contacting or being within a certain distance of the victim or require a perpetrator to leave a shared residence, among other measures. Russian law provides possible measures for witness protection, such as personal police protection, but courts frequently refuse to grant witness protection measures in even the most severe cases of domestic violence.[41]

When women do seek help from the authorities, they can become particularly vulnerable to further abuse. Human Rights Watch interviewed several women who continued to suffer harassment and severe abuse from their husbands and partners after, and often because, they reported violence to police and, in some cases, after they left abusive relationships. In one case, described below, an abusive spouse assaulted his wife 23 times over a 10- year period while they were married, including when she sued him for domestic violence and after she divorced him. Four of the assaults took place right outside a courtroom after a hearing in her case, when the man verbally abused and threatened the woman, pushed and grabbed her, and in one instance, punched her in the face.[42]

Protection orders in domestic violence cases are an internationally recognized means of ensuring immediate, sometimes life-saving, protection for victims of domestic abuse. International guidelines on protection orders recommend inclusion of the option to remove a domestic violence perpetrator from the home regardless of property ownership or tenancy.[43]

Decriminalization of Battery[44]

In February 2017, the Russian parliament adopted a law decriminalizing a first offense of non-aggravated battery within the family, relegating it to a mere administrative offense.[45]

Decriminalization of Battery, Creation of Domestic Battery Offense: July 2016

As noted above, in Russia, domestic violence is primarily addressed through Criminal Code offenses of battery and causing intentional harm to a person’s health, and the severity of the penalties depends on the degree of harm. Prior to July 2016, the Criminal Code offenses most often used to prosecute domestic violence offenses were “intentional infliction of minor harm” (article 115), and battery (article 116).[46]

In July 2016, the Russian State Duma adopted legal amendments to decriminalize non-aggravated battery.[47] The Russian Supreme Court, which initiated the legislation, argued that the amendments were necessary to “humanize” Russia’s criminal justice system, i.e.to introduce lesser criminal penalties for lesser offenses and lighten the criminal justice system’s burden.[48]

The legislation distinguished, for the first time in Russia’s post-Soviet history, between battery among non-family and domestic battery. First-time battery offenses among strangers became punishable under a new article 6.1.1 of the Administrative Code, with the penalties ranging from a minimum fine of 5,000 rubles (approximately $79) to up to 15 days of jail.[49] Battery among “close persons”, including spouses, parents, children, adoptive parents and adoptive children, siblings, grandparents and grandchildren as well as persons who “run a common household”, was made into a criminal offense, together with aggravated battery, and became subject to private-public prosecution (described in more detail below).[50] Penalties were strengthened: instead of a maximum three months’ jail time set out in the pre-July 2016 article 116, the new penalties ranged from 360 hours of community service to up to two years’ imprisonment.[51]

Russian lawyers working on domestic violence and expert groups welcomed the amendment and considered it to be a preventative measure against domestic violence. Many argued that the new amendment would lead to more timely detection and prosecution of domestic battery, and would therefore contribute to the prevention of more serious crimes, such as murder or serious harm to health.[52] The severity and certainty of criminal punishment, as well as the fear of criminal investigation, they argued, would serve as a much-needed deterrent for potential perpetrators.

Unfortunately, this aspect of the 2016 amendments was in effect for only six months, too short a period of time to see or measure its impact. One practicing lawyer commented: “That period of time was simply too short and there were a lot of complications that were not given enough time to [get] iron[ed] out. It was as though police and judges were playing football with domestic violence cases, tossing them back and forth and as a result, many perpetrators avoided punishment.”[53]

Undoing the Domestic Battery Provision: November 2016 - February 2017

In November 2016, a coalition of several Russian lawmakers, led by Senator Elena Mizulina, introduced a draft amendment to remove the first-time offense of battery within the family from the Criminal Code.[54]

Senator Mizulina had previously tried to stop the adoption of the family battery provision, arguing that there should be less government interference in family life. She further claimed that NGOs were part of a Western assault on Russia’s values and sovereignty, and the main supporters of the family battery provision. She accused them of deliberately misleading the public to secure increased funding:

“They . . . have a very mercantile interest in promoting this agenda. The thing is, Western countries have grant programs for NGOs that fight domestic violence. Because of this, a lot of topics are being forcefully included in the political agenda. This applies not only to groups that receive foreign funding. Russia has a lot of its own programs on the federal and regional level. NGOs inflate the importance of this topic in order to increase the overall funds allocated to fight the problem and also as part of competition for the existing ones. [55]

Mizulina and other deputies made several misleading and unfounded comments about the nature of domestic violence to support their claim that it should not be a criminal offense. Mizulina suggested that women “don’t take offense when they see a man beat his wife” and that a man beating his wife is “less offensive” than when a woman “humiliates a man.”[56] She and other parliamentarians also argued, with no evidence, that criminal sanctions for certain forms of domestic violence would disproportionately affect parents who use “spanking” to discipline their children.[57]

On February 1, 2017, Russia’s parliament adopted the amendment decriminalizing the first offense of domestic battery, and President Vladimir Putin signed it into law a week later. The amendments meant domestic violence, once again, was not officially mentioned or defined in legislation, whether administrative or criminal.[58] As a result of the amendment, a first offense of domestic battery is treated in the same manner as a first instance of battery between non-family members, under article 6.1.1. of the Administrative Code. If the offense is repeated within one year, as described above, it is dealt with under the revised Criminal Code article 116.1.[59]

Russian and international human rights groups sharply criticized the February amendments. The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNHCHR) and the CoE’s Human Rights Commissioner and its secretary general spoke out against it, with the latter calling it a “clear sign of regression.”[60]

Many Russian officials defended the law, claiming it “strengthened” families and reflected Russia’s public attitudes. The speaker of the State Duma, Vyacheslav Volodin, defended the legislation using misleading examples to suggest that the 2016 amendments had been a “mistake.” For example, he argued, “If two brothers fought, it was penalized with criminal sanctions. If a man fought with his neighbor, it was an administrative offense. You can see that we needed to correct that mistake.”[61] In another interview, Volodin noted that according to public opinion polls, 60 percent of respondents supported the decriminalization of a first domestic violence offense and asserted that the Duma has a responsibility to reflect public opinion. He also said that while protection from domestic violence was necessary, this had been accomplished “through dialogue.”[62]

A top official in United Russia, the ruling party, also argued that the Duma majority made the right choice. By passing the law, he said, using another misleading example, “The Duma is correcting an injustice that existed until today... If, say, a single mother returns home from her second job and finds narcotics in her son’s nightstand, and in the heat of the moment gives him a slap, until today she would be a criminal by terms of the Criminal Code. And if her son hits someone on the street, he’s not a criminal, it’s an administrative offense at maximum. The same action carries different penalties. That’s out of line with the Constitution.”[63]

In these debates, politicians ignored fundamental differences between violence among strangers and domestic violence that are noted above: that in the latter, perpetrators frequently repeat their offenses, and that victims often live with their abusers and are often financially and otherwise dependent on them. They also ignore the psychological or emotional and verbal abuse, and manipulation that typically accompany the physical abuse. Lawyers and women’s rights groups working on domestic violence noted this when they spoke out against the new legislation. They also noted that if perpetrators of domestic violence were not held accountable before the 2016 and 2017 amendments, then downgrading the offense from criminal to administrative liability would embolden them, not encourage them to stop.

The head of Nasiliu.net, (a play on words for “no” to violence), Anna Rivina, said that the new law put beatings, which caused physical and psychological harm, “in the same category as a parking violation or smoking in a place where it’s prohibited.”[64]

Officials’ arguments for decriminalizing domestic violence also ignored the fact that domestic violence often occurs as a series of episodes that tend to escalate.

|

Polina’s Story

45-year-old Polina lived with her husband and their daughter, 6, and son, 10, in Moscow region. Polina’s husband became aggressive and violent soon after their son was born in 2008. At the time, Polina was on maternity leave and was financially dependent on her husband, who started psychologically abusing her through constant, unfounded demands and accusations as well as depriving her of sleep. He then started hitting Polina. Polina tolerated the abuse because her husband apologized after each incident and she hoped that the situation would improve. In June 2017, the husband attacked Polina and attempted to choke her. He dragged her across the floor by the leg, causing a serious knee injury, and threatened to throw her out the window and make it look like suicide. He then raped Polina. Polina ran from home to a shelter and filed for divorce. [65] |

In a case, described by the deputy director of the ANNA Center, Andrey Sinelnikov, a woman in Nizhniy Novgorod in 2015 reported repeated violence by her husband to the police, who took no action. The man went on to kill his wife, his mother, and six small children. Sinelnikov noted that if the police had opened a criminal case in a timely manner, the mass murder could have been prevented. [66]

[67]|

Figure 1: Changes in legislation concerning battery |

||||

|

|

How battery is classified |

Separate mention of domestic violence |

Laws |

Penalties and prosecution |

|

Prior to July 3, 2016 |

Criminal offense |

No |

Battery: Criminal Code Article 116 |

Fines of up to 40,000 rubles or an amount not exceeding three months of the perpetrator’s salary or other income of the perpetrator or; up to 360 hours of community service or; up to 6 months’ corrective labor or; up to 3 months’ jail; private prosecution |

|

July 3, 2016-February 6, 2017 |

Battery among “close persons” criminalized. Other forms of simple nonaggravated battery are moved to the Administrative Code

|

Yes |

Criminal Code Article 116 (Battery among “close persons”). |

Up to 360 hours of community service or; up to 1 year of corrective labor or; up to 2 years’ restriction of liberty; up to two years’ forced labor or; up to 6 months’ jail or; up to 2 years’ imprisonment; private-public prosecution

|

|

|

New article 116.1 of the Criminal Code is introduced, penalizing repeated battery within a year |

|

Article 116.1 (Repeated battery)

|

Fine of up to 40 000 rubles or an amount not exceeding three months of the perpetrator’s salary or other income of the perpetrator or; up to 240 community service or; up to six months of corrective labor or; up to three months jail; private prosecution

|

|

|

|

|

Administrative Code Article 6.1.1 (Battery) |

Fines of 5,000 to 30,000 rubles or; 10 to 15 days in jail or’ 60 to 120 hours’ community service; administrative proceedings |

|

February 7, 2017 Onward |

All instances of simple battery that occur no more than once per year are classified as administrative offenses

|

No |

Administrative Code Article 6.1.1

|

Fines of 5,000 to 30,000 rubles or; 10 to 15 days in jail or’ 60 to 120 hours’ community service administrative proceedings

|

|

|

Aggravated battery or simple battery occurring more than once per year is a criminal offense |

|

Criminal Code Article 116 (aggravated battery).

|

Up to 360 hours of community service or; up to 1 year of corrective labor or; up to 2 years’ restricted liberty or; up to 2 years’ forced labor; or up to 6 months’ imprisonment; or up to 2 years’ imprisonment; private-public prosecution

|

|

|

|

|

Article 116.1 (repeated battery) |

Up to 40 000 rubles fine or an amount not exceeding three months of the perpetrator’s salary or other income or; up to 240 community service or; up to six months of correction labor or; up to three months jail; private prosecution |

Impact of Decriminalization

The 2017 legislative amendments led to additional, serious setbacks and barriers for survivors of domestic violence in accessing justice and protection:

- They fostered a sense of impunity for abusers by giving them a “green light” that beating family members was no longer a criminal offense;

- They weakened protections for victims by reducing penalties for abusers;

- They created new procedural shortcomings in prosecuting domestic violence.

Green Light to Violence

Experts and officials who supported decriminalization had argued that it would not lead to an increase in violence, as long as domestic violence remained an administrative offense and as long as a second offense within a year would be a criminal offense. Lawyers and rights advocates, however, had predicted that the 2017 legislation would result in more assaults, due to there being fewer factors deterring offenders.

Days after the decriminalization amendments were adopted, the mayor of Russia’s third largest city, Yekaterinburg, told the media that police had responded to more than twice as many domestic violence incidents as usual. “People got the impression that before it wasn’t allowed,” the mayor said, “But now it is.”[68]

A year after the law was adopted, some say their predictions have become a reality.[69] This assessment was partially shared by some senior government officials, including the head of Russia’s lead investigative agency, Alexander Bastrykin, who in May 2018 criticized the decriminalization, saying it had resulted in a “sharp increase in family violence offenses, including against children.”[70]

Most women rights’ groups and crisis centers interviewed for this report noted an increase in the number of domestic violence complaints after the 2017 amendments were enacted and said that they considered the increase to be a direct effect of decriminalization. Some groups did not attribute the fluctuation in the number of complaints to the changes in legislation. Another reason given for the rise in complaints was that women had become more sensitive and aware of their rights in response to domestic violence and that more were trying to seek help when first signs of physical or psychological violence appear. Most groups agreed that there had been an increase in awareness of the issues.

For example, staff from the ANNA Center told Human Rights Watch that the center received significantly more calls on their hotline after the 2017 legislation, suggesting a correlation with media coverage of the decriminalization legislation and more survivors coming forward seeking advice on ways to obtain assistance.[71] The head of the Crisis Center for Women in Saint Petersburg said that the number of calls to the center continued to steadily increase over time: in 2015, over 3,000 people requested help through the group’s hotline and office hours, and in 2017 it was over 6,000.[72]

Staff from the Archangelsk Crisis Center, who also respond to calls on the national hotline for survivors of domestic violence, said that the number of complaints fluctuated in the usual pattern, irrespective of the legislative changes. For example, they said, there was always an increase in calls following national or regional campaigns raising awareness about domestic violence.[73]

Reduced Penalties

According to statistics provided by the Justice Department of the Supreme Court, punishment for battery offenses became more frequent following decriminalization. In 2015 and 2016, 16,198 and 17,807 persons respectively were convicted for criminal (non-aggravated) battery.[74] Throughout 2017, 113,437 people were sentenced for battery as an administrative offense.[75] This data does not differentiate between battery within the family and in other circumstances.

Also according to official data, in 2017, the majority of perpetrators of battery, 90,020 out of 113,437, were fined.[76] However, several women noted to Human Rights Watch that when a court issued their abusers a fine the abuser paid the fine from the family’s shared bank account.

Survivors, experts, and women’s rights activists told Human Rights Watch that the new penalties for a first offense of battery, a minimum 5,000 rubles fine (approximately $79) or 15 days in jail, are ineffective and insufficient. They said that fines are particularly ineffective as a deterrent for perpetrators of domestic violence.[77]

Mari Davtyan, a leading human rights lawyer working on domestic violence cases and Anna Rivina, the head of Nasiliu.net noted that administrative penalties do nothing to protect victims:

Punishing perpetrators for administrative offenses does not protect or restore the rights of victims, and a fine of 5,000 rubles is not a sufficient deterrent for offenders who saw the transfer of battery to an administrative offense as permission to abuse. Yes, our system has never really effectively protected victims of domestic violence. Nonetheless, decriminalization does not represent a step forward, but rather a huge leap back.[78]

Some senior government officials also recognized this as a problem. For example, in December 2017, Interior Minister Vladimir Kolokoltsev stated: “In more than 70 percent of administrative cases on battery, courts impose fines, which does not correspond with the punitive purpose of punishment. Frequently, this measure does not serve as prevention and when we are talking about family members, it also imposes additional burden on the family.”[79]

New Procedural Challenges

Lawyers who represent survivors of domestic violence said that the new law made it significantly harder for women to take their abusers to court. In order to initiate an administrative case against a perpetrator under article 6.1.1, the victim files a complaint with police, who, after registering and looking into the complaint, draw up an administrative offense report and pass it on to court.[80] The law allows the victim to appeal if police decide not to initiate administrative proceedings, provided that the police issue a statement on their negative decision.[81] However, in most of the cases Human Rights Watch documented for this report, the police provided complainants no written statement when deciding not to initiate an administrative procedure, thereby depriving women of the capacity to appeal. Notably, Russia’s Criminal Code envisages appealing actions and “lack of action” by officials, but there is no analogous provision for appealing “lack of action” in administrative cases.

For example, Galina Ibryanova, a human rights lawyer from St. Petersburg with many years of experience providing pro bono legal services to survivors of domestic violence, told Human Rights Watch about the procedural difficulties her clients faced after the February 2017 legislation:

It is extremely difficult to initiate an administrative case against a domestic abuser. Dozens of my clients tried during that time [after decriminalization] to go through the motions: file a police complaint, gather all the necessary documents, get official confirmation of injuries… but most got zero response. They simply don’t have any idea what happened to their complaints. And I’ve never heard of such an exotic situation in which the police provided a client with a written statement refusing to initiate an administrative case. That, of course, now makes any kind of appeal impossible.[82]

She concluded that the new legislation is a “catastrophic mistake.” [83]

Irina’s Story: An Example of the Harmful Impact of Decriminalization

Human Rights Watch documented several cases in which the 2017 legislative amendments harmed survivors of domestic violence and in some cases, let perpetrators escape justice. One of the more striking cases is the case of Irina Petrakova, a career development professional from Omsk.

|

Irina’s Story Irina, 36, had been married to Alexey, a successful engineer from Moscow, for two years when he first hit her in 2007. At the time, she was seven months pregnant with their daughter.[84] He punched her in the stomach several times. Because Alexey had never previously exhibited any signs of violence, and because the attack was so sudden and inexplicable, she thought she must have done something wrong. Three years later, when Irina was pregnant with their second child, Alexey beat her again, this time in front of their two-year-old daughter. Afterwards, Irina left Alexey. He begged for forgiveness and promised to get psychological help. Irina returned to him, not wanting to leave her children without a father. In 2012, Alexey beat her again. Later, he hit their three-year-old son and punched Irina in the face when she tried to defend the boy. Irina sought help from her friends and family, who advised her to wait for things to get better or suggested that she had “provoked” Alexey. Irina also sought help from a psychologist, who suggested that things would get better after the children got a little older. Instead, Irina said, the beatings intensified and became more frequent. Irina said that beatings occurred suddenly and without warming: “Anything could trigger it. Anything could cause him to ‘lose it’. Maybe I looked at him the wrong way or laughed in a wrong place. Once, it was because he couldn’t exit a parking lot because there was too much traffic... but after each incident, it was like something released in him. He could joke, play with the children. Until the next time.” In September 2014, Alexey brutally beat her in front of their children, then aged six and four, hitting her over 40 times on her face and body. Irina was hospitalized and diagnosed with a brain injury, multiple bruises and hematomas on her legs, arms and body. She filed for divorce, which took several months, with the magistrate judge urging her three times to reconcile with Alexey. Over the next seven months, Alexey beat and threatened Irina 18 times. She was repeatedly hospitalized with concussions, severe bruises, and hematomas. One of the most severe beatings resulted in two nails on her left hand being torn off. Alexey also sexually assaulted and raped Irina. Throughout 2014 and 2015, Irina filed eight complaints with the police and eight times the police refused to open a criminal investigation. Irina had moved out, but Alexey stalked and assaulted her several times. She and her lawyer were unable to get the police to protect her. [85] Irina also filed three battery complaints with a magistrate judge, who started considering her case only in 2015, although she filed the first complaint in 2014. In July 2016, the Russian parliament adopted the first series of amendments decriminalizing battery, and the magistrate dropped two cases against Irina’s husband, because the beatings under those two cases occurred after Irina and her husband were divorced, prompting the judge to find that these instances were no longer covered by article 116 of the Criminal Code. Eventually, Irina and her lawyer initiated a case against her husband on charges of “torment,” a very rare classification for domestic violence offenses in Russia. The case was later divided into four criminal cases. Between 2015 and 2016, Irina’s husband continued to stalk her and attacked her several times, including four times outside a courtroom. The court ruled that a general amnesty issued by parliament was applicable in one case and dropped the charges against Alexey.[86] In two other cases, criminal charges were dropped as a result of the 2017 amendments decriminalizing first time battery. In the last case, the court convicted Irina’s husband, but only sentenced him to 120 hours of compulsory community service. Irina lost all appeals and is currently preparing to file a complaint with the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR). |

III. Access to Protection

I lived with him for ten years and was married for five. Our son was four when we divorced. He humiliated me, pushed me around. Once he hit my head against a sharp corner of the wall and forced me out of the flat while the wound on my head was pouring blood. But while we were together, I knew I had to bear it, be patient, because I kept thinking that things were not “that bad” and that maybe everyone lived like that and other women had it even worse. We were very well off financially, both professionally successful, and I thought I needed to do everything I could to keep the family together…If someone knew about our problems, it would be so embarrassing. The problem is this mentality, that generations before you had, who believed [that you have to put up with it] and have taught us to believe the same… I lost years of my life because of such thinking. And, I just did not know that there was help out there. If I knew about the crisis apartment, for example, I would have left him much earlier and my son would not be as psychologically traumatized now.

—Antonina, 33.[87]

Barriers to Reporting Domestic Violence

Official studies suggest that only around 10 percent of survivors of domestic violence in Russia report incidents of violence to the police.[88] According to experts’ estimates, between 60 and 70 percent of women who suffer family violence do not report it or seek help.[89] Only around 3 percent of domestic violence cases make it to court.[90]

Domestic violence is largely unreported in Russia due to several key factors. These include social stigma attached to the issue, which public officials, including law enforcement and judges, often reinforce through their rhetoric; overwhelming lack of awareness about domestic violence and available services among survivors themselves, their immediate family and friends, and also in some cases by social service providers; lack of trust in police and poor police response; victims’ fear of retaliation by their abusive partners; and fear of losing custody of their children.

The police frequently treat victims of domestic violence with open hostility and refuse to register or investigate victims’ complaints of domestic violence, often arguing that women themselves have “provoked” the violence. Survivors who do persist in bringing a case to court have to follow the deeply burdensome process of private prosecution, which requires legal expertise and a significant time and financial commitment, with all the labor and costs borne by the victim. A leading lawyer working on domestic violence cases told Human Rights Watch that the majority of private prosecutions of domestic violence are terminated for lack of compliance with court requirements or because of the parties’ reconciliation.[91]

Lack of Awareness, Social Stigma, Victim Blaming

A range of misconceptions about domestic violence and stereotypes about victims are pervasive in Russian society. While researching this report, Human Rights Watch came across the following beliefs and remarks—reported by survivors, lawyers, staff working in shelters and crisis centers—as said by law enforcement, politicians, psychologists and judges: “domestic violence is a private matter;” “women provoke the violence, and they deserve it;” “arguments between spouses are natural and should not result in any serious consequences;” and women should strive for “reconciliation and preservation of the family unit,” even in cases of violence. In several cases described below, police declined to take action on women’s reports of domestic violence, because, they said, the situation was a “family matter.”

As mentioned above, opinion polls conducted in recent years suggest that while Russians’ views on domestic violence are changing for the better, many still view domestic violence as a private matter between couples.[92] This view, not unique to Russia, creates barriers for reporting abuse, encourages families to shield abusers, and stigmatizes those who report to the authorities and “publicize” the abuse. Many survivors interviewed for this report admitted to experiencing a strong feeling of shame that held them back from reporting their situation to the police or even sharing it with family or close friends.

Survivors of domestic violence who do try to report abuse are often met with condemnation and stereotypes from family members and authorities alike. A psychologist with the St. Petersburg Crisis Center for Women told Human Rights Watch about one of her clients who was abused by her spouse:

She had three concussions in two months… Two were very bad. He just wrapped her hair around his fist and hit her head against the wall... And she told me that when she came to file the complaint with the police, the investigator, who was a woman, said to her: ‘Something must be wrong with you. My husband doesn’t beat me.’ There is this strong belief, even among women, that if your husband beats you, it’s somehow your own fault.[93]

Survivors who come forward are often accused of wanting to destroy their family and deny their children a father. The myth that women “provoke” or “deserve” violence is widespread and encourages victim-blaming, and even mocking, by police and relatives.

For example, in 2016, Yulia, from a small town in western Russia, complained to the police after her husband severely beat her. The police officer who responded came to her flat and talked to her husband. They spoke for several minutes in the kitchen, and then she heard them laughing and referring to her as a “dumb broad.” The policeman then came out and told her to make peace with her husband. After he left, the husband, furious at her for calling the police, beat her again and broke her jaw. He then left for several months with their eight-year-old son.[94] She called the police again who suggested, mockingly, that she was “sour” because the husband must have left her for another woman.[95]

High-level officials, law enforcement, and judges considering domestic violence cases frequently use rhetoric that embraces myths and stereotypes, or that demonstrates a disturbing lack of awareness about domestic violence. For example, Russia’s former children’s rights commissioner, Pavel Astakhov, suggested that the term “family violence” should not be used frequently as it intimidates families and parents.[96] Other examples can be found in survivors’ stories elsewhere in this report.

Survivors of domestic violence who have children face the stigma of leaving their children “fatherless” if they come forward. For example, Alyona, from Samara region, was severely beaten by her live-in partner for five years, between 2013 and 2017. He started beating her when she was pregnant with her first child. After her son was born, Alyona did not want to get pregnant again, fearing her partner would become more violent, and began avoiding physical intimacy with him. He then raped her repeatedly and she became pregnant with twins. After giving birth, Alyona was unable to return to work and had no means to support herself, while the beatings continued, and her partner continued to rape her. She became pregnant again and gave birth to a daughter. She filed several complaints with the police but received no protection. Additionally, when she described her situation to the local child protection services, they told her that her four children “needed a father” and that it would be difficult for her to raise the children alone.[97]

Lack of Awareness

Due to widespread victim blaming and stigmatization of survivors of domestic violence, some women are simply not aware that domestic violence is wrong and that they have the option of seeking help. This results in women finding help in a roundabout way; as the head of the Arkhangelsk center put it in an interview with Human Rights Watch, “it’s a quest.”[98] Liza from Pskov, for instance, said that it took her months to find specialized help.[99] Faced with violence at home, she initially felt that it was her “own fault” and sought help from her parents and her partner’s parents. When asked why she did not go to a shelter right away, she said that she did not understand domestic violence in general, or services available for survivors:

When I first came to see someone, it was a doctor, a gynecologist. She suggested that my problems could be due to stress and recommended that I see a psychologist. When I went to the psychologist, I asked her to please help me save my family and teach me how to be a better wife. I didn’t even realize the situation I was in. Eventually she directed me to this center. If I knew then that such a problem exists in our society, and many people face it, and there is nothing to be ashamed of, and there is help, I would have come for help a lot sooner.[100]

Social stigma and lack of awareness about domestic violence is of particular concern in the more remote regions of Russia, where getting help is more difficult, and domestic violence is viewed as a normal part of everyday life.

A woman who grew up in a village in Chuvashia told Human Rights Watch that as a child, she witnessed her uncle repeatedly and brutally beating her aunt. Every time before the beating, the aunt told the children to go outside and to not come in under any circumstances. The woman, who later in life was abused by her own husband, said that everyone in the village knew about it but no one did anything because it was considered normal part of “life in a village.”[101]

Fear of Reprisals, Lack of Trust in Police

Most interviewees said that even when they did call the police, they did not receive the protection they needed. In some cases, the police did not arrive at all, and in others they refused to take action, suggesting that it was a “family matter.” Women also told Human Rights Watch that they feared reporting their abusers to the police because they thought that it may result in more violence. The state authorities’ failure to adequately protect victims from being further harassed, threatened, or abused in retaliation for coming forward puts victims at risk of further, potentially grave, and even fatal violence and may deter others from coming forward.