(Erbil) – Iraqi military and security forces have disappeared dozens of mostly Sunni Arab males since 2014, including children as young as 9, often in the context of counterterrorism operations, Human Rights Watch said in a report released today.

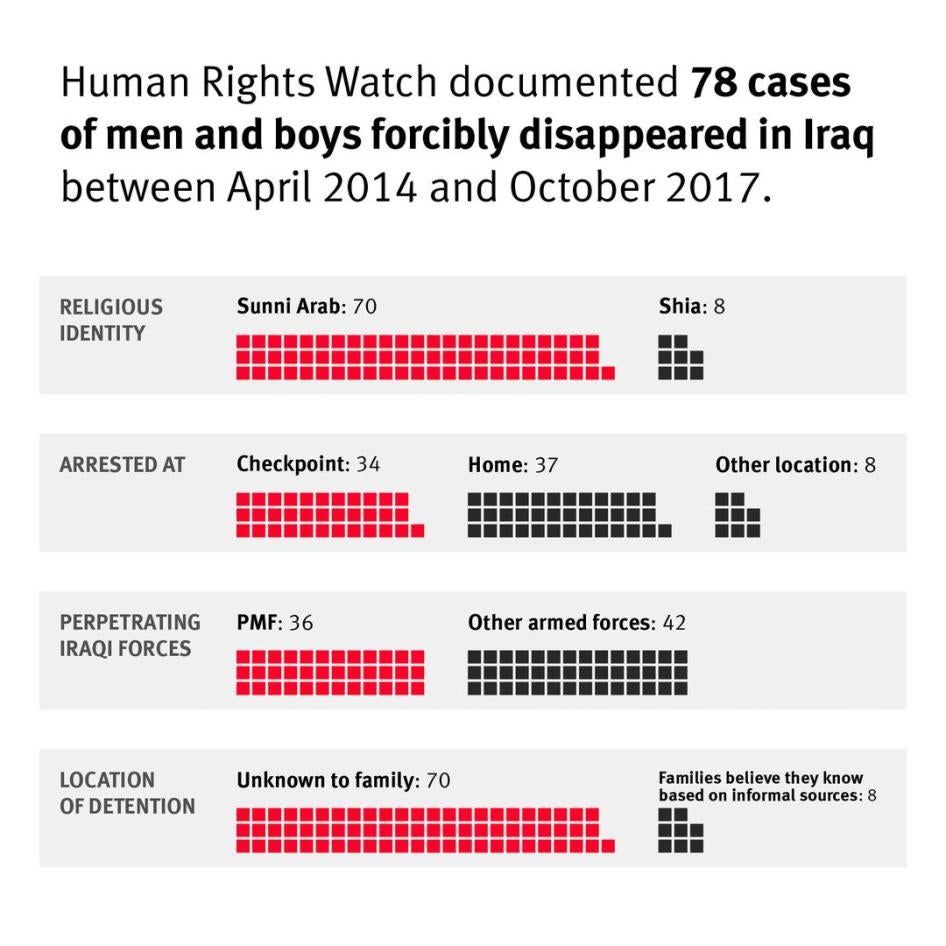

The 78-page report, “‘Life Without a Father is Meaningless’: Arbitrary Arrests and Enforced Disappearances in Iraq 2014-2017,” draws on research Human Rights Watch has published on enforced disappearances in Iraq since 2014, when Iraqi forces launched anti-ISIS operations, and documents an additional 74 cases of men and four cases of boys detained by Iraqi military and security forces between April 2014 and October 2017 and forcibly disappeared. The enforced disappearances documented are part of a much wider continuing pattern in Iraq. Iraqi officials have failed to respond to inquiries from the families and Human Rights Watch for information about the disappeared.

“Families across Iraq whose fathers, husbands, and sons disappeared after Iraqi forces detained them are desperate to find their loved ones,” said Lama Fakih, deputy Middle East director at Human Rights Watch. “Despite years of searching, and requests to Iraqi authorities, the government has provided no answers about where they are or if they are even still alive.”

The International Commission on Missing Persons, which has been working in partnership with the Iraqi government to help recover and identify the missing, estimates that the number of missing people in Iraq could range from 250,000 to one million people, with the International Committee of the Red Cross stating that Iraq has the highest number of missing people in the world.

Human Rights Watch drew on research it has published on enforced disappearances since 2014, and carried out additional interviews from early 2016 to March 2018 with the family members, lawyers, and community representatives of the 78 currently identified as forcibly disappeared, as well as three who had themselves been disappeared and were subsequently released. Researchers reviewed court and other official documents relating to the disappearance cases.

Enforced disappearance is defined under international law as the arrest or detention of a person by state officials or by agents of the state or by people or groups acting with the state’s authorization, support, or acquiescence, followed by a refusal to acknowledge the arrest or to reveal the person’s status or whereabouts. The prohibition also entails a duty to investigate cases of alleged enforced disappearance and prosecute those responsible.

The enforced disappearances documented were carried out by a range of military and security entities, but the highest number, 36, were by groups within the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF), units under the prime minister’s command, at checkpoints across Iraq. Witnesses said at least 28 of these were carried out by the Hezbollah Brigades.

The wife of “Hardan,” 42, whose husband was arrested in 2014, said that the Defense Ministry, where he worked, is only paying her half his salary since she can’t produce a death certificate or proof of incarceration. She struggles to keep up with expenses and raise her sons.

Human Rights Watch sent questions and a list of the disappeared and the approximate dates and locations where they were last seen for the cases documented to the human rights adviser to the Prime Minister’s Advisory Council in Baghdad and the Kurdistan Regional Government’s coordinator for international advocacy. On September 18, the Kurdistan Regional Government responded with information about the number of individuals detained for ISIS affiliation and its arrest procedures. It did not respond to any of Human Rights Watch’s specific queries, including on the whereabouts of individuals included in the report. Baghdad authorities provided no response.

The majority of the 78 people whose cases Human Rights Watch documented were detained in 2014, with the most recent in October 2017. But Human Rights Watch has continued to receive reports of additional disappearances across Iraq. In three more cases, men who were detained and disappeared in 2014 and 2015 had been released. They indicated that they had been detained by the PMF or the National Security Service in unofficial detention sites, and all said they had been beaten throughout their time in detention.

Military and security forces apprehended 34 of the men and boys at checkpoints as part of anti-Islamic State (also known as ISIS) terrorism screening procedures and another 37 at their homes. All of the disappearances at checkpoints but one targeted people who are from or lived in areas that were under ISIS control. In most cases in which people were arrested at home, the security forces gave the families no reason for the arrests, although the families suspect the reasons were related to the detainees’ Sunni Arab identity. In at least six of these cases, the circumstances or what arresting officers said indicated that they were at least potentially related to the fight against ISIS.

Of the families interviewed, 38 requested information regarding their missing relatives from Iraqi authorities but received none. Other families had not sought information, fearing inquiries would seriously jeopardize their relatives’ safety. None of the families had a clear idea of which authority they should contact to find out their relatives’ whereabouts.

Under Iraqi criminal procedure, police may detain suspects only with a court-issued arrest warrant and must bring suspects before an investigative judge within 24 hours to mandate their continued detention. In the cases documented, families and witnesses said that security officers did not present search or arrest warrants. None of the families knew whether their relatives had been brought before a judge in the allotted amount of time.

In three cases, family members alleged that the arresting officers used excessive force, in one case leading to a death of another relative.

The International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance, to which Iraq is a party, codifies the prohibition on enforced disappearances and, among other things, sets out the obligations of states to prevent, investigate, and prosecute all enforced disappearances. Iraq was meant to submit a report on the state’s implementation the convention by September 18, 2018. Human Rights Watch was unable to determine whether it has submitted the report to the Committee on Enforced Disappearances yet.

Iraq’s new federal government, which is expected to be established in the coming weeks based on the May elections, and the Kurdistan Regional Government should make combatting enforced disappearances and investigating past incidents a priority, to show their commitment to respect and protect the rights of all populations in Iraq. Authorities should establish an independent commission of inquiry to investigate enforced disappearances and custodial deaths nationwide in all official and unofficial detention facilities.

Anyone still in detention should be charged or released. If they have died, the authorities should return their bodies to the families and provide full details of the circumstances. Any state forces implicated in abuse should be investigated and punished, and families should receive reparation.

The United States, United Kingdom, Germany, France, and other countries providing military, security, and intelligence assistance to Iraq should urge authorities to investigate allegations of enforced disappearances and should investigate the role of their own assistance in these alleged violations. They should suspend military, security, and intelligence assistance to units involved until the government adopts measures to end these serious human rights violations.

“The US-led coalition and other countries have spent billions of dollars on Iraq’s military and security entities,” Fakih said. “These countries have a responsibility to insist that the Iraqi government should call a halt to disappearances and provide support to victims’ families.”