The Manipur authorities and police should cease the harassment and fully cooperate with the ongoing investigations ordered by India’s Supreme Court, Human Rights Watch said.

“The Supreme Court’s intervention to investigate alleged wrongful killings by security forces sparked hope for justice for families of hundreds of men, women, and children in Manipur and an end to the culture of impunity,” said Meenakshi Ganguly, South Asia director at Human Rights Watch. “In a clumsy yet predictable effort to deter inquiries, the security forces have attempted to intimidate activists and victims’ families. The authorities should redouble their efforts to investigate these killings and prosecute those responsible.”

On April 7, 2018, Salima Memcha, whose husband was killed by alleged Assam Rifles members in 2010, wrote to the director general of police in Manipur to say that she was threatened and harassed by police commandos who came to her home in Thoubal district that morning. Memcha, who is a member of the Extrajudicial Execution Victim Families Association (EEVFAM), a petitioner in the 2012 Supreme Court case, said the police action “is the direct reprisal of my effort for seeking justice.”

Instead of trying to protect those responsible for egregious abuses, the authorities should cooperate with investigations and repeal the AFSPA.

South Asia Director

Memcha said that the police came to her house at 5 a.m., searched her home for half an hour, handled her personal belongings roughly, took her photo, and threatened her with “dire consequences.” She said that the police search prevented her from traveling to Imphal, the state capital, that day to depose before the state Criminal Investigation Department (CID), investigating her husband’s killing. Apart from the CBI’s investigation, Manipur state’s CID is also investigating several cases of alleged extrajudicial killings by security forces, including that of Memcha’s husband.

Ranjeeta Sadokpam, an activist with Human Rights Alert, which is also a petitioner in the Supreme Court case, said that at 1 a.m. on February 27, police and army personnel entered her home along with a masked man. In a written complaint to the director general of police, she alleged that the security personnel demanded to see identity documents for all her family members and forced them to sign a document, without showing them its contents.

On February 8, at about 3 a.m., three police commandos allegedly entered the home of activist Manoj Thokchom without an arrest or search warrant, detained, and interrogated him. Thokchom, founder of the Manipur-based Human Rights Initiative for Indigenous Advancement and Conflict Resolution, contributed to the petition on extrajudicial killings submitted to the Supreme Court in 2012. Thokchom alleged he was held for 15 hours and questioned about links to armed groups and his involvement in the Supreme Court case.

Sagolsem Menjor Singh, another member of EEVFAM, whose son was allegedly killed by the security forces in 2009, asserted that on January 8 at 6:30 a.m., police came to his house to arrest him. He was not home and his wife said that the police refused to show her a warrant. In a letter to the state’s chief minister on February 8, Singh asked for a copy of the warrant against him, or else requested the authorities to take strict action against the police officials involved in the harassment.

Okram Nutankumar Singh, an advocate who has assisted families of victims of extrajudicial killings, said that on October 14, 2017, at about 8:30 p.m., he heard a gunshot seemingly fired at his house. He filed a complaint the next day, but says the police have yet to investigate the case.

In Memcha’s case, the superintendent of police from Thoubal district told the news website Scroll.in that police had visited her home as part of a “routine cordon and search operation” and that it was standard procedure to conduct such operations at dawn.

The authorities in Manipur should ensure that victims’ families, witnesses, and advocates are protected and ongoing investigations by both the CBI and state CID are conducted in a fair, transparent, and time-bound manner, Human Rights Watch said.

The Supreme Court’s 2017 order followed its landmark decision in July 2016 that any allegation of use of excessive or retaliatory force by uniformed personnel resulting in death requires a thorough inquiry into the incident. The court added that such force was not permissible even “against militants, insurgents and terrorists.”

Lack of accountability

The court also noted that the state police not only failed to file first information reports (FIRs) against any police officers or other security force personnel in these alleged extrajudicial killings, but instead only registered FIRs against the deceased accusing them of being militants. The government and the army had opposed any investigation into the killings, asserting that all those killed were militants who died in counterinsurgency operations. The army said it cannot be subjected to investigations for carrying out counterinsurgency operations in violent areas like Jammu, Kashmir, and Manipur.

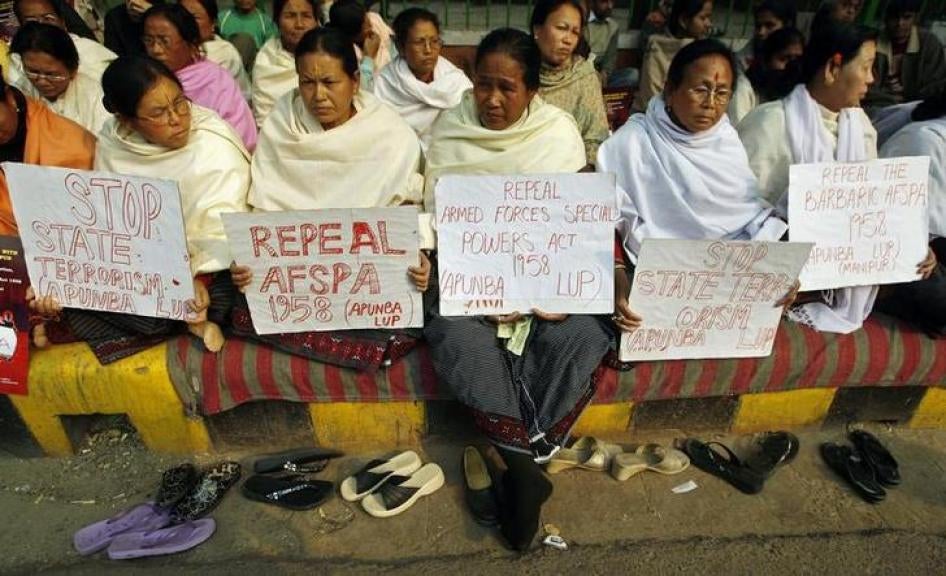

The absence of accountability for serious abuses has become deeply rooted in Manipur because of the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA), the 1958 emergency law under which the armed forces are deployed in internal conflicts and have broad powers to arrest, search, and shoot to kill. The law, which provides soldiers who commit abuses effective immunity from prosecution, is also used in other parts of India’s northeastern region and in the state of Jammu and Kashmir. The AFSPA has fostered a culture of violence that has encouraged similar abuses by the Manipur state police, Human Rights Watch said. In 2004, Manipuri mothers stripped in front of the Assam Rifles headquarters to protest an extrajudicial killing and called for the repeal of AFSPA. Several government-appointed commissions and international bodies have also recommended that the draconian AFSPA be repealed.

In a September 2008 report, “These Fellows Must Be Eliminated,” Human Rights Watch documented human rights abuses by all sides in Manipur, where close to 20,000 people have been killed since the insurgency began in the 1950s.

“Many in Manipur have long campaigned for an end to human rights violations, and the Supreme Court-ordered investigation offers some hope for justice and accountability,” Ganguly said. “Instead of trying to protect those responsible for egregious abuses, the authorities should cooperate with investigations and repeal the AFSPA.”