Why did you write this book?

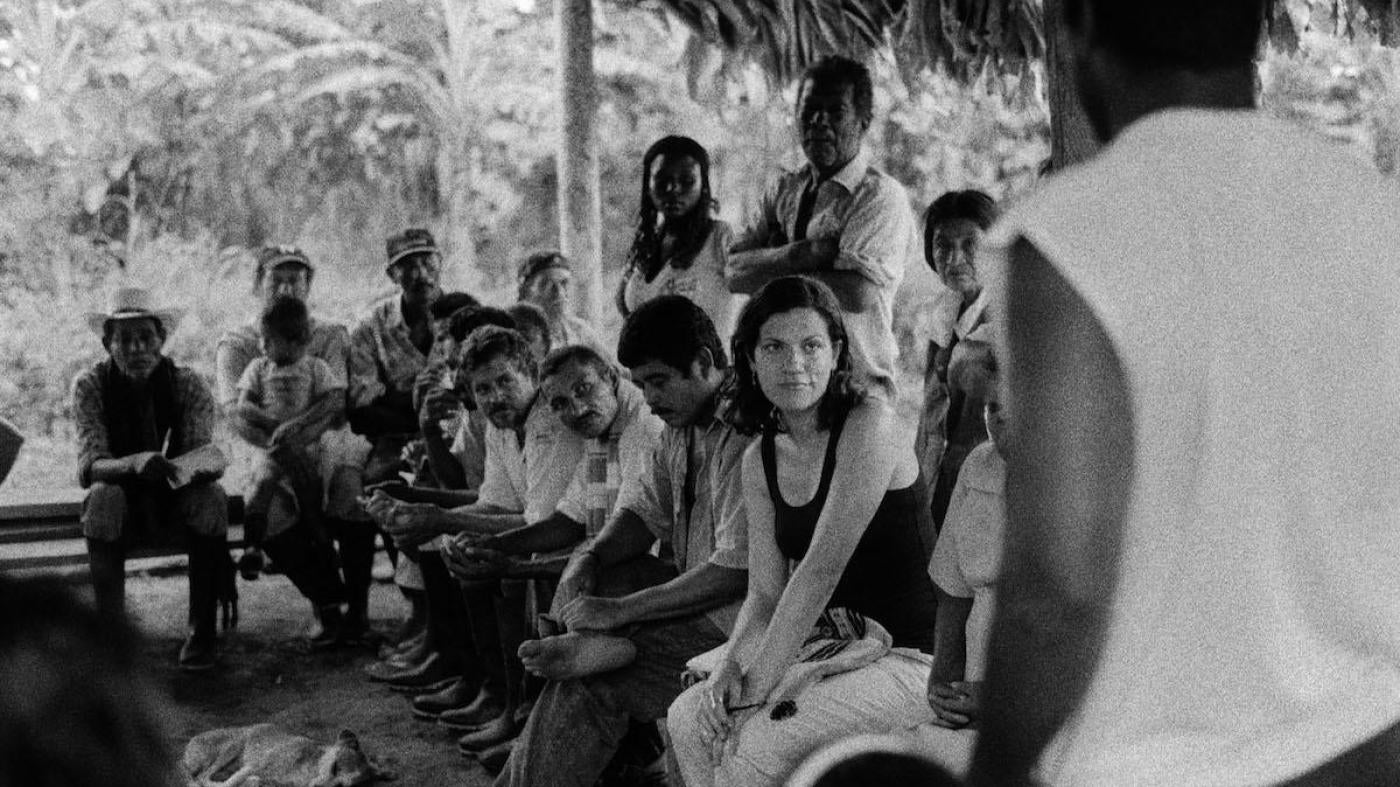

When I finished working in Colombia in 2010, I had a lot of stories that I hadn’t been able to tell. I had met many brave ordinary Colombians who stood up to the paramilitaries and other armed groups, but many people didn’t know about their stories or courage.

Who are the paramilitaries?

The paramilitaries had been private armies formed by wealthy people – both to fight guerrillas and to further the wealthy people’s interests -- to take land, to kill trade unionists or others who got in their way, and so on. From the beginning, many of them worked closely with major drug traffickers, including Pablo Escobar. In fact, after Escobar’s death they became the biggest drug traffickers in the country, and many had been members of or close to the Medellin Cartel.

Your book tells the story of the paramilitaries through three people – the activist Jesus Maria Valle, who was later killed, the lawyer Ivan Velasquez, and the journalist Ricardo Calderon. Why these three?

Because I could tell the story of the rise of the paramilitaries and how they made their way into high levels of the government through them. The three of them together ended up exposing the links between the paramilitaries and the government.

I had gotten to know Velasquez pretty well working in Colombia. While I was investigating Colombia, he was a Supreme Court assistant justice investigating Congress. He became a target of a smear campaign by then-President Alvaro Uribe—most of the congresspersons under investigation belonged to his coalition, and one was his cousin—and was falsely accused of trying to frame the president for murder. It turned out that the paramilitaries had gone to the presidential palace to plot against Velasquez and that Colombia’s intelligence service was spying on him.

Valle was an activist from the state of Antioquia, where Medellin is located, and a friend of Velasquez, who at the time was Antioquia’s chief prosecutor. Valle was this incredibly brave man who spoke out about paramilitary abuses. He knew he was going to be killed, people were begging him to flee, but he felt he had to protect his people. And no one else dared to say what he did at the time – that the military and, in his view, the Antioquia governor’s office were either complicit with these crimes, or looking the other way.

Then I chose Calderon, because as a journalist he reported on the smear campaigns against Velasquez. He’s an incredible powerhouse who’s deeply driven to tell the truth about what’s going on.

Throughout the book, you keep coming back to a massacre in the remote village of El Aro. Why?

It happened in October of 1998, after Valle had been warning authorities for months about the paramilitaries entering his home region of Ituango, the part of Antioquia where El Aro was located. In the days before the massacre, people from El Aro reached out to Valle to for help. Valle called the military, the police and the governor’s office, but no one helped.

The paramilitaries go into the town, kill 17 people including a young boy, rape women, then loot and burn the town down. They steal thousands of heads of cattle and drive them many miles for all to see. The paramilitaries are there for days, and no security forces come in to stop it. Witnesses in El Aro even see a helicopter owned by the military flying overhead. So El Aro became a powerful example of how paramilitaries were operating with, at a minimum, tacit acceptance by parts of the security forces.

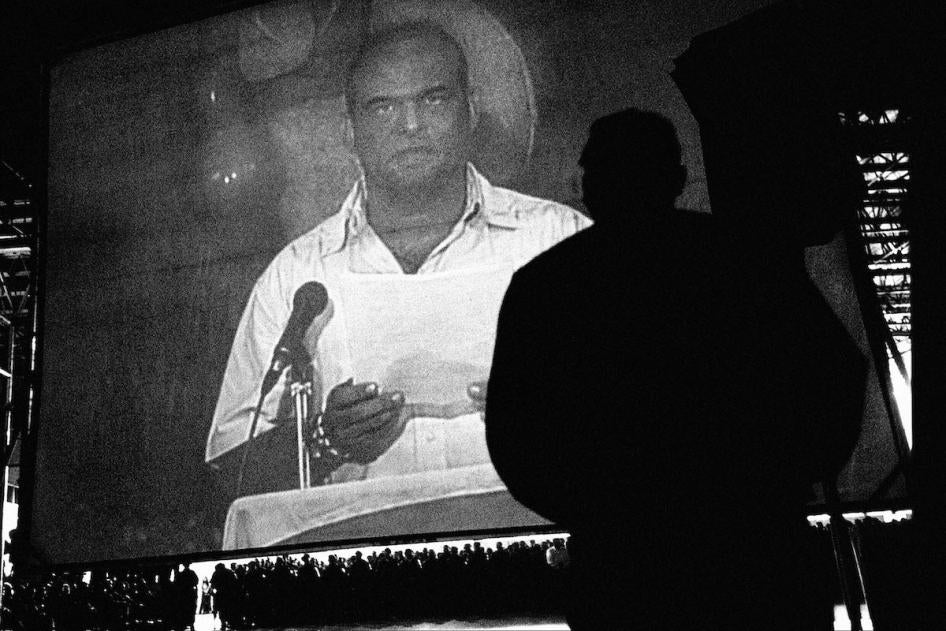

During Velasquez’s investigation of Congress, it becomes clear that people very close to Uribe – his chief of staff, his brother, a cousin – have links to the paramilitaries. Yet he is extremely popular. How is that?

I’m Peruvian, and grew up during the presidency of Alberto Fujimori, who became an incredibly corrupt autocrat, and was eventually convicted of crimes against humanity. Yet I supported him in the beginning because I thought he was bringing order in a time of chaos. At the time, the Shining Path guerrillas were doing terrible things in Peru’s countryside and were bombing the city I lived in. I was initially relieved, at age 18, that we seemed to be safer. I wasn’t paying attention to the bad things, though a few years later I changed my mind completely, and eventually became involved in building a case for his extradition from Chile to face trial in Peru.

People in Colombia were living with so much fear. And Uribe was very polished, seemed very committed and hard-working and seemed to produce results. He had policies that reduced kidnappings by the FARC and made it possible for Colombians to travel between cities by car again. People appreciated that and it made them more willing to look away from other issues.

What do you think of Uribe?

I don’t think you can conclusively say anything about him being responsible for the paramilitaries’ crimes. But the fact that he operated so closely with many people who have since been convicted of colluding with paramilitaries raises real questions about him. It means he either has a terrible lack of judgment and is blind to what’s going on around him, which just doesn’t fit with his image of total control, or he did know about a lot of it and chose to let it go forward. You can’t pretend that he is this powerful all-knowing person and somehow missed this.

How exactly were members of Colombia’s Congress linked to the paramilitaries?

About 30 percent were investigated, charged with or convicted of collaborating with paramilitaries, usually to commit electoral fraud, and in at least one case, murder.

The paramilitaries committed crimes in plain view, but people chose not to see them. Why is this?

I think a lot of Colombians were exhausted by the FARC’s violence. There was a willingness to look away from the paramilitaries’ atrocities, or to accept the arguments that the dead must have been guerrillas. So when Valle talked about paramilitaries colluding with the army, it was easy for people to dismiss him.

I think many Colombians deep down knew the collusion was happening and knew it was terrible.

Did you interview people close to Uribe?

I did. Some of them didn’t want to be mentioned. I spent four hours straight with one of his closest advisers, and I interviewed people who worked with him at different times, from people he worked with when he was governor of Antioquia to people in his presidential administration. I tried several times to interview him, and sent him a detailed questionnaire, but I never got anywhere.

I did meet Uribe while working at Human Rights Watch. It was 2004 and my first trip to Colombia. The director of the Americas division, Jose Miguel Vivanco, the then-Deputy Americas Director Joanne Mariner, and I met with Uribe. Jose Miguel criticized a new bill, supposedly meant to demobilize the paramilitaries but that in effect let members walk away virtually unpunished. Uribe got very angry and started marching around with his finger in the air saying how could we question him when he had done so much to bring security to the country, and basically lectured us for 30 minutes before storming off. After a while Uribe came back and he was much calmer and we talked about the issues.

The paramilitaries were never properly disarmed and now there are paramilitary successor groups in Colombia. Yet your book ends on a hopeful note.

Given the war on drugs in Colombia and the US—that is, the criminalization of drugs—you’re going to continue having this massive illicit market in drugs that gives organized crime enormous profits and the power to corrupt and infiltrate state institutions. And even though Colombia has a peace deal with the FARC, other criminal organizations will probably form as they leave the battlefield. The paramilitary successor groups and other criminal organizations are there. And they will continue fighting and people will keep dying. When there’s such financial incentive, whoever leaves that space, someone else is going to step in.

But I also think that some things have changed. Velasquez and Calderon and ultimately Valle did expose important truths, and Colombians have had to accept them to some extent. And that should be a source of hope to people in Colombia and beyond—that ordinary people, journalists, activists, lawyers, can make change happen.

*This has interview has been condensed and edited.