Some China-watchers will no doubt focus this week on the 19th Communist Party Congress, slated to open in Beijing on Wednesday. But other eyes—and hearts and minds—will be trained on a very different China celebration the very next day in Washington.

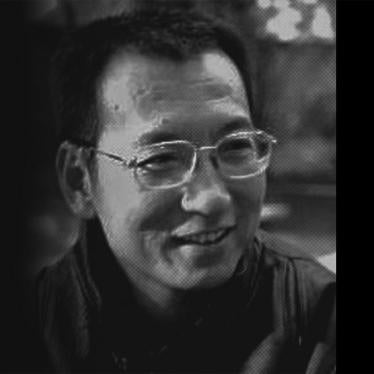

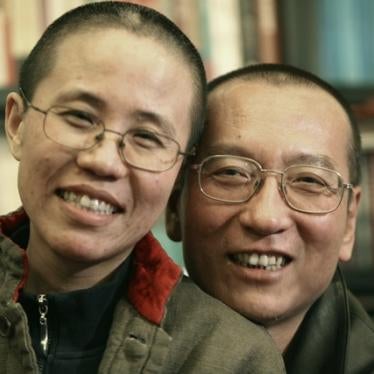

On October 19, Liu Xiaobo, the pro-democracy activist, outspoken dissident, and 2010 Nobel Peace Prize winner, who died in custody on July 13, will be remembered at the Washington National Cathedral—a place known for hosting progressive voices like Archbishop Desmond Tutu, and for holding memorial services or funerals for more than a dozen United States presidents. The gathering will both honor Liu Xiaobo’s legacy and renew a call for Liu’s widow, Liu Xia, to be freed. (Human Rights Watch is one of the Cathedral event’s organizers.)

Chinese authorities forcibly disappeared Liu Xia shortly after funeral proceedings in northeastern China for Liu Xiaobo. She was not seen again until August 19, when she appeared in a brief and seemingly coerced video released on social media, and has not been publicly heard from since.

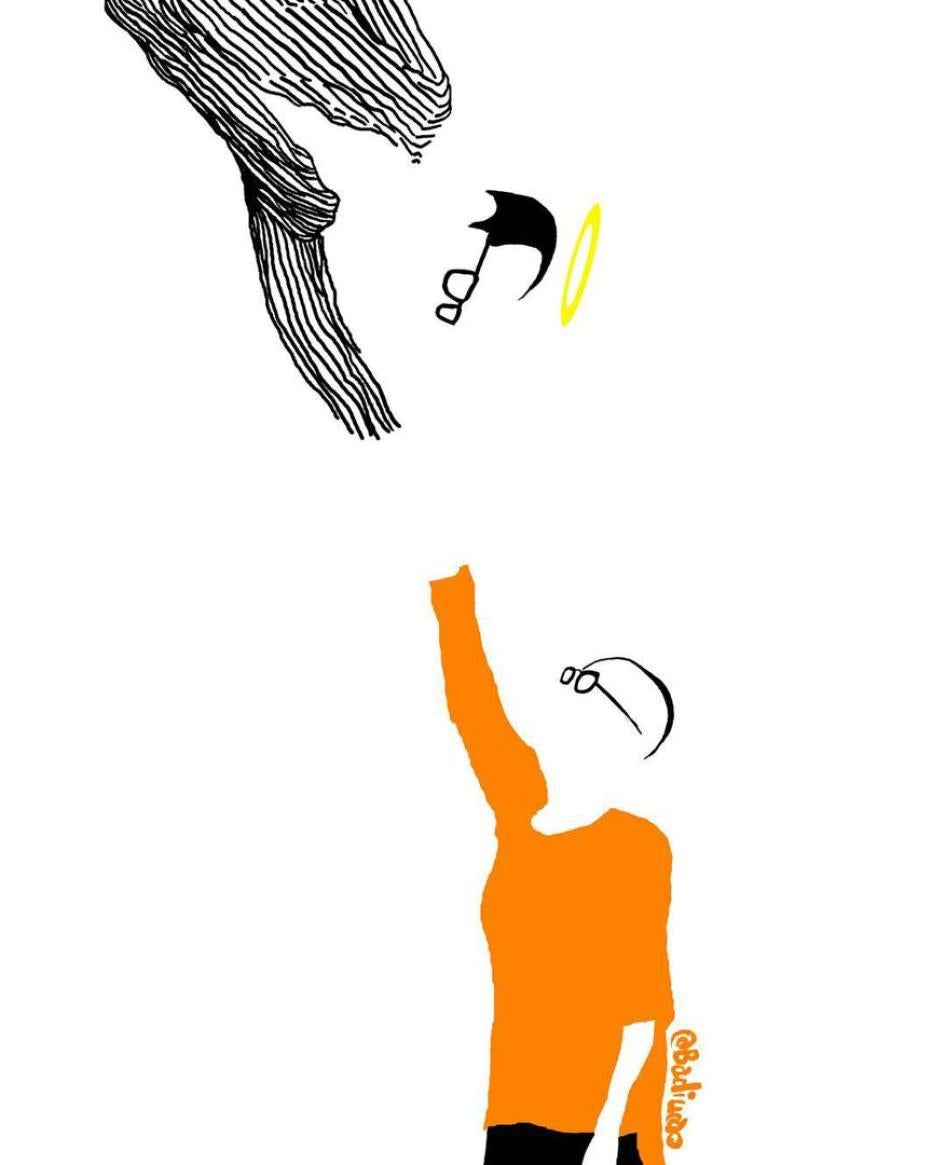

But around the world, people who can exercise their rights to peaceful expression are campaigning to remember and seek justice for Liu Xiaobo and Liu Xia. Artists, including Australia-based Badiucao and Berlin-based Ai Weiwei, have produced works featuring Liu Xiaobo’s and Liu Xia’s images. Members of the United States Congress have nominated Liu Xiaobo to posthumously receive the Congressional Gold Medal. Journalists, activists, and writers continue to campaign for the pair, and Norwegian Nobel Committee chair Berit Reiss-Andersen will read from Liu’s essay, “I Have No Enemies,” at the Cathedral. More can be expected to join this global chorus.

Meanwhile in Beijing, President Xi Jinping is expected to award himself another five-year term at the party congress. There are no signs that his ferocious crackdown on human rights will abate in the foreseeable future. Xi had not yet assumed power when Liu was detained in December 2008 on baseless charges of inciting subversion that resulted in his conviction a year later. But Xi’s administration has racked up an appalling record of imprisoning peaceful critics. Some are known to have been denied access to adequate medical treatment, and several have died in detention or shortly after being released.

In Liu Xiaobo’s case, the Xi government took its brutality to breathtaking extremes. Liu, who died from complications of liver cancer two years short of completing an 11-year sentence, was denied access to most family and friends, and to the treatment of his choice. Chinese authorities, eager to paint themselves as having given him the best possible care, invited one American and one German oncologist to examine Liu. The doctors declared him well enough to travel abroad for treatment, but then Chinese state media broadcast an unauthorized video clip in which the foreign doctors appear to be endorsing their Chinese counterparts’ treatment of Liu, suggesting that the doctors’ visit was for the authorities little more than a propaganda exercise.

After Liu’s death on July 13, authorities orchestrated funeral rites over which Liu Xia appeared to have no control. Only a few of Liu Xiaobo’s relatives, and some unidentified individuals, possibly state security officials, were allowed to attend. Authorities also moved swiftly to detain anyone seen to be mourning Liu’s death, and forcibly disappeared Liu Xia.

It’s safe to predict that no one will press Xi about these developments at the Party Congress.

Back in Beijing, China’s leaders will work hard to project an impression of authority, competence, and control. But their appalling treatment of Liu Xiaobo and ongoing torment of Liu Xia reveal their deep insecurity about criticism of their rule and their political legitimacy—problems that can only be resolved by real respect for human rights.