UPDATE:

On September 19, Morocco’s Inter-Ministerial Delegation for Human Rights (Délégation Interministérielle des droits de l’Homme) responded to the September 5 Human Rights Watch report on evidence of police abuse against “Hirak” protesters in the Rif.

The Inter-Ministerial Delegation for Human Rights said in its response that all allegations of torture have been examined and the courts are handling these allegations. It also stated that in the course of responding to the Hirak protests, 589 police agents sustained injuries. Human Rights Watch is not in a position to confirm the number, nature, or severity of those injuries.

Human Rights Watch presented allegations by defense lawyers that police beat protesters upon arrest and in custody. Those allegations appeared to have been supported by medical exams conducted by forensic doctors whom the National Council for Human Rights had dispatched to visit the men in custody.

Human Rights Watch reviewed the transcript of the apparently unfair trial of 32 protesters in which the court convicted all 32 based on their “confessions” to the police, which all of the defendants repudiated before the prosecutor and trial judge. The vast majority said that the police had beat them and forced them to sign their statements without reading them.

The court denied a defense request for a forensic examination of the defendants, contending that such an examination would be unable to determine the cause of the injuries observable on the defendants’ bodies. However, the forensic exams commissioned independently of this trial by the National Human Rights Council on some of the defendants in this and other cases, showed that such examinations could provide strong indications about the credibility of the defendants’ allegations.

Under international law, even if some protesters engage in acts of violence, as Human Rights Watch’s report noted, police are not justified in using more force than is necessary to take a person into custody or in using violence against people who are already in custody and offering no resistance.

Human Rights Watch reviews responses to its findings and acknowledges and corrects errors on its correction page. However, the response from the Inter-Ministerial Delegation for Human Rights does not challenge any factual assertion made in that report. Any and all credible investigations into allegations of torture would be a positive step. Such investigations should include, where warranted, forensic examinations by properly trained and independent experts.

For more regarding Human Rights Watch’s report on the Rif, see here.

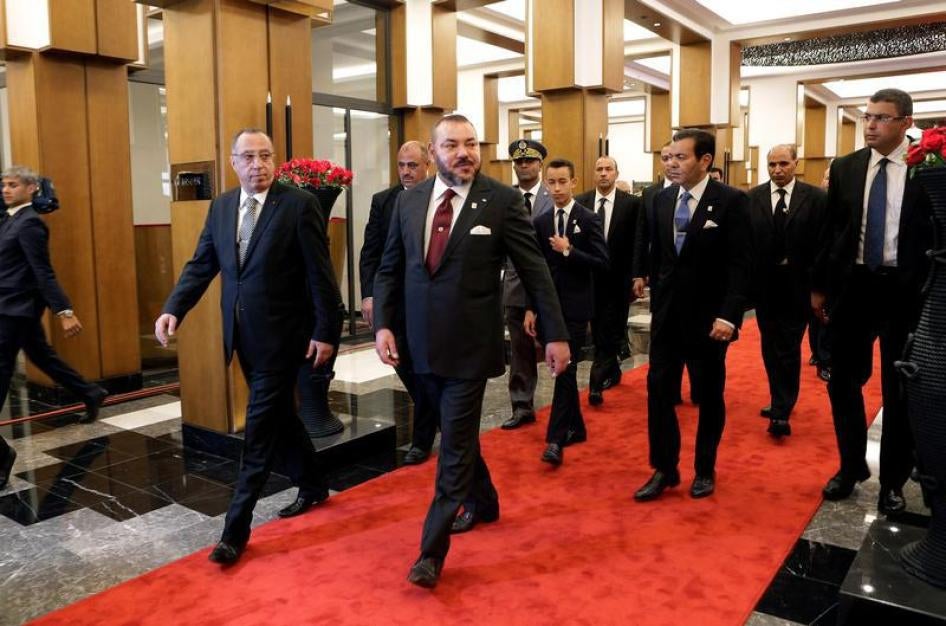

(Tunis) – King Mohammed VI should press for effective investigations into allegations that

Morocco’s police forces tortured people suspected of participating in the 2017 “Hirak” protests in the Rif region, Human Rights Watch said today. Instead, in a

televised address to the nation on Throne Day, July 30, the king appeared to whitewash the police’s handling of the unrest in Al Hoceima, the main Rif city, saying that security forces showed “restraint and commitment to the rule of law.”

The king’s comments ignored reports by forensic doctors who examined a group of detainees arrested around the Rif protests and found injuries they said corroborated the detainees’ accounts of police violence. The doctors, who examined the detainees at the request of the

National Human Rights Council (Conseil National des Droits de l’Homme, or CNDH), an independent state body, also noted that many detainees said the police forced them to sign written statements unread. Many are now serving prison terms, while others remain in pretrial detention.

“The king’s unconditional praise of the security forces despite the allegations against them will only encourage the belief that those who abuse detainees will never face any consequences,” said

Sarah Leah Whitson, Middle East and North Africa director at Human Rights Watch.

In his Throne Day speech, to date his only public comment on the Rif protests which began almost a year ago, the king chose to lambaste the public administration for its failure to implement development polices in the embattled region, while singling out the security forces for “bravely and patiently fulfilling their duty … as they maintained security and stability.”

The Hirak movement sprang from an incident in October 2016, in which a fishmonger was killed while trying to rescue his goods that authorities had just confiscated. Since then, the movement has staged several mass protests to end what they say is the government’s discrimination against the region with regard to economic and social development.

Authorities have tolerated many of the Hirak demonstrations, although they prohibited a major one planned for July 20 in Al Hoceima, and used teargas to disperse those who attempted to defy the ban. The demonstrations have been

peaceful, with some exceptions, mostly stone-throwing. There has been one death, of 25-year-old Imad Attabi of Al Hoceima, who was fatally wounded on July 20 in circumstances that authorities promised to investigate. The Moroccan Association for Human Rights, an independent group, said a teargas canister fired by the police hit him in the head, fatally wounding him.

In late May, after seven months of sporadic protests, authorities started cracking down and arresting protesters. According to well-informed sources, 216 protesters are behind bars, including 47 in Casablanca’s Oukacha prison awaiting trial and 169 in Al Hoceima’s regional prison, some sentenced and others awaiting trial or appeals.

On July 3, Moroccan media

published a leaked copy of medical reports that indicated severe police abuse of detained protesters. The National Human Rights Council, which had commissioned leading forensic doctors to prepare the reports, said that the reports had not been finalized and were thus unofficial. But the next day, Justice Minister Mohamed Aujjar

announced that he had ordered copies forwarded to prosecutors at the Al Hoceima and Casablanca courts trying these defendants “to include these reports in the case files … [and] take necessary legal measures.”

On June 14, a first instance court in Al Hoceima convicted all 32 defendants in a mass trial of Rif protesters, including 11 of the men the forensic doctors examined. The charges included insulting and physically assaulting members of the security forces, armed rebellion, and destruction of public goods (articles 263, 267, 300 to 303, and 595 of Morocco’s

penal code). The court imposed 18-month prison terms on 25 and suspended sentences for the others. Human Rights Watch has reviewed the court’s written judgment. An appeals court on July 18, after the doctors’ reports were available,

upheld the convictions but shortened the sentences; its written judgment is not yet available.

On July 29, the eve of Throne Day, King Mohammed VI

pardoned 1,178 prisoners, including 42 members of the Hirak movement, but they did not include the group sentenced by the Al Hoceima Court or those the forensic doctors had examined.

Morocco’s 2011 constitution includes a prohibition on abusive force: “No person, whether a private citizen or public agent may, under any circumstances, harm the physical or moral integrity of anyone else… The practice of torture, by any person and in whatever form, is a crime punished by the law.”

Under Morocco’s code of penal procedure, no statement prepared by the police may be admitted into evidence if it is obtained through coercion or violence. In practice, however, courts

routinely admit into evidence contested “confessions” and base convictions on them, without opening investigations into allegations of

torture and other physical mistreatment. This approach of ignoring allegations of torture and other abuses by the police can only be reinforced by the king’s support of the police handling of the Rif protests despite the lack of investigations into such allegations there, Human Rights Watch said.

“King Mohammed VI said on Throne Day that Moroccans ‘have every right and ought, in fact, to be proud of their law-enforcement authorities,’” said Whitson. Wouldn’t they be even prouder if allegations of police abuse were met with credible investigations, and if the courts refused to convict on the basis of tainted confessions?”

The Court Judgment

Human Rights Watch examined the 62-page judgment in the trial of 32 suspected Hirak protesters before the Al Hoceima Court of First Instance, case 76-2103-2017, with Judge Mourad Abdessoulami presiding. The guilty verdicts against all 32 men, who were tried according to flagrant délit (“caught-in-the-act”) procedures, are based on the defendants’ “confessions” to the police, which they all repudiated before the prosecutor and trial judge. The court, which announced its verdict on June 14, 2017, dismissed all claims by the defendants that the police had coerced the majority of them to sign their statements without reading them.

The judgment says that 23 defendants told the prosecutor, and later the trial judge, that police beat them during their arrest or at Al Hoceima’s main police station, or both. The defense team requested that the prosecutor, who, according to the judgment, observed signs of violence on 10 of the detainees, order a medical examination. The prosecutor complied, but the examinations focused on providing care for the men rather than determining whether their physical condition could be consistent with their allegations of mistreatment, two defense lawyers told the court and confirmed later to Human Rights Watch.

The lawyers then requested that the court order a proper forensic medical examination of the detainees who complained of police abuse. The judge denied the request on the grounds that a court “does not order an expert analysis unless it expects to rely on that analysis to help it form its intimate conviction as to whether to convict or acquit.” The judgment continues, “the motive behind requesting an expert analysis in this case is to impose responsibility on a party for the alleged torture and coercion. Therefore, fulfilling the request would cause the court to lose its neutrality, turning it into a prosecutorial rather than adjudicatory body, which would be contrary to the law.”

The court also contended that a medical examination to determine the cause of the injuries that the prosecutor observed would be inconclusive because any number of incidents could have caused them, such as bodily contact with fellow protesters as they attempted to escape, or with police forces as they resisted arrest, or stones thrown by fellow protesters.

The court’s refusal to order forensic medical examinations of defendants who made torture allegations seems incompatible with Morocco’s obligations under the

Convention against Torture, and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment. The medical report commissioned independently of the trial by the National Human Rights Council and prepared by two high-level forensic doctors (see below for details) showed that such examinations could provide strong indications about the credibility of the defendants’ allegations.

The statements attributed by the police to the 32 defendants included confessions that they had thrown stones and bricks at police forces on May 26, to prevent them from arresting the Hirak leader Nasser Zefzafi, while he was addressing protesters from the rooftop of his parents’ house in Al Hoceima. In a

video of that speech, Zefzafi repeatedly asks protesters to remain nonviolent using the Arabic word

silmya, which means peaceful. According to the written minutes of at least 18 of the defendants’ statements to the police,

silmya was in fact a code word, previously agreed on by Zefzafi and his supporters, indicating an order to attack the police violently. All the defendants interrogated by the judge about this allegation strongly denied the existence of any code word, and stressed that

silmya had no meaning other than peaceful.

All 32 men repudiated their police statements both before the prosecutor and the trial judge, denying that they had stoned or used other forms of violence against police forces. At least 25 said they were not allowed to read the minutes of their statements to the police before being pressured to sign them under threat, including in some cases, of sexual violence. Many said they were threatened with “transfer to Casablanca,” with the implication that there they would face graver charges, including terrorism and harming the state’s internal security, a crime punishable by death. While a few defendants refused to sign their statements, the vast majority did.

The defense team asked the court to invalidate the statements on the grounds that they had been coerced. The court rejected the request, reasoning that the threat to transfer suspects to another city was not a credible one since it was not the police’s prerogative to do so. The court also stated that the fact that some detainees refused to sign their statements despite their claims of being pressured to sign was a basis to dismiss all coercion claims.

The first instance court sentenced 25 of the 32 defendants to 18 months in prison on charges of “armed rebellion” and attacking police forces. The other seven received suspended prison sentences between two and six months, and a fine.

The first instance court issued its verdict in this case before the National Human Rights Council-mandated doctors had completed their draft reports indicating that some of the defendants had been physically abused. Those reports, however, were available to the Al Hoceima Appeals Court when it opened its appeals trial of the defendants. Minister of Justice Mohamed Aujjar had ordered on July 4 that those medical reports be submitted to the courts, and the appeals judge had agreed to admit those reports into evidence, a defense lawyer, Abdel Majid Azaryah, told Human Rights Watch.

Nevertheless, on July 18, the appeals court upheld the convictions but reduced the sentences of the 25 who had 18-month sentences to 7 months. Because the written verdict is not yet available, it is not possible to know the appeals court’s reasoning for convicting the defendants, or how it weighed the medical reports of the National Human Rights Council, which suggested physical abuse by police and allegations that the confessions were coerced.

The Medical Reports

The National Human Rights Council (CNDH) has criticized the state of forensic medicine in Moroccan courts, commenting in a 2013

report that when it came to court-ordered examinations of defendants, “these are usually assigned to medical practitioners included on the lists of the court of appeal experts; most of whom have no prior training in the examination and assessment of physical injury.” The CNDH added, “Reporting duties are not standardized by the courts. Experts’ practices are also uneven, both in terms of procedures and report drafting. The report rarely includes a discussion of the expert’s findings, and the injuries are often described in a peremptory manner.” As of this writing, government ministries have drafted a law on forensic medicine that, among other things, would oblige doctors who forensically examine defendants who allege torture or mistreatment adhere to international standards for such examinations. Parliament has not yet taken up the draft law.

In the case of arrested Rif protesters, the CNDH appointed two forensic experts who were granted access to examine groups of detainees, to prepare reports for the CNDH on their allegations of police torture and mistreatment. Dr. Hicham Benyaïch, head of the forensic medicine institute at Casablanca’s Ibn Rochd Hospital, and Dr. Abdallah Dami, a member of that institute and vice-president of the Moroccan Association of Forensic Medicine, conducted one-on-one physical examinations between June 14 and 18 of 34 men arrested in late May or early June. Fifteen were being held in Al Hoceima’s regional prison, one was provisionally free in Al Hoceima, and 19 had were in pretrial detention in Oukacha Prison in Casablanca, after having been interrogated at the headquarters of the National Brigade of the Judiciary Police.

Twenty-five of the 34 detainees told the doctors that the police who arrested them beat them, severely in some cases, slapping and punching them in the face, kicking them, and clubbing them with batons, police helmets, walkie-talkies, and a stapler, both on the head and on other parts of the body. At least two prisoners said police officers put filthy mops on their mouths. One said a police officer pulled hair from his beard and threatened to burn his beard by flicking a cigarette lighter close by. The doctor who examined him said irritation marks on his chin corroborated his account.

Many of the prisoners said some police officers covered the lenses of video surveillance cameras in Al Hoceima’s police station before beating them or fellow detainees. One prisoner said officers took him to the bathroom, took his shirt off and tied his feet with it, and beat him on the soles of his feet. Nearly all of them said the officers taunted them with vulgar insults directed at them and their relatives. Another prisoner told the judge during his trial that a police officer took out a knife and threatened him with it.

According to the council’s reports and also the Court judgment, at least 16 detainees identified a particular police officer in Al Hoceima by his first name, as responsible for violent beatings and repeated insults and threats, including threats to rape or sexually assault the detainees and their female relatives. One of the doctors recommended to “urgently and thoroughly investigate the actions of the police commissioner” that they named, due to the accumulation of accusations against him. It is not known whether judicial authorities have opened an investigation into these allegations.

Among the conclusions one of the doctors reached in their reports:

The testimonies received from those arrested about the use of torture and other ill-treatment during their arrest and detention in the premises of the Al Hoceima police station are as a whole credible by virtue of their consistency and coherence, and the existence of physical and psychological symptoms and sometimes physical traces highly compatible with the alleged abuse.… The accounts provide a pattern of reported events which, if confirmed, involve a range of acts constituting acts of torture and other ill-treatment and violations of the constitutional and legislative guarantees that should be enjoyed by any person arrested or detained.

Both doctors called on judicial authorities to investigate these allegations, and recommended medical and psychological care for many of the detainees they examined.

Legal Requirements

The Convention Against Torture requires states to “ensure that its competent authorities proceed to a prompt and impartial investigation, wherever there is reasonable ground to believe that an act of torture has been committed in any territory under its jurisdiction, … that any individual who alleges he has been subjected to torture in any territory under its jurisdiction has the right to complain to, and to have his case promptly and impartially examined by, its competent authorities, … [and] that any statement which is established to have been made as a result of torture shall not be invoked as evidence in any proceedings, except against a person accused of torture as evidence that the statement was made.”

Morocco’s penal code, as amended in 2006, penalizes the act of torture, defined as, “any act, committed intentionally by a public official or someone acting at his behest or with his express or tacit consent, by which acute physical or mental pain is inflicted on a person in order to intimidate him or her, or to pressure that person, or someone else, to obtain information or indications, or confessions; to punish that person for an act that he or she, or a third person has committed or is suspected to have committed, or when such pain or suffering is inflicted for any other reason based on any type of discrimination.” (article 231.1)

The Principles and Guidelines on the Right to a Fair Trial and Legal Assistance in Africa, drawn up by the African Commission on Human and Peoples Rights, state that, “Any confession or other evidence obtained by any form of coercion or force may not be admitted as evidence or considered as probative of any fact at trial or in sentencing. Any confession or admission obtained during incommunicado detention shall be considered to have been obtained by coercion.” The principles also state that, “When prosecutors come into possession of evidence against suspects that they know or believe on reasonable grounds was obtained through recourse to unlawful methods, which constitute a grave violation of the suspect’s human rights, especially involving torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, or other abuses of human rights, they shall refuse to use such evidence against anyone other than those who used such methods, or inform the judicial body accordingly, and shall take all necessary steps to ensure that those responsible for using such methods are brought to justice.” Morocco joined the African Union in January 2017.

Morocco’s Code of Criminal Procedure obliges the prosecutor, with narrow exceptions, to order a medical examination if he or she observes signs of violence on the suspect. If the suspect complains of police violence or requests a medical examination, the prosecutor must order an exam before he or she commences questioning the suspect. The code imposes a similar requirement on investigating judges, but not on trial judges. However, the code’s requirement to exclude from evidence any statement obtained through the use of “violence or coercion” imposes an obligation on trial judges to ensure that any statement was obtained voluntarily before using it as incriminating evidence.

Article 290 of the code, however, undermines the obligation to exclude coerced evidence, providing that for offenses occasioning punishments of five years or less of prison time, statements prepared by the police are to be deemed trustworthy unless the opposite is proven, thereby imposing the burden on the defendant to prove that his “confession” to the police was false. The written judgment of the first instance trial of 32 Hirak detainees cites article 290 as a reason to dismiss the defendants’ allegations, arguing that statements to the police can be invalidated only by producing “highly probative evidence such as the testimony of a witness or an expert’s analysis, or something comparable in the form of legally valid documents – but mere allegations without proofs cannot be considered a counterproof.”