(Vienna) – The government of Turkmenistan has forcibly evicted homeowners in Ashgabat and demolished their homes without adequate compensation in preparation for the Asian Indoor and Martial Arts Games, the Turkmen Initiative for Human Rights (TIHR) and Human Rights Watch said today. To standardize the city’s appearance, authorities have also systematically demolished extensions and additions homeowners have made to their properties, without allowing them to appeal the demolition decisions to a court.

The 5th Asian Indoor and Martial Arts Games (AIMAG), are scheduled to take place in Ashgabat, Turkmenistan’s capital, from September 17 to 27, 2017. An estimated 8,000 athletes from dozens of countries are expected to participate.

“Thousands of people have been deprived of their property or left in squalid housing, in order to transform Ashgabat into a white marble city and to prepare for the games,” said Farid Tuhbatillin, TIHR’s executive director. “The games will last all of 10 days, but people left with inadequate or no housing will suffer for years to come unless they are properly compensated.”

The Turkmen government should ensure that Ashgabat homeowners and residents who have been forcibly evicted get fair and adequate compensation for the loss of their property and costs incurred due to the forced evictions, TIHR and Human Rights Watch said. Turkmen authorities should immediately take steps to provide Ashgabat residents who were denied compensation, or who were left homeless because of the city’s infrastructure and beautification projects, access to an effective judicial mechanism capable of promptly and fairly awarding them their compensation and any other appropriate remedy.

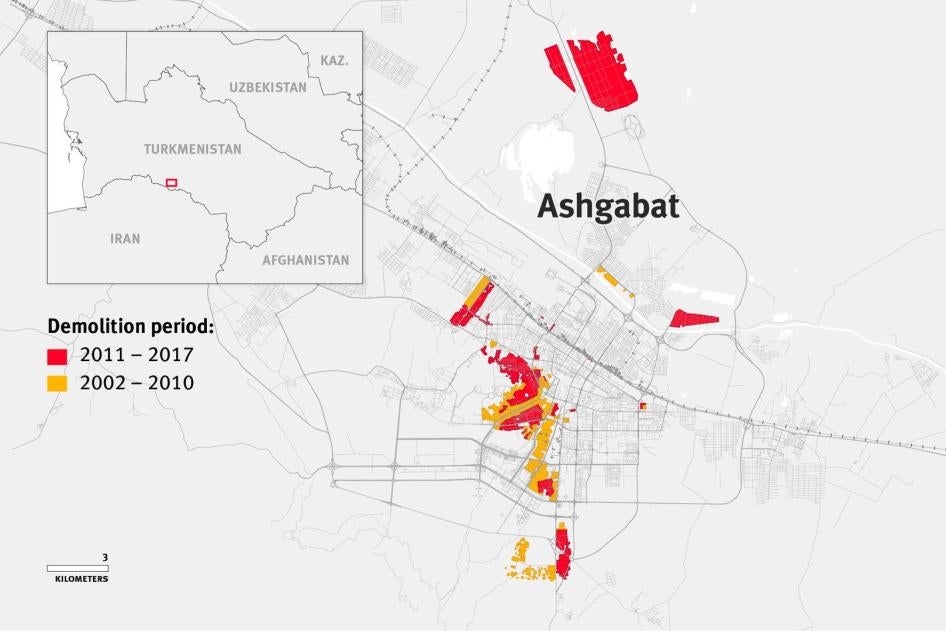

Expropriation, evictions, and house demolitions carried out in preparation for wide-scale urban renewal and beautification have been taking place throughout Ashgabat over the course of almost two decades, in a way that grossly violates the right to private property and adequate housing, the organizations said. But the scale and pace of demolitions and violations of property and housing rights have intensified over the last five years, as authorities have geared up for the games.

Turkmenistan is one of the most closed countries in the world, and the games are a rare opportunity to put Turkmenistan’s human rights record under the international spotlight.

Presidential decrees have described demolitions and Ashbagat’s reconstruction for the games as “creat[ing] the most favorable conditions for the cultural leisure of the people and visitors to Ashgabat in the era of power and happiness.”

Ashgabat homeowners are entitled to either an alternative “equivalent” living space or financial compensation for expropriated homes, but in fact in many cases TIHR and Human Rights Watch documented, the “compensation apartments” were worth significantly less than the total worth of their property, or were too small for the family’s needs.

In many cases the authorities provided entire households – some with as many as 10 to 15 people – with just two- or three-room apartments. In other cases, authorities evicted homeowners before their compensation apartments were fully constructed, forcing residents to pay for a place to live until they were ready. In other cases, conditions in compensation apartments were poor, in buildings with leaks, non-functioning elevators, and other problems.

Authorities also forced homeowners to accept “upgraded” apartments in exchange for their demolished homes, but demanded that families pay the difference beyond the assessed worth – in one case the equivalent of US$25,000 – and denied them the title to the new property until they paid.

Ashgabat residents who tried to contest the expropriation of their homes or seek better compensation were denied justice, threatened with homelessness, and in some cases, harassed or threatened by the authorities.

The evictions of Ashgabat residents and the destruction of their homes has violated Turkmenistan’s obligations under the right to housing as set out in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), which Turkmenistan ratified in 1997.

Turkmenistan: Gazha District Satellite Imagery

People evicted from their homes are entitled to various protections, including: genuine consultation with the authorities; adequate and reasonable notice; information on the eviction and future use of the land; adequate compensation or alternative housing; legal remedies; and legal aid. International law prohibits “forced evictions,” defined as the permanent or temporary removal of individuals, families, or communities against their will from their homes or land, without access to appropriate forms of legal or other protection.

“The authorities are trying to boost Turkmenistan’s international prestige by hosting the AIMAG,” said Rachel Denber, deputy Europe and Central Asia director at Human Rights Watch. “But no one will be impressed by how monstrously they are cheating residents out of their homes and bullying homeowners.”

For additional details and examples of the treatment of evicted families, please see below.

A Climate of Severe Repression

The Turkmen government tightly controls all aspects of public life and systematically denies freedoms of association, expression, and religion. The country is utterly closed to all independent scrutiny. The authorities threaten, harass, or imprison people who question government policies, however modestly. The Turkmen government does not tolerate independent civic activism. The few people who do human rights work do so under the radar and at great personal risk.

It is in this climate of severe repression that the Turkmenistan Initiative for Human Rights (TIHR) and Human Rights Watch collected information about dozens of cases for this report. All of the cases of forced evictions and demolitions took place in the past four years, with most dating from 2015 and 2016. Human Rights Watch and TIHR interviewed Turkmen activists and lawyers who follow these developments closely, and reviewed letters to high-level government officials asking them to intercede on their housing cases. We also reviewed relevant national and international laws, and Human Rights Watch and TIHR sent a letter to the government of Turkmenistan, seeking its views on the findings, but has not received a response.

Full Demolitions

Inadequate Compensation

Turkmenistan’s Property Law stipulates in article 29 that the government may expropriate only “in cases prescribed by law, and in which the owner is provided equal property or compensation in full for the losses caused by the expropriation.” Turkmenistan’s 2013 Housing Code stipulates in article 27 that when the state seizes residential property for public needs, “the owner, family members living with him, and any other persons permanently residing [there] will receive an equivalent alternative residence” or “compensation in the amount of the value of the demolished dwelling, its auxiliary buildings, other structures and gardens.”

However, the groups are aware of no cases in the past five years in which homeowners were offered this choice. Moreover, in numerous cases in which property was offered as compensation, authorities did not appear to provide “equivalent, well-maintained housing” in exchange for seized property. Instead, the City Housing Fund based its compensation calculation on incomplete information, using only the square meterage of the formally registered property, and only the number of family members who originally had residence permits [propiska] for that property, rather than updated information about the actual family size, home size, land, and property affected by the expropriations.

The authorities provided households – some with as many as 10 to 15 people – with just two- or three-room apartments, even though article 70, point 3 of the Housing Code sets 12 square meters as the minimum living space per person.

For example, in a January 2017 letter to Turkmenistan’s president, the Galkovski family detailed how earlier that month local municipal authorities provided their family of 10, evicted from a four-room apartment, just a two-room apartment in compensation. The family refused to sign an agreement to move. In response, the local authorities filed suit against them. The court ruled for the authorities.

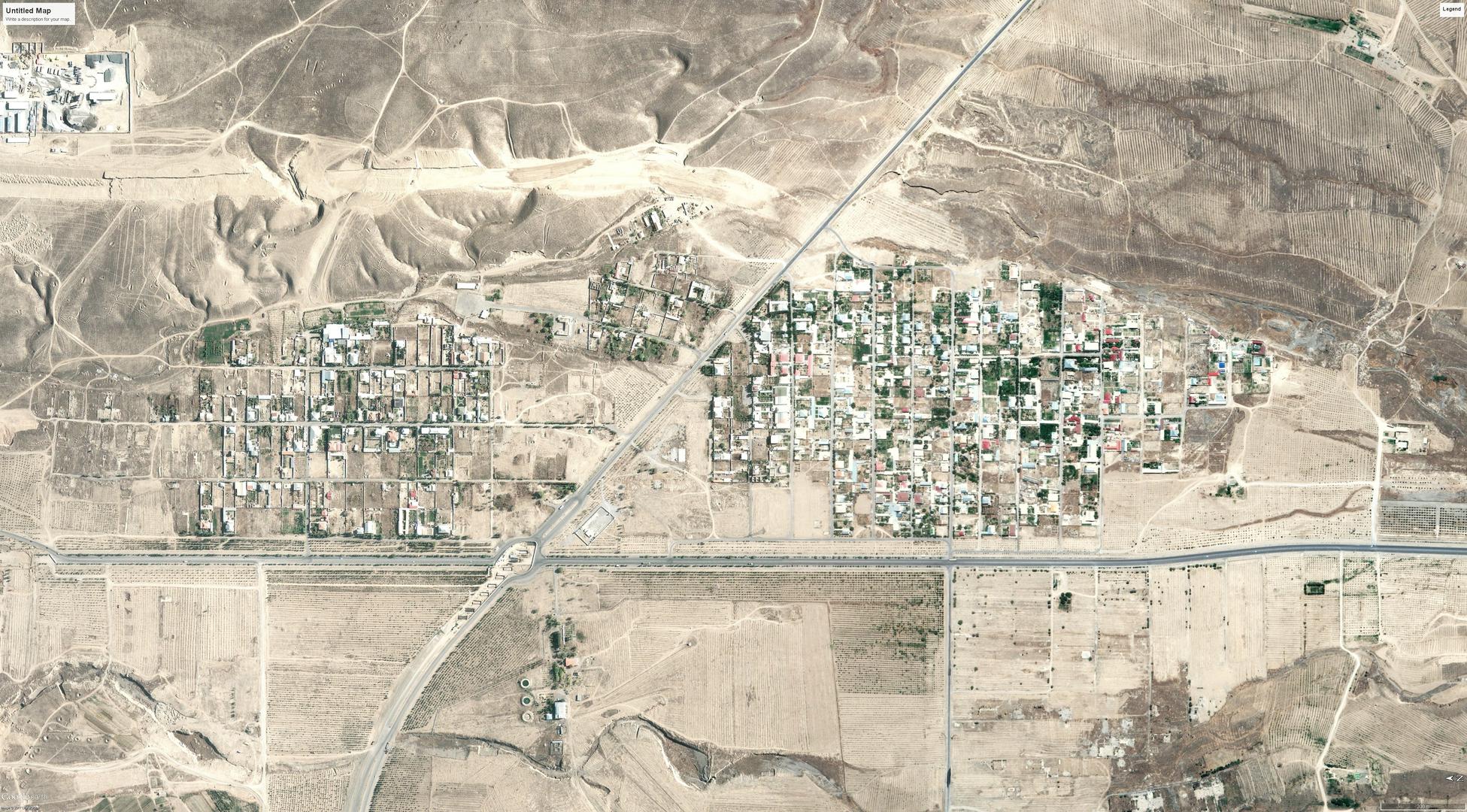

Turkmenistan: Gazha-south Satellite Imagery

In many of the cases, expropriated homes consisted of a house on a plot of land or an apartment on the first or second story, and outbuildings or additional structures that the family built over time, as their children grew up and had families of their own. These outbuildings – which variously included summer kitchens, bathrooms, saunas, extra bedrooms, and even small cottages – became integral to households. While article 27 of the Housing Code does not envisage including the size of outbuildings in making calculations for compensation, it does envisage including their value, if the homeowner chooses monetary compensation rather than an apartment. But the authorities did not give homeowners a choice.

In one example, an older couple, their adult daughter, and her 16-year old child lived in a private house with an outbuilding in the Ashgabat neighborhood of Gazha until mid-2016. The grandparents occupied the main house, while the mother and her child lived in the outbuilding. In compensation for their expropriated property, authorities did not count the outbuilding and provided only a two-room apartment.

In another example from 2016, authorities compensated a household of 17 people with a two-room apartment for their expropriated property in the Gazha neighborhood. The household included four family units who lived jointly in a main house with three small bungalows and other outbuildings. In calculating compensation, authorities apparently counted only the size of the main house. To justify excluding the three bungalows, the authorities apparently claimed to possess a decree excluding houses built after 1985 from compensation, but declined to give the family a copy.

Since many of the outbuildings had stood on properties for a decade or more, it seems unlikely that municipal authorities had been unaware of their existence. Moreover, it appears that the city authorities had no objections to the outbuildings when homeowners were using them. Several informed sources described the longstanding practice of local officials demanding bribes from homeowners who wanted to build outbuildings.

One household of three family units comprising 15 people was denied adequate compensation after the home they owned in Gazha was demolished in 2015. Their property consisted of a main house, an adjacent summer house, kitchen, and sauna, which they had built over the previous 20 years as their family expanded. The family had tried to register the outbuildings with the Ashgabat Bureau of Technical Inventory, but it had allegedly refused.

In calculating the family’s compensation, the City Housing Fund considered only the size of the main house and offered the household a three-room apartment. When the family tried to explain that it was not enough space for their family, officials told them they could go to court to divide the property they got in compensation. The family filed a complaint with the prosecutor’s office, but the office replied that the family had legal documents only for the main house and that the alternative housing provided was adequate.

The demolition of the family’s house and outbuildings left them “very frustrated, because they had lost property and everything that had been built in the yard – they had trees, a garden,” said someone knowledgeable about the case. The family was also worried that they would have to borrow money from friends to buy an apartment for one of the sons.

Loss of Property Title

Human Rights Watch and TIHR documented several cases in which the only option the authorities provided families whose homes had been expropriated was an apartment that far exceeded the size of the expropriated property the City Housing Fund calculated for compensation. Representatives of the fund demanded that homeowners pay the difference, which in in at least one case of which the groups are aware, amounted to the equivalent of US$25,000.

Yet Turkmenistan’s current economic climate and the lack of a state program to provide affordable loans or mortgages left families without meaningful options. They had to either agree to this arrangement or be left homeless.

Following complaints that some homeowners filed with the prosecutor’s office, the municipal authorities allowed the families to move into the new dwellings, but would not hand over ownership documents until the families paid the full difference. In most cases the groups reviewed, families were given one year and, in one case, six months, to pay off the sum.

Compensating families by obliging them to pay for the housing provided as compensation effectively resulted in families losing the title to their property.

In one case, two families, 10 people in all, had been living in Gazha until mid-2016, when their properties were expropriated. They were each given an apartment of greater value than their expropriated property. The City Housing Fund told both families that until they paid the difference, they would not be able to register their new apartments or get the titles.

In an open letter to the president dated June 28, 2016, Viktoriya Melikhova said that instead of providing her and her sister adequate accommodation for their two families, a total of seven people who had lived in a home on Archmanskaya Street in Ashgabat, city authorities at first offered them a three-room apartment, which was not enough space for their families. Then they offered a four-room apartment, demanding additional payment. Melikhova wrote: “We requested two separate two-room apartments but we were informed that we can have a 4-room apartment with an extra payment of $14,000, which needed to be paid within six months.”

Melikhova and her family did not have the money. They had no choice but to take the smaller apartment, eventually forcing Melikhova, her husband, and son, to live with relatives. City officials also registered the property in the name of the husbands, even though the expropriated property belonged to the sisters.

TIHR and Human Rights Watch have information about nine other families, who in 2015 claimed that the replacement apartments the municipal authorities provided were larger than the property seized for demolition, and that they were required to pay the difference. Although the amount varied from family to family, none of the families could afford the difference.

Compensation Denied

Human Rights Watch and TIHR also received information about several cases in 2015 in which the authorities denied any compensation whatsoever to homeowners. In these cases, there was no dispute over the fact homeowners had occupied their homes for many years, but authorities claimed they were unable to produce valid ownership and other technical documents, ranging from building permits to valid stamps in the title document.

Turkmenistan: Shor Dacha Satellite Imagery

Poor Apartment Conditions

The 2013 Turkmen housing code clearly stipulates in article 27 that residents whose properties are expropriated for state use “shall receive in exchange an equivalent well-equipped [emphasis added] alternative living space.” Yet TIHR and Human Rights Watch documented several cases in which compensation apartments fell dramatically short of these standards.

Elena Belousova lived in a two-room apartment with her husband in Ashgabat until December 2016, when the couple was evicted and their apartment expropriated for demolition. City authorities granted Belousova a one-room apartment in a building that had not yet been completed. They refused to let her see it before making her sign an agreement to move, threatening that if she refused to sign, she would be left homeless.

The compensation apartment was 13 square meters smaller than Belousova’s expropriated apartment. In calculating compensation based on the number of people in the household, the City Housing Fund officials did not count Belousova’s husband of 17 years because he was not formally registered at that address. Compounding the failure to account for her husband as a member of the family, the elevator in the building did not work for five months after they moved in, meaning that her husband, who has a leg ailment, had no alternative but to walk the eight flights of stairs. The apartment also had serious leaks, and when it rained, water seeped through the walls, leading to a buildup of mold.

Amangozel’ Amandurdyeva and her family were evicted without notice in 2013 from their family home in Ashgabat. Over the years that Amandurdyeva, her sisters, brothers, and parents lived in the house, they had invested in renovation projects and their garden. The home consisted of four large rooms for living space, two enclosed verandas, a dining room, two bathrooms, a shower room, a kitchen, dressing room, pantry, a garage in the courtyard, and a garden with flowerbeds, trees, and grapevines.

Several months passed after Amandurdyeva’s eviction before she was given a new apartment, as authorities had not informed her that she needed to make a written request. When she did, although city authorities told Amandurdyeva she would get a new apartment in an “elite” apartment block, she and her family, including her brother and his family, who were registered at the old home, were forced to move to a three-room apartment in a building in poor repair.

In a letter to President Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov, Amandurdyeva wrote: “the apartments are damp… there are constant leaks. The electricity cuts …Only one of the three air conditioners installed in the apartment works. …There is a stench from the basement, there is constant flooding of sewage, which also flows outside on the street next to the house.” Amandurdyeva has repeatedly appealed to the prosecutor’s office, and she and her neighbors have submitted joint complaints to various government bodies, yet no officials have taken meaningful action to address her concerns.

In another case, in 2015, local officials resettled several families in a substandard dormitory where the toilets and showers did not work properly and that lacked running water at times. The families sent several letters to the Commission for Reviewing Complaints about Officials’ Unlawful Actions, but did not receive a response. Only after the families wrote to the prosecutor’s office did they receive a commitment in writing that they would be resettled in an apartment in Mir (Parahat) 7, in a new building, after it was completed. Human Rights Watch and TIHR have not been able to find out whether and in what manner the commitment to relocate the family was carried out.

Murat M. and his family were left without housing in spring 2017, when the local authorities demolished their property in the Berzengi neighborhood, which borders the AIMAG sport complex, before their replacement housing was finished. Murat was obliged to rent an apartment at his own expense, without reimbursement, even though the Housing Code requires the government to provide for temporary accommodation. After three months, Murat and his family moved into the new apartment, but the building was not properly ready for habitation. For example, the elevator did not work, so Murat’s elderly mother was effectively confined to their eighth-floor apartment.

Demolition Notification

Both the 2013 Housing Code and the Law on Property give homeowners the right to seek legal redress before expropriated property is demolished. However, homeowners need adequate prior notice to exercise this right. Adequate notification of demolition plans, even if there is no intent to bring a legal challenge, is also essential to do work such as dismantling infrastructure in which homeowners have invested – heating systems, tiling and other construction materials, and the like – without damaging them.

Ashgabat residents were not provided adequate notice of pending demolitions, and therefore were denied any opportunity to challenge demolition and had difficulty dismantling their property in a timely manner, often resulting in loss of valuable materials. Gulbahor G., a lawyer who has been monitoring demolitions in Ashgabat for several years, said she is not aware of a single instance in which the authorities issued a proper, timely demolition notice.

Gulbahor G. also suggested that residents do not insist on notification documents for fear that the authorities would construe the request as open confrontation, leaving the residents “living in anxiety not knowing what they would get [in compensation] and when their [homes would be demolished].”

In her letter, Amandurdyeva wrote that her family was evicted and her home demolished so fast that she lost “archives, manuscripts, my father’s large library, everything that my family cherished…and also furniture, dishes, and many valuable things.” The letter also said that people “invited by the municipality dragged off” many plants, trees, and bushes that had been in the family’s garden.

Partial Demolitions

In order to standardize the appearance of many neighborhoods throughout Ashgabat in advance of the games, authorities demanded that residents demolish extensions, outbuildings, gardens, and other property that they had built in order to enlarge their living space. In most, but not all, cases, such additions had been made without permits. If extensions have not been authorized by local authorities or consented to by affected neighbors, the Housing Code’s articles 21-22 allow the authorities to order them dismantled but also grants homeowners a right to seek court approval for such extensions.

However, Human Rights Watch and TIHR were unable to identify a single case in which the authorities granted the homeowners retrospective permission to retain extensions. Nor did authorities make clear to homeowners the legal basis for the widescale demolitions of home extensions in Ashgabat in a manner that would deny their option to seek court approval.

An April 2014 letter from a deputy prime minister to a municipal official, which TIHR and Human Rights Watch reviewed, outlines the government’s plans to beautify the city for the upcoming games and ordered the municipality to “urgently make changes so that the homes and adjacent territories…throughout the city have an appearance that is fitting for a modern, white-marble city.” In almost all cases of partial demolition documented, city officials told residents the outbuildings, gardens and the like had to be removed “because of the [G]ames.”

In March and April 2015, Ashgabat residents described an intense period of partial demolitions that took place in previous months throughout the city, including outbuildings, garages, and summer homes, some of which had been standing for up to 15 years. Demolitions took place all over Ashgabat, in the words of one Ashgabat resident, “literally everywhere in the city where outbuildings, fences, yards and garages could be seen.”

In many cases, local authorities forced residents to pay for the demolitions and offered no assistance to clean up their properties after bulldozers tore down the outbuildings.

Turkmenistan: Berzengi Satellite Imagery

In one case, Merve M. lived on the second floor of a five-story building in central Ashgabat. Fifteen years ago, her family had built out their balcony – resulting in a large extension of her one-room apartment in the back courtyard, and had obtained the necessary permit. In the spring of 2016, municipal authorities forced her to demolish the extension, saying she had restore the property to “its original state.” She was not compensated although the value of the apartment dropped.Lack of Notice

As with full demolitions, city authorities failed to give Ashgabat residents advance adequate notice of partial demolitions – in some cases they gave as little as a few hours – and pressured residents to take down extensions as soon as possible. Sometimes if residents resisted demands to tear down extensions, municipal officials threatened to bulldoze them or to bring the prosecutor’s office to witness the demolition, which could result in unspecific punitive measures against the homeowners.

In the summer of 2016, municipal authorities demolished Boris B.’s outbuildings, including a dining area with kitchen equipment in the courtyard of his first-floor apartment. Boris paid a bribe to city officials when he built the outbuildings in 2009, and until 2016, the officials took no interest in their legality. But when they ordered Boris to demolish the outbuildings, they claimed the property was “illegal” since it was not registered. Early in the summer, local government representatives went around the neighborhood, building by building, to inform first-floor residents that their outbuildings would be subject to demolition. No written order was provided, but the officials told Boris that they were carrying out demolitions in connection with the Asian Games, and said that “after the games are over, you can build it again.”

Dilara D., an Ashgabat resident who lives across from the AIMAG sports complex, said that municipal authorities required her family to demolish their apartment extension in 2015: “We had an apartment with a built-out balcony. [The authorities] forced us to destroy it. It was half the kitchen. We had invested about US$10,000 in that…and had recently done a big renovation. We could save the furniture, but we lost huge amounts of money.”

Another Ashgabat resident, Rahim R., lives on the ground floor of a multistory apartment building. In the spring of 2016, officials from the housing board, municipality, and security services forced him to demolish his terrace, sitting area, and gate, “because of the Asian games.” They also made him fell the trees in his garden.

Threats, Harassment, Short-Term Detention

TIHR and Human Rights Watch also know of four cases in which municipal authorities used threats, harassment, and detention of Ashgabat residents who questioned the municipal authorities’ demands to vacate or demolish their property.

In her letter, Melikohova said that in May 2015, staff of the local government office threatened her and her children with 15 days in detention if they did not vacate their home within 12 hours, even though she was still challenging the eviction in court: “We told them that we had petitioned the Supreme Court and would not move out until we receive copies of the rulings…. The officials replied that we ‘must either move out of the house within 12 hours or we will be arrested together with our kids for 15 days.’”

In 2015, local housing board officials informed Nataliya N. that she had to remove flowers she had planted in the yard of her apartment building in central Ashgabat, claiming that she “had no right” to plant them there as the land belonged to the local government. Nataliya begged the officials not to remove the plants, but they responded by detaining her for 15 days and removed the plants.