A revolution was said to take place in the alternative care industry for children in Japan on August 2 when the Ministry of Health, Labor announced its new vision for such care. The vision is of high quality care with the children’s best interest at its core. The alternative care industry, which provides care for children whose families cannot take care of them, mostly in institutions, was shocked since the plan includes specific numerical goals for moving children out of institutional care. They include moving 75 percent of pre-school children now living in institutions in foster care with families by 2024, as well as ending the new placement of pre-school children in institutions.

Although the public may not have been aware of it, the real revolution for children came in May 2016, in the Diet under the leadership of the then-minister of health, labor and welfare, Yasuhisa Shiozaki. Despite Japan’s overwhelming use of institutions for these children – with 85 percent under institutional care and only 15 percent in foster care, the Diet at that time amended the Child Welfare Act, based on the “principle of family-based care” for children.

However, the industry’s response to the amendment has been slow. The industry had taken the institutionalization of children for granted for decades – in fact since World War II. Following the passage of the amendment, the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare reiterated its instructions to the child care industry to move away from the culture of over-institutionalization. The ministry revised its guidelines to say that "from early childhood, before preschool, adoption and placement with foster parents and family homes shall be the rule.”

Yet, there was no momentum in the industry to respond to this revolution. The industry probably expected that it would be business as usual and that it might be good enough to maintain the status quo. The rules were after all only rules and exceptions would be allowed, its thinking went.

When the specific numerical goals were announced on August 2, the industry for the first time realized it was not going to be the same. In order to provide care that is in the best interest of the children in the future, Japanese society as a whole will have to come together to reform the system to carry out this new vision.

These are the goals under "The New Vision for Alternative Care:"

- Pre-school age children: 75 percent are to be under foster care within 7 years, and no new children will be placed in institutions

- Special Adoption: double the number to 1,000 cases a year within 5 years

- By 2020: Create a structure for a foster care support system throughout the country

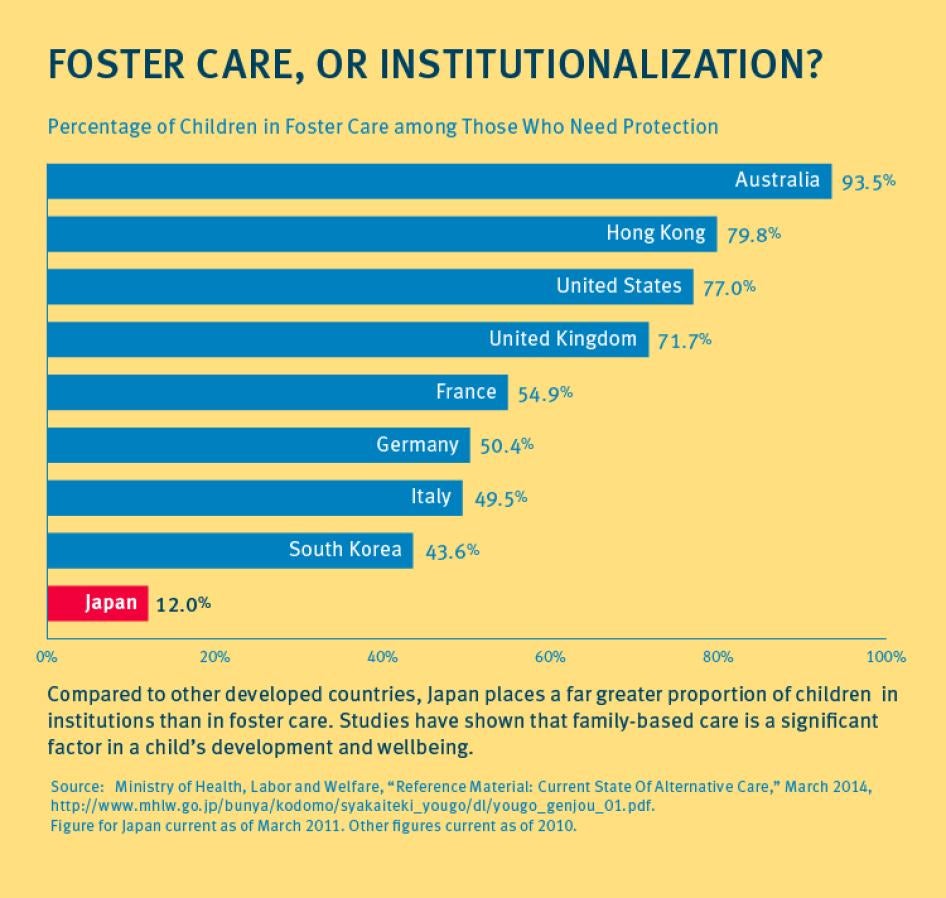

In Japan at present, about 39,000 children have been separated from their parents for reasons such as abuse or a woman’s unanticipated pregnancy. Approximately 85 percent of these children under "alternative care" are cared for in child-care institutions, infant care institutions, and similar institutional arrangements. Fewer than 20 percent of children not living with their own families have found new loving families through foster care placements or adoptions. Because of this, Japan’s "family-separation / over-institutionalization" is inconsistent with the approach in the rest of the world.

In May 2014, Human Rights Watch conducted research on this issue, based on interviews with more than 200 people nationwide, and published an 89-page report: "Without Dreams: Children in Alternative Care in Japan." Since then, Human Rights Watch has been calling for major reforms in alternative care policies, including the current foster care system, to end the over-institutionalization of children.

In some of Japan’s municipalities, people in the alternative care industry welcomed the announcement of a new vision. But people in some cities had the opposite reaction. In the city of Yokohama, where the foster care placement rate was only 13.5 percent at the end of FY 2015, representatives said that "we were surprised by the goal, which is far too ambitious” and that "unfortunately it is going to be difficult to reorganize the system in only a few years." Unfortunately Yokohama’s reaction seems to be the norm. Some expressed the opinion that reforms should move slowly for fear of possible abuse by foster parents and of possible disruptions in foster care situations.

Human Rights Watch has seen such resistance frequently from adults among stakeholders, including those who operate local child guidance centers. However, children who are supposed to be the beneficiaries of the system have had no voice at all. As a result, the inaction symbolized by the attitude of "listen children, you need to wait for decades to have your own families" has continued.

But we should remind adults in the alternative care industry who take that position that living with family is the basic human right for children and that avoiding unnecessary institutionalization is a government obligation (Article 20, paragraph 3 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child). I can only imagine that Japanese society has become numb to the abuses of children’s basic rights because these violations have continued for decades. Children who have lost their precious childhood due to the inaction by adults have repeatedly asked me: “Who will take responsibility?”

Suppose there were virtually no schools in Japan and many children were unable to receive an education. In such environment, would you think that "there is nothing we can do" is an adequate response because building schools is too difficult or you are worried about bullying in schools? Or would it be acceptable to reform the school system gradually over decades? The answer would be no. With the premise of protecting a child's right to education, Japanese society would unite to build schools, improve education systems, take measures against bullying, etc. Parents would become leaders to make sure their children had places to learn as soon as possible.

Living with family is a basic right for children. To make that right a reality, the new alternative care vision calls for comprehensive reform, declaring “No more excuses, let’s unite, allocate budget and human resources to swiftly establish a system that can guarantee children a family.”

It is estimated that about 900 new foster parent couples will be needed every year nationwide to realize the 75 percent foster care placement goal for pre-school age children. That means that prefectures and cities with populations of about 1.2 million people will need 9 new foster couples each year. This is not an unreachable number at all.

I am not saying that it’s easy to get out of the institutional care model that has been in use for all the decades since World War II and quickly shift to a high-quality family care model. But it is important to emphasize that such a change is absolutely necessary for children. The new vision requires changes in many systems and practices. One of the most important reforms will be the prompt introduction and improvement of high-quality agencies to provide a comprehensive support structure for foster parents.

This comprehensive support system will team up with foster parents to provide consistent recruitment, training, support, and other necessary services. Good organizations to provide support to foster parents are essential; for anxious new foster parents, and above all, for children, who should be guaranteed high quality foster care without abuse or problems with their foster parents.

Unfortunately, there are still very few organizations in the country to provide these services. One way they could be expanded swiftly around Japan is for both national and local governments to provide political support as well as enough funds and resources so that existing child care institutions and nongovernmental organizations with experience working with children can develop as high-quality providers of support services for foster care. The new vision calls for developing these support services nationwide by 2020.

Some institutions that care for infants had transformed their own structures even before the new vision was announced. For example, the Uedaminami infant institution in Nagano prefecture plans to shift its business model within three years from an institutional one to an organization to support foster parents and pregnant women and mothers. Their project is seen as a pilot effort to shift infant care institutions to private foster care-support agencies by reassigning and retraining staff, while making full use of their own experiences and the local trust they have built. The other 200 infant institutions in Japan can use this effort as a reference, and I hope that others will follow its path for the sake of institutionalized infants. Such valuable experiences gained through these pilot efforts by progressive infant institutions should be utilized nationwide.

The current budget system for alternative care institutions is that each institution receives funds based on the number of children institutionalized. In other words, Uedeminami has undertaken its reforms for the sake of children’s needs while facing possible fund cuts. A census of the number of institutionalized children is taken every three years, so their funding will be the same for two more years. To expand this kind of effort nationwide, it is necessary to abolish budgetary incentives based on placements in institutions, and introduce new incentives based on transferring children to families.

The new vision suggests not only developing policies for agencies to support foster families but also establishing a social work structure, developing a third-party evaluation system, and creating a system of advocates for children. The new vision also requires promoting special adoption as a durable solution to assure permanency, foster care system reform, reform of child guidance centers and the temporary custody system, and supporting children’s independence. Each element is extremely important, so it is essential to provide both budget and staffing adequate to create all of these components. Then, for the first time, the vision will become reality.

The movement away from institutions to families is finally happening in Japan - decades behind many other developed countries. This means that Japan could learn from mistakes that other countries have made during their transition and deinstitutionalization and avoid them – including frequent foster placement disruptions.

Finally, let us focus on what each of us can do in the spirit of Jack Kennedy’s famous saying, ”Ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country.”

Even if both national and local governments take all measures of the new vision, “children's rights to live with families” cannot be accomplished without the involvement and good will of many citizens. Each of us should do what we can. People should consider becoming foster parents as one way to contribute to their own society. Raising a child is an opportunity to see a child grow and develop to lay their own path for the future. Such an experience is irreplaceable.