A journalist prosecuted for allegedly helping a group which he spent years criticizing in his work. Emails received – but not answered – from people the government views as undesirables, and newspaper clippings presented as evidence of criminal wrongdoing. A cartoonist in the dock.

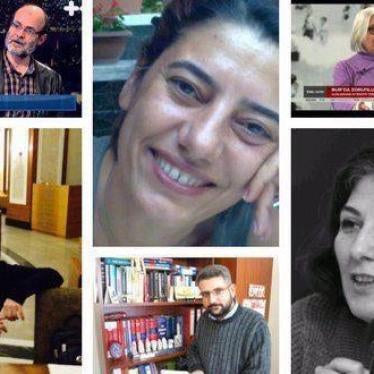

Kafkaesque is an over-used term. But it seems appropriate when trying to capture the prosecution of 17 journalists, editors, and other staff at Cumhuriyet newspaper that began this week over charges that they have aided and abetted groups the government has designated terrorists.

That the groups in question – the armed PKK group and the Gulen movement – have diametrically opposed agendas hardly seems to matter.

And the evidence against the defendants appears to consist largely of the newspaper’s content: articles, op-eds, as well as social media posts and phone records. There appears to be nothing that would indicate any kind of criminal wrongdoing, much less helping terrorism.

Cumhuriyet has been in the state’s sights for some time. Its former editor Can Dündar and the Ankara bureau chief Erdem Gül were convicted in May 2016, and sentenced to more than five years’ imprisonment for allegedly revealing state secrets by publishing video and photographic evidence of arms being sent to Syria. They are still on trial in a separate process accused of aiding a terrorist organization. An opposition member of parliament alleged to have shared the footage of the arms transfers with the newspaper was jailed in June.

The Cumhuriyet staff are hardly alone. As a recent Human Rights Watch report showed, critical journalism has been under assault by the Turkish state for several years, with the crackdown greatly accelerating after the failed coup attempt in July 2016.

Over the past year, hundreds of outlets have been shuttered or taken over under state of emergency powers. More than 160 journalists and media workers are now in prison or pretrial detention, according to Turkish media watchdog NGO P24. They include 10 of the Cumhuriyet staff currently on trial.

For those hoping that the courts will see the flimsy evidence brought against journalists for what it is, it is worth noting that in March, a court ordered the release on bail of a group of journalists who had already been in pretrial detention for an extended period. But after criticism in pro-government media that decision was reversed and the judges involved were suspended from duty.

International scrutiny of Turkey’s record on media freedom and solidary for its embattled journalists has never been more important.