What is it like in Recife and Campina Grande, the cities in northeastern Brazil that you visited?

AK: What was shocking to me was the vast inequality. There are these beautiful high-rises and a beautiful beach in Recife, and then there are communities that are really suffering. And Zika is just one way that they are suffering. You have very poor water and sanitation conditions right next to shiny malls. It’s the type of inequality you can see around the world, but you never get used to it.

MW: I was interviewing a pregnant woman, and she was walking me around her community, pointing out how untreated sewage was pooling on the uneven roads right in front and behind her house, and she couldn’t afford to buy insect repellant and protect herself. Her only defense against the mosquitos that were swarming around her community was a fan in her house. Her vulnerability and her inability to protect herself during her pregnancy was really stark.

Did the women and girls you spoke with have information about how to protect themselves?

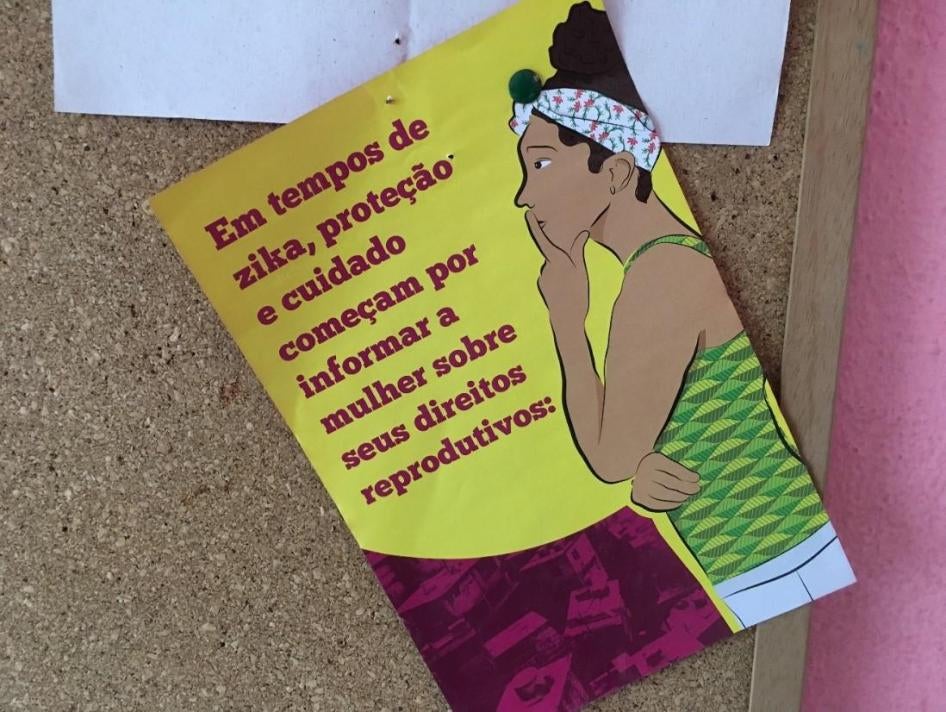

MW: We interviewed a lot of pregnant women and girls to try to assess what types of information and services they were getting during the outbreak. The one thing that emerged so clearly was that the women and girls we interviewed had very limited information about the sexual transmission of Zika. Even though Zika is transmitted primarily by infected Aedes mosquitos, the virus can also be transmitted sexually, and pregnant women should use condoms with their partners if they’re living in an area with Zika. The women we interviewed had all heard about Zika on the news, and their healthcare providers were talking to them about wearing insect repellant and cleaning up standing water. But very few women knew the virus could be transmitted sexually, so they didn’t know to use condoms with their partners. I told this to one 16-year-old girl, and her jaw dropped because she had never heard of this and had no idea.

AK: It was such a contrast to me how easily we could find information about Zika in preparation for our trip, and how pregnant women living there weren’t given that information or that opportunity to protect themselves.

Why weren’t women – and particularly pregnant women – given this information by their healthcare providers?

AK: At the federal level, there was conflicting information about the possibility of sexual transmission. And that was early on, and sometimes that sets the tone of how much importance to put on it. The possibility of sexual transmission wasn’t being communicated to the clinics or providers in at least one state, and it wasn’t communicated down in a consistent way across the system.

The government said the public health emergency had ended. What does this mean, and what changed so they could make that claim?

MW: The Ministry of Health declared that Zika was no longer a public health emergency of national concern, which doesn’t mean that the virus is gone or that the threat is gone. It basically means that the outbreak of Zika is no longer unusual or unexpected. It no longer meets the World Health Organization’s criteria for a public health crisis. The argument that the Ministry of Health made was that that they have sufficient plans in place to say that this is no longer a national emergency.

Our fear is that people will hear the announcement and think, “Zika’s over, the risk is gone, I don’t need to worry about this anymore.” When, in fact, the underlying conditions that allowed the virus to spread so rapidly have not been addressed. In 2017, the number of cases of the virus and of children born with Zika syndrome are dramatically lower than they were in the same months in 2016, so that’s encouraging. That shows us something is happening that’s allowing the virus to be better controlled. But the conditions that made the epidemic so severe in the first place have not been fixed.

Why have the numbers dropped dramatically?

AK: It’s hard to determine why. It could be that the use of mosquito-killing pesticides had an effect, that there’s increasing immunity, or that it was a drier season, so the mosquitos haven’t bred. But those are not indicators of long-term success. You only have to look at how other mosquito-borne viruses like dengue and chikungunya have ebbed and then peaked over the years to see that the danger of another Zika epidemic is still there. The underlying conditions that exacerbated the Zika outbreak – failing water and wastewater systems – haven’t been fixed. The mosquito that carries these viruses is still present in Brazil. For us, the concern is that people will assume the crisis has passed.

What steps has the government taken to address the virus?

MW: They put a lot of resources and efforts into trying to control the mosquito population. But this was largely focused on the household level, and visits by environmental agents to check water storage containers. The missing piece, and our main argument in the report, is that this response did not include making sure people have consistent access to running water, so they don’t have to store water in ways that lead to mosquito breeding, and facilities to treat human waste. And it’s tough, because Brazil is facing one of the worst economic recessions that it’s seen in decades. But even in times of economic growth, the investments in the water and sanitation infrastructure were inadequate.

What concrete steps can the government take to help parents raising children with Zika?

MW: In families raising children with Zika syndrome, the caregivers are overwhelmingly the mothers. The lives of these women and girls are profoundly affected by raising children without the support they need. They are juggling lots of appointments and battling local municipal authorities to get the types of tests and consultations that their children need. Their lives are extremely chaotic. Also, families living in rural areas sometimes have to leave their houses at 3 or 4 in the morning to take their children to doctor’s appointments in cities, a demanding and exhausting routine for them. For some families, it’s waiting for public transportation that never comes and scrambling to find another way to get to the appointment.

The government should make it easier for these families to get the services their children need. The Brazilian public health system can decentralize services so that rural families can find them – or, at least, the services that their children need most often – closer to home.

AK: For example, the government can make some services – like physical therapy and occupational therapy – more accessible, even with the current fiscal restrictions, by reorganizing the services geographically.

MW: I think there was a real fear among some of the parents we interviewed that, as the news of Zika faded from the headlines, their children would be forgotten. As time goes on, their children are still going to need services. A lot of families were worried that they won’t have the long-term support they need.

This interview has been edited and condensed.