UPDATE: As of June 20, 2017, Egyptian security forces had arrested 190 political activists over the course of two major campaigns that began in April, according to a report by the Egyptian Commission for Rights and Freedoms. Among those arrested were members of the Constitution and Dignity parties and the April 6th Youth Movement. The arrest sweeps appeared to be timed to precede and encompass the mid-June parliamentary debate over President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi’s decision to turn over to Saudi Arabia two Egyptian islands in the Red Sea, a move which had sparked protests in the past.

One of those arrested was human rights lawyer Tarek Hussein. In violation of a June 18 prosecution decision ordering him released on bail, officers of the Interior Ministry’s National Security Agency continued to order Hussein detained as of June 23.

In an apparently coordinated action, unknown authorities also blocked access in Egypt to scores of websites, the majority of them connected with the news media. At least 103 websites were blocked between May 24 and June 22, 2017, according to the Association for Freedom of Thought and Expression. They included many news outlets, such as Mada Masr, as well as a website advocating against the transfer of the Red Sea islands.

(Beirut) – Egyptian authorities in recent weeks have arrested at least 50 peaceful political activists, blocked at least 62 websites, and opened a criminal prosecution against a former presidential candidate, Human Rights Watch said today. The actions are further closing any remaining space for free expression.

The charges against the activists appear to be based on peaceful criticism of the government and some local law provisions, such as insulting the president, that inherently violate the right to freedom of expression. At least eight face possible five-year prison terms under Egypt’s 2015 counterterrorism law for their posts on social networking sites. The website blocks affected major Egyptian and international news organizations as well as political groups.

“Egyptian authorities are using the pretext of fighting terrorism to crush peaceful dissent,” said Joe Stork, deputy Middle east director at Human Rights Watch. “The government isn’t going to make inroads against extremists by shutting down peaceful opposing voices.”

Among those arrested was a prominent human rights lawyer, Khaled Ali, whom prosecutors called for questioning on May 23, 2017, and subsequently sent for a fast-track trial on the charge of “committing a scandalous act” in public. Ali ran for president in 2012, coming in seventh with about 134,000 votes. He has signaled interest in challenging President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi in the 2018 presidential election.

The wave of arrests during April and May was reported by Freedom for the Brave, an independent Egyptian group that tracks such arrests.

On June 1, the group released a detailed list of the 42 people detained, showing that 29 remained in custody, four of whom had already been sent to trial. Many were active in movements critical of the government, including the nascent Bread and Freedom Party.

Prosecutors accused 17 of membership in prohibited groups, including the Muslim Brotherhood and the April 6 Youth Movement. On June 13, Interior Ministry forces arrested five more activists and three journalists from around the Journalists Syndicate in downtown Cairo.

The government invoked article 28 of Law 95/2015 for Confronting Terrorism to charge at least eight activists with “propagating ideas or beliefs advocating the commission of terrorist acts.” The charges stemmed from Facebook posts, according to a statement by six Egyptian rights groups. Mohamed Walid, a Bread and Freedom Party member from Suez, was arrested after posting, “I am neither pro-Mubarak nor do I belong to the Muslim Brotherhood, I just want to live as a human being,” as well as “down with the military rule” and the slogan of the Bread and Freedom Party, “bread and freedom for all people.”

Human Rights Watch reviewed the prosecution file for Andrew Nassef, also charged with “promoting terrorism.” It stated that prosecutors seized publications and banners from his home that were critical of the government, such as “January 25 Again,” a reference to the 2011 uprising, and “Release Egypt.” Nassef’s Facebook posts cited in the file included: “When will we overthrow the prisons and military dictatorships again,” and, “Seek freedom and talk about every oppressed person in the country whether you know him or not (…) because one day it will be your turn.”

Other detainees are accused of insulting the president, spreading false news, or using social networking sites to incite against the state or advocate the overthrow of state institutions.

On May 24, Egyptian authorities imposed a coordinated blackout on at least 21 websites, most belonging to news organizations, for allegedly “supporting terrorism and spreading lies,” according to an unnamed senior security source who spoke to the official Middle East News Agency. The Association for Freedom of Thought and Expression, an independent Egyptian rights group, said the block had grown to 62 sites as of June 12.

Among those affected were Egyptian news websites such as Mada Masr, Masr al-Arabiya, and Daily News Egypt; Turkish news websites; international news websites such as Al Jazeera and the Huffington Post’s Arabic edition; the official websites for the Muslim Brotherhood and the Palestinian movement Hamas; and the website for the Tor Project, which supports internet anonymity.

The move occurred hours after Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates blocked access to Al Jazeera and other Qatar-based websites, ostensibly in reaction to statements by Qatar’s emir published by Qatar’s state news agency. The apparently coordinated effort by Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and other allied countries to isolate Qatar stemmed from years of anger at Qatar’s foreign policy and has in recent days extended to Saudi Arabia and the UAE severing all ties and closing air, land, and sea transportation to Qatar.

Qatar claimed that the statements attributed to the emir were false and that its news agency had been hacked. The United States Federal Bureau of Investigation and British law enforcement officials supported that assessment, media reports said.

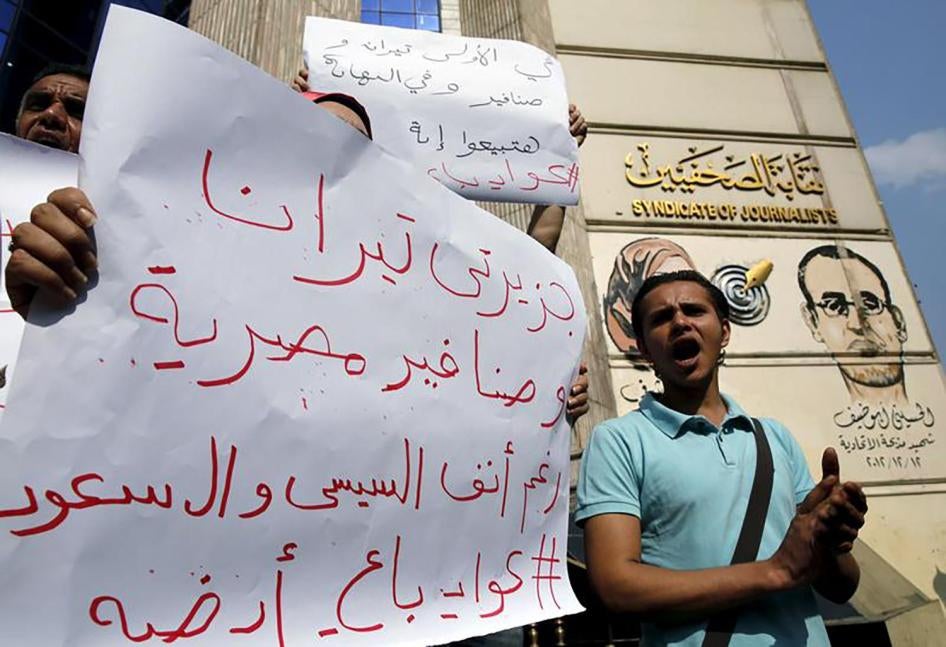

Egypt has gone further, extending its censorship to domestic opposition movements, including by blocking a website for the National Popular Campaign to Defend the Land, which opposes a plan by al-Sisi to cede two Red Sea islands to Saudi Arabia. The Sisi administration has sought parliamentary approval to move ahead with the plan, despite court rulings that it is illegal. It went before the parliament for debate on June 11 and 12, and parliament approved the decision on June 14. On June 13, while activists gathered at the Journalists Syndicate to protest the agreement, Interior Ministry security forces surrounded them and arrested some. At least eight, including three journalists, are being held for investigation by prosecutors for protesting without a license.

On May 31, representatives of four websites, including Mada Masr, said they would file a joint complaint to the prosecutor general on the basis that the block was unlawful.

Ali, the lawyer and former presidential candidate, was also a key member of a legal team that successfully challenged the decision to cede the two islands to Saudi Arabia. He was accused of making an obscene gesture with his middle fingers during a celebratory street protest following the Supreme Administrative Court’s ruling on the Red Sea islands issue in January. The charge is punishable with a sentence of up to one year or a fine of 300 pounds (US$17) under article 278 of Egypt’s penal code.

Ali’s lawyers told Human Rights Watch that they fear that a conviction on a charge of public indecency would probably prevent Ali from running for president in 2018, since elections laws disqualify those sentenced for “crimes that undermine honor.” No law defines such acts, but the lawyers said that Egyptian courts have interpreted sexual gestures or conduct as offenses that undermine honor.

Though many countries criminalize offenses to public order, prosecuting someone for making an obscene gesture during a peaceful protest would be an unreasonable limitation on freedom of expression, and it would be disproportionate to penalize such an act with imprisonment or the forfeit of political rights, Human Rights Watch said. The Dokki Misdemeanour Court for Minor Offenses in Cairo has scheduled Ali’s next hearing for July 3 and ordered that defense lawyers be allowed to obtain the case file.

Egypt’s constitution, in article 57, states that it is “impermissible” to deprive citizens of the right “to use all forms of public means of communications” or to interrupt or disconnect them arbitrarily. Article 71 states that “it is prohibited to censor, confiscate, suspend or shut down Egyptian newspapers and media outlets in any way.”

However, Egypt’s 59-year-old emergency law, which al-Sisi invoked on April 11 after deadly twin church bombings by the extremist group Islamic State, allows the authorities to censor publications at will. After al-Sisi declared the state of emergency, Ali Abdel Aal, the parliament speaker, said that social media websites such as Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube would fall under its surveillance and censorship provisions, the newspaper Al-Masry al-Youm reported.

The Human Rights Committee, the body of independent experts that monitors implementation of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, stated in its general comment 34 that the prohibition of “a site or an information dissemination system from publishing material solely on the basis that it may be critical of the government or the political social system espoused by the government” constitutes a violation of the right to free expression. Egypt ratified the covenant in 1982.