“Daniel Soto” was 18 when, he says, a stranger stabbed him outside of a McDonald’s following an argument – slicing him from his chest to his belly button. When his mom, “Maria Soto,” got the phone call from the hospital the next day, the distressing news didn’t end there: Daniel was also under arrest, charged with felony assault.

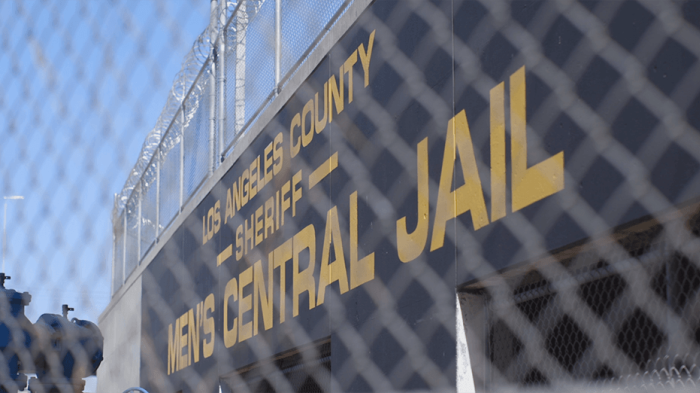

Daniel wasn’t carrying a weapon. He had no criminal record. He was not ultimately convicted of any crime. But Daniel wound up in jail. He was held for six long weeks – missing school – because his single mother couldn’t afford to post bail, set at the astronomical amount of US$30,000. The judge who set bail hadn’t heard any evidence in the case and did not consider Daniel’s individual circumstance.

Ultimately, a judge dismissed the case, but it was too late for Daniel to get those six weeks back.

Daniel, whose name along with his mother’s has been changed to protect their privacy, is one of tens of thousands of Californians every year who are held in jail for days, weeks, months, or even years without ever being convicted of any crime because they cannot pay bail. In fact, between 2011 and 2015, close to half a million people – one in three people arrested on felony charges – were held in jail or had to pay bail, but eventually were determined not to be guilty of any crime.

How California’s Pretrial Detention and Bail System Unfairly Punishes Poor People

A new Human Rights Watch report, “‘Not in it for Justice’: How California’s Pretrial Detention and Bail System Unfairly Punishes Poor People,” examines how the state’s broken system forces those who can’t post bail – often set at ridiculously high rates – to remain locked up or go into massive debt by paying non-refundable fees to bail bondsmen. Many people who would otherwise contest their charges plead guilty, accepting a sentence of time served, community service, or probation. They do this because they fear losing their jobs, or having their children taken away while they are behind bars, or because they just cannot stay in jail, but it leaves them with a criminal record.

After Daniel was stabbed, on November 2, 2015, doctors operated on him overnight in a Los Angeles County hospital. His wound required emergency surgery and 19 staples. When his mother finally got the call the next afternoon, she rushed to the hospital. But because Daniel was under arrest – and handcuffed to the hospital bed – she was not allowed to see him. She snuck in anyway, for a few minutes, until guards spotted her and forced her to leave.

Daniel spent a week in the hospital before officers took him to jail, where he received minimal treatment: they gave him Advil for pain, and occasionally nurses changed his bandages, but nothing more. He had been assigned the top bunk, so getting into and out of bed was excruciating. Daniel described how pus would ooze from the wound because of the exertion.

On November 10, Daniel appeared in court for his arraignment, where he pled “not guilty.” The judge, following the bail schedule for a felony assault charge, set bail at US$30,000.

While judges have discretion when setting bail, they rely heavily on “bail schedules” – a list recommending set bail amounts for various crimes. Each California county has its own bail schedule, which does not take into consideration the risk the individual poses to the public. One judge even told us that judges, when creating bail schedules, did not base their decisions on any actual data. But one aspect of bail schedules is consistent across almost all California countries: bail is generally excessively high. Studies have found that California’s median bail is five times greater than the median bail for the rest of the country.

Maria, a single mother who worked as a stenographer, did not have that kind of money. She earned enough to pay rent and bills and support herself and her two sons, but she didn’t have savings or property to sell or use as collateral. She spoke to various bail bondsmen, but none would give her a payment plan she could afford. Bail bondsmen charge a nonrefundable fee of 7-10 percent of the total bond amount.

Studies have found that California’s median bail is five times greater than the median bail for the rest of the country.

Maria felt helpless: “It was very depressing…. It was terrible. He’s my son. I wasn’t eating. I wasn’t sleeping. I just worried about him.” Over the next five weeks, she managed to visit him a few times, but visiting hours are limited and waiting times are long. Phone calls are expensive, making any communication costly.

“I just had to ride it out,” Daniel said. He spent Thanksgiving in jail, missing out on the annual gathering at his uncle’s house. Maria recalled how depressing it was to be “celebrating” Thanksgiving while her son was in jail and there was nothing she could do about it.

Meanwhile, Daniel was missing school. Then, on December 17, he appeared in court for his preliminary hearing. It was the first time a judge would actually hear any proof of the crime. The prosecutor’s witnesses testified, Daniel’s lawyer cross-examined, and finally, the judge dismissed the case, saying there was no evidence that Daniel had committed a crime.

Maria brought her son home, but those six weeks in jail would have a lasting impact on Daniel, although he tries to avoid revisiting or dwelling on the case now. He had to drop out of school that semester, and simply never went back – he always struggled as a student, and felt he could never catch up.

But what if Daniel’s family had been able to post bail? What if the judge made prosecutors prove that it was necessary to set bail, before his six-week jail stay? Or what if the judge had considered his circumstances when setting the amount of bail? Daniel’s story – and the story of hundreds of thousands of others – underscores why California’s bail system is badly in need of reform.