Summary

On the night of November 2, 2015, Maria Soto’s 18-year-old son Daniel went out with friends and did not come home. At 1:30 p.m. the next day, Maria finally got a call: Daniel had been stabbed and was in the hospital—and was under arrest.

A man had accosted Daniel and his friends outside of a restaurant. They had fought, and the man pulled a knife. Cut and bleeding, Daniel staggered up to a police officer, who called an ambulance and arrested him. Apparently, the man with the knife had gotten to the officer first.

Once he arrived at the hospital, Daniel received minimal medical treatment—Advil for pain and occasional new dressings for his wound. On November 10, he was taken to court, where he pled “not guilty” to a felony assault charge. The judge set bail at $30,000.

Maria, a single mother who worked as a stenographer, made enough to pay rent and bills for herself and her two sons, but had no savings and no property to sell or use as collateral. No bail bondsmen would give her a payment plan she could afford.

Maria felt horrible, knowing her son was hurting, locked up in jail, and there was nothing she could do to help him. “It was terrible. He’s my son. I wasn’t eating. I wasn’t sleeping. I just worried about him.”

Meanwhile, Daniel also could not sleep, due to the pain from his injury and the hard jail bed. He was assigned a top bunk and struggled to climb up to it. Sometimes pus would ooze from his wound due to the exertion. He asked his mother to bail him out, but understood she could not come up with the money. “I just had to ride it out,” Daniel said. He missed school and slipped behind in his studies. On Thanksgiving, Maria and the rest of the family ate their meal without him.

Finally, on December 17, over six weeks after his arrest, Daniel had his preliminary hearing—the first opportunity in court for the judge to hear proof of the crime. The judge dismissed the case, saying there was no evidence he committed a crime. Daniel was able to go home, but he had lost a semester of school and a month-and-a-half of his life to jail for a crime he did not commit, all because his family did not have money to pay for his freedom.

***

Tens of thousands of people arrested for a wide range of crimes spend time locked up in jail because they do not post bail. Nearly every offense in California is bail-eligible, yet many defendants cannot afford to pay. In California, the majority of county jail prisoners have not been sentenced, but are serving time because they are unable to pay for pretrial release.

This report concludes that California’s system of pretrial detention keeps people in jail who are never found guilty of any crime. The state jails large numbers of people for hours and days against whom prosecutors never even file criminal charges. People accused of crimes but unable to afford bail give up their constitutional right to fight the charges because a plea will get them out of jail and back to work and their families. Judges and prosecutors use custody status as leverage to pressure guilty pleas. As one Californian who went into debt to pay fees on $325,000 bail for a loved one who was acquitted said, the actors in California’s bail system are “not in it for justice.”

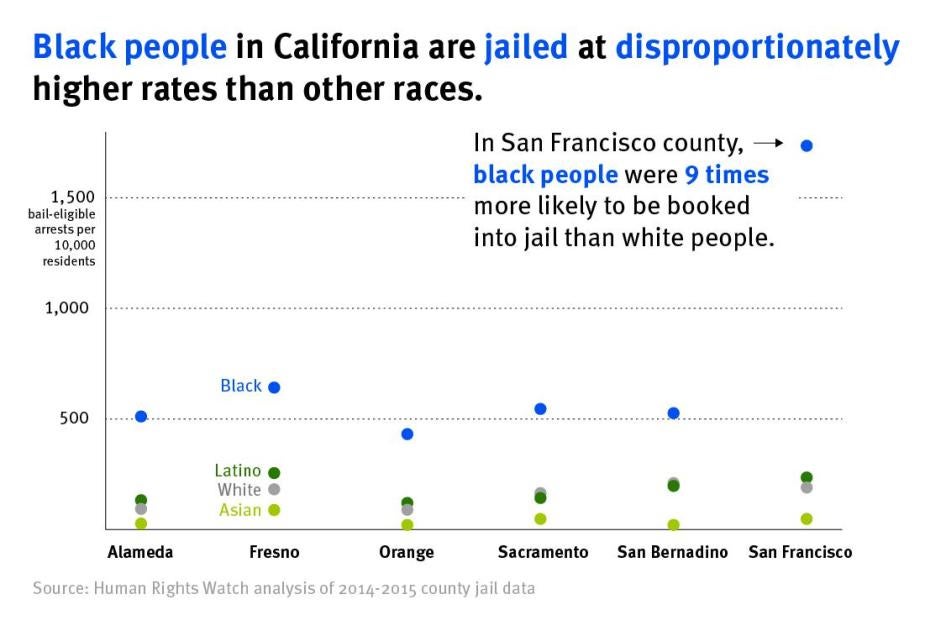

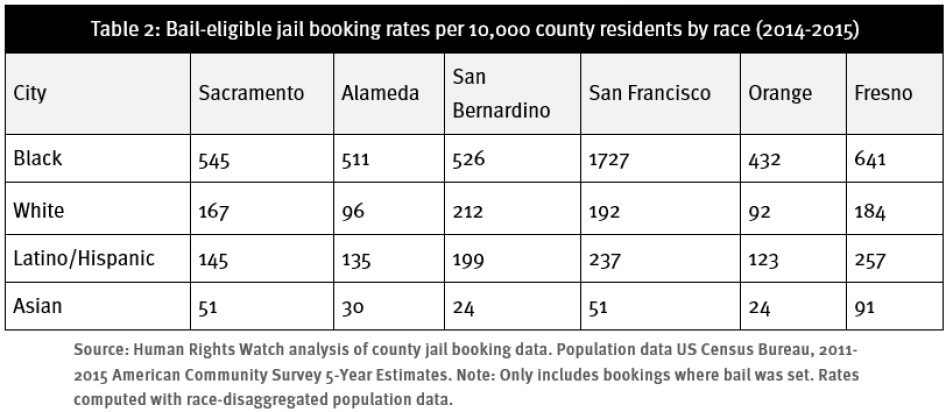

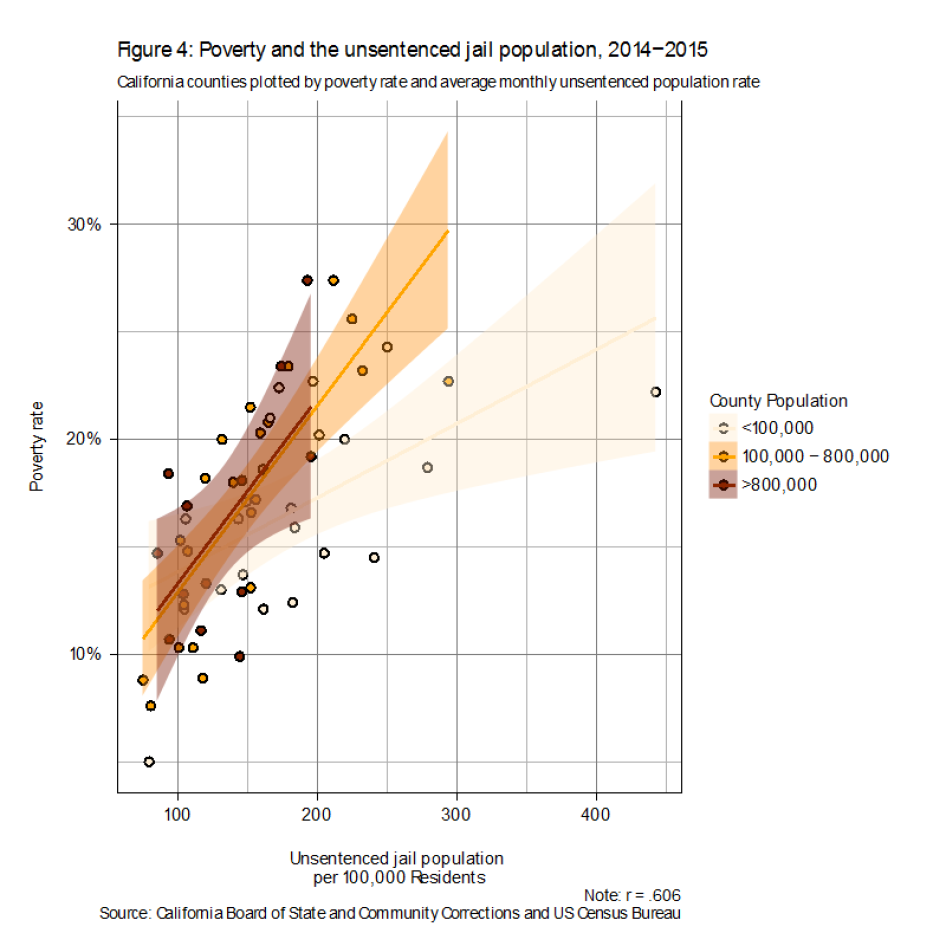

Those locked up pretrial are overwhelmingly poor, working class, and from racial and ethnic minorities. California’s median bail rate is five times higher than that of the rest of the country. There is a clear correlation between the poverty rate and the unsentenced pretrial detention rate at the county level in California. The state is also plagued by profound racial disparities in pretrial detention rates due to racial disparities in arrest and booking rates. The rate at which black people are booked into California jails is many times higher than for white people—for example, it is nine times higher in San Francisco.

Bail and pretrial detention in California subject arrestees to unfair treatment, arbitrary detention, wealth discrimination, and other violations of their basic rights. People unable to pay bail remain in jail regardless of guilt or innocence. Poor and middle-income people incur debilitating debt to gain the advantages to fighting their cases that pretrial freedom bestows.

There is an alternative to California’s system of money bail and pretrial detention. Given the large numbers of people locked up in California despite never being charged with an offense, as well as the large numbers of low-level offenders who are jailed, the best reform would divert the great majority of defendants out of custody through extensive use of release with citations. The remainder would have detailed, individualized hearings before a court could order pretrial detention.

This alternative to money bail as the determinant for custody would reject the current trend of using profile-based statistical predications of risk instead of money bail as the basis for pretrial detention or supervision decisions. Instead, it would rely on detailed, individualized hearings to determine whether any pretrial defendant may be deprived of their liberty.

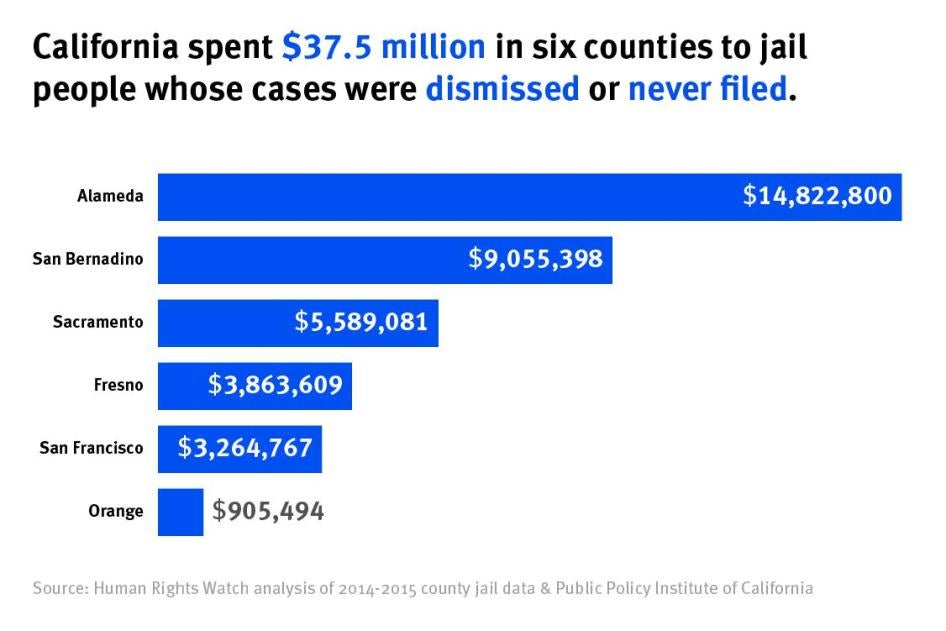

Wrongful Pretrial Detention

From 2011-2015, police in California made almost 1.5 million felony arrests. Of those, nearly one in three, close to half-a-million people, like Daniel Soto, were arrested and jailed, but never found to be guilty of any crime. Some spent hours or days behind bars. Some spent weeks; others, months and even years. The cost to taxpayers of this pretrial punishment is staggering: each day a person is held in custody costs an average of $114. In six California counties examined in detail in this report (Alameda, Fresno, Orange, Sacramento, San Bernardino, and San Francisco), the total cost of jailing people whom the prosecutor never charged or who had charges dropped or dismissed was $37.5 million over two years.

Over a quarter-of-a-million people sat in jail for as long as five days, accused of felonies for which evidence was so lacking prosecutors could not bring a case. Many were victims of baseless arrests; others, mistakes of judgment or misunderstandings of the law. The remainder had cases filed, but lacked sufficient proof of guilt, resulting in eventual dismissal or acquittal after weeks and months in jail. A large percentage of these not guilty people either had to pay bail, often plunging themselves or their families into crushing debt, or had to contest their cases while locked up in county jails.

These nearly half-a-million people spent time in jail at taxpayer’s expense, missing work, not picking their children up at school, not caring for elderly parents, missing classes, and subject to violence and miserable conditions, because they did not post bail. They were punished for crimes they did not commit, not because they were too dangerous to release, but because they could not come up with money to pay for their release, in cases where the criminal justice system ultimately found them not guilty.

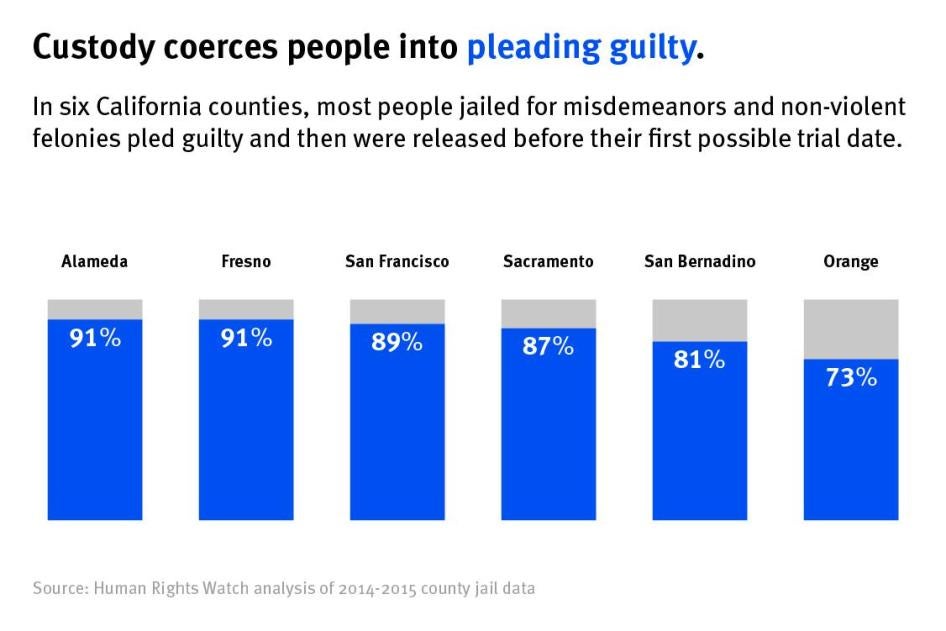

Coerced Guilty Pleas

Many Californians accused of crimes, but unable to afford bail, give up their constitutional rights to fight the charges because a guilty plea will get them out of jail. Prosecutors often argue for high bail because a defendant is “too dangerous to let out” before trial, then offer the same “dangerous” person a time-served, go home sentence in exchange for a guilty plea. Some judges set bail a defendant cannot possibly pay, to encourage guilty pleas for the sake of rapid processing of cases.

Pretrial detention causes higher conviction rates mainly by coercing people to plead guilty in order to get out of jail sooner. In the six counties analyzed from 2014-2015, 71-91 percent of misdemeanor and 77-91 percent of felony defendants who stayed in jail until they received their sentence were released before the earliest possible trial date. They all pled out before they had a chance to assert their innocence. Pretrial detention allows courts to process cases more quickly, but distorts justice by coercing guilty pleas.

A Discriminatory System

California’s system of money bail and pretrial detention discriminates based on wealth. Rich people simply pay bail and buy their freedom. People of more modest means sometimes can cobble together the money to pay a bondsman the 8-10 percent non-refundable fees normally charged to secure their release. In the six counties examined in detail, 70-80 percent of arrestees could not, or did not, pay bail. Those who did not pay were either eventually released from jail in other ways, such as on their own recognizance or by court orders, or stayed in jail until they were sentenced. People at liberty can help with their defense; they can go to work, go to school, attend a drug rehabilitation program or enroll in psychological counselling, all of which can show the judge there is no need to punish harshly; they appear in court showered and groomed, in their own clothes, not jail uniforms.

People who cannot afford bail have none of these advantages. They have barriers communicating with their lawyers; cannot help locate witnesses and evidence; cannot participate in programs to improve themselves and make themselves look better in the court’s eyes; and cannot earn money. They sit in jail, surrounded by misery, feeling stress about the case, unable to get calm advice from family and friends. They cannot sleep well. They will look like criminals when they appear in court, shackled or behind a glass partition. Many judges are likely to see them as just another defendant to process.

|

The case of Daria Morrison and Sarah Jackson illustrates the income-based discrimination in California’s money bail system. Both women were arrested together and charged with a robbery; neither had a prior criminal record. Yet their fates were very different. Daria had sufficient help to pay the bondsman’s fee, was released from custody, and offered a reduced charge that will result in a dismissal in one year by the prosecutor. Her co-defendant, Sarah, equally culpable for the crime, remained behind bars, unable to pay for bail. She ended up pleading guilty to two serious felony charges. |

The bail system is also racially discriminatory. Though violent crime has dropped steadily since the early 1990s, California continues to put people in jails and prisons in massive numbers. On a single day in 2015, California had 201,000 people behind bars, with 1.15 million arrests throughout the year, causing many thousands more to cycle through the jails during the year. This high rate of incarceration disproportionately affects black people, who are over 6.5 times as likely as white people to be locked up. Data analyzed by Human Rights Watch from a variety of California counties shows jail booking rates for black people are significantly higher than for white and Latino people.

High Bail

In this time of increasing incarceration, the use of pretrial detention has also increased dramatically. In California, consistently over 63 percent of prisoners in county jails have not been sentenced, but are serving time because they cannot afford to pay bail. Studies have calculated California’s median bail as being five times greater than that for the rest of the country.

California law does not require a judge to inquire into a defendant’s ability to pay, and judges rarely do when setting bail amounts. Instead, they rely on arbitrarily determined bail schedules that set amounts to coincide with the level of the charge. While judges have discretion to depart from them, they tend to treat the schedules as mechanical formulas to apply in most cases. Experts and advocates―and even some judges―told Human Rights Watch that bail in California is set to keep people in jail, coerce guilty pleas, and make court machinery move more rapidly.

Most defendants rely on bail bondsmen to get out of detention. Bondsmen charge a fee of up to 10 percent of the actual bail amount, which is not refundable, even if the case is dismissed or charges are not filed. Bondsmen charge as much down-payment as they can, sometimes the full amount of the fee, or work out payment plans that they enforce with the threat of revoking the bond and sending the accused back to jail.

This system often means that poor and middle-income families must borrow from friends and family, raid retirement plans, cut back on food, bills, and holiday presents, miss rent payments, and sell personal property to pay for their loved one’s freedom.

|

While the numbers are staggering, the true measure of the harm caused by California’s system of money bail is in the stories of the people who have been through this system:

|

Bail: An Ineffective Tool

The stated purposes of setting bail are to protect public safety by preventing potentially dangerous people from causing harm before their cases are adjudicated and to prevent people from fleeing the jurisdiction or otherwise evading their obligation to go to court.

But bail is not a particularly effective tool to meet these goals. Lack of in-depth, individualized hearings means judges do not have sufficient knowledge to assess risks with accuracy, defaulting to bail schedules and overusing detention. Vast numbers of people are jailed pretrial due to “dangerousness,” while only a tiny percentage actually commit violent crimes while awaiting trial. People with money pay for release regardless of how dangerous they are.

Few people actively evade court. Most who fail to appear do so due to negligence or error, homelessness or mental disabilities, or because they cannot miss work or find child care. Many who miss appearances eventually return to court on their own. Imposing bail improves court appearance rates in moderate amounts, but detains many more people than is necessary. Other pretrial services, like reminder calls, are proven to reduce missed court dates without incurring the costs of locking people in jail.

International human rights law permits the use of pretrial detention and money bail, but only if they are limited and are consistent with the right to liberty, the presumption of innocence, and the right to equality under the law. A person's liberty may not be curtailed through arbitrary laws or the arbitrary enforcement of law in a given case. International human rights law condemns discrimination based on race, ethnicity, gender, and wealth. Decisions about pretrial detention must be grounded in reasoning that contains specific individualized facts and circumstances, and not by reference to simple formulas, patterns, or stereotypes.

Profile-Based Risk Assessment Tools

Many who seek to reform California’s system of money bail and pretrial detention are turning to profile-based risk assessment tools. These take information about the accused, compare it to known behaviors of other people with similar characteristics, and generate a prediction about risk of future criminal conduct or missed court appearances. The predictions are statistical estimates based on a profile.

On the surface, these tools claim to avoid human biases and facilitate release of more people from pretrial detention, while promising rapid decision-making.

But these tools risk being a sophisticated form of racial profiling that produce biased outcomes because they ask questions implicating race, and because the underlying information evaluated, based on policing and law enforcement, reflects a system that is itself riddled with racial bias. If arrest and conviction data is racially biased, the tools that use this data to make decisions about who stays in jail and who gets released will generate racially biased outcomes.

The tools provide only statistical predictions based on non-contextual information and do not allow for explanation of prior criminal history. For example, a person who missed a court date because their return slip had the wrong day but came to court two days later would get the same negative score for failing to appear as someone who fled the country to avoid court. The profiles may miss specific, serious threats that do not appear on the surface of the criminal history, as someone with a minimal criminal record may represent an extreme danger in the given circumstances.

Despite the veneer of objectivity, the risk scores are subjectively defined and can be manipulated to direct fewer or greater numbers of people into custody or under supervision, depending on the needs of those administering the tools. For example, in Santa Cruz County, the tool was adjusted to double the number of people released under conditions of supervision.

While jail overcrowding provides incentive to use the tools to reduce pretrial detention, given the massive amount of jail construction going on in California, the tools may be used to increase detention in the future. A risk assessment tool can put people under increased levels of supervision or fill jails as easily as it can facilitate release.

Reform Requires Individualized Procedures

Instead of profiling and risk assessment by statistical prediction, or jailing people based on their wealth, California should adopt a system that favors release and assesses the risk of danger in an individualized, contextual way. As a default rule, only those accused of serious felonies should merit consideration for pretrial detention in the first place. The rest, with narrow exceptions, should be released from custody at the arrest stage and issued a citation requiring them to appear in court on a particular date. Cite and release would vastly reduce the number of people jailed without having charges filed against them.

The few who do stay in custody should have a full adversarial hearing, with an enforceable legal presumption of release absent proof by the prosecutor of a specific need to detain. Defendants should have capable legal representation when they get to court. The hearing should include testimony about the actual crime, so the judge can evaluate its seriousness and the likelihood of eventual conviction, an ability to pay hearing, and an opportunity to present individualized evidence favoring release or detention based on specific risk of pretrial harm.

This proposed system would involve significant changes in California courts’ approach to administering justice, and would be challenging to implement. But the advantages are essential. These changes would:

- Prioritize public safety by causing courts and prosecutors to focus on those defendants who truly pose a danger, while releasing those who do not.

- Decrease the harm suffered by families when their loved ones are jailed, and limit financial burdens placed on poor people who pay for their freedom.

- Mitigate the income-based discrimination of the current money bail system.

- Decrease the number of people, particularly innocent people, coerced into pleading guilty because of their custody status.

- Save the public money by cutting jail costs.

- Honor the presumption of innocence and treat people in court as human beings, not numbers.

Above all, it would increase the quality of justice in California.

Key Recommendations

- Expand legal requirements for law enforcement to cite and release without arrest to include all misdemeanor and all non-violent/non-serious felony suspects, with narrow exceptions, thus limiting the number of people placed in pretrial custody at all.

- Establish enforceable standards for setting bail or detaining pretrial, requiring release absent significant proof of a specific danger to the community or specific risk of evasion of court process.

- Establish procedures for meaningful hearings on pretrial detention and bail setting, including a testimonial probable cause determination and an ability to pay hearing, as well as opportunity to present mitigating and aggravating factors, while providing sufficient resources for appointed counsel to research, investigate, and conduct these hearings.

- Reject the use of statistical predictions of the likelihood of pretrial misconduct as a basis for or factor in setting bail or pretrial detention.

Methodology

This report is based on research conducted from September 2015-January 2017. Findings are based on 151 interviews.

Eighty-six interviews were with criminal justice professionals, including judges, district attorneys and other prosecutors, defense lawyers, including public defenders, probation officers and administrators, pretrial services personnel, academic experts, court administrators, policy analysts, law enforcement personnel, and court administration consultants.

Sixty-seven interviews were with people who had direct personal experience with pretrial detention in California as arrestees, prisoners, or immediate family members or partners of an arrestee or prisoner.

We also spoke to 21 attorneys and investigators who described the experiences of specific clients, and community organizers who work with people involved in the criminal system and their families.

The interviews in total cover experiences in 14 counties in the state. Just over 50 percent of the interviews of people with personal experience of being detained involved cases from Los Angeles County, as it is by far the county with the largest jail and court system. Berkeley Law students conducted 30 of the interviews contained in this report.

Of those who personally faced imprisonment pretrial whose stories we heard either directly or from a family member or an attorney, fifty-five were male and ten were female. Thirty-two were Latino, twenty-four were black, and nine were white. Some had significant criminal records; others did not. Some were convicted of some crime following their detention; many others were not.

Human Rights Watch identified people who had experiences with the pretrial detention system via several sources, including criminal defense attorneys who referred us to their former and current clients, and community organizations that work with people who have contact with the criminal system. Researchers spent time in court observing proceedings, including bail and detention hearings, and spoke to people they met in court.

Interviews were semi-structured and covered a range of topics, including description of the trajectory of the criminal case, efforts to pay bail, impact of detention on the individual and the family, impact of paying bail on the individual and the family, conditions of custody, and impact of custody status on the ability to contest the charges.

The interviews sought to determine if the pretrial detention system caused financial, physical, psychological, and/or penal harm. To the greatest extent possible, researchers reviewed court and attorney files, other court records, jail records, news accounts, and other independent sources of information to verify the case descriptions. Supporting documents are on file at Human Rights Watch.

Human Rights Watch uses pseudonyms for the individuals interviewed and their family members to respect their privacy, minimize the impact of revealing an encounter with the criminal system, including arrest or conviction, and to protect those who are vulnerable. Some of the people we spoke to are in jail or prison, on probation, or live on the streets where they may be subject to retaliation for speaking out about an injustice within the system. We have also disguised the names of lawyers who spoke about their clients to keep their clients’ identities hidden, and of criminal system professionals requesting anonymity so they could be more forthright in discussing the system and the actions or perspectives of colleagues and superiors.

All documents cited are publicly available or are on file with Human Rights Watch.

The Policy Advocacy Clinic at U.C. Berkeley School of Law provided outstanding assistance to Human Rights Watch on this report. Working under the supervision of Clinic Director Jeff Selbin and Teaching Fellow Stephanie Campos-Bui, law students Danica Rodarmel, Da Hae Kim and Mel Gonzalez prepared a background research memo about money bail and pretrial detention in California, nationally and internationally. The students compiled a list of suggested experts and other stakeholders in the California bail system, including judges, prosecutors, defense attorneys, law enforcement and non-profit organizations. After training from Human Rights Watch, the students conducted 30 of the interviews contained in this report.

To conduct data analysis for this report, Human Rights Watch requested data covering everyone booked into jail in 2014 and 2015 from every county in California. The responses from counties varied greatly as did the quality of the data provided. Many counties were unable to provide data at all, especially the smaller ones. In total, twenty counties throughout the state provided some sort of data. Different counties kept track of different things, and tracked similar things differently. For example, some counties carefully tracked bail amounts, while others did not. Some counties changed bail amounts to zero when the prisoner posted bond. For inclusion in the analyses, a county must have included data indicating whether there was a no bail hold flagged for each detainee. Otherwise, it is impossible to determine whether a detainee likely had bail set.

Each county provided descriptive “booking type” and “release reason” categorical variables using unique codes. Each county coded bookings and releases differently and no county could provide a manual detailing how specific types of bookings or releases should be coded by staff. Human Rights Watch recoded all booking and release types into new, coherent categories to our best ability, informed by conversations with sheriff’s department staff. Booking types typically fell into categories such as street arrests, en route bookings (bookings coming from or held for other jurisdictions), warrant bookings, parole or probation violations, or re-arrests. For each analysis in the report, notes indicate which types of bookings were included.

Counties provided information about all initial booking charges, and for some counties, conviction charges, per person. For counties that provided additional post-booking charges, only the initial booking charges were used. Offenses were coded as infractions, misdemeanors, non-serious felonies, and serious felonies, as defined in California Penal Code section 1192.7(c). The most serious crime for each person was identified by first ranking the charges by level of crime and then selecting the first crime listed in the database under the highest ranked level of crime.

Our analysis is limited by the data provided by counties, and therefore presents Human Rights Watch’s best estimates for describing jail bookings, bail, and releases in the counties included in the report. Those counties were selected because they provided data that contained enough variables and seemingly accurate data to provide estimates for specific research questions.

In addition to the county-level jail booking data, Human Rights Watch analyzed data from county bail schedules, the California Board of State and Community Corrections, the California Department of Justice, and the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ State Court Processing Statistics.

Pretrial detention, as with all aspects of the criminal system, is highly localized, with differences from county to county, courthouse to courthouse, and courtroom to courtroom. Surveying the practices of each of California’s 58 counties and of the hundreds of individual courtrooms is beyond the scope of this report.

I. Background

Pretrial Detention in the Context of Over-Incarceration

Pretrial detention in California, and throughout the country, is a significant part of a criminal system that incarcerates too many people, including people innocent of any crime; discriminates against racial minorities and poor people; and imprisons people for too long.

At the end of 2015:

- There were approximately 2,173,800 people in prisons and local jails throughout the United States.[1]

- The national rate of incarceration was 870 per 100,000 adults.[2]

- 6,741,000 adults were under correctional supervision, including parole and probation, a rate of 1 in every 37.[3]

These figures make the US the world leader in imprisonment, significantly outstripping overtly authoritarian countries like China, Russia, and Iran.[4] California had the second highest total number of prisoners in the country, behind only Texas, with 550,600 people under correctional supervision, including 201,000 in jail or prison.[5]

Rates of imprisonment increased dramatically from the late 1970s until just a few years ago,[6] though violent crime rates have fallen steadily since their peak in 1992, from 1,055.3 per 100,000 to 426.4 per 100,000 in 2015.[7]

The racial and economic class dimensions are inescapable. The incarceration rate for white people, based on 2010 census data, is 450 per 100,000; 831 per 100,000 for Latino people; and 2,306 per 100,000 for black people.[8] The same study revealed a rate of 3,036 per 100,000 for black people in California, compared with 453 per 100,000 for white people.[9]

Nationally, prisoners overwhelmingly come from the poorest economic class. One study showed the median pre-incarceration income for all male prisoners was 52 percent less than the median income of non-incarcerated men. The rate for incarcerated women was 42 percent less.[10]

As rates of imprisonment have increased dramatically, so too has the practice of pretrial detention. Nationally, from 1990 to 2009, the use of money bail increased from 37-61 percent.[11] During this time, the percentage of people detained pretrial grew considerably.[12]

Pretrial Detention in California

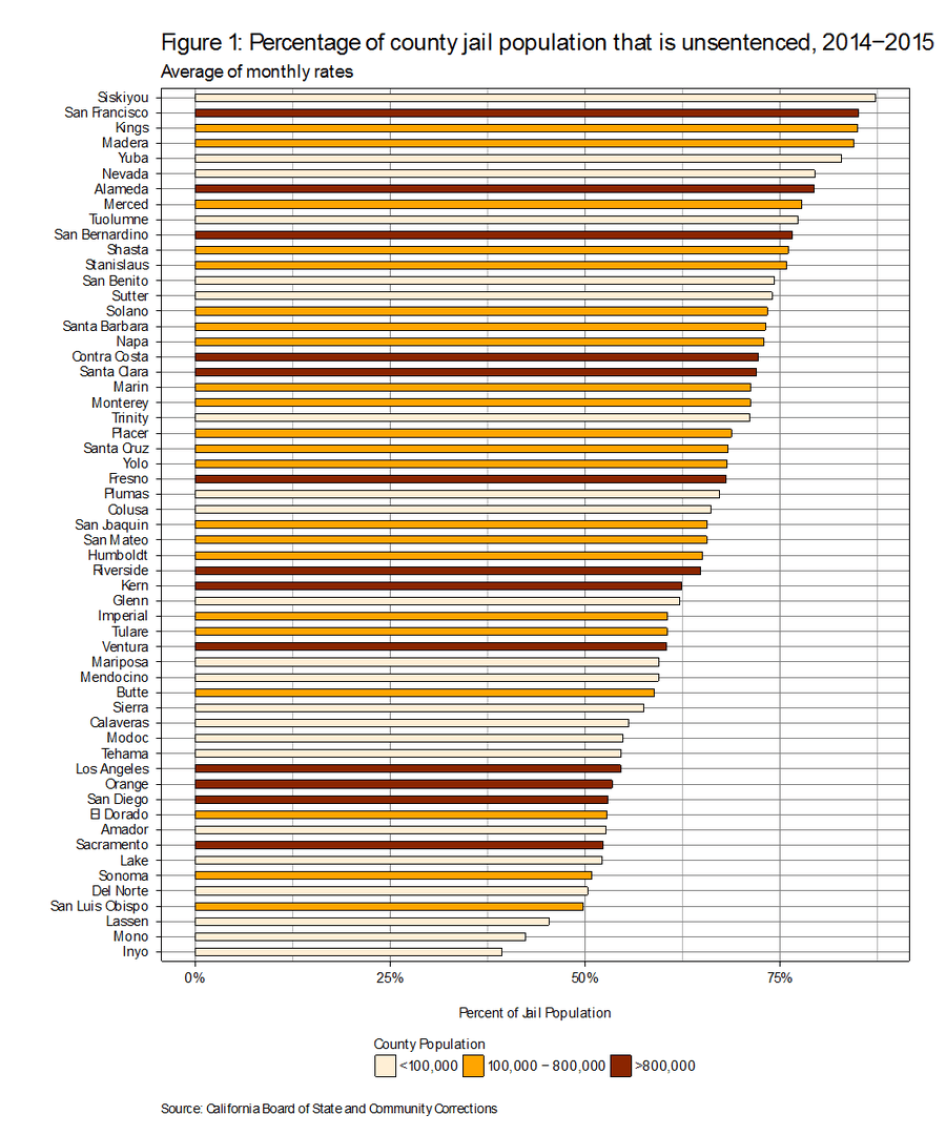

California counties detain pretrial at a far higher rate than the rest of the country.[13] In recent years, around 63 percent of prisoners in California jails have not been convicted or pled guilty.[14]

As with nearly all aspects of the criminal system, these figures are subject to local variations among counties. Inyo, for example has a pretrial detention rate of just less than 40 percent, while Siskiyou’s rate is 87 percent. Of the larger counties, Los Angeles and Sacramento’s rates are just over 50 percent; Alameda, San Bernardino, and San Francisco’s are over 75 percent; and Riverside and Santa Clara’s rates are in the high 60s-low 70s percent range.[15]

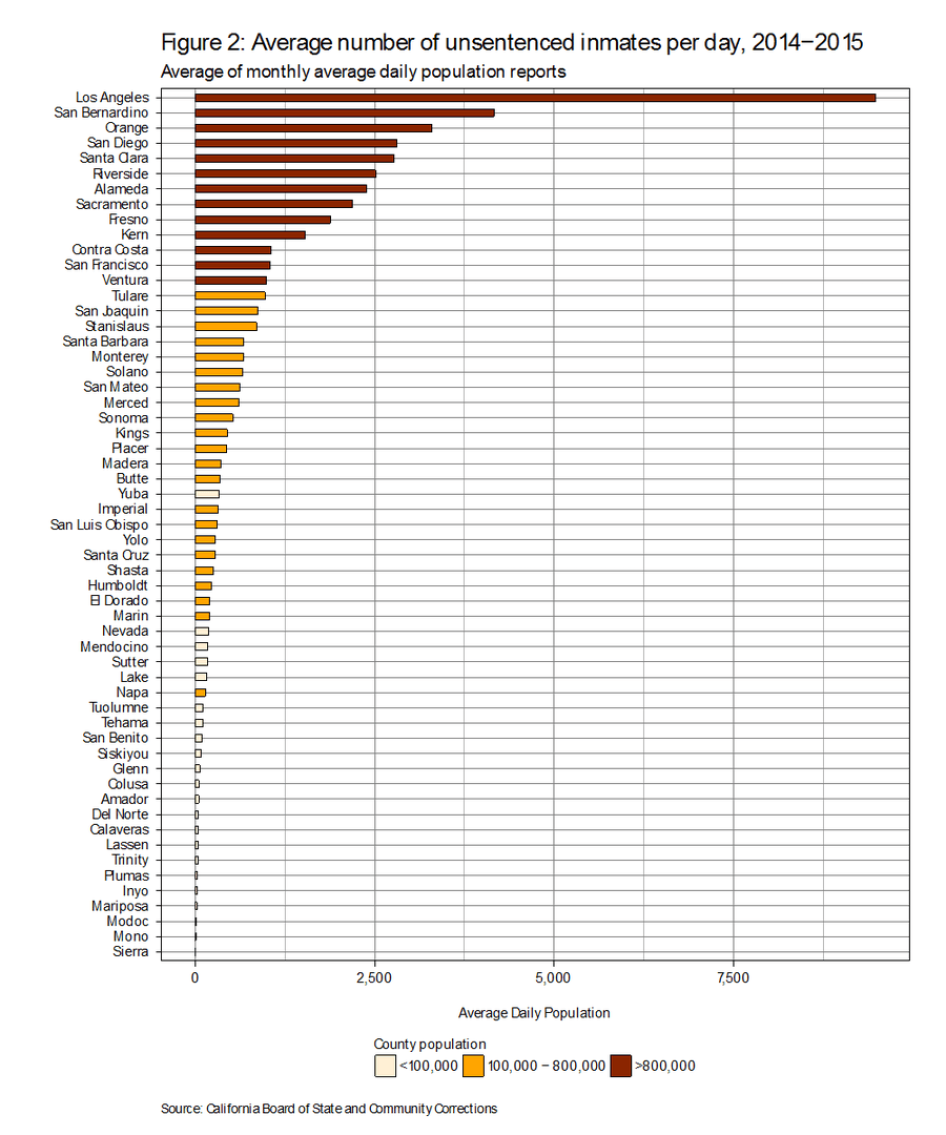

The total numbers of people detained pretrial in California at any given point in time varies, ranging between 52,000 and 42,000 from January 2014-January 2016.[16] Jails range from having a small number of pretrial prisoners, to housing thousands.[17]

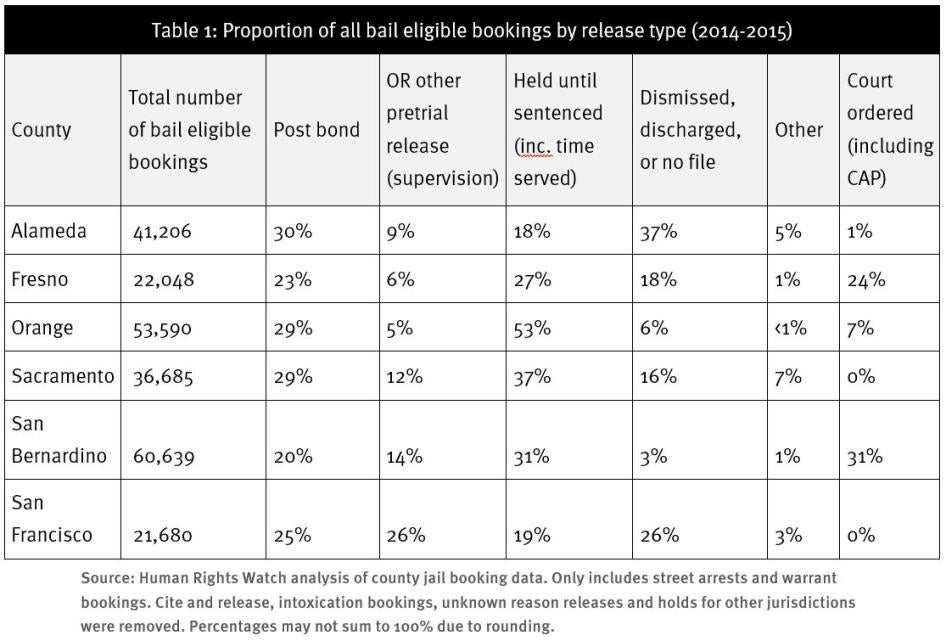

Human Rights Watch analysis of data from six California counties (see Table 1, below) finds that just 20-30 percent of bail eligible prisoners ended up posting bond. The failure to post bond comes at a cost to California’s taxpayers: In Sacramento County, the cost of detaining people who were bail-eligible but who did not pay bail was over $44.3 million

from 2014-2015.[18]

There were wide differences between counties in how prisoners who did not post bond were ultimately released from jail:

- People jailed in San Francisco County were more regularly released on their own recognizance or under other pretrial release programs;

- Orange County released very few people on their own recognizance or under other pretrial release programs;

- In Alameda County, nearly 40 percent of people booked into jail remained in custody until dismissal or were released with no charges filed;

- In San Bernardino County, one of every three people booked into jail was released due to court orders to reduce the jail population;

- In Orange and Sacramento Counties, higher percentages stayed in custody until their sentences were complete.

In each county analyzed, black people were booked into jails at a much higher rate than white people. In San Francisco County, the ratio was nine to one, when controlling for population size. Because of the high rates of black people booked into custody, the problems of the bail system have a disproportionate impact and contribute to racial bias in the overall criminal system.

II. Pretrial Detention in California

Pretrial Detention Process

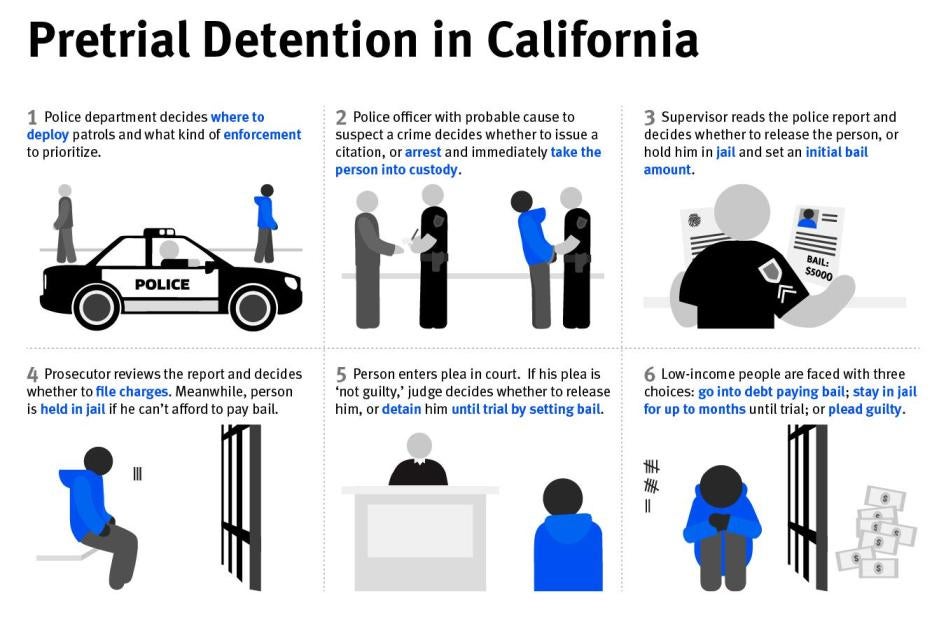

Different authorities use their discretion, guided by certain rules, to make crucial pretrial custody decisions at a series of distinct stages in California’s criminal justice system.

The police officer in the field decides whether to arrest or simply issue a citation; the supervisor at the station decides whether or not to set a bail; the prosecutor decides to file, reject, or delay the case; the prosecutor in court decides to request bail or agree to own recognizance release; and the judge decides what amount of bail to set. Additionally, the accused is sometimes able to make a decision whether or not to pay the bail―depending on wealth, family and community support, and willingness to make other financial sacrifices. Finally, the bail bondsman decides whether or not to offer terms that the accused and their family or supporters can meet.

Step One: Police Deployment and Enforcement Choices

One set of crucial decisions made long before anyone is arrested relates to police deployment. Police departments have limited resources and make choices about where to concentrate patrols and what enforcement priorities to emphasize. These choices, in an aggregate sense, determine who gets arrested and with what frequency.

Nathan Ramos lived in an encampment of homeless people in the Skid Row section of downtown Los Angeles.[19] Because the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) had chosen to deploy large numbers of officers to the area to enforce “quality of life” crimes, like sleeping on the sidewalk, Ramos had frequent contacts with officers.

In early 2012, officers arrested him for having his tent on the sidewalk. They took him to the Central Station lock-up and booked him, ignoring his requests for medical attention, and placed him in a holding cell with just a concrete bench, a sink, and a toilet, for over twelve hours. He received no food while there. Eventually they moved him to the main LAPD jail where they put him in a cell that felt “like an ice box.”[20] After two days in custody, police moved Ramos to the lock-up at the 77th Street Station, and released him a day later. The prosecutor never filed charges against him.

Step Two: Police Decide to Arrest or Release

A police officer with probable cause to believe someone has committed a crime, through observation or witness report, has authority to arrest.[21] Police may arrest at the request of a private person,[22] and may also use their discretion to issue a warning for certain violations.

For misdemeanor violations, California Penal Code section 853.6 requires police to issue a citation, with a signed promise to appear in court, and release the person without arrest.[23] This rule exempts certain stalking, domestic violence, and restraining order violations.[24] However, the law also allows a series of general exceptions that give police officers nearly unlimited discretion to arrest instead of release.[25]

The exceptions include permitting arrest if: “prosecution of the offense … would be jeopardized by immediate release of the person arrested”; “there was a reasonable likelihood that the offense or offenses would continue or resume, or that the safety of persons or property would be imminently endangered by release”; or “there is reason to believe that the person would not appear at the time and place specified in the notice.”[26]

While these provisions sound appropriate, they are vague, set no standard or oversight for the reasonableness of the officer’s determination, and are open to interpretation. In practice, officers can always articulate some reason to believe the crime will resume or the suspect is dangerous or will not appear in court. In practice, Penal Code section 853.6 barely constrains officers from arresting people on misdemeanor charges, instead of citing them with a signed promise to appear.

If the officer decides to cite and release, the suspect signs a “promise to appear,” and receives a ticket with the court date, time and location, and the nature of the charges. The person receiving the ticket must appear in court to face the charges, or the judge will issue a “bench warrant,” authorizing subsequent arrest. If an officer detains someone and determines they have an outstanding warrant, the officer retains the discretion to arrest, issue a separate citation to appear on the warrant, or simply give the person a warning.[27]

People who are cited usually remain out of custody throughout the pretrial period, while those who are arrested and remain in custody have a much greater chance of having a bail set.[28] The initial decision to make the arrest instead of cite and release can have profound consequences for those arrested and their families.

|

Michelle Roberts’ boyfriend was arrested for driving under the influence of alcohol.[29] The officer took him to the station for a breathalyzer test, where he blew .081, just over the legal limit.[30] Instead of giving him a citation and allowing him to call Michelle or a cab for a ride home, the officer chose to book him into the Santa Rosa City Jail. Given his low blood alcohol concentration, the officer could not justify refusing release based on intoxication.[31] It does not appear that any of the other exemptions in Penal Code section 853.6 reasonably should have applied. Still, he remained in jail. Michelle had to contact a bondsman and pay a $500 non-refundable premium to get her boyfriend released. He vowed to pay her back, but had financial troubles. The debt, Michelle said, was a “weight” on the relationship, which ended soon afterward. In this case, the officer had a legal reason to cite and release, but chose not to, although other officers may have used their discretion differently. |

There is no presumption in favor of citation and release in felony offenses. Police must arrest all felony suspects, whether or not they are dangerous or likely to go to court.

Step Three: Police Station Officers Decision to Set Bail

When police arrest a suspect, they put him or her through the booking process at the station, including taking photographs and fingerprints, checking for outstanding warrants, and filling out various forms. The arresting officer prepares a report describing the offense, including any evidence, witness statements and contact information, and statements by the accused.[32] The officer’s supervisor must review the report and determine whether it describes conduct amounting to a crime and what the crime is.

If the supervisor determines there is no crime or that further investigation is needed to come to a conclusion, they release the arrestee.[33] If the supervisor determines there is a crime, they have discretion to release after booking or to detain until the first court appearance. Each county has its own policies governing jail releases.[34] For misdemeanors, Penal Code section 853.6 sets a presumption in favor of release; however, as with the officer in the field, the in-station supervisor has wide discretion to keep the accused in custody.

Penal Code section 1269b(a) authorizes the officer in charge of the jail to set an initial bail amount for an arrestee held in the jail immediately after booking. The officer sets bail according to the county’s bail schedule, which has a standardized amount based on the charge.[35] The arrestee may then post the bail by depositing money at the jail.[36]

Some counties have judicial officers on duty who will review each arrest and decide whether to order the arrestee released on a promise to appear or to set bail. In Santa Clara County, for example, a magistrate automatically assesses the arrestee’s suitability for own recognizance release.[37]

In Los Angeles County, a government official told Human Rights Watch that a bench officer is assigned to review requests for own recognizance release pre-arraignment.[38] Prisoners call a division within the probation department to request release, which provides a brief evaluation of the prisoner for the on-duty judge. Only one judge reviews applications at any given time. According to the official, the duty judges are generally inexperienced and have little information on which to base decisions, are risk adverse, and do not hear from any advocates in this process.[39]

Step Four: Prosecutor’s Decision to File Criminal Charges

After an arrest, the police officer submits their report to the prosecutor for filing consideration. The prosecutor reviews the report and may reject the case outright, file a different or reduced charge, file the charge recommended by the police, or request further investigation.[40] If the accused is in custody, the prosecutor has 48 hours to file the case from the time of arrest, excluding weekends and holidays.[41] People arrested on Thursdays and Fridays usually spend the weekend in jail before seeing a judge.

Often people will sit in custody, only to be released with no filing. In May 2011, police arrested Jose Alvarez after he participated in a protest at Los Angeles City Hall and accused him of a felony.[42] They booked him at the station and set a bail he could not afford. He did not have money to pay for his release and sat in a police station cell from Friday afternoon until the following Tuesday morning, when they took him to court. Alvarez sat in a crowded holding cell all morning before the deputy district attorney notified his lawyer they were not filing charges. It took them until late evening to process his release and let him go.

Step Five: Setting Bail in Court

If the prosecutor does file charges, the arrested person must appear in court. At the first court appearance, called the arraignment, the accused is assigned an appointed lawyer if they do not hire their own; receives the complaint, which details the charges; and receives the crime report and a copy of their rap sheet.[43] The accused enters a plea, generally after consulting their lawyer and sometimes after evaluation of a settlement offer.[44]

After the accused enters a “not guilty” plea, the judge addresses pretrial detention. If the accused seeks an own recognizance release, their attorney will make the request. If the prosecutor wants a bail set, they will ask the judge to do so. Often the arresting officer or prosecutor will fill out a bail request attached to the complaint submitted to the court.

After the request for bail or own recognizance release, the judge conducts a hearing and decides. The judge may release the accused, with or without conditions, or set a bail. Release conditions that a judge may impose due to concern for public safety or to ensure appearance in court may include requirements to “stay away” from a person or location, attend Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, submit to house arrest, or electronic monitoring.[45] If an individual fails to adhere to these release conditions, a warrant will be issued for their arrest.

Usually, if a person appears in court in response to a citation or a summons, the judge will continue the own recognizance release. The judge may also set bail, usually in accordance with the set bail schedule.

Step Six: Obtaining Bail

If the judge sets bail, the prisoner must decide whether to pay for their release. For many, the decision is simple—the bail is too high.[46] For a homeless person living on General Relief in Los Angeles County,[47] even a bail of a couple hundred dollars is out of reach.[48]

A person who can afford to pay full bail deposits it with the court clerk or law enforcement[49] and immediately secures the prisoner’s release. Assuming the accused returns to court and does not miss future appearances, the person who put up the money will get it all back once the case is resolved and the bond exonerated.[50] However, few people pay the full amount.[51]

Those who cannot pay the full amount may use a bondsman, who charges up to a 10 percent fee and puts up a bond promising to pay the full bail amount if the defendant does not appear in court. The fee is not refundable, regardless of the case’s outcome.[52]

|

Katherine Gibson’s Case Katherine Gibson had some drinks with friends after work one Sunday afternoon, then had a minor traffic collision while driving home.[53] Police arrested her, took her to the station, took a blood sample, and booked her into custody. Katherine had never been in trouble with the law. In her mid-twenties, she had recently moved to Los Angeles from a mid-Western town and set up a small business caring for and walking dogs. But she had begun to have health problems, including a wrist injury and a cancer diagnosis, and she took medications for anxiety. At the station, handcuffed to her seat, Katherine heard officers making crass comments about another female arrestee. Eventually, they put her in a filthy holding cell, where she sat for several hours on a concrete bench. She was then moved to another cell with bunks and an exposed toilet, which flooded during the night. Terrified of the police and her fellow prisoners, in pain and missing essential medical treatment, Katherine had an anxiety attack, hyperventilating and yelling for help. Usually, a first time driving under the influence charge results in release from custody after no more than a few hours to get sober and a citation to appear in court.[54] Even a guilty plea for a first offense driving under the influence almost invariably involves probation[55] and a fine, but no jail time. But the police would not release Katherine. They set a bail of $100,000.[56] At the first opportunity, Katherine called her father for help. He called bondsmen, who offered to post the bail in return for a non-refundable 10 percent fee. Her father did not have the money, but was able to borrow it from a relative. At 9 p.m. Monday night, police released her with an order to appear in court to answer to felony driving under the influence charges. Katherine had no prior convictions,[57] and there was no evidence anyone was injured badly enough to merit the more serious charge.[58] But the arresting officer had characterized the violation as a felony in his report, so station officers assigned the felony bail level. Had the officer not called it a felony, Katherine would likely have been cited out on her own recognizance, or would have had to pay a $2,000 fee to the bondsman, not $10,000.[59] “I know I messed up. I know there should be consequences,” Katherine said. But she feels she was set up to fail. The experience has left her discouraged: “I can completely understand why people can’t get out of the system.”[60] On her court date, Katherine learned the district attorney did not file the felony and that she faced a misdemeanor charge. Despite the reduced charge, Katherine could not get her money back from the bondsman. She wanted to fight the case, but did not have enough money to pay her lawyer to go to trial. So she pled guilty for probation, a fine, community service, and classes. She now cannot afford car insurance, limiting her ability to work, and struggles to pay rent. |

How Judges Set Bail

Fixing bail is a serious exercise of judicial discretion that is often done in haste … without the full inquiry and consideration which the matter deserves.

—Stack v. Boyle, 342 U.S. 1, 11 (1951) (J. Jackson, concurring opinion)

Bail Hearings

Hearings to decide pretrial release status and to set bail amounts in California are generally extremely fast and often involve minimal argument. Judges have imprecise guidelines to direct their discretion, and almost no meaningful oversight. A defendant is entitled to review the bail order within five days,[61] but the practical likelihood of changing the original judge’s decision is very small. The original judge who set bail at arraignment sometimes conducts the review.

In setting bail or granting release, the judge engages in an assessment of risk—primarily related to community safety.[62] They also assess the probability of the defendant not appearing in court.[63] In doing so, the judge considers the seriousness of the charged offense, the defendant’s prior criminal history, and prior missed court dates.[64] The judge may consider mitigating factors about the defendant, including work and schooling, ties to the community, and other factors that counsel may present to the court.

The judge evaluates the seriousness of the offense based on reading the police report; there is no evidentiary hearing with live testimony about what really happened. Counsel may, but often does not, have the time or resources to present additional argument, based on statements, declarations, letters, documents, and representations.

A public defender who handles a high volume of arraignments and/or bail hearings in one Southern California court described having a short time to talk to the prisoner, review the facts of the case, get some mitigating information about employment and community ties, make calls to verify the information, then argue for release or low bail in court.[65] He said that if he had a paralegal or investigator or more attorney assistance at this stage of the case, he would have more success securing release for his clients.

Common court practice is not to put great effort into bail hearings. In Alameda County courts, there is often no attorney appointed for the initial bail hearing.[66] One Los Angeles County Superior Court judge has criticized public defenders for not fighting to get their clients out of jail at arraignment.[67] According to retired San Diego County Judge Lisa Foster:

To be perfectly honest, I didn’t think much about bail, and to the best of my recollection, neither did anyone else—not my colleagues on the bench, not the prosecutors, not the public defenders.[68]

Another Los Angeles County judge observed lawyers do not strenuously litigate bail, and that high bail is a part of court culture.[69] One reason defense lawyers cite for not fighting bail hearings more strenuously, in addition to lacking time and resources to make effective presentations, is that judges tend to avoid making individualized decisions by automatically applying the bail schedule amount based on the charge.[70]

California Bail Schedules Mean High Bail

The bail schedule is a list of crimes or categories of crimes, each with an amount of bail fixed.[71] The schedules add amounts for alleged prior offenses and enhancements.[72]

Each California county sets its own bail schedule according to its own procedures.[73] Usually, the judges meet annually to prepare, adapt, and revise a uniform schedule for all crimes.[74] The law gives no guidance beyond commanding them to consider the seriousness of the charge.[75] One judge from Contra Costa County acknowledged that judges did not base their bail schedule decisions on actual data.[76] The public defender from Contra Costa County, who sends a representative to the judges’ meeting to set the schedules, said bail amounts had “no correlation to public safety or the risk of failure to return to court. They appear to be pulled out of thin air.”[77] A Central California judge who was on his county’s bail schedule committee described receiving a circulated copy of the schedule, reviewing it for a few minutes, then voting to approve it.[78]

Bail schedules vary drastically from county to county, without apparent correlation to crime rates, income levels, or even regional preferences.[79] Though the bail levels may differ by county, overall, they are extremely high.[80] The median bail amount in California ($50,000) is over five times that of the rest of the country.[81] Overall bail levels increased in California by an average of 22 percent from 2003-2013, though some individual counties have reduced their bail levels.[82]

The stated purpose of the bail schedule is to provide a bail amount for law enforcement officers to set after booking an arrestee and determining not to release that person with a citation.[83] The judge is supposed to make an individualized decision about the amount once the defendant comes to court, and only needs to justify departing from the schedule if the offense is a “serious” or “violent” felony or for certain other specified offenses.[84]

However, despite the high levels of bail proscribed by the schedules and the lack of careful planning in creating those schedules, judges across the state tend to use them reflexively instead of making an individualized decision.[85]

Contra Costa County Chief Public Defender Robin Lipetzky told the Little Hoover Commission Regarding Bail Reform and Pretrial Detention:

Unfortunately, what I have seen in Contra Costa is that judges are loath to deviate from the bail schedule regardless of circumstances of the individual charged. In essence, the preset bail schedule has become a presumptive bail for each and every defendant. Blind adherence to a bail schedule has become the default; it is expedient, it requires no independent thought, and it provides easy cover for judges….[86]

Judge Eskin of Santa Barbara County echoed Lipetzky’s assessment, saying that judges set bail on schedule because it is easy and expedient, as they only have a few minutes per case, and using the schedule facilitates getting through the calendar.[87]

The American Bar Association condemns the use of bail schedules, calling them “arbitrary and inflexible” and warns they “inevitably lead to detention of people who pose little danger of re-offending or not appearing in court, while facilitating the release of wealthy dangerous people.”[88]

Many judges prefer the bright line rules that the bail schedules provide.[89] Some are concerned they will be blamed if they release someone from custody with a low bail, and that person commits a future crime;[90] many prefer defendants to be in custody. Using the bail schedule allows judges a quick method of setting bail levels high enough to keep most people in custody without appearing to be especially harsh.

Judges’ deference to bail schedules concentrates power in the hands of prosecutors, who can dictate the amount of bail by what charges they choose to file and how many counts and enhancements they add.

One San Francisco judge related the story of a defendant arrested for statutory rape,[91] an offense punishable as a misdemeanor or a felony. The district attorney filed it as a misdemeanor; the judge set bail pursuant to the misdemeanor bail schedule. The defendant’s boss paid for his bond. After he bailed out, the prosecutor re-filed the case as a felony and requested an increase to the felony bail schedule level. This judge noted that the conduct was no different, nor was the danger to the public and risk of failure to appear, and so refused to increase bail.[92] Other judges may have acquiesced.

Not surprisingly, prosecutors tend to strongly support the use of bail schedules. Alameda County District Attorney Nancy O’Malley told Human Rights Watch that she saw them as a good starting point, though noted prosecutors can ask for increases.[93] Los Angeles County District Attorney Jackie Lacey said that she liked the “consistency” that bail schedules provide.[94] Deputy District Attorney Larry Droeger, representing the Los Angeles County District Attorney’s office at a meeting on Los Angeles County bail reform, expressed his office’s support for using schedules, as they tie the bail amount to the seriousness of the crime and, as a practical risk assessment tool, they believe the schedules work.[95]

The director of pretrial services for one Central California county disagreed with Droeger’s premise, warning it is a mistake to equate risk with the seriousness of the charge.[96]

Daria Morrison’s case provides a good example of the charge not correlating to the actual risk level.[97] Prosecutors charged her with three counts of robbery, and the judge set bail at the scheduled amount of $150,000. The judge did not account for her lack of any criminal record, her role as caretaker for her mother, or that she was working two jobs and going to school. The court eventually heard the evidence during the preliminary hearing, and learned that she had been a passenger in the car and not involved in the robbery itself. She ultimately pled to a much-reduced charge with a community service punishment, but not until her family went into debt paying her bail.

One analyst has determined that lowering bail schedules by 10 percent would reduce the percentage of pretrial detainees by 4 percent.[98] The unaffordable bail amounts in the current schedules keep large percentages of people in what essentially amounts to preventive detention.

Preventive Detention

Preventive detention means holding a defendant in custody pretrial without any opportunity for release, and prevents the accused from absconding or being a danger to the community.

The California Constitution makes preventive detention extremely rare. Article 1, Section 12 guarantees all defendants the right to pretrial release “on bail by sufficient sureties,” unless they are accused of a capital crime, a violent crime, or felony sexual assault when there is “clear and convincing” evidence that their release will entail a substantial likelihood of serious injury to another person, or any felony when there is “clear and convincing” evidence the defendant threatened to cause serious injury to another and is likely to carry out that threat. Before ordering “no bail” or preventive detention, the judge must find “the facts are evident or the presumption great” that the accused is guilty.[99]

However, judges can and often do avoid the constitutional requirements of formal preventive detention by simply setting a bail amount too high for the accused to pay. Chief Justice of the California Supreme Court Tani Cantil-Sakauye told Human Rights Watch that imposing bail results in preventive detention.[100]

Several other judges also acknowledged this.[101] A former Santa Barbara County judge said, “We set bail at an amount to keep the defendant in jail.”[102] A pretrial services official for a Central California county told Human Rights Watch that a judge from Fresno told him that he used bail as preventive detention.[103] When a judge follows the schedule and sets a $5,000 bail for a homeless person, he knows he may as well have ordered a “no bail” detention.

At least one California appellate decision has said: “… [T]he Court may neither deny bail nor set it in a sum that is the functional equivalent of no bail.”[104] This statement may not have the practical force of law.[105] Though some judges may account for a defendant’s ability to pay,[106] most refuse to consider it.[107] Some judges have an understanding of a defendant’s ability to pay, and deliberately set bail above that. While the California and Federal constitutions forbid “excessive” bail, neither require affordable bail.[108]

Of course, using bail as a replacement for preventive detention does not necessarily advance the cause of public safety, as some released people may commit new crimes regardless of socioeconomic status.[109]

|

Bail bond industry representatives describe money bail as “a liberty-promoting institution” and cite its ability to allow defendants freedom without major costs to taxpayers.[110] But it can involve significant costs and financial harm to defendants and their families. Fees paid to bail bondsmen are not refunded regardless of the outcome of the case. After bail is set at the police station or in court, defendants or their supporters may go to bondsmen who then decide whether to accept the bond. Bondsmen look at a variety of risk factors about the accused to decide if they should insure the appearance.[111] One crucial factor they look at is how much money the defendant can pay toward the fee. An employee of Bail Hotline in Sacramento said charging fees is done “case by case”: Technically, we have a guideline but we just sort of work everything out based on who we are dealing with. Usually, we ask for 10 percent of the bail amount up front, but we have discretion in setting that up. Our goal is to try to get as much payment up front as possible.[112] Competition among different bond agencies means they will often make deals, including reducing their fee to 8 percent, sometimes lower.[113] They frequently offer payment plans, sometimes agreeing to down payments as low as 1 percent, along with monthly payments. Matthew Dixon told Human Rights Watch he spent a week in the Alameda County Jail with a $180,000 bail set before a friend could find a deal from a bondsman.[114] His friend paid $1,500 up front on a $15,000 premium, and Matthew now pays $250 each month to the bondsman, who constantly pressures him to make payments. Paul Fowler described how his son was arrested and held in Contra Costa County Jail with a $250,000 bail before his court appearance.[115] The bondsman pressured him to pay immediately in case the prosecutor added more charges. Fowler waited. At the arraignment, the judge reduced the bail to $30,000. He paid $1,500 down and set up $300 per month payments on a $3,000 premium. The American Bar Association, recommending abolition of for-profit bail bonding, decried this discretion in the hands of private, minimally regulated, profit-motivated actors: It is the bondsmen who decide which defendants will be acceptable risks—based to a large extent on the defendant’s ability to pay the required fee and post the necessary collateral.… [D]ecisions of bondsmen … are made in secret, without any record of the reasons for these decisions.[116] Several people whom Human Rights Watch interviewed complained about bail bondsmen taking advantage of their lack of knowledge of the system to get them to pay, or otherwise manipulating them.[117] One person described how a bondsman convinced her mother, diagnosed with a mental illness, to pay a non-refundable fee, when the daughter could have deposited the full bail amount.[118] Hutch Harutyunyan, of Gotham Bail Bonds, said that, by contract, bondsmen have earned their fees when police release the prisoner.[119] If the case does not get filed, the person paying the fee still owes the money under any agreed upon payment plan. If the prosecutor decides to file the case at some future date, after the court has exonerated the original bond,[120] and the judge sets a new bail, the defendant must pay a completely new fee to obtain bail. Kevin Ocampo in Alameda County paid a 6 percent fee on a $250,000 bail to get his cousin out of jail.[121] When he went to court, the judge raised the bail to $325,000. The bondsman would not apply the amount already paid to the new bond. Instead, Kevin had to pay a new premium of 8 percent on the new amount. Henry Anderson said he paid a fee to a bondsman.[122] He went to court, and his case was dismissed. The district attorney later re-filed the charges, the court set a new bail, and Anderson had to pay a whole new fee to secure his release. The US and the Philippines are the only countries in the world with private, for-profit bail bond industries.[123] Many other countries and some states use financial bail, but require payment directly to a government agency. In Illinois, defendants pay 10 percent of the bail directly to the court clerk. If they make their court dates, the clerk returns their money minus a maximum $100 processing fee.[124] The disadvantage of this type of system for people seeking pretrial release is that they must pay the full 10 percent amount up front. Bondsmen in California allow many people to buy freedom with a low down-payment and installments when they might otherwise not be able to pay. Daria Morrison is still making payments on the bond her father got for her after she spent three weeks in jail on a robbery charge in Los Angeles County, though she is grateful to the bondsman for helping her out of jail.[125] |

II. Bail Leads to Jailing People Who Are Not Guilty

One of the most harmful aspects of California’s bail system is that it results in the pretrial incarceration of hundreds of thousands of people without proof they committed any crime.

From 2011-2015, police in California made 1,451,441 felony arrests of individuals, all but a small fraction of whom had bail set for some period of time. Of those, 459,847 were arrested and held in jail, but never found guilty of any crime.[126] Prosecutors did not even file charges against 273,899 of those people.

In other words, over a quarter-of-a million Californians sat in jail for up to five days, accused of felonies for which evidence was so lacking prosecutors could not bring a case.

The others had cases filed, but lacked sufficient proof of guilt, resulting in eventual dismissal or acquittal after weeks and months in jail. Many of these people were victims of baseless arrests; others, mistakes of judgment, or misunderstandings of the law.

These people spent days, weeks, and months in jail while waiting for trial, serving out sentences for crimes they did not commit, losing jobs, missing their families, having to drop out of school, suffering the misery of being locked up. By setting bail that people

cannot afford, the pretrial detention system punishes people without proving their guilt.

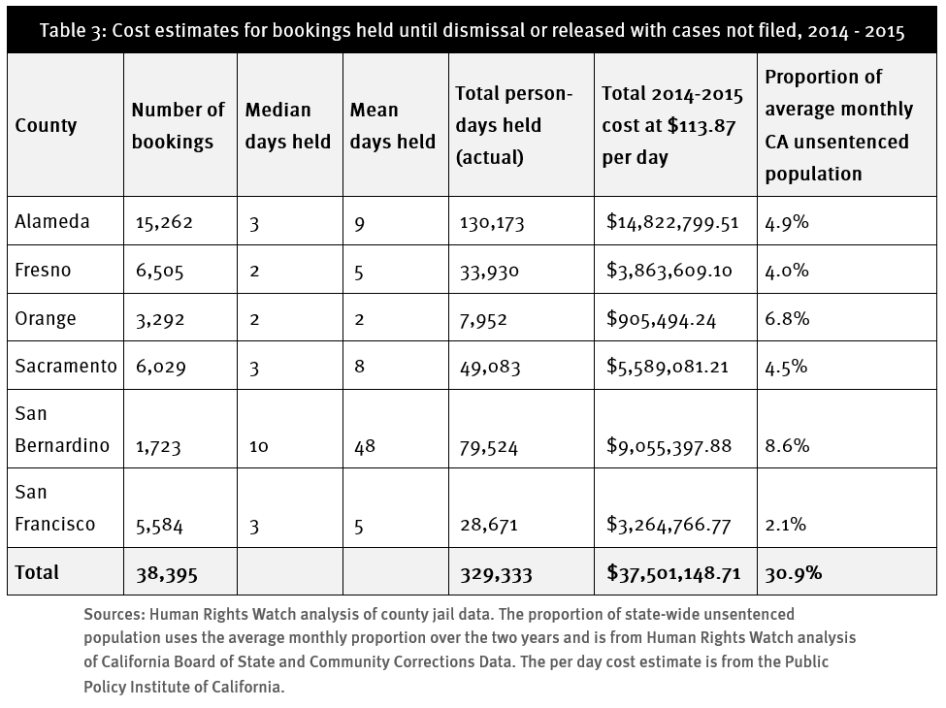

The cost to taxpayers of this senseless pretrial punishment is staggering. Each day a person is held in custody costs an average of $113.87.[127] Human Rights Watch analyzed all bookings into jails in Alameda, Fresno, Orange, Sacramento, San Francisco, and San Bernardino Counties for 2014 and 2015.[128] The total cost of jailing people, never found guilty of any crime, just in these counties, was about $37.5 million over the two years.

***

|

Bail Keeps People in Jail After Arrest without Basis

Jason Miller is in his mid-forties and lives on the streets in the Skid Row section of downtown Los Angeles.[130] Because of his homeless status, and because the Los Angeles Police Department saturates the neighborhood with officers, he has had many encounters with police in recent years. He has been off probation since 2013, but counts 10-15 arrests since then. As he has no money to pay bail, his arrests mean he goes to jail. In the summer of 2016, Jason told Human Rights Watch he and an officer had an argument about his dog. Jason demanded to speak to a sergeant, but instead, a lieutenant came and ordered the officers to arrest him. The reason they gave: he possessed narcotics.[131] They took him to the police station, booked him, and held him under the felony bail schedule amount of $10,000. Jason told Human Rights Watch he had not possessed drugs, but he had no money to get out. He stayed in the station jail, unable to sleep due to the noise, with no books, television, or anyone to talk to. On the third day, he went to court where he was packed into a cell with close to 40 other prisoners, many of whom were starting fights. Finally, at about 4:30 p.m., deputies at the lock-up told him the case was a DA reject—no filing. It took him two more days and $122 to get his dog out of the pound. All his property, including tent, clothing, toiletries, and medications were gone. |

|

Jailing People Who Are Not Guilty David Gonzalez, 19, was looking forward to going to college in the fall.[132] He had just graduated from high school, lined up his classes for August at Santa Ana College, and was looking for a job when police arrested him and locked him up in the Orange County Jail. David told Human Rights Watch that the next day, July 7, 2016, police brought him to court for his arraignment. He learned he was accused of raping an unconscious person, a crime punishable by up to eight years in prison. The judge set bail at $100,000. David had had sex with the girl who had been raped, but had been away in school at the time of the alleged rape. Still, they took him back to jail where he would have to stay unless his family could get the money together. David’s father worked at a restaurant, making minimum wage. His siblings had no extra money. The family home was about to be foreclosed on, so they could not borrow money against the property. In jail, David tried to stay out of trouble. A couple of the older guys, seeing he was just a kid, looked out for him a bit and advised him to lay low. Still, he had a cellmate who gave him problems. He had to fight to protect himself a couple of times. Otherwise, there was nothing to do but sit and wait, and hope the truth would emerge. David’s sister Nina would miss work once a week to drive from San Bernardino to visit him and try to keep his spirits up. Still, he would break down in tears when she saw him. Nina was able to get his school records to help establish that he was in school that day. The case was based on DNA evidence, but the prosecutor had not spoken to the victim about David. Eventually, David’s lawyer located the victim. She confirmed that she had been with David the weekend before the rape, but he had nothing to do with the crime. On September 30, 2016, the prosecutor spoke to the victim and agreed to dismiss the case. David had spent nearly three months in jail for a crime he did not commit, because bail was so high his family could not afford to pay. He missed his first semester of college. |

Bail Keeps People in Jail Who Never Have Charges Filed

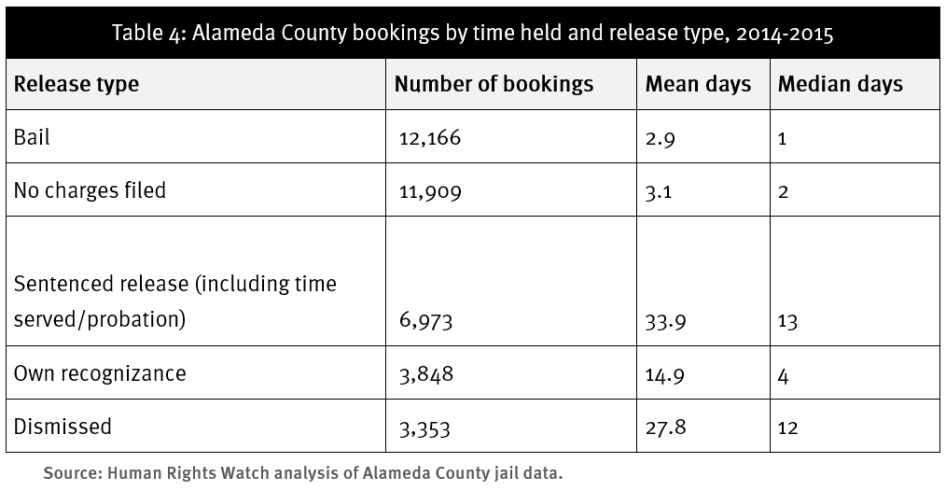

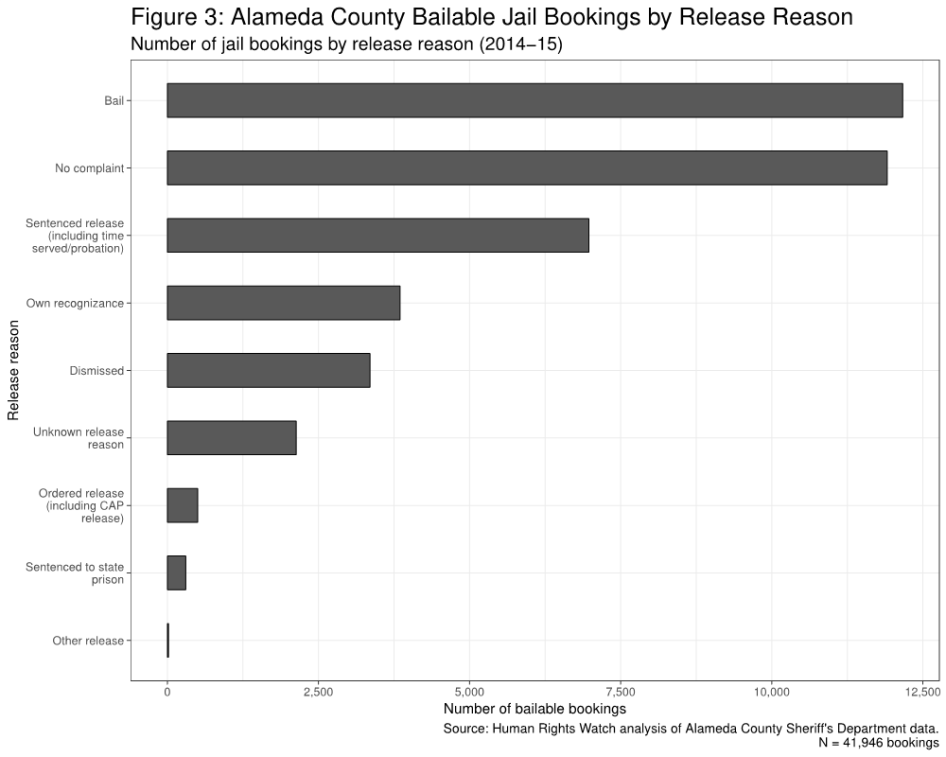

Human Rights Watch analyzed Alameda County 2014-2015 jail bookings and release data to determine how many people were released, under what circumstances, and how long they spent in custody.

The data reveals another 3,353 people whose cases were dismissed, but who still spent an average of 27.8 days in jail, probably costing the county more than $10.5 million.

The data shows a relatively small number of people given own recognizance release, but indicates it often took the courts a long time to come to that decision. Own recognizance release primarily occurred in the first week, but sometimes took weeks and months. 3,848 people were released this way, but they averaged 14.9 days in jail. Had they been cited and released by the arresting officer, the county would have saved around $6.5 million.

Of the 12,166 people who posted bond, most did so within the first day.

Figure 3 shows a very small number of police releases compared to “no filings.” This comparison raises a question about the judgment of police supervisors keeping people detained whose cases will not be filed. It points to the potential danger of a book and release program dependent on the station supervisor’s discretion as compared with a rule requiring cite and release instead of arrest for most cases.

Human Rights Watch similarly analyzed booking and release data from five other counties. Sacramento County, which jailed a similar number of people as Alameda County in 2014-2015, provides a comparison. In Sacramento, 5,094 people stayed in custody an average of 3.2 days with no charges filed. Sacramento booked and released about 19 percent of arrestees, over 10,000 people, within a day of arrest, likely reducing the number of “no filing” releases.[136]

- 10,459 people stayed in custody an average of 4.3 days before bailing out, though most were out in about a day. It is unclear how many of those who had to pay for their freedom ended up with no charges filed.

- 953 stayed in custody until their cases were dismissed or a jury acquitted them.

- 4,316 people were not cited out, but got own recognizance release orders from the judge. They stayed in custody an average of 8.2 days; the mean was 2 days.

- Just under 12,000 were released after finishing their sentence, spending an average of 25.4 days in custody.

While not as dramatic as Alameda County’s figures, data from Sacramento shows a substantial number of people in custody with no charges ever filed. Many of those arrestees whose cases did not result in filing had already paid non-refundable bail fees.

The CEO of San Francisco’s Pretrial Diversion Project, Will Leong, said that the district attorney in his county also rejects a large number of cases.[137]

Frank Robinson had a good job with the local transit service.[138] He was arrested in Alameda County on December 23, 2015, on a domestic violence warrant. The police set bail at $130,000. His mother co-signed for the bond and paid $1,000 with an agreement to make payments for the rest of the fee. He got out the next day. The prosecutor did not file criminal charges against him. Frank said:

And now that I am out of jail, I have to pay $200 a month to the bail bond agent. I don’t understand why I have to pay something when the charge was dropped. My family is stunned that this happened to me.[139]

Nancy Wilson described being arrested several times by Oakland police on drug related charges, borrowing money to pay bail, only to have no charges filed.[140] Brandon Watkins had a similar experience, also in Alameda County.[141] Police arrested him, claiming he had committed a battery.[142] They set a $15,000 bail. His parents went to a bond agent, paid $1,500, and secured his release. When Brandon went to court, he learned that there was no case filed against him.

India Fuller was arrested in Sonoma County when her son’s ex-girlfriend accused her of assault.[143] The police set a bail of $265,000. Various family members contributed to her bail fund, gathering $3,000 to give to the bondsman. India had been in jail for four days. The prosecutor dropped the charges, but she still pays $350 per month to the bondsman. She has fallen behind in her car payments. If she loses her car, she will lose her job as a driver.

Replacing arrests with non-custody citations would save police processing costs, reduce jail overcrowding, diminish the harms associated with even short periods of time in jail, like lost jobs and lost property, improve community relations with police, and limit police uses of force associated with “hands on” arrests.[144]

III. Bail and Jail Result in an Unfair Justice System

I’ve seen it. A time served offer on a custody defendant on a low-level charge, all they think about is, “Do I get out today? Can I get out today?” We have to take a look at whether we are contributing to the problem.[145]

—Chief Justice Tani Cantil-Sakauye, California Supreme Court, March 12, 2016

The DA’s objective in making the bail so high and then raising it again when we came up with the original amount was solely to force a plea bargain. Then they kept dragging it out. They were not in it for justice, they were in it for statistics.[146]

—Kevin Ocampo, Alameda County resident, who posted bond for his cousin, May 27, 2016

It’s like someone walks up and puts a gun to your head and says, “Hey, give me your money.”[147]

—Oscar De La Torre, executive director of Pico Youth and Family Center, November 21, 2016

Bail Coerces People into Giving Up the Right to Trial

According to the latest available data:

- 80.8 percent of California filed felony cases resolve through guilty pleas;

- 16.7 percent are dismissed or transferred to another jurisdiction;[148]

- 2.5 percent go to trial.

For non-traffic misdemeanors:

- 62.3 percent result in guilty pleas;

- 35.8 percent are dismissed or diverted;

- Just under 1 percent go to trial.

In felony cases, of those that go to trial:

- 81 percent result in some felony guilty verdict;

- 3 percent result in a reduced misdemeanor verdict;

- 14 percent result in acquittal or dismissal.[149]

Though impossible to quantify, a large number of the guilty pleas represented in the above statistics happen because defendants are detained pretrial and see pleading guilty as their quickest way out of jail.[150] Pretrial prisoners know they will have to wait approximately 30 days on a misdemeanor case and 90 days on a felony case before they go to trial.[151] Prosecutors and judges often offer settlement terms that result in the defendant getting out sooner than it would take to get to trial.[152] Defendants feel this coercion acutely and often give up their right to trial in order to be released.

Studies in different jurisdictions nationwide have found a correlation between pretrial detention and likelihood of conviction, as well as likelihood of a custody sentence and the length of that sentence.[153]

Researchers have attempted to determine whether or not pretrial detention actually causes those negative consequences, by controlling for factors like severity of crime and criminal history that would otherwise affect the results. One study looked at all cases in Philadelphia’s criminal courts and found being in pretrial detention increased likelihood of conviction by 13 percent, primarily through an increase in guilty pleas.[154] On average, those detained received jail or prison sentences five months greater than those fighting their cases from outside. They paid significantly more in court fees. The effect was 17 percent larger for first and second time offenders.[155]

Another significant finding of the Philadelphia study was the distinction drawn between “strong evidence” cases and “weak evidence” cases. “Strong evidence” cases were those like drug or gun possession, in which police most likely found the person with the contraband, or driving under the influence cases, in which a blood-alcohol test objectively measures intoxication. These are cases in which guilt is not easily disputed, so high rates of guilty pleas are expected.

“Weak evidence” cases like assault or burglary or robbery, in which there is often an eyewitness identification question or a self-defense issue, are more readily contested. All else equal, “weak evidence” cases should be more likely to go to trial, as they are harder to prove, and easier to defend. The study found the impact of pretrial detention on guilty pleas much more pronounced for “weak evidence” cases, indicating that pretrial detention was pressuring people who should be expected to fight their cases to plead guilty.[156] The Philadelphia study found similar results for black as for white defendants.[157] However, in a jurisdiction that incarcerates a vastly greater proportion of black people, the negative consequence has racial impact. Other studies in Texas, Philadelphia, New York, and Miami have reached similar conclusions.[158]

The criminal system in California may not follow the exact patterns of the jurisdictions studied by the researchers cited above. However, the findings from these jurisdictions are consistent, the framework of their court systems and pretrial detention decision-making processes are not significantly different from those in California, and no study in any California county has revealed contrary findings.