Imagine that your parents fled their country with you 30 years ago, when you were a baby. The country where you live is the only place you have ever known and your own children were born there.

But you wake up one day and hear a government media campaign saying it is time for you and 2.5 million others like you to pack your bags and return home. You are told your residence permit will expire in a few months, in the middle of a bitterly cold winter. If you leave now, you and your family will receive a generous cash grant from the United Nations. But if you wait you could face being deported with nothing.

Soon afterward, the police barge into your home at night, ransack your belongings and ask why you are still there. Then police stop you every day in the street and take your daily wages. Your children are kicked out of school, your landlord triples the rent and previously friendly neighbors tell you to leave. And the U.N. agency that is supposed to protect your rights stays publicly silent about the crackdown.

What would you do?

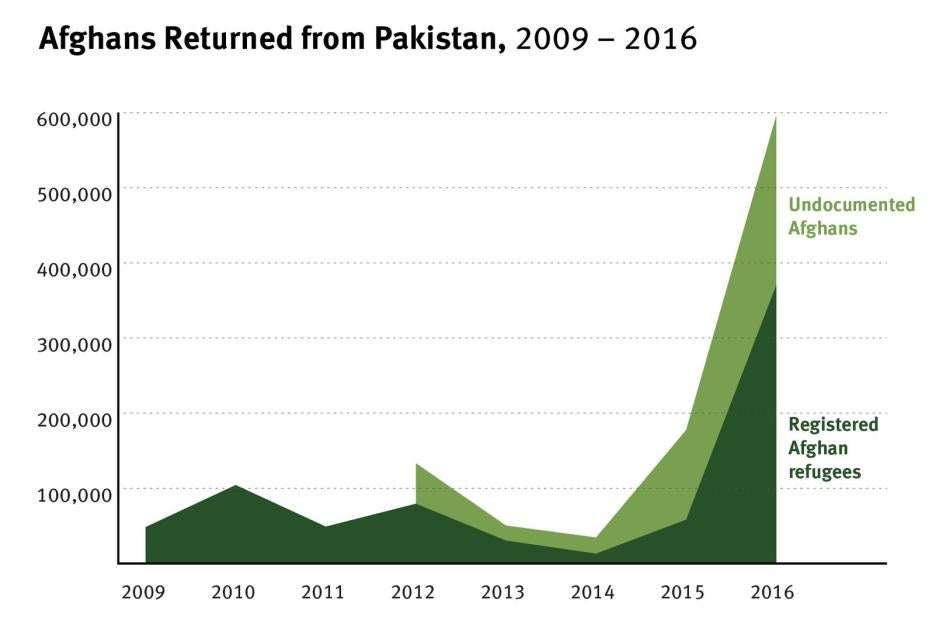

In the second half of last year, 600,000 Afghans in Pakistan, including 365,000 registered refugees, faced a barrage of police abuses and deportation threats and answered that awful question by hurriedly piling their worldly possessions onto trucks and crossing the border. It was a return to nothing in Afghanistan: no homes, no land and no jobs, schools or clinics. Many joined the ranks of Afghanistan’s 1.5 million displaced, driven out of their villages by the country’s spiraling conflict. The exodus amounts to the world’s largest unlawful forced return of refugees in recent years.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) has a long history in Pakistan. Between 2002 and the end of 2014, it helped about 3.7million Afghans return voluntarily to their country. During the first half of 2015, when many of the 60,000 registered refugees who returned to Afghanistan clearly did so under pressure, the UNHCR made no public call for an end to the abuses.

The UNHCR is a pragmatic agency that often muddles its way through a crisis to avoid offending the countries that host it in order to assist and protect refugees. And there is no doubt that the U.N.’s refugee agency is operating in a tough political environment in Pakistan. But in failing to take a principled and public stand against Pakistan’s clampdown, it has crossed a clear red line that has put the agency on the wrong side of refugee protection history.

The UNHCR maintained its public silence as the abuses and resulting departures accelerated in 2016. The agency instead euphemistically said the Afghan refugees were returning “under difficult circumstances” to describe what clearly amounted to an unlawful coerced return. Rather than try to stop returns, the agency facilitated them under significant pressure from Pakistan, doubling its cash grant to $400 for every returning Afghan refugee.

This was an astronomical amount of money for the average Afghan family. Many returnees whom I met in Kabul said they had been uncertain what to do but were afraid that, if they did not take the money, they would end up being deported anyway, penniless.

The UNHCR’s public silence on the abuses and threats, together with the cash incentive and its failure to provide refugees with timely, full and accurate information about security and conditions inside Afghanistan, meant that it was effectively promoting involuntary refugee return. This is not only contrary to its mandate but made the agency complicit in forced refugee returns.

The UNHCR maintains it did no such thing, but actions – and inactions – speak louder than words. And in this case the agency’s silence so embarrassed junior UNHCR staff members in Afghanistan last year that they broke with the official line and told journalists that the returns were “forced” and “not voluntary.”

Pakistan has made clear it wants to see hundreds of thousands of more returns in 2017 and is now threatening to deport the remaining 2.5 million Afghans in the country next January if they don’t leave before then.

The UNHCR has responded to this renewed threat by planning to resume its cash support in March, though at a reduced rate. In the absence of a commitment from authorities in Pakistan to end all police abuses and stop threatening mass deportations, Afghan refugees will continue to leave Pakistan involuntarily, under pressure. The UNHCR should not play a part in these violations of international law. If it believes giving refugees cash is the best way to help them survive destitution and insecurity back home, it should first recognize publicly that the returns are not voluntary.