Summary

“No matter who you are, your heart will turn black with so much abuse.”

-Afghan refugee, 25, returning to Afghanistan, November 2016

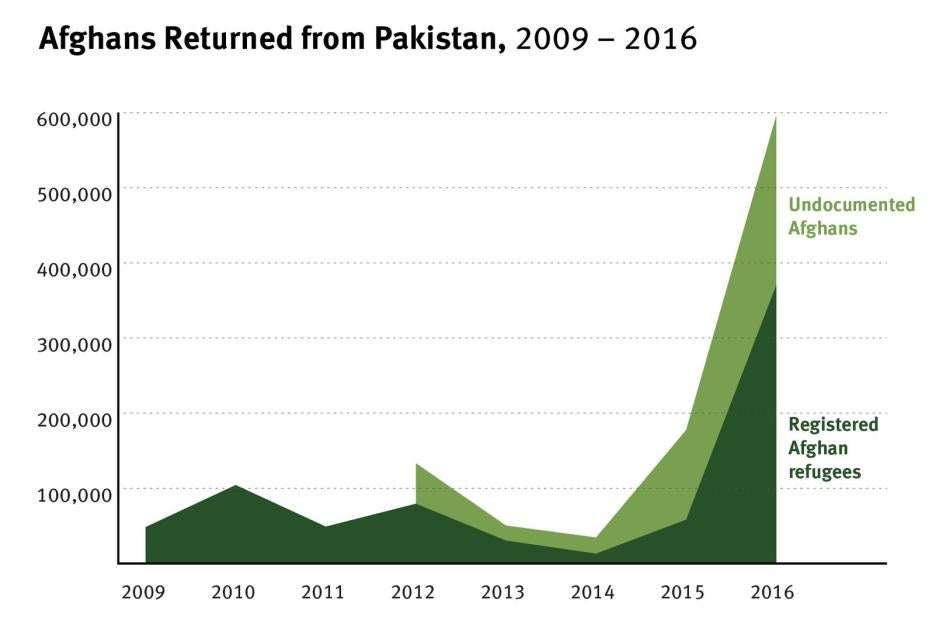

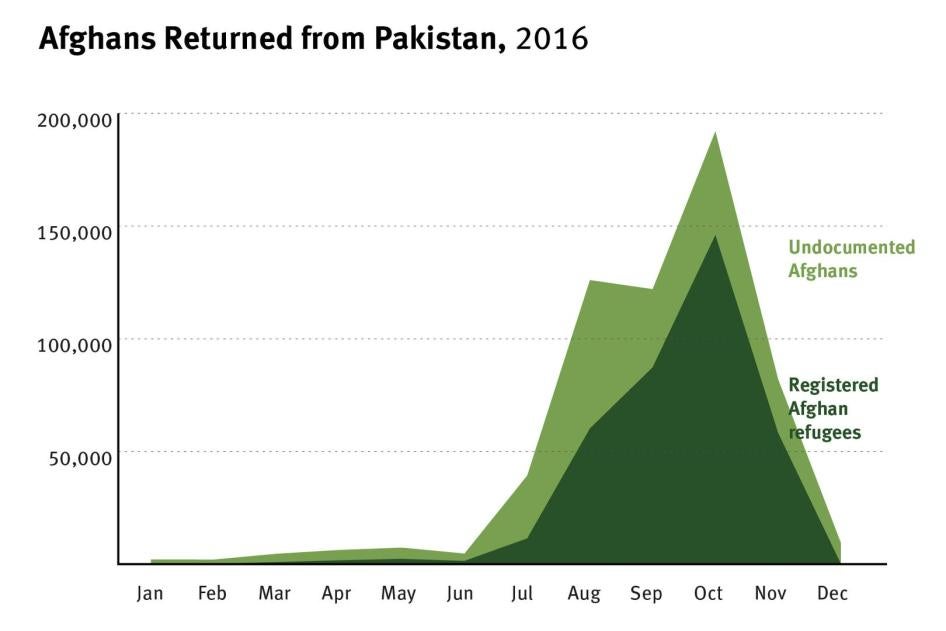

For most of the past 40 years, Pakistan has hosted well over a million Afghans, among the largest refugee populations in the world. But over the past two years, Pakistan has turned on the Afghan community. In response to several deadly security incidents and deteriorating political relations between Pakistan and Afghanistan, Pakistani authorities have mounted a concerted campaign to drive Afghans out of the country. In the second half of 2016, a toxic combination of deportation threats and police abuses pushed out nearly 365,000 of the country’s 1.5 million registered Afghan refugees, as well as just over 200,000 of the country’s estimated 1 million undocumented Afghans. The exodus amounts to the world’s largest unlawful mass forced return of refugees in recent times. Pakistani authorities have made clear in public statements they want to see similar numbers return to Afghanistan in 2017.

Driven from relatively stable security and economic conditions in Pakistan, the Afghans pushed out are returning to expanding armed conflict in Afghanistan. They also face widespread destitution and a near-total absence of social services, a situation the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the UN refugee agency, has described as a “humanitarian emergency” that aid agencies are “severely constrained in addressing … due to increasing insecurity and … dwindling resources.” Unable to return to insecure and poverty-stricken home areas, hundreds of thousands risk joining the 1.5 million Afghans estimated at the end of 2016 to be “internally displaced” within their own country, including almost 625,000 displaced in 2016 alone. This figure excludes the hundreds of thousands of returnees from Pakistan who were unable to return home in 2016. In December 2016, UNHCR warned that the massive number of returns from Pakistan could “develop into a major humanitarian crisis.”

This report—based on 115 interviews with refugee returnees in Afghanistan and Afghan refugees and undocumented Afghans in Pakistan, and further corroborated by UN reports that present the reasons thousands of Afghans gave for coming home—documents how Pakistan’s pressure on Afghan refugees left many of them with no choice but to leave Pakistan in 2016.

Afghans described to Human Rights Watch various coercive factors that began in June 2016 after relations between Afghanistan and Pakistan deteriorated, including: increasingly insecure legal status; government announcements that all Afghans should leave, and the resulting ever-present threat of deportation; daily police extortion that intimidated and stripped them of their limited income and ability to make ends meet in Pakistan; arbitrary detention; police raids on their homes; exclusion of their children from Pakistani schools and shutting down Afghan refugee schools; and, to a lesser extent, police theft and unlawful use of force. Pakistani police abuses decreased in October 2016, although reports of ongoing abuses continued well into December.

Key among these factors was Afghan refugees’ insecure legal status and the related threat of deportation. Until mid-September 2016, Pakistan said the refugee status of Afghan refugees would expire on December 31, after which Afghan refugees were told they would be required to leave or be deported, and in September the authorities extended that date until March 31, 2017. On November 23, the Pakistani federal cabinet reportedly approved an extension of Afghan refugees’ status until the end of 2017. However, as of late January, any such decision had not been made public, leaving Afghans in fear of deportation in early April.

Before 2016, Pakistan renewed Afghans’ refugee status for between 18 months and three years at a time. By extending refugee status for only 12 months or less after that time, and by refusing to re-issue refugees’ expired cards after December 2015, Pakistani authorities increased the pressure to return.

Returning refugees also spoke about other factors that influenced their decision to leave. For many, the June 2016 decision of UNHCR—under significant pressure from Pakistan seeking increased repatriation rates—to double its cash grant to returnees from US$200 to US$400 per person was a critical factor in persuading them to escape Pakistan’s abuses. Many described other factors adding to the misery of official abuses, including a sudden emergence of anti-Afghan hostility by local Pakistani communities, Pakistani landlords suddenly charging significantly increased rent for apartments and business premises, and the departure of most or all of their relatives and neighbors, which left them feeling exposed and vulnerable to local police abuses.

Pakistan is bound by the universally binding customary law rule of refoulement to not return anyone to a place where they would face a real risk of persecution, torture or other ill-treatment, or a threat to life. This includes an obligation not to pressure individuals, including registered refugees, into returning to places where they face a serious risk of such harm.

Pakistan’s coercion of hundreds of thousands of registered Afghan refugees into returning to Afghanistan violates the international legal prohibition against refoulement.

Since early 2007, Pakistan has not registered any new Afghan refugees, despite the lack of meaningful improvement in human rights conditions in Afghanistan since then. As UNHCR in Pakistan does not have the capacity to register and process the claims of tens or hundreds of thousands of asylum seekers, only a limited number of Afghans have been able to seek protection with UNHCR, leaving the rest without secure legal status.

Unknown numbers of undocumented Afghans who left Afghanistan for the same sorts of reasons as those who were registered as refugees before 2007, and who have wanted—but not been allowed—to file asylum claims with the Pakistani authorities should therefore also have a protected status in Pakistan, but have been denied it. Many of the 205,000 undocumented Afghans coerced out by Pakistan’s abuses since July 2016 may therefore also be victims of refoulement.

Human Rights Watch calls on Pakistan to avoid recreating in 2017 the conditions that coerced Afghan refugees to leave in 2016. This means Pakistan should act to end all police abuses and revert to its previous policy of extending Proof of Registration (PoR) cards by at least two years. To avoid creating anxiety about possible deportation in the middle of winter, it should extend cards until at least March 31, 2019 and commit to announcing by latest October 31, 2018 whether the authorities plan to extend the cards by a further two years beyond that date. The authorities should also allow undocumented Afghans seeking protection to request and obtain it in Pakistan.

In the second half of 2016—when hundreds of thousands of Afghan refugees and undocumented Afghans were unlawfully coerced out of Pakistan—UNHCR remained publicly silent about Pakistan’s large-scale refoulement of Afghans, not once stating that many of those returning were primarily fleeing police abuses and fear of deportation and that Pakistan’s actions were unlawful.

Instead, the agency referred in low-visibility updates for international aid donors to a range of factors that were contributing towards Afghan refugees’ decision to leave Pakistan and repeatedly referred to “facilitating voluntary repatriation.” UNHCR said it raised concerns with the Pakistani authorities behind-the-scenes on individual abuse cases or localized abuses, but this approach was a woefully inadequate response to the widespread abuses that were affecting hundreds of thousands of Afghans and that continued unabated for at least three months.

Under its mandate, UNHCR may “facilitate” voluntary refugee repatriation, even where UNHCR does not consider that it is safe for most refugees to return or that their return amounts to a “durable solution.” UNHCR may only “promote” large-scale refugee repatriation when, among other things, UNHCR has formally concluded there is an overall general improvement in the refugees’ country of origin so that they can return in “safety and dignity” and rebuild their lives there in a “durable” manner. Absent reintegration into the local community, voluntary repatriation is not a durable solution. In both cases—facilitation or promotion—UNHCR must be convinced that refugees are in fact returning voluntarily before it supports their repatriation.

By doubling its cash support to each returning refugee to $400 in June 2016 and maintaining this support until mid-December 2016 while referring publicly to its “voluntary repatriation” work, UNHCR effectively promoted the repatriation of Afghan refugees.

But as this report shows, conditions in Afghanistan have not significantly improved, so vast numbers of returnees have been unable to return to their home areas due to insecurity and extreme poverty. UNHCR failed to ensure that refugees were fully informed of the conditions to which they were returning before deciding to leave. And regardless of conditions in Afghanistan, huge numbers of refugees leaving Pakistan in the second half of 2016 did not return voluntarily. UNHCR therefore fundamentally abrogated its refugee protection mandate by effectively supporting Pakistan’s mass refoulement, thereby making UNHCR complicit in these violations.

On January 27, UNHCR wrote to Human Rights Watch, saying “UNHCR shares your concerns regarding the reported push factors affecting the repatriation from Pakistan,” that “UNHCR strongly refutes the claim that increasing the cash grant constituted promotion of return,” and that the agency “provide[d] support to refugees who make the decision to [return] based on a well-informed consideration of best options” which helped them “meet their most immediate humanitarian needs.” UNHCR added that it had nonetheless decided to “reassess whether the cash grant had become a pull factor.”

Coinciding with the onset of winter weather, in early November, UNHCR announced it would suspend cash support to returnees in December, saying it had run out of money. As of late January 2017, UNHCR was planning to resume cash support to returnees in early March if donors commit sufficient funds. If UNHCR does so, but remains publicly silent on any further coerced return resulting from Pakistan’s threat to deport Afghan refugees at the beginning of April 2017 and possibly from continued police abuses, the agency will continue to be complicit in refoulement.

As long as Pakistan’s campaign of coerced repatriation continues, UNHCR should publicly state Pakistan is in breach of its commitments under the Tripartite Agreement with Afghanistan and UNHCR on the repatriation of Afghans in order to ensure they are returning voluntarily. By failing to publicly state Pakistan has breached its commitments, UNHCR also failed to perform its own supervisory role under the agreement, which requires it to ensure that Afghan refugees’ repatriation is voluntary.

UNHCR should also suspend its participation in the Tripartite Agreement. Although the agreement commits the parties to ensuring the voluntariness of refugee return, Pakistan flouted those standards in 2016. Continuing to participate in the agreement implies that UNHCR views the current forced returns from Pakistan as voluntary. UNHCR should only resume its participation in the agreement when Pakistan ends its coercion of Afghan refugees and provide them a real choice about whether to stay or leave.

UNHCR should also publicly speak out against any renewed refoulement and make clear that any support it might give to returning Afghan refugees in 2017, whether cash or other forms of support, is driven by the humanitarian aim to minimize suffering resulting from sudden forced return and is not to be viewed as support for the Pakistani position that they returned “voluntarily.”

Faced with almost 350,000 Afghan asylum seekers between January 2015 and September 2016, European Union member states have increasingly rejected Afghan asylum claims. In October 2016, the EU used development aid to pressure Afghanistan into accepting increased deportations of rejected Afghan asylum seekers to a country the EU said in late 2016 was facing “an increasingly acute humanitarian crisis.”

European Member States should exercise discretion to defer deporting rejected Afghan asylum seekers until it becomes clear how Kabul—where the UN estimates roughly 25 percent of refugee returnees from Pakistan in 2016 have settled—will cope with the massive influx. Otherwise the EU will risk fueling the very instability the EU says it wants stopped.

Human Rights watch calls on international donors to help the Pakistani authorities properly assist and protect Afghan refugees until it is safe for them to return home. It calls on UNHCR to speak out as necessary and challenge any repeat in 2017 of the appalling and unlawful pressure Pakistan placed on Afghans in 2016 that coerced many to return to danger and destitution in Afghanistan in such massive numbers. And it calls on the Humanitarian Country Teams in Pakistan and Afghanistan to speak out if UNHCR fails to do so.

Key Recommendations

To the Pakistani Government

- Publicly assure all registered Afghan refugees that they will be allowed to stay in dignity in Pakistan until it is genuinely safe for them to return to Afghanistan.

- To end mass refoulement of Afghan refugees, stop setting short-term deadlines for the expiration of refugees’ Proof of Registration cards and stop making related deportation threats; instead revert to the previous two-year extension policy and extend cards until at least March 31, 2019, while committing to extend them at the latest by the end of October 2018; continue to extend cards’ validity until Afghanistan has reached a point of stability to enable safe and dignified return in line with international standards.

- To avoid refoulement of refugees among undocumented Afghans in Pakistan, re-open registration for Proof of Registration cards so that Afghans who arrived after mid-February 2007 can obtain such status, or provide a comparable blanket protection against forced return.

- Issue a written directive instructing all relevant government officials and state security forces to end their abuses against registered and undocumented Afghans, including extortion, arbitrary detention, house raids without warrants, unlawful use of force, and theft; investigate and appropriately prosecute police and other officials responsible for serious abuses against Afghans.

To the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)

- Reverse UNHCR’s 2016 practice of remaining silent in the face of mass refoulement by Pakistan, and monitor and publicly condemn any renewed coercion against Afghan refugees resulting in refoulement.

- Publicly state that Pakistan is in breach of the 2003 Tripartite Agreement on the Voluntary Repatriation of Afghans unless it ends the coerced return of Afghan refugees and suspend UNHCR participation in the agreement until such coercion ends.

- Press Pakistan to extend Proof of Registration cards until at least March 31, 2019, end police abuses against Afghans, and otherwise protect those needing continued protection from forced return.

- If UNHCR resumes cash support to returning Afghan refugees in 2017 without Pakistan meeting those requirements, publicly state—to avoid further complicity in mass refoulement—that such support does not amount to an endorsement of Pakistan’s claims that forced returns are in fact voluntary.

To the Humanitarian Country Teams in Afghanistan and Pakistan

- If UNHCR maintains its public silence over any renewed mass refoulement of Afghan refugees from Pakistan, publicly call on the Pakistani authorities to stop coercing Afghan refugees back to Afghanistan.

To Donor Governments, including European Union Member States, Providing Support to Pakistan

- extend Afghan refugees’ Proof of Registration cards until the end of March 2019 and to re-open registration for the cards or other protected status so that Afghans who arrived after February 2007 can seek and obtain protected status in Pakistan; also press them to end police abuses against all Afghans.

- Press UNHCR to publicly state Pakistan is in breach of the Tripartite Agreement until Pakistan ends police abuses against Afghan refugees and stops otherwise coercing their return and press UNHCR to suspend its participation in the agreement until such coercion ends.

- Press UNHCR to speak out publicly against any renewed refoulement of Afghans.

To European Union Member States

- Exercise discretion to defer deporting rejected Afghan asylum seekers, until it is clear how Kabul and other parts of the country cope with Pakistan’s mass forced return of Afghan refugees.

Methodology

Between October 26 and November 1, 2016, Human Rights Watch interviewed 92 Afghan refugees who had returned to Kabul about why they had left Pakistan. Between November 8 and 11, 2016, Human Rights Watch also interviewed 23 Afghan refugees and undocumented Afghans in Peshawar, Pakistan, about problems they faced in Pakistan. All but three of the interviewees were men.

In Kabul, two Human Rights Watch researchers, including a fluent Dari and Pashtu speaker, and an Afghan interpreter conducted the interviews at UNHCR’s encashment center in Kabul. In Peshawar, a Human Rights Watch researcher fluent in Urdu and an interpreter fluent in Pashtu spoke with Afghans living there. All interviews were conducted individually in private. Researchers explained the purpose of the interviews and gave assurances of anonymity. We also received interviewees’ consent to describe their experiences. No interview subject was paid or promised or provided a service or personal benefit in return for their interviews.

Human Rights Watch also met with the Afghan Minister of Refugees and Repatriations, Sayed Hussain Alemi Balkhi, and with seven international non-governmental organizations and five UN agencies in Kabul about the fate of returning refugees in Afghanistan. Human Rights Watch met on a number of occasions with UNHCR in Geneva and in Kabul and spoke by telephone with UNHCR staff based in Islamabad. Human Rights Watch sent a draft copy of this report to UNHCR on December 23, 2016 and received written feedback on January 27.

On January 12, 2017, Human Rights Watch wrote to Pakistan’s Minister of States and Frontier Regions outlining our findings and requesting comment. At the time of writing, Human Rights Watch had not received a response.

I. Background

Pakistan’s Refugee-Hosting History

Pakistan has been one of the world’s longest-serving refugee-hosting countries in recent decades. Since 1978—when large numbers of Afghans first started fleeing violence in their country following the communist coup and subsequent Soviet invasion—Pakistan has never sheltered fewer than one million Afghans and, between 1986 and 1991, it hosted about three million.[1] Waves of conflict and periodic widespread droughts and economic collapses amidst some relatively more stable periods have seen large numbers of Afghans continue to flee, return home, and then flee once again.[2] Between 2002 and late 2015, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) helped 3.9 million Afghans return home.[3] Of those, almost 2 million returned by the end of 2008 when the rate of return significantly decreased.[4] In response, in 2012, the Afghan, Pakistani, and Iranian governments and UNHCR sought to kick-start the returns process through a “Solutions Strategy,” with very little success.[5]

By the end of 2015, there were 1,560,592 registered Afghan refugees in Pakistan, together with another one million unregistered Afghans the Pakistani authorities estimated were also in the country.[6] The mass exodus of just under 600,000 Afghans from Pakistan in 2016, including 370,000 registered refugees and 230,000 undocumented Afghans, means that the total figure of about 2.5 million Afghans had dropped to about 1.9 million by the end the year.[7] As of late 2015, 62 percent of registered Afghans lived in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province while a further 20 percent lived in Balochistan province, both bordering Afghanistan.[8]

By the end of 2016, Iran was also hosting almost 1 million registered Afghan refugees.[9] As of May 2016, the authorities estimated up to 2 million undocumented Afghans were in the country.[10] As of September 2016, Turkey hosted about 120,000 registered Afghan asylum seekers.[11] The European Union hosted the majority of the rest of the world’s Afghan registered refugees and asylum seekers, with about 350,000 lodging claims between January 2015 and September 2016.[12] At the end of 2015, registered Afghan refugees and asylum seekers made up 12.5 percent of the global refugee population.[13]

Pakistani Police Abuses in 2015

Prior to late 2014, Afghan nationals in Pakistan—whether registered as refugees or undocumented—lived in relative peace, despite a period of concerted abuse of Afghans by the Pakistani authorities between 2000 and 2002.[14] The authorities allowed them to work in the informal sector, although Afghan children lucky enough to access schools have depended on the United Nations.[15] Many Afghans established close connections with local communities.[16]

However, a month after the December 2014 attack by the so-called Pakistani Taliban, Tehreek-i-Taliban Pakistan, on Peshawar’s Army Public School, which killed 145 people, including 132 children, the Pakistani authorities adopted a National Action Plan on Counter-Terrorism. This included a new policy to register and repatriate Afghans from Pakistan, despite the fact that the Pakistani government’s own investigations did not find any “significant Afghan involvement in acts of terrorism,” while the Minister for States and Frontier Regions (SAFRON) stated there was no evidence that registered Afghan refugees had ever been involved in “terrorism-related” activities in Pakistan.[17]

UNHCR concluded that the counter-terrorism plan had “multiple implications for the treatment and protection of … Afghan refugees whose presence in Pakistan is often associated with the prevailing security situation.”[18] Human Rights Watch documented the consequences of the plan, which included a wave of Pakistani police abuses against Afghans, such as unlawful use of force, arbitrary arrest and detention, extortion and house demolitions.[19]

These abuses decreased after July 2015, but UNHCR confirmed that police harassment and intimidation, and Afghans’ fear of arrest and deportation, continued to drive Afghans out of Pakistan as late as September 2015.[20] Most Afghans Human Rights Watch interviewed for this report said that police abuses significantly decreased during the last few months of 2015. By the end of the year, 58,211 registered Afghan refugees had returned to Afghanistan, up from 12,991 in 2014.[21]

II. Pakistan’s Mass Refoulement of Afghan Refugees

In the last six months of 2016, a campaign of police abuses and government announcements that it was time for all Afghans to leave Pakistan, combined with their insecure legal status, drove just under 365,00 registered Afghan refugees and just over 200,000 undocumented Afghans out of Pakistan, including unknown numbers among them seeking protection.[22] This coerced exodus amounts to the largest unlawful mass forced return of refugees and asylum seekers in the world in recent times.[23]

International Law Prohibiting Forced Return to Harm

Pakistan is bound by customary international law’s prohibition on refoulement not to forcibly return anyone to a place where they would face a real risk of persecution, torture or other ill-treatment, or a threat to life.[24] Pakistan is also bound by the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment not to return anyone to states where they would be in danger of such treatment.[25]

The principle of nonrefoulement prohibits forcing a person back to face these dangers in “any manner whatsoever.”[26] This includes situations in which governments put so much direct or indirect pressure on individuals that they have little or no option but to return to a country where they face serious risk of harm.[27] For example, UNHCR contends that denying asylum seekers income support or other income-related benefits may force asylum seekers “into unlawful exploitative conditions to support themselves …[that] could bring them into conflict with the law” and that when “confronted with these choices even genuine but desperate refugees might be compelled to return to face persecution in the country of origin, rather than remain in an impossible position” in the country of asylum “which could amount to ‘constructive refoulement’ [that] may place the [country of asylum] in violation of its obligations under the Refugee Convention."[28]

UNHCR’s Handbook on Voluntary Repatriation also says that if refugees’ “rights are not recognized, if they are subjected to pressures and restrictions … they may choose to return, but this is not an act of free will.”[29]

Coercive Factors Driving Out Afghan Refugees

Afghans interviewed for this report said the reduction in police abuses in late 2015 continued during the first half of 2016. However, three key developments then appeared to trigger a renewed and intensified round of abuses, coupled with government statements that all Afghans should leave Pakistan.

In May 2016, Afghanistan, India and Iran signed trade deals which will use Afghanistan as a transit route for Indian goods destined for Central Asia and Russia, thereby bypassing Pakistan entirely.[30] Given its long-standing enmity towards India, Pakistan viewed the deal as further evidence of India’s growing influence in Afghanistan and the broader region.[31] Returning refugees told Human Rights Watch and UNHCR that Pakistani communities who had peacefully hosted them for decades suddenly started calling them “sons of Hindus,” apparently referring to Afghanistan’s closer ties to India and the perceived resulting threat to Pakistan.[32]

On June 3, Afghan President Ashraf Ghani and Indian Prime Minster Narendra Modi inaugurated the Salma Dam, a hydro-electric power station in Afghanistan’s Herat Province and a powerful symbol of the two countries’ bilateral ties.[33]

Then, on June 12, Afghan and Pakistani forces clashed at the Torkham border crossing, killing an Afghan soldier and a Pakistani major and sparking anti-Afghan protests in Pakistan.[34]

Returning Afghan refugees and Afghans in Peshawar described to Human Rights Watch in October and November how police abuses began again in earnest in late June 2016, and were accompanied by constant government threats in the media to deport all Afghans by the end of the year. Interviewees said this combination drove them out of Pakistan or, in the case of those still living in Peshawar, put them under so much pressure that they were planning to return to Afghanistan.

Returning Afghan refugees said the abuses and threats that drove them out included: widespread police extortion, arbitrary detention, deportation threats from Pakistani government officials, police raids on refugee shelters and apartments, exclusion of Afghan children from state schools and closure of Afghan refugee schools, and police unlawful use of force and theft.

Police Extortion, Arbitrary Detention and Destruction of Refugee Cards

Almost every Afghan interviewed for this report described how beginning in July 2016, Pakistani police repeatedly stopped and extorted from them between 100 and 3,000 rupees [US$1 - US$30] each time. In many cases the police used the fact that refugees’ Proof of Registration (PoR) cards had expired at the end of December 2015 as an excuse to demand money and threatened to confiscate their cards or deport them if they didn’t pay.[35]

A 22-year-old Afghan man living in Mansehra district, Khyber Pakhutkhwa province, said:

They stopped me about 15 times in August and September and each time they took away my refugee card and said I had to pay to get it back. Sometimes they said, “We need to get all your money before you leave the country.”[36]

Many refugees said the police took all their earnings so that it made no sense to go to work. A 28-year-old man living in Board Tajabad town near Peshawar said:

The situation with the police got so bad about three weeks ago [early October 2016] that we could not leave the house. The police were stopping us all the time, asking for money. They took everything we had so we stopped working and just stayed at home. We realized we had to leave [Pakistan].[37]

Dozens of Afghans described how police arbitrarily detained them or relatives, including sick, elderly people, in police stations for between a few days and two months, and extorted up to 50,000 rupees ($US500) per person in exchange for their release. Several interviewees said that the police first gave them a choice to pay in the street and said if they didn’t, they would take them to police stations where they would demand far greater sums of money.

A 52-year-old man living in the Hayatabad neighborhood of Peshawar city said:

Police were constantly taking us to police stations because our refugee cards had expired. Many times they took me there and said that if I did not pay them, they would tear up my card. The last time was about two months ago [late August] and I had to pay 10,000 rupees [$US100] to get out. Each time I asked, “Why are you doing this?” and they replied, “Because you are a refugee.”[38]

Many returnees at UNHCR’s encashment center in Kabul said that in the past local residents would help Afghans get released from police custody by paying the police, but that after June that support stopped.[39]

Five returning refugees told Human Rights Watch that police officers in the streets and police stations tore up their refugee cards, which left them feeling even more insecure than before.[40]

Increasingly Insecure Legal Status and Deportation Threats

Almost all returning Afghan refugees said a key factor in their decision to return was their increasingly insecure legal status in Pakistan, which led to a constant fear of deportation.

Based on Pakistan’s first and only country-wide census of Afghans in 2005, Pakistan in early 2007 gave 2.15 million individuals official legal status as an “Afghan citizen temporarily residing in Pakistan.”[41] Each person was given a “Proof of Registration” card, valid until the end of 2009.[42] UNHCR considered this registration to be equivalent to refugee status and the Pakistani authorities refer to card-holders as “refugees.”[43]

The cards were extended for a further three years until the end of 2012.[44] After a six-month period of uncertainty during which time the police were instructed to treat the expired 2012 cards as valid, in July 2013 the cards were extended until the end of 2015.[45] The authorities then extended them twice for six months, until the end of 2016.[46] However, the authorities didn’t issue new cards in 2016. Afghan refugees told Human Rights Watch that when they attempted to obtain new cards, local officials told them to show police their expired 2015 card.[47] Some also showed Human Rights Watch “tokens”—laminated cards with text apparently from local newspapers which referred to the June and December 2016 extensions—which they had bought in shops.[48]

Ten days before the UN General Assembly met in New York on September 19, 2016 to discuss the global refugee crisis, Pakistan extended the cards’ validity by a further three months until the end of March 2017, but again did not issue new cards.[49] A senior UN official told Human Rights Watch the extension was made to avoid criticism at the UN from other governments concerned about Pakistan’s increasingly aggressive stance towards Afghan refugees.[50] According to UNHCR, on November 23, 2016—by which time almost 650,000 Afghans had returned home—the Pakistani federal cabinet approved the extension of the Proof of Registration card until December 31, 2017, but as of late January, has made no public announcement to that effect.[51] In early January, UNHCR said Afghan refugees had left Pakistan due, in part, to the “lack of clarity regarding the extension of proof of registration … cards beyond March 2017.”[52]

Afghans told Human Rights Watch that the steady reduction in the security of their legal status—resulting from the shorter refugee card extension periods since late 2015—and police frequently saying their expired 2015 cards were invalid, despite government announcements extending their validity, had left them feeling exposed to the risk of deportation. Most said that the fact that police repeatedly accused them of illegal presence in Pakistan proved the authorities were determined to drive out all Afghans.

UNHCR has acknowledged that “the temporary validity of PoR [Proof of Registration] cards … has been repeatedly interpreted as a deadline for the stay of Afghan refugees … and, coupled with extension delays, has created pressures for Afghans to return.”[53] UNHCR has also said that the “short-term extensions of the validity of PoR cards” has resulted “in heightened anxiety and lack of predictability.”[54] And on leaving her position in Kabul in January 2017, UNHCR’s representative in Afghanistan said that “time frames such as validity of Proof of Registration cards for refugees in Pakistan, which have become increasingly shorter since the end of 2015, cannot be regarded as “deadlines” for return – these are incompatible with voluntariness of repatriation.”[55]

Many Afghans described how starting in June 2016, the Pakistani authorities began to use the media and other forums to tell Afghans they should leave the country.

A 32-year-old man living in the Afghan Kaluni neighborhood of Peshawar city said:

When the cards expired at the end of 2015 the authorities said that they were ok for another six months and then they said until the end of the year. But about one month after Torkham [the border clashes in June 2016] they said many times on television we should leave straight away. Then they drove around in cars with loudspeakers in my neighborhood with the same message, two or three times a day. Then we saw the message in newspapers and the local mosques said the same.[56]

Others described how they feared imminent arrest and deportation and didn’t trust government announcements saying their expired Proof of Registration cards from 2015 were still valid until the end of the year or the end of March 2017. As one man said, “We didn’t know whether we would be allowed to stay, but knew they would come for us quickly when our time was up.”[57]

Others said they feared they would be deported overnight, without time to sell their possessions, so they preferred to leave as a precaution before they lost everything.[58]

Several returning refugees said they were afraid that they would be deported overnight and split from their families and therefore decided to leave to avoid the worst.[59] As a man living in the Jalala camp in Mardan district in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) province said, “I was afraid that the police might just take me and leave my wife and children behind and that I wouldn’t be able to help them get out of Pakistan.”[60]

Finally, many returnees said that the threat of deportation during the winter was too great a risk to take and that they preferred to leave between August and October to do whatever they could to find shelter for themselves and their families before the weather turned cold.[61]

Police Raids

Dozens of interviewees said that, mostly in July and August, various security forces raided the settlements or neighborhoods where they lived and entered Afghans’ homes by day or night without asking permission, including when all the men were at local mosques and women were alone at home. Many said women and girls felt particularly threatened by these raids and that it violated their families’ honor and dignity. Most said that soldiers or police officers conducting the raids told them that all Afghans were on the brink of being deported, and took some relatives to police stations to extort money. Some said officers in their homes accused them of being terrorists.[62]

UNHCR confirmed that many returnees in Kabul spoke of a new trend of nocturnal police raids in Pakistan that left them fearing for the safety of female relatives and violated their privacy and dignity.[63]

A 27-year-old man living in “Camp Number 4” in the Jani Khor tribal area in the Badaber district of KP Province said:

In early August, when it was very hot, the police came to our house very early in the morning, about 4:30 a.m. They entered our house without asking, pushed all the women to one side and took all of the men, including me, to the police station. The women were all very afraid. There were about 200 other Afghans at the station when we arrived. They held us there all day and did not give us water or let us go to the toilet. Our relatives came and paid to get us out. In early October, I saw in a newspaper that the police would do more search operations and that they were going to put Afghans in prison. So we knew we had to leave.[64]

Closure of Afghan Refugee Schools and Exclusion of Afghan Refugee Children from Pakistani Schools

About half of the Afghans Human Rights Watch interviewed said that beginning in May 2016, their children had been excluded from Pakistani state schools or that the authorities had shut down Afghan refugee schools. Many cited this as one of the key reasons they left Pakistan. A UN report also found that “returnee women were concerned about their children’s increasing difficulties going to school, stat[ing] they were prevented from attending school or [that] … schools in refugee communities were shut.”[65]

Human Rights Watch spoke with the headmaster of the Amina Fedawi High School for Afghan children in the Abdara neighborhood in Peshawar city. He told Human Rights Watch:

At the end of May, the police came and broke all our security cameras, took down our signs and told us to shut down the school, which we did. They said it was a federal government order and that all refugees had to leave Pakistan.

The police also shut down all but one of the other eight Afghan schools in our area. There were also eight in the Hayatabad neighborhood and only two stayed open. There were seven in the Afghan Kaluni neighborhood and five were closed. And the authorities also closed all three in the Takal neighborhood.

After the summer break, in early September, we tried to re-open the schools but the police came again and told us not to. They said we would face big problems if we opened them. We went to see the Afghan Consulate in Peshawar to complain but he said he couldn’t do anything.[66]

Police Theft and Unlawful Use of Force

Several returning refugees in Kabul and Afghans in Peshawar told Human Rights Watch that Pakistani police had slapped or beaten them when extorting money or stealing their possessions. Five others said that for the first time ever, police had stolen goods and trading tools worth thousands of rupees, effectively leaving them destitute, ending their ability to work, and convincing them it was time to leave Pakistan.[67]

A 30-year-old man living in the Board neighborhood in Tajabad, Peshawar city, said:

I was a cobbler and about six weeks ago [mid-September] the police took all my things and took me to the police station and then took all my money. Then they let me go. I didn’t have enough money to buy more tools to continue working. They confiscated the goods and tools of lots of street sellers in my area. Everyone had to stop working.[68]

Other Factors Driving Out Afghans

Returnees also described to Human Rights Watch other factors that contributed to their decision to leave Pakistan. Many feared that if they stayed, they would be forced back with nothing and without warning. Fearing destitution in Afghanistan, the doubling of the UNHCR cash grant to returnees was a critical factor their decision to leave. Additional factors included: anti-Afghan hostility by local Pakistani communities; Pakistani landlords suddenly charging significantly increased rent for apartments and business premises; the Afghan authorities’ promises to give returnees land; new border crossing restrictions preventing them from returning home for funerals or working in Afghan border areas; and the wish to follow relatives or even entire communities who had already returned and without whom they did not want to stay in Pakistan.

Cash Grant

In June 2016, UNHCR doubled its cash grant from $200 to $400 to each Afghan refugee returning from Pakistan, an average of $2,800 per family.[69] Numerous returning Afghan refugees told Human Rights Watch they would have been too poor to leave without UNHCR’s money. A 33-year-old man with seven children living in the Jalala camp in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province’s Mardan district said he was afraid that Pakistan would arrest and deport him without warning and thereby split him from his family. He said that he finally decided to leave because he was afraid that if he didn’t, he risked deportation alone and with nothing, instead of leaving with his family and almost $3,000.[70] Others fearing destitution in Afghanistan said that UNHCR money was their only hope of surviving after leaving Pakistan; and that without the money they would have remained in Pakistan and hoped the government would treat them better in 2017.[71]

Hostility from Pakistani Communities

Many returnees described how they had been welcomed for decades by local Pakistanis, but that after the killing of a Pakistani army major near the Afghan border in June 2016 they turned on them, telling them to go home and calling them “sons of Hindus,” referring to India’s increased ties with Afghanistan.[72] Large numbers of Afghans also described to the UN this shift in local Pakistanis attitude towards Afghans.[73]

Government Announcements Directing Pakistanis Not to Rent to Afghans and Increased Rent

Numerous Afghans said landlords evicted them from, or refused to rent, apartments or business premises after the Pakistani authorities announced in newspapers and on television that it was illegal to rent to Afghans.[74] Others said that beginning in July, landlords started doubling or tripling their rent, thereby forcing them out of their homes and businesses and leaving them destitute.[75]

Afghan Officials Promising Land for Returnees

On July 17, 2016, Afghanistan’s Ministry of Tribal Affairs and Afghan diplomats in Peshawar launched a special media campaign entitled “One’s Own Homeland,” which encouraged Afghans in Pakistan to return to Afghanistan. [76] Three weeks later, President Ghani’s Special Envoy and Ambassador to Pakistan said in an interview that the new campaign had produced “positive results” and that Afghans in Pakistan have “now … realized they should live in dignity in their own country.” He added that it was important that Afghanistan acted to prevent Pakistan from using refugees as “pressure buttons.”[77]

With funding support from UNHCR, on August 31, 2016, Afghanistan’s President Ghani met in Kabul with 120 Pakistan-based Afghan elders and other representatives.[78] The UN in Afghanistan reported that “the President pledged to ensure returning Afghans could obtain land and housing, invest in small businesses, send children to school, have access to basic services and settle in any part of the country.”[79] The president added he understood land was a key issue for returnees and “pledged to help returning families to legally obtain land and announced that five sites, with a combined settlement capacity of 50,000 families, had been identified to assist landless returnees or those not able or willing to return to areas of origin.”[80] During the meeting, Elham Omar Hotaki, whom the president has appointed to develop housing projects for refugees in Nangrahar and Kabul provinces, also said that “according to the President’s orders, returning families will be provided residential lands, drinking water, educational opportunities, health services and other facilities. We are fully prepared in this regard.’”[81]

In reality, no landless Afghan returning from Pakistan in 2016 received—or had the slightest prospect of receiving—any land in 2017.[82] UNHCR told Human Rights Watch that it “was … concerned about the Afghan government’s active promotion of return of Afghans from Pakistan, through the involvement of the President’s Special Envoy and Ambassador, community elders, and the holding of Jirgas [a traditional assembly of leaders]. We repeatedly advised the afghan government [to] refrain from making unrealistic pledges such as land allocation upon return.”[83]

Several returning Afghan refugees said that reports of the president’s promise had convinced them they would not face destitution on return to Afghanistan.[84] One man said:

Our [refugee] camp representatives told us we’d get land if we went back to Afghanistan. They showed us an interview on Facebook with Ashraf Ghani who said refugees coming home would get land. I believed him so we decided to leave.[85]

New Regulations Governing Afghans’ Cross-Border Movements

For decades, Pakistan has allowed Afghans to move back and forth across the border with Pakistan without any identity documents.[86] But on June 1, 2016, the authorities cited security concerns as grounds for introducing new measures requiring Afghans to hold passports, which cost about US$90, and visas to enter Pakistan.[87] A number of Afghans told Human Rights Watch that for years they had returned for brief periods to Afghanistan to attend funerals and other family events and that the new measures meant they would be split from relatives in Afghanistan.[88]

Relatives Leaving

Some returning Afghans said that the mass return of friends and relatives since July 2016 had left them feeling isolated in communities rife with anti-Afghan sentiment and police abuses and was instrumental in their decision to leave Pakistan.[89] UNHCR has also pointed out that “as undocumented Afghans are typically part of family units with PoR (Proof of Registration) cardholders, their registration would help to reduce pressures on PoR cardholders” to leave Pakistan if their undocumented relatives are deported.[90]

III. Forced Return of Refugees among Undocumented Afghans in Pakistan

Many Afghans crossing back and forth between Pakistan and Afghanistan are unlikely to be refugees and have no interest in lodging asylum claims in Pakistan. However, Pakistan’s refusal to register Afghan refugees after February 2007, and UNHCR’s inability to process large numbers of asylum seekers in Pakistan, means that many Afghans needing formal protection in Pakistan over the past 10 years have had no chance of obtaining it. This means Pakistan almost certainly, unlawfully coerced out significant numbers of people who may actually be refugees—de facto refugees—among the 205,000 undocumented Afghans who left Pakistan after June 2016 and who experienced the same Pakistani police abuses and deportation threats as registered refugees.

Undocumented Afghans in Pakistan

Since at least 2012, Pakistani authorities have estimated that there were about one million undocumented Afghans in the country, although they have given no basis for their estimate.[91] In the second half of 2016, just over 200,000 returned to Afghanistan.[92]

Pakistan’s only census of Afghans, in early 2005, identified 3,049,268 Afghans living in the country.[93] Of those, about one-fifth—582,535—returned to Afghanistan with UNHCR’s help before Pakistan began to register Afghans applying for Proof of Registration cards in October 2006. This left 2,466,733 eligible for cards. However, by the time registration closed in February 2007, only 2,153,088 Afghans had registered, leaving more than 313,000 unaccounted for.[94]

Afghans previously undocumented in Pakistan, who Human Rights Watch interviewed in Afghanistan in 2015, included many who had arrived in Pakistan in the 1980s or 1990s who said that they had not registered in 2006 and 2007 for various reasons, including: they thought doing so would make them more likely to be deported; they failed to understand the importance of obtaining documentation confirming their status in Pakistan; they were unable to respond to officials’ extortion demands; or they could not reach registration centers due to work and other obligations.[95]

Some portion of undocumented Afghans in Pakistan, including some of those who returned to Afghanistan in the second half of 2016, are likely economic migrants.[96] Some of those who did not register in 2007 have since returned to Afghanistan while others remained undocumented in Pakistan, together with Afghans who entered the country after February 2007.

Although technically in the county unlawfully, Pakistan mostly closed its eyes to undocumented Afghans’ presence until 2015.[97] Deportation numbers increased in 2012 to about 7,500, dipped again to less than 300 in 2013 and went back up to about 10,000 in 2014.[98] In 2015, the number doubled to just under 20,000.[99] In 2016, it was 22,559.[100]

The January 2015 National Action Plan, adopted after the Peshawar school attack, included a pledge to register all undocumented Afghans in the country in July and August 2015, although no such registration has taken place.[101]

In September 2016, the authorities announced that undocumented Afghans had until November 15, 2016 to voluntarily return to Afghanistan or face deportation.[102] The deadline passed with no action taken. In October 2015, UNHCR said that Afghanistan and Pakistan had agreed to jointly register undocumented Afghans in Pakistan and to issue them Afghan passports and Pakistani visas.[103] As of late January 2017, no such registration had taken place.[104]

Undocumented Afghans Returning to Afghanistan after June 2016

In recent years, relatively few undocumented Afghans left Pakistan. In 2013 and 2014, about 20,000 left each year, or about 1,800 a month.[105] In contrast, during the first half of 2015 alone, almost 82,000 returned, many fleeing widespread police abuses.[106] The numbers dropped significantly in the second half of the year and returned to the 2014 monthly rates by the last three months of the year. By the end of the 2015, just under 120,000 had returned.[107]

The low 2014 return rates continued for most of the first six months of 2016.[108] But in the third week of July 2016, the number of returns dramatically increased when over 6,000 returned.[109] By December 31, a total of 225,630 had returned since the start of the year, 91 percent of whom returned since the July increase.[110] Repeating language used throughout the second half of 2016, in early January 2017, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) summarized the cause of the 2016 increase as “diverse push factors, including deteriorating protection space in Pakistan.”[111]

Likely Refugees among Undocumented Afghans Unable to Obtain Protection

UNHCR considers those Afghans the government of Pakistan registered and issued with Proof of Registration cards in late 2006 and early 2007 to be refugees simply because of their nationality—that is, they were and continue to be recognized as refugees on a prima facie basis.[112] Senior Pakistani officials also refer to them as refugees.[113]

Afghans in Pakistan who did not register in 2006 and 2007, or who arrived after registration ended in February 2007, share the same general profile as the Afghans who registered before the cut-off date. They either fled Afghanistan between 1978 and 2007, or left Afghanistan after 2007 for a range of reasons comparable to those who left the country after the fall of the Taliban government in late 2001. This group likely includes both economic migrants and refugees. However, Pakistan does not have an asylum system to adjudicate individual claims. This means the Pakistani government changed its policy overnight in February 2007 from essentially recognizing all Afghans without differentiation as refugees to not recognizing any more as refugees.[114]

In many other countries without asylum procedures, UNHCR reviews asylum applications through Refugee Status Determination (RSD) procedures. The main purpose of RSD operations in Pakistan is for UNHCR to identify especially vulnerable Afghans among the undocumented population who cannot remain in Pakistan and who need to be recognized officially as refugees in order to be resettled in other countries.[115]

UNHCR also reviews asylum claims by Afghans who do not require resettlement, but who approach UNHCR for protection and who may qualify as refugees under the 1951 Refugee Convention.[116] However, unlike in many other parts of the world where asylum seekers file claims with UNHCR in the tens of thousands, UNHCR in Pakistan has only very limited capacity to process such claims. In order to reduce pressure on UNHCR’s limited resources, nongovernmental organizations working with UNHCR screen Afghans who approach UNHCR for protection and identify “manifestly unfounded” claims that can be quickly rejected.[117] These limitations mean Afghans in Pakistan approach UNHCR in relatively small numbers.[118]

The combination of Pakistan’s refusal to register Afghans seeking protection after 2007 and UNHCR’s inability to take over that role means unknown numbers of de facto Afghan refugees are currently excluded from obtaining protection in Pakistan.

Pakistan is obliged under international law not to return anyone in any manner to threats of persecution, torture, and other serious harm, and deporting undocumented Afghans without any recourse to protection procedures therefore also risks refoulement.[119] Because Pakistani police abuses documented in this report have driven out large numbers of undocumented Afghans as well as registered refugees, Pakistan has likely committed mass refoulement of de facto refugees among the population of undocumented Afghans.

To address this problem, Pakistan could do one of two things. Either it could swiftly open registration for asylum seekers among undocumented Afghans in Pakistan who are seeking protection, regardless of whether that leads to refugee status on a prima facie basis (i.e. based simply on nationality) or a comparable blanket form of temporary protection. Or it could mount a sustained public information campaign informing undocumented Afghans, including those in detention and faced with imminent deportation, that they are entitled to register refugee claims with UNHCR and how to do so.

Absent such policies and procedures, any further deportation deadlines and police abuses driving out undocumented Afghans will result in further refoulement of unregistered refugees among them and of their registered, dependent relatives who will feel they have no option but to leave with them.[120]

IV. UNHCR’s Response to Pakistan’s Mass Refoulement

UNHCR has been facilitating the voluntary repatriation of Afghan refugees from Pakistan since 2002. Before the hike in Pakistani police abuses against Afghans in early 2015, Afghan refugees’ decisions to return home were, for the most part, voluntary.

Under pressure from the Pakistani authorities, which wanted to see increased repatriation rates, UNHCR doubled its cash support in June 2016 to returning Afghan refugees. For many, already faced with deportation deadlines and police abuses, this was the tipping point to return to Afghanistan. By the end of December 2016, almost 365,000 registered refugees had returned during the world’s largest recent case of mass refoulement.

Throughout the returns, UNHCR referred to its “voluntary repatriation” operations and failed to call for an end to Pakistan’s coerced refugee return. UNHCR’s involvement in not only facilitating but also promoting involuntary refugee repatriation through significant cash support to returnees without calling the situation refoulement contradicted its basic refugee protection mandate and made it complicit in Pakistan’s mass refoulement of Afghan refugees.

In early November 2016, citing donor shortfalls, UNHCR said it would suspend cash support to returnees as of mid-December, but said it would resume support on March 1, 2017. If the Pakistani authorities do not end their threats to deport Afghan refugees after Proof of Registration cards expire on March 31, 2017 and continue to tolerate widespread police abuses against Afghans, large numbers of Afghans will likely continue to be coerced into leaving. If UNHCR continues its cash support to returnees without making clear that many of them are being driven out of Pakistan unlawfully, UNHCR will remain complicit in the refoulement of Afghan refugees in 2017.

Supporting the Voluntary Repatriation of Afghan Refugees from Pakistan

Four months after the defeat of the Taliban government in November 2001, UNHCR began helping Afghans return home on an ad hoc basis. By the end of 2002, the agency had facilitated the return of about 1.5 million Afghans from Pakistan and publicly called on the authorities to end incidents of forced return.[121] In March 2003, UNHCR signed the Tripartite Agreement Governing the Repatriation of Afghan Citizens Living in Pakistan (the “Tripartite Agreement”) with Afghanistan and Pakistan to provide a legal and operational framework for voluntary refugee returns.[122] Between 2003 and 2008, UNHCR helped 1,930,068 Afghans return home, an average of about 320,000 a year.[123] Reflecting the deteriorating security situation in Afghanistan, a yearly average of only about 70,000 returned over the ensuing four years.[124] The Pakistani authorities will have been aware that the estimated 60,000 children born to Afghan refugees in Pakistan each year meant the decreased return numbers were in effect resulting in a stable number of Afghan refugees living in Pakistan.[125]

UNHCR’s Response to Decreasing Refugee Returns

In response to the plummeting numbers of refugees returning, Afghanistan, Iran, Pakistan, UNHCR, and delegates from about 40 countries endorsed a Solutions Strategy for Afghan Refugees in May 2012.[126] The strategy aims to “assist host countries” and “support voluntary repatriation and sustainable reintegration” of Afghan refugees back home in the medium term by going beyond basic humanitarian assistance and helping them “access shelter … essential social services [and] improved and diversified livelihood opportunities and enhanced food security.”[127]

Over the next two years, increased insecurity and “the complex political situation” in Afghanistan resulted in the strategy making little progress.[128] In the meantime, the rate at which Afghan refugees returned from Pakistan continued to drop in 2013 to about 30,000 and hit a low of about 12,300 in 2014.[129]

Despite the deteriorating security conditions in Afghanistan as well as Pakistani police abuses against Afghans at the time, UNHCR, at a Tripartite Agreement meeting with Afghanistan and Pakistan in March 2015, committed to helping the two countries raise money to implement a new “enhanced voluntary return and reintegration package.”[130]

UNHCR proposed to “incentivize return” and “mitigate the negative consequences of unprepared return” by complementing the $200 UNHCR cash grant for returning refugees with a $3,000 grant for each family, irrespective of size. UNHCR said the initiative was based on the “historical[ly] low” return numbers in 2013 and 2014, the need to address Pakistan’s “legitimate expectations to see increased voluntary return trends in the near future [and] a sense of asylum fatigue [and] dwindling donor support,” and on a claim that “the majority of Afghan refugees have cited economic concerns, lack of livelihoods, land, shelter and limited access to basic services in Afghanistan as the main obstacles to return.” The document also said that “the positive developments in Afghanistan” in 2014 meant the country was now entering “a landmark year” and “a new chapter in its history,” which provided “an unprecedented impetus to … support the fulfilment of the aspirations of Afghans outside their country to exercise their legitimate ‘right to return.’”[131]

UNHCR’s proposal fell on deaf donor ears and was never implemented, yet despite the deteriorating security situation in Afghanistan, the language reflects UNHCR’s intention to use enhanced return support to encourage more Afghan refugees to repatriate from Pakistan.

Doubling the Cash Grant to Returning Refugees

Pakistani police abuses in the first half of 2015 fueled the return of large numbers of Afghan refugees, but the numbers decreased again in the second half of the year and returned to a trickle in the first half of 2016 with only 6,875 returning.[132]

At the end of June 2016, Filippo Grandi visited Islamabad, his first destination as the refugee agency’s new high commissioner.[133] According to a senior UN official, Pakistani officials frustrated about the low return numbers told him that if UNHCR wanted Pakistan to extend Afghan refugees’ Proof of Registration cards for a further six months, the international community needed to help Pakistan deal with its Afghan refugee burden. They cited by way of example the European Union’s €3 billion deal with Turkey to host Syrian refugees and prevent them from boarding boats to Greece.[134]

On June 29, UNHCR announced it was doubling its cash support to returning Afghan refugees to $400, including average transportation costs.[135] The rate of increase was significant compared to previous increases. [136] It also meant that the average family, with seven members, would receive $2,800, a significant amount of money for impoverished Afghans.[137]

A senior UN official told Human Rights Watch that UNHCR took the decision to double the grant in exchange for a promise by the Pakistani authorities to extend Afghan refugees’ status in Pakistan until the end of 2016, saying UNHCR was “literally buying protection space.”[138] The same day—a day before Pakistan’s deadline for deporting Afghan refugees was due to kick in—the authorities extended Afghans refugees’ status for a further six months, until December 31.[139]

Many returning Afghan refugees told Human Rights Watch that UNHCR’s cash handout was an important factor in their decision to return after Pakistani police abuses started.[140]

This cash “pull factor” effect should not have been surprising to UNHCR, which knew from a 2009 study it commissioned into the impact of UNHCR’s cash grant to Afghan refugees returning home from Iran and Pakistan what level of support would incentivize greater numbers of Afghan refugees to leave Pakistan.[141]

The study found that “returnees from Iran were rather less dependent on the grant than returnees from Pakistan, supporting the widely held belief that refugees living in Pakistan are more vulnerable than the refugees living in Iran;” that “nearly half the returnees relied heavily on the cash grant to return;” that “80% of the families who did not return were prevented [from doing] so because of [a] lack of social and physical assets in Afghanistan” and that those families “suggested a grant between $300 and $400 would be more effective at enticing them to return;” that non-cash support was not likely to “be either as efficient as the cash grant system, or encourage the same levels of return;” that “the cash grant is in many cases enabling refugees, who do not have existing social or physical assets in Afghanistan, to make the move to return home” but that they “regard the $100 on average per person offered as insufficient to counter the high risk of returning, especially in situations where returning families do not have family, houses or land in Afghanistan;” and, in conclusion, that “UNHCR should consider the impact of raising the cash grant up to higher levels, which may prove to be enticing enough to encourage the remaining refugee families, often who do not have social or physical assets in Afghanistan, to return.”[142]

In 2014, UNHCR concluded that “more than 30% of Afghan returnees in 2014 cited UNHCR assistance packages as a pull factor to return.”[143]

Although Pakistan’s police had not yet unleashed their latest round of abuses against Afghans, UNHCR had good reason to be skeptical of the conditions in Afghanistan to which Afghan refugees responding to its increased June 2016 cash grant incentive would return.

According to a July 2016 UNHCR report, which was drafted before increased numbers of Afghans started fleeing police abuses in mid-July, “rapidly deteriorating security in most parts of Afghanistan” had killed more civilians than at any time since 2009 and triggered “unprecedented” internal displacement which meant the country had “reverted back to a humanitarian emergency” and “dire socio-economic conditions” that the “humanitarian community is severely constrained in addressing … due to increasing insecurity and … dwindling resources.”[144]

UNHCR’s Complicity in Mass Forced Refugee Return in the Second Half of 2016

UNHCR Rules on Voluntary Return

Since signing the 2003 Tripartite Agreement with Afghanistan and Pakistan, UNHCR has facilitated the return of millions of Afghan refugees, which its “Handbook on Voluntary Repatriation” (“the Handbook”) says the agency may only do if repatriation is voluntary in nature.[145]

The Handbook sets out two clear conditions for repatriation to be considered voluntary.

First, whether a return is voluntary “must be viewed in relation to … conditions in the country of origin (calling for an informed decision).” UNHCR should not promote or facilitate refugee return based on presumptions about how well-informed refugees are about conditions in the home country. It has a responsibility to ensure that refugees are making an informed choice based on up-to-date, objective, and accurate information about security conditions and availability of assistance to reintegrate in their home country. The Handbook spells out that:

information campaigns are UNHCR's core responsibility and principal mechanism to promote voluntary repatriation and to ensure that refugees' decisions are taken in full knowledge of the facts. Where UNHCR is only facilitating (spontaneous) repatriation, information campaigns with a view to promoting voluntary repatriation are not normally appropriate. However, the provision of accurate and objective information on the situation in the country of origin by UNHCR will be an important activity.[146]

It goes on to list various methods UNHCR may use when facilitating refugee return to ensure refugees are informed about what they face back home.

Second, whether a return is voluntary “must be viewed in relation to … the situation in the country of asylum (permitting a free choice).”[147]

[Refugees] need to know about what will happen in the event they decide not to volunteer for repatriation” and that “repatriation is not voluntary when host country authorities deprive refugees of any real freedom of choice through outright coercion or measures such as, for example, reducing essential services [and] encouraging anti-refugee sentiment on the part of the local population. [148]

In addition,

one of the most important elements in [UNHCR’s] verification of voluntariness is the legal status of the refugees in the country of asylum. If refugees are legally recognized as such, their rights are protected and if they are allowed to settle, their choice to repatriate is likely to be truly free and voluntary. If, however, their rights are not recognized, if they are subjected to pressures and restrictions …they may choose to return, but this is not an act of free will.[149]

The Handbook says that before concluding refugees are returning voluntarily, UNHCR must “be convinced that the positive pull-factors in the country of origin [i.e. security and assistance] are an overriding element in the refugees' decision to return rather than possible push-factors in the host country [i.e. pressure to leave].”[150]

The Handbook adds that where UNHCR is not convinced returns are voluntary, “it is essential to declare clearly to the authorities concerned that UNHCR is opposed to the action and to seek corrective measures. This should be done both in the field and at Headquarters and, if necessary, at the highest level through the intervention of the High Commissioner.”[151]

The Handbook also says UNHCR may “facilitate” or “promote” voluntary repatriation.

It says UNHCR may facilitate return “when refugees indicate a strong desire to return voluntarily and/or have begun to do so on their own initiative, even where UNHCR does not consider that, objectively, it is safe for most refugees to return,” but that “this term should be used only when UNHCR is satisfied that refugees' wish to return is indeed voluntary and not driven by coercion.”[152] It adds that if UNHCR does facilitate voluntary repatriation, it should only “provide those returning with limited material assistance for their return,” to avoid creating too much of a pull factor that overly encourages refugees to return to unsafe conditions and plays into the hands of authorities coercing out refugees.[153]

The Handbook says UNHCR may go one step further than facilitation and actively “promote” voluntary repatriation by “actively undertaking broad and wide-ranging measures to advocate refugees' return,” but that it may only do so “when a careful assessment of the situation shows that the conditions of [return in] "safety and dignity" can be met: in other words, when it appears that objectively, it is safe for most refugees to return and that such returns have good prospects of being durable.”[154]

It warns that “voluntary repatriation is not a durable solution in the absence of the returnees' reintegration into the local community,” which it defines as “a gradual process often paralleled, over years, by national reconciliation and improvements in the economic, social and human rights fields.”[155] It also clarifies that UNHCR “has competence” for refugees after they have repatriated with UNHCR’s help because of the agency’s “general mandate to seek voluntary repatriation as a durable solution for refugees” and “recommends … UNHCR formulate a country- and area-specific Reintegration Programme Strategy which specifies the criteria and programme priorities in the area of reintegration.”[156] The Handbook further states that even if return leads to durable reintegration into local communities, “essential preconditionsto be met for UNHCR to promote voluntary repatriation movements” include that “all parties must be committed to fully respect its voluntary character.”[157]

The Tripartite Agreement commits Afghanistan, Pakistan and UNHCR to “cooperate to facilitate and assist the voluntary repatriation … of Afghan[s]” and commits UNHCR to playing a “supervisory role in promoting, facilitating, coordinating and monitoring the voluntary repatriation of Afghan citizens in order to ensure that repatriation is voluntary and carried out in conditions of safety and dignity.”[158]

UNHCR’s Failure to Criticize Pakistan’s Coerced Refugee Return

Until early 2015, the voluntary nature of most Afghan returns from Pakistan was not called into question. Pakistan’s police abuses in the first half of 2015 triggered a new spike of 58,000 refugee returns, up from 12,300 the year before. These abuses may have pushed many of the returnees to leave Pakistan and this would have amounted to coerced return and therefore refoulement.

But beginning in late June 2016, it became clear that the level of abuses, insecure legal status and related government deportation threats stripped countless Afghan refugees of any real choice, but to leave Pakistan. From July through December, 363,227 registered Afghan refugees returned to Afghanistan from Pakistan, with 145,955 returning during the month of October alone and only 135 returning in December.[159]

During this time, UNHCR failed to call for an end to coercive government practices, not once publicly stating that many returning refugees were primarily fleeing police abuses and fear of deportation and were therefore victims of large-scale refoulement. Instead, UNHCR merely reiterated its October 2015 plan to “continue to facilitate returns in safety and dignity, monitor their voluntary nature … and raise concerns as necessary with the relevant [Pakistani] counterparts.”[160]

UNHCR told Human Rights Watch in late October 2016 that returning Afghan refugees told its staff in Kabul about Pakistan police abuses and other factors that drove them out of Pakistan. UNHCR said that its office in Islamabad “raises their concerns with the Pakistani authorities.”[161]

UNHCR’s protection mandate requires it to raise protection concerns with governments abusing refugee rights, including, as in the case of Pakistan in 2016, police violence, extortion, arbitrary detention, harassment and denial of access to education.[162]

However, UNHCR’s decision not to criticize Pakistan’s coercion of refugees meant its discrete behind-the-scenes interventions on individual abuse cases or localized abuses were woefully inadequate to end the widespread abuses affecting hundreds of thousands of Afghans and which continued unabated for at least three months.

In contrast to its claim to Human Rights Watch that the agency conducted closed-door advocacy with the government of Pakistan during the second half of 2016, UNHCR consistently referred publicly to its “facilitation” of “voluntary repatriation” of Afghan refugees.[163] In early September, seven weeks after the abusive returns began, UNHCR announced it was opening a new voluntary repatriation center in Peshawar to help cope with the massive numbers of returnees.[164]

UNHCR also used convoluted language in statistical updates and other documents with low public circulation to avoid labeling Pakistan’s coercion of refugees’ return as “refoulement.”

On June 23, 2016, UNHCR made its most critical statement of Pakistan to date, saying “there is now a concerted push from the Pakistan government to repatriate a large number of … almost one million refugees.”[165] In early September, UNHCR signed onto a donor appeal that said there had been a “dramatic rise in push factors … influencing return decision-making” and that the “sudden increase in return was not anticipated by humanitarian agencies and has coincided with the drastic deterioration in the protection and political environment for Afghans within Pakistan, both Proof of Residency [sic] (PoR) card-holders and the undocumented.”[166]

And writing in a personal capacity in a UN inter-agency document, in September, UNHCR’s representative in Afghanistan said that the massive increase in returning Afghans, including refugees, was due to “a dramatic increase in push factors, in the form of increased extortion, harassment and intimidation by local officials, contraction of freedom of movement and a subsequent limitation on income generation activities, … a wave of anti-Afghan sentiment within Pakistan ... and a dramatic worsening of longstanding protective relations within host communities.”[167]

In a further donor appeal in late October, UNHCR listed a number of non-coercive factors explaining why refugees might be returning, adding that other factors included the fact that “refugees remain anxious about what may happen” when their Proof of Registration cards expire at the end of March 2017 and that “a number of returning refugees continue to cite incidents of harassment and detention.” UNHCR added that “these dynamics underscore the critical differences of the current population flows with return patterns in previous years.”[168]

On November 6, UNHCR noted that “push factors” and “the protection situation” meant there had been a “changing dynamic” and an “unexpected exponential return of Afghans in difficult circumstances since July,” which returnees described as “a lack of labour opportunities and … self-imposed restriction of movement … due to police harassment and changing attitude of locals, hosting communities and local authorities, [the] possible suspension of UNHCR’s assistance, [fear] of arrest or intimidation … and the uncertainty of the renewal of [Proof of Registration] cards beyond March 2017.” The document added that “reports of harassments tend to be minimal and the decision for return is reportedly preventive, i.e. to avoid the effects of a possible deterioration of the situation.”[169]

On November 10, UNHCR responded to media inquiries about whether the agency agreed that Pakistan was illegally forcing out Afghan refugees by saying that “the return of registered Afghan refugees from Pakistan is a repatriation in less than ideal circumstances and is the result of a number of factors.”[170] The agency didn’t elaborate on those factors or whether it regarded “less than ideal circumstances” as a violation of Pakistan’s obligations.

In late November, UNHCR’s Afghanistan representative said that there was “a crisis of protection in Pakistan, in the sense of the level of harassment, intimidation and lack of support from host communities,” but went no further.[171]

UNHCR also did not state that Pakistan’s abuses and the resulting coerced return of Afghan refugees violated Pakistan’s obligations under the Tripartite Agreement to ensure that Afghans return voluntarily to their country. UNHCR thereby was acting in violation of its own supervisory obligation under the Tripartite Agreement to ensure that repatriation was voluntary in nature.

UNHCR’s decision not to criticize the Pakistani authorities’ coercion of Afghan refugees into leaving the country has frustrated some of its more junior staff in the region. In early November, the head of UNHCR’s sub-office in the Afghan border town of Jalalabad told the media, “I personally don’t see this as a voluntary repatriation … When you are harassed, intimidated, rounded up by police, taken to court, forced to pay bribes, you are being forced to leave.”[172] At the end of November, one of UNHCR’s repatriation assistants in Kabul said: “We call these people ‘voluntary returnees,’ but they really don't have a choice - this is not voluntary.”[173]

UNHCR’s Promotion of Involuntary Refugee Return