(Ramallah) – The Palestinian authorities in the West Bank and Gaza are arresting, abusing, and criminally charging journalists and activists who express peaceful criticism of the authorities. The crackdown directly violates obligations that Palestine recently assumed in ratifying international treaties protecting free speech.

“Both Palestinian governments, operating independently, have apparently arrived at similar methods of harassment, intimidation and physical abuse of anyone who dares criticize them,” said Sari Bashi, Israel and Palestine country director at Human Rights Watch. “The Palestinian people fought hard to gain the protections that accompany membership in the international community, and their leaders should take their treaty obligations seriously.”

Human Rights Watch documented five cases – two in the West Bank and three in Gaza – in which security forces arrested or questioned journalists, a political activist, and two rap musicians based on their peaceful criticism of the authorities. Four of those arrested, two in Gaza and two in the West Bank, say that security forces physically abused or tortured them. The authorities in Gaza denied the allegations, and in the West Bank the authorities said they could not investigate the allegations in the absence of a formal complaint. These crackdowns follow a pattern of violations of the right to free speech and due process that Human Rights Watch has documented in the past five years, most recently in May 2015. In the West Bank, some progress has been made in protecting the rights of those arrested.

In Gaza, Hamas authorities detained and intimidated an activist who criticized the government for failing to protect a man with a mental disability; a journalist who posted a photograph of a woman looking for food in a garbage bin; and a journalist who alleged medical malpractice at a public hospital after a newborn baby died. In the West Bank, the Palestinian Authority (PA) arrested and charged activists and musicians who ridiculed Palestinian security forces for cooperating with Israel and accused the government of corruption. The offending statements were allegedly made in Facebook postings, graffiti, and rap songs.

In the abuse cases, activists and journalists said that security officers beat or kicked them, deprived them of sleep and proper food, hosed them with cold and then hot water, and made them maintain uncomfortable positions for long hours. In Gaza, two detainees said security officials made them sign commitments not to criticize the authorities without proper evidence. In the West Bank, both men arrested faced criminal charges, including defamation and insulting a public official.

These crackdowns on free speech and the use of torture violate the legal commitments that the PA assumed in 2014, when it ratified the International Convention on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the Convention Against Torture. They also violate provisions of the Palestinian Basic Law protecting speech. At a time when many Palestinians are critical of their leaders, the crackdowns have a chilling effect on public debate in the traditional news media, and on social media. These leaders have remained in power for a decade with no elections planned following a split that left Hamas controlling Gaza and the Fatah-dominated PA controlling the West Bank.

In 2011, Human Rights Watch issued a report on violations of media freedoms by the PA and Hamas. The report cited the work of Palestinian watchdog groups like the statutorily created Independent Commission for Human Rights (ICHR) and the Palestinian Center for Development and Media Freedoms (MADA) and criticized the PA for using military proceedings to detain civilian journalists or detaining civilians with no judicial process, in violation of Palestinian law.

Since then, the PA has stopped trying civilians in military courts, an important step toward protecting their rights. However, the ICHR told Human Rights Watch that the PA stepped up its use of the civilian public prosecution to bring formal changes against journalists for so-called crimes such as libel or “insulting a higher authority,” a relic from the pre-1967 penal code enforced in Gaza and the West Bank by Egypt and Jordan respectively.

Lawyers and those arrested say that in the West Bank, authorities use court proceedings as harassment. Prosecution witnesses routinely fail to appear, and judges grant multiple adjournments, requiring the accused to return to court repeatedly, at the expense of their work and studies. While the increasing use of the judicial process to address alleged criminal violations is an important sign of progress, the PA’s reliance on archaic laws punishing speech is a source of concern, Human Rights Watch said.

The media freedom group MADA documented 192 incidents in 2015 in which Palestinian authorities infringed on journalists’ right to free expression through summoning and interrogation, arrests, physical assault, detention, and, in Gaza, forbidding journalists from reporting on certain issues or stories. That was a 68 percent increase over 2014. The pattern of abuse that MADA reported, including beatings, torture, warnings to stop criticizing the government, and seizing passwords to search social media accounts, is consistent with the cases Human Rights Watch documented.

Since 2007, Palestinian journalists have often reflected the split between Fatah and Hamas. MADA said: “The internal Palestinian division continues to be one of the key reasons behind the Palestinian violations against media freedoms … especially when it comes to the freedom of media outlets affiliated to a certain party.”

The Independent Commission for Human Rights reported that 24 people in the West Bank and 21 in Gaza were arrested in 2015 for criticizing Palestinian authorities, including on Facebook, or covering topics deemed forbidden.

Palestinian journalists also face abuse and harassment from Israeli soldiers, who have beaten them at demonstrations, closed media offices, and arrested journalists for posing unspecified security risks. During escalations of violence, Israel has assassinated journalists affiliated with armed groups in Gaza, alleging that their affiliation makes them a legitimate target.

Representatives of the Hamas government in Gaza denied the allegations of physical abuse and told Human Rights Watch that security forces do not arrest people based on their opinions, but rather only if they break laws against defamation or incitement to violence.

Palestinian Authority officials in the West Bank said that they were working to comply with Palestine’s new international commitments, but that the transition was not complete. They did not address allegations of misuse of prosecutorial discretion and abuse by security forces in the cases that Human Rights Watch documented.

The international rights standards Palestine adopted bar criminal defamation. The UN Human Rights Committee, which interprets the ICCPR, has stated that freedom of expression standards require that public officials should be subject to greater criticism than others.

The Palestinian penal code should be revised to eliminate criminal defamation, and any provisions that criminalize insulting public officials, Human Rights Watch said. Pending those revisions, security officers and prosecutors should refrain from enforcing criminal defamation laws and stop arresting people based on their speech and writing. Authorities in Gaza and the West Bank should take measures to prevent abuse by security forces and should investigate and prosecute those responsible.

“In the absence of elections, Palestinians are stuck with the same leaders who took power a decade ago,” Bashi said. “At the very least, those leaders should listen to criticism, not punish it.”

Methodology:

Human Rights Watch interviewed five journalists, activists, and musicians, three in Gaza and two in the West Bank, who said security officers arrested and interrogated them about their criticisms of the authorities. Human Rights Watch spoke to the lawyers representing the two individuals in the West Bank in criminal cases brought against them and reviewed court documents. In Gaza, Human Rights Watch reviewed police summons and posts that those arrested had published on social media. Human Rights Watch also interviewed the head of the ICHR and reviewed its reports and those of MADA. Human Rights Watch conducted telephone interviews with representatives of the authorities in Gaza and in-person meetings with the authorities in the West Bank. Human Rights Watch also re-interviewed two students whose arrest it documented in May 2015, spoke to their lawyers and reviewed court documents in their cases.

Gaza

Ayman al-Aloul

Ayman al-Aloul worked as a journalist for Iraqi and Gulf-based television stations and is also a civil servant, receiving a salary from the Fatah-controlled Palestinian Authority (PA), the Hamas rival. Al-Aloul said that on the evening of January 3, 2016, men who identified themselves as security officials arrested him at his home in Gaza City, confiscated his cell phone and two laptop computers, and took him to Gaza’s Ansar prison. Interrogators ordered him to reveal the passwords for his social media accounts and cell phone, which they searched.

Referring to his postings, they accused him of distorting Hamas’s image, he said. They also asked him about a photograph he posted on Facebook showing a woman looking through a garbage bin for food and a post critical of Hamas for failing to stop a man from walking into Egypt for medical treatment after he failed to receive permission to leave Gaza, whose borders are mostly closed. Egyptian soldiers shot and killed him. Al-Aloul also said the interrogators asked him about an interview he gave to al-Aqsa Television, affiliated with Hamas, in which he responded to allegations that the PA is paying him to criticize Hamas. In response, he had said sarcastically, “If any one of you (Hamas) pays me, I promise to shut my mouth. How could I shut up without anyone paying me a shekel?!” Referring to that comment, his interrogators accused him of extortion.

He said that interrogators blindfolded him and made him sit for hours in a child’s chair, in a cold room, without proper clothing or food, then repeatedly slapped him on the back of his neck and accused him of being a foreign agent. On the second day of his interrogation, they transferred him to the military prosecution, where security officers told him he could ask for a lawyer but that it was not necessary. Al-Aloul said he agreed not to request a lawyer. They held him for eight days, allowing visits on the last day from the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and local Palestinian human rights organizations.

Security officers released him on January 11, after making him sign a commitment not to deviate from custom, tradition, and Islamic law, to be respectful, and to conform to behavioral norms. They did not give al-Aloul a copy.

Security officials apparently continued to monitor his writings and speech, he said, and sent him warnings to stop working as a journalist. Al-Aloul said that a colleague at an office from which he had worked told him that someone who identified himself as representing the internal security service called him and told him not to allow al-Aloul to continue working out of his office space. Another friend of al-Aloul, Nihad Nashwan, who has professional dealings with Gaza’s Internal Security service, told Human Rights Watch that, at a meeting unrelated to al-Aloul’s case, after al-Aloul’s release, Abu Khaled Oda, the head of internal security, told him to tell al-Aloul to stop working as a journalist.

Al-Aloul said that since his detention, he has moderated his criticism of Hamas but continues to comment on Facebook. He said he received warnings from people he did not know, in response to Facebook postings critical of Hamas, and that he assumed those warnings, some of which referred to his detention, came from the security forces. After posting a comment on February 25, referring to an internal dispute between Hamas’s military and political branches, he received a comment that he “seems to be itching for another injury.” On April 18, after a post in which he criticized the government for compensating the families of those killed by Israel but not supporting ordinary people in need, he received a comment on Facebook, also from someone he does not know, saying, “Mr. Ayman! Won’t you stop talking about such issues? Did you forget your commitment before being released from Ansar Prison?”

Ramzi Herzallah

Ramzi Herzallah is a 28-year-old employee of a currency exchange business who belonged to Hamas’s armed wing until 2011, when he ended his Hamas affiliation. On January 1, 2016, officials at the public prosecutor’s office summoned him and told him that the Interior Ministry had filed a complaint, alleging that he had slandered ministry officials over Facebook. The offending post was a video in which Herzallah criticized Hamas authorities for the case that al-Aloul had discussed, in which security officers failed to prevent a man from crossing the Gaza-Egypt border without permission. After a few hours, officials released Herzallah.

Two days later, at about 6 p.m., five uniformed men arrived at his house in Gaza City and identified themselves as members of the internal security apparatus, he said. They produced search and arrest warrants and searched his house. They confiscated two of his computers and a cellphone, blindfolded him, and took him to Ansar Prison, refusing to give the reason for his arrest. Men he could not identify then repeatedly slapped his face, until security officers removed his blindfold and took him to a room to await interrogation.

At 4 a.m., masked interrogators arrived and accused him of collaborating with the rival Fatah faction and Egyptian intelligence. The interrogators demanded his social media passwords, then told him they were deactivating his Facebook account to prevent discussion of his arrest there. They ordered him to unlock his cell phone.

Herzallah said that they also made him sit in a child’s chair, where he spent three days with only brief bathroom breaks. They gave him food, but if he fell asleep, interrogators would slap him awake. Interrogators accused him of a pro-Fatah bias, opened his laptop, asked him about the source of some of his Facebook posts, and slapped him and pushed his head against a wall when he argued with them over his writing.

Herzallah said they permitted him to request a lawyer but he declined, saying that he was defending the population of Gaza by writing critically about issues and that he could defend himself, too. He said that initially authorities refused to allow human rights organizations to visit him, but on the seventh day, he received visits from the ICRC and the ICHR. They permitted his family to visit him the following day.

They released him on January 11, telling him that while he could express criticism, he could not insult the government, and had to report back to internal security in two weeks.

For the next week, he said, he refrained from making public statements or postings of a political nature. He reported back to internal security about two weeks after his release, together with Ayman al-Aloul with whom he is friendly, and at the meeting security officials warned him that they are monitoring his Facebook account.

Herzallah said he was told to sign two documents during his detention: a confirmation that officials were charging him with “harming revolutionary unity” and a commitment, upon his release, not to insult government officials. He did not receive copies of either document, and has not been approached by security forces since.

Mousheera al-Haj

Mousheera al-Haj is a Palestinian journalist who until recently edited the news website Bawabet Alhadaf, which is affiliated with the Palestinian faction the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. On April 14, 2014, she posted on her Facebook page a response to an incident in which a newborn baby died at a public hospital in Gaza. In the post, she blamed the doctors for the baby’s death, writing, “of what guilt was she killed, you son of dogs!” Nearly a year later, on March 28, 2015, she wrote an article on the website criticizing the Health Ministry for setting a qualifying exam for dentistry graduates that most failed.

Two weeks later, on April 9, her husband was summoned to the Sheikh Redwan police station. The summons, which Human Rights Watch viewed, did not specify the reason. She said that when her husband arrived at the police station, officials there told him that the prosecutor wanted to question her about the post she had written on Facebook in 2014. She went to the police station that same day and was questioned for about an hour about the Facebook post.

Ten days later, security officials called her husband again and told him that she should report to the police station. The interrogator told her to apologize to the Health Ministry and that she was being questioned on the charge of “insult and defamation.” Al-Haj said she refused to apologize.

On August 5, interrogators called her husband and told him she must again report to the police station. Al-Haj said interrogators questioned her briefly and then asked her to publicly apologize for the post. When she refused, security officers took her to Ansar Prison, where they conducted a body-search and detained her for about four hours. She said they allowed her to receive visitors from local human rights organizations and the ICHR.

Al-Haj said she eventually told interrogators she would apologize “in my way”, and they released her in the afternoon. That same day she wrote on Facebook to thank those who supported her during her detention and to say that her shock, as a mother, at the baby’s death, led her to write harshly about the hospital incident.

West Bank

Mutaz Abu Lihi

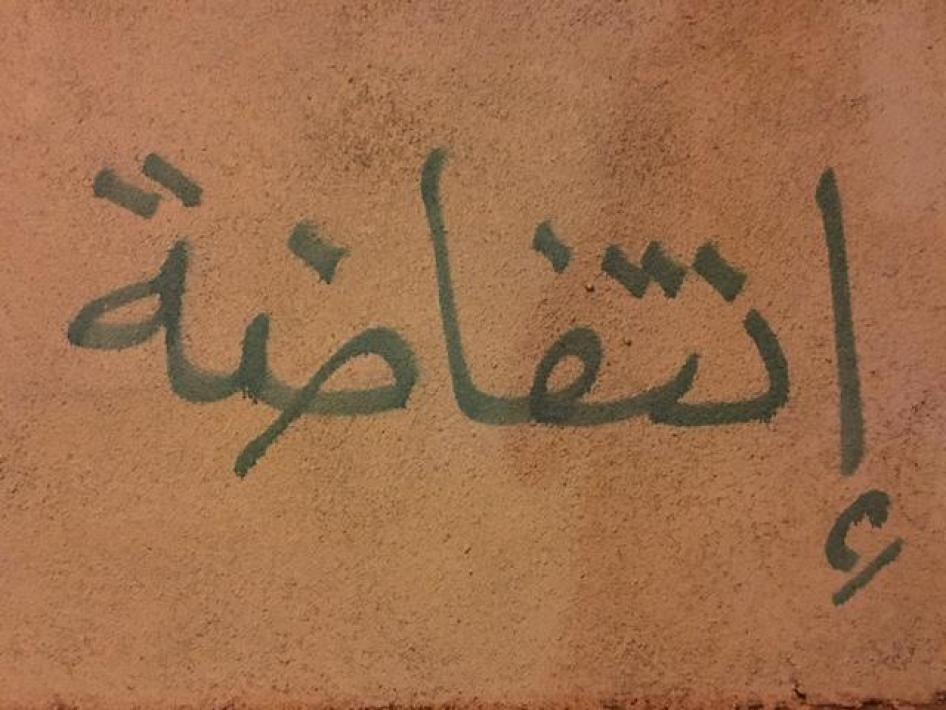

Mutaz Abu Lihi is a 21-year-old media student at Al Quds University in the West Bank and a former member of the rap group Min al-Alef Lal Ya (“From A to Z”). On the morning of November 21, 2014, he said, Palestinian security officials took him from his home to intelligence agency headquarters. They asked him questions about his political affiliation and personal habits and accused him of writing graffiti against Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas. Abu Lihi said that an interrogator tied his hands, made him sit under a desk and threatened him with a gun. Security officials hit him with a wooden stick and a plastic pipe. An interrogator who identified himself as Husam Abu Saif, offered to release Abu Lihi if he would agree to collect intelligence information, but he refused, he said, and was released later that day.

He said that after his release he received multiple phone calls from Abu Saif, and that intelligence officials came to his house. He went into hiding for four days and then surrendered at intelligence headquarters on November 25. Security officers held him there for two days, during which they beat and kicked him in his groin area, despite a pre-existing medical condition there, punched him, and cursed him. They asked him why he writes against the Palestinian president and told him that if he confessed to spray-painting the word, intifada (uprising), they would release him. He signed a confession and was allowed to leave.

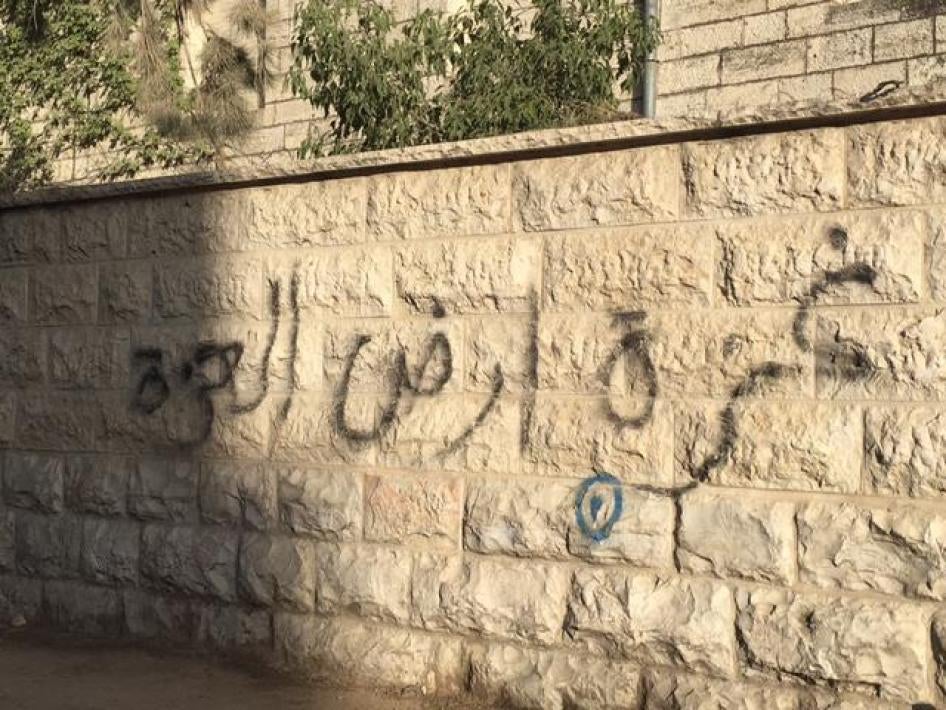

Security forces arrested Abu Lihi a third time on January 12, 2015, and held him for 24 days, taking him, on January 19, before a judge, who approved extending his detention. Abu Lihi said that security officers accused him of writing graffiti, including slogans such as “Abbas Leave,” “Down with Oslo,” a reference to the interim peace accords that created the PA, “Gaza is closer than Paris,” a reference to the separation between the two parts of the Palestinian territory, and pro-Hamas slogans. Abu Lihi said his interrogators told him they would not release him unless he confessed or implicated his friends.

He said that four or five officers made him remove his clothing, then opened the windows to the winter air, and beat him with their hands and a fire extinguisher pipe. They broke his teeth, doused him with cold water and then hot water, and beat him in his groin. They did not give him adequate food and beat him again on February 5, the day they released him.

An additional member of the rap group, Izza al-Deen Abu Rahmeh, whom security forces also arrested on January 12 and held with Abu Lihi for four or five days, corroborated the physical abuse in a separate interview: “On one of the days, they made us take off all of our clothing except boxers [underwear], and they beat us and threw cold water on us. It was freezing cold; it was the end of January. Mutaz got hit in the face and body, and his teeth were broken.”

Abu Lihi’s teeth were visibly broken in an interview in April 2016, and he said he could not afford to have them fixed.

According to court documents reviewed by Human Rights Watch, the Palestinian prosecution charged Abu Lihi and his fellow rappers with creating strife, under Article 150 of the penal code, and criticizing a higher authority, under Article 195. The prosecution said that Abu Lihi and others sprayed outdoor graffiti whose content was “defamatory sentences that include insults … directed personally against the president of the State of Palestine and against the authorities.” Since his release, Abu Lihi said, he has attended multiple court hearings related to the charges, with the next one scheduled for September.

“I have been going to one court hearing after another, but the witnesses never come,” Abu Lihi said. “Every time they hold a court hearing, I have to miss classes and work.” He said that he had missed final exams due to his 2015 detention and had to repeat the semester. He has stopped making music.

“I don’t want to get in trouble like the rest of my friends who sang about freedom,” Abu Lihi said.

Majd Khawaja

Majd Khawaja, 22, had been a member of the rap group Min al-Alef Lal Ya together with Abu Lihi. On November 19, 2014, security forces arrested and held him for three days, he said. They interrogated him at intelligence headquarters and accused him of painting the word, intifada (uprising) on a wall. He said that one of his interrogators kicked him in his left leg, the site of a bullet wound injury from 2013, causing nerve damage and difficulty moving his leg. He was limping at his interview. Human Rights Watch reviewed a medical report that referred to the pre-existing injury. Khawaja said security officials informed his parents of his arrest but did not allow him to see a lawyer.

Khawaja said that following his arrest, an intelligence officer ordered him to return to intelligence headquarters. After hiding out for a few days, he surrendered on January 18, 2015. Interrogators accused him of having weapons and planning to smuggle people into Jordan. Interrogators also asked him about a song about corruption he had recorded, which was written by his friend Wasim. The words include: “Dear President, I wish you could understand these words. A third intifada while you are sleeping and dreaming.” The interrogators told him that singing against the PA is considered to be a criminal offense.

Security officers took him to court to extend his detention, he said. At the court hearing the prosecution produced signed confessions that Khawaja said were forged. They also charged him with insulting a higher authority and creating internal strife, related to alleged graffiti criticizing President Abbas. He was released on February 1, 2015, and is being tried together with Abu Lihi.

Khawaja said he lost his job as a security guard after missing work during his detention and that he has trouble standing because of the leg injury. Since his release, he has received calls from unidentified people warning him to stop releasing songs. He said that someone hacked the group’s YouTube account and deleted its songs. The other members of the group no longer rap out of fear, but he continues to sing and record in his own name.

“We had a song, fasad, (corruption), in 2013, before we got arrested,” Khawaja said. “It was on my personal page. It was deleted while I was in prison. We don’t know who deleted it on YouTube. It did not have bad words or target specific people. It was about corruption by the PA in general.”

Khawaja said he and others are now self-censoring, trying to communicate using hints or code words to avoid further arrests:

“I still rap politics, but I am more conscious about the choice of words, and I sometimes publish things under different names,” he said.

Prosecution as a Form of Harassment in the West Bank

Lawyers, activists, and watchdog groups have expressed concern that the PA is harassing its critics and intimidating them into self-censorship by charging them with crimes based on their peaceful speech and then dragging them through protracted judicial proceedings that require them to hire lawyers, lose wages from lost work, and miss classes and exams.

In 2015, Human Rights Watch documented the arrest and alleged abuse of two students, Ayman Mahariq, a journalism student at Al Quds University in Abu Dis, and Bara al-Qadi, a media student at Birzeit University near Ramallah. According to court documents that Human Rights Watch reviewed, prosecutors charged both men with slandering a public official under Section 191 of the penal code, which carries a maximum of two years in prison. A magistrate court acquitted Mahariq on September 2, 2015, but the prosecution appealed, and the appellate court convicted him and sentenced him to three months in prison. His lawyer, Anas Barghouti, said that the trial was unfair, because security officials called as witnesses did not show up. Al-Qadi, who was charged in September 2014, is still on trial. His lawyer, Muhanad Karaja, said that prosecution witnesses have repeatedly failed to show up, causing at least seven postponements.

“The goal behind this is to punish people,” Karaja said. His client, Al-Qadi “might lose his university placement, going back and forth to court … It proves that the security forces are above the law.” He criticized the court for granting repeated continuances when security officials failed to appear.

A case against the director of Bethlehem Radio 2000, George Kanawati, finally ended in acquittal in 2015. MADA reported that Kanawati’s trial for slander, after he criticized the Health Ministry in Bethlehem, lasted four years and included 27 court hearings, which Kanawati was required to attend.

Response from Palestinian Authorities

Human Rights Watch interviewed by telephone a Hamas spokesman, Ghazi Hamad, and Brigadier-General Mohammad Lafi, an inspector at the Interior Ministry in Gaza. Hamad offered to meet with Human Rights Watch in person to discuss the case, but for several years Israel has refused to allow Human Rights Watch staff to enter Gaza, and Egypt keeps its border with Gaza mostly closed and has refused Human Rights Watch’s request to cross it.

Hamad denied that security officials torture detainees or made anyone sign commitments to refrain from publishing insults or other criticism of government or military officials. He said that they allow the ICRC, the ICHR, and local human rights groups to visit prisons and monitor treatment, and that in light of complaints from such groups, the authorities have imposed stricter regulations on the security forces. He said that the authorities in Gaza do not arrest people based on political activity:

“We arrest people for criminal offenses,” Hamad said. “People have the freedom to believe and support whoever they want. We make the arrests if they try to use force against society.”

Lafi, of the Interior Ministry, said that authorities respect the right to freedom of speech, and that they follow the rule of law in cases in which people insult others or “libelously attack people in order to instigate public strife.” He said that the political split between Fatah and Hamas and the movement restrictions imposed by Israel “create a unique situation where public disorder and political disagreements and strife can have a detrimental impact on the people.”

He also said that security officials are trained in international humanitarian law by the ICRC, and are trained in human rights, and that all security units are inspected by the Interior Ministry.

“We have very strict regulations,” he said. “We refuse any form of verbal or physical violence. As an inspector, I regularly make unannounced visits; we receive complaints and investigate them; and we have human rights organizations visiting the detention centers.”

Lafi said that the ministry receives about two complaints per month about breaches of regulations, usually by the narcotics department, and where serious violations are found, security officers responsible are arrested. He confirmed that when security officers arrest people for speech-related charges, the officers ask the detainees to sign a commitment that they will provide evidence to support their claims and that “they will not defame or insult people without evidence.” He said he would provide Human Rights Watch with a copy of the document but did not provide it.

Hamad and Lafi also addressed the arrests of al-Aloul, Herzallah and al-Haj.

Regarding al-Aloul’s arrest, Hamad said that he writes statements that are disrespectful and untrue, and that security officers had warned him in the past: “He makes unfounded allegations and does not have any proof for the information he posts as facts.” Hamad said that Gaza’s prosecution could have charged him with defamation, but because the authorities are “sensitive to the arrest of journalists,” they detained him only briefly, and “it was solved in a friendly, socially acceptable manner.

Lafi said that security forces held al-Aloul for only three days and denied that they insulted or beat him. He said that al-Aloul is not a “true” journalist but rather a former member of the security forces who refused to continue to work after Hamas took over internal control of Gaza in 2007.

Regarding Herzallah, Lafi said that security forces arrested him under a military prosecution decision to charge him with insulting the government and public employees under Article 144 of the penal code. He said that security forces did not insult or beat him, and that they have strict orders not to insult or beat anyone. Lafi said that after representatives from some of the political parties in Gaza intervened and after Herzallah signed a pledge “not to defame or spread lies during his work and to provide evidence for his claims,” the Interior Ministry agreed to release him

Regarding al-Haj’s questioning, Hamad said that she wrote false statements and could have been arrested and charged with defamation, but that officials instead released her.

Human Rights Watch also met with PA officials in the West Bank, including the Palestinian attorney general, the chief military prosecutor, and the foreign minister. Human Rights Watch provided information about the two rappers arrested in advance of the meetings and again afterward, but none of the officials responded to requests for specific information about the arrests.

Speaking generally, all three officials noted the progress the PA has made, no longer trying civilians in military courts, since 2011, including for speech-related crimes.

Attorney General Ahmed Barrak said that he tries to minimize prosecutions for insulting a higher authority or public official, and that his office closes hundreds of complaints without filling charges. Some of those complaints, Barrak said, come from security officials who accuse others of defaming or insulting them. He said he uses his discretion to prosecute only the most “serious” cases but would not say what his criteria are.

He acknowledged the significance of Palestine’s ratification of the ICCPR but said that as attorney general he remains subject to and is required to enforce existing domestic law and its criminalization of certain kinds of speech, until those legal provisions are repealed. When asked why he does not use his discretion to avoid prosecuting people for insulting officials, he said, “I am forced to apply those laws until they are changed.” He added that limitations on free speech are necessary in any country, “otherwise there will be anarchy.”

Major General Ismail Faraj, the chief military prosecutor, said that his office has been working to modernize the Palestinian security forces and that any violations of the law are the acts of individuals rather than part of a policy. “We are not perfect,” he said, but “any member of the security force who does not obey the law is prosecuted.” Faraj said that his office encourages members of the public to submit complaints in cases of abuse and takes measures to reassure them that they will not be subject to retaliation. When asked, however, about cases like that of the rappers, who said they will not issue a complaint out of fear, he said that in the absence of a complaint his office cannot investigate. He agreed to look into the allegations against security forces presented to him by Human Rights Watch informally, but he did not subsequently provide additional information.

In response to a question about whether security forces monitor social media, the spokesman for the security forces, Major General Adnan Damiri, said they do, to monitor “terrorist” activity.

Foreign Minister Riyad al-Malaki said that Palestine was in a state of transition, after ratifying nearly all the major international human rights treaties within the last two years. He said that the government was working to bring practices into conformity with Palestine’s international commitments: “I am not proud to hear about these rappers and the way they were treated,” he said.

Palestinian and International Law

The Palestinian Basic Law of 2005 protects the right to freedom of expression. The ICCPR, which Palestine ratified in 2014, holds that “everyone shall have the right to freedom of expression ... to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds.”

In 2011, the United Nations Human Rights Committee issued guidance to state parties on their free speech obligations under article 19 that emphasized the high value the treaty places upon uninhibited expression “in circumstances of public debate concerning public figures in the political domain and public institutions.” It said, “State parties should not prohibit criticism of institutions, such as the army or the administration.” It also warned, “The mere fact that forms of expression are considered to be insulting to a public figure is not sufficient to justify the imposition of penalties.” Defamation should in principle be treated as a civil, not a criminal, issue and never punished with a prison term, the Human Rights Committee said.

As the repeal of criminal defamation laws in an increasing number of countries shows, Human Rights Watch said, such laws are not necessary to protect reputations, and civil remedies, which already exist in Palestinian law, should be adequate.

Yet the Palestinian penal code includes a provision, dating back to when the Ottoman Empire ruled Palestine, that criminalizes insulting a “higher authority” or government. The Palestinian Press and Publications Law (1995) prohibits publishing material that contradicts the principles of freedom, national responsibility, human rights, respect of truth, or national unity. In December 2015, President Abbas passed, by presidential decree, the Higher Media Council Law, to increase executive control over journalists. Publication of the law, which would bring it into force, was suspended in light of strong opposition.

These prohibitions are so vague that they could chill freedom of the press, allow for arbitrary interpretations that violate rights, and violate accused people’s right to defend themselves, as it is impossible to know what types of information, if published, would constitute a crime, Human Rights Watch said.

Human Rights Watch said that to further the goal of bringing their practices into conformity with its international law obligations, the Palestinian penal code should be revised to remove provisions that criminalize defamation, including article 144 on insulting a public official; article 189 on libel in print; article 191 on slandering a public official; and article 195 on insulting a higher authority. Palestine should also rescind Article 150 of its penal code, a vaguely worded provision criminalizing creating “sectarian strife,” which can be easily used to punish dissent.

The Palestinian legislature has not had a quorum since 2007, when the Hamas and Fatah factions broke with each other. Until the penal code can be revised, prosecutors and security officials should refrain from enforcing these laws, which are inconsistent with Palestinian basic laws protecting free speech and the international conventions that Palestine ratified in 2014. Security officials should stop arresting, detaining and charging people for their writing; as long as it does not cross the line to incitement to violence. Judges should interpret the law in light of the international standards for protecting speech that Palestine has adopted.

While government officials and those involved in public affairs are entitled to protection of their reputation, including protection against defamation, as individuals who have sought to play a role in public affairs they should tolerate a greater degree of scrutiny and criticism than ordinary citizens. This distinction serves the public interest by making it harder for those in positions of power to use the law to deter or penalize those who seek to expose official wrongdoing, and it facilitates public debate about issues of governance and common concern. Public officials should avoid suing for defamation, but rather should respond to criticism they feel is unfair through the many avenues of public discussion open to them.

In addition, West Bank security officials should refrain from interrogating people at the headquarters of the intelligence services and instead conduct any necessary questioning at interrogation facilities equipped with cameras. In Gaza, to deter abuse, authorities should install cameras at facilities where interrogations take place. Authorities in both places should investigate persistent allegations of abuse by security officials, regardless of whether complaints are filed, and punish those responsible.