In 2012, political cartoonist Aseem Trivedi was charged with sedition for uploading some of his sketches that were critical of the government. “I found a lawyer who fought my case for free,” he said, adding that fighting a criminal case can prove too expensive for an artist.

Trivedi was arrested and spent four days in custody before being granted bail. “It’s not just about how many days you spend in jail or the financial costs you have to bear,” he said. “Your voice of dissent is crushed and your work suffers. All your energy goes into fighting the case. And socially, you are branded an anti-national.”

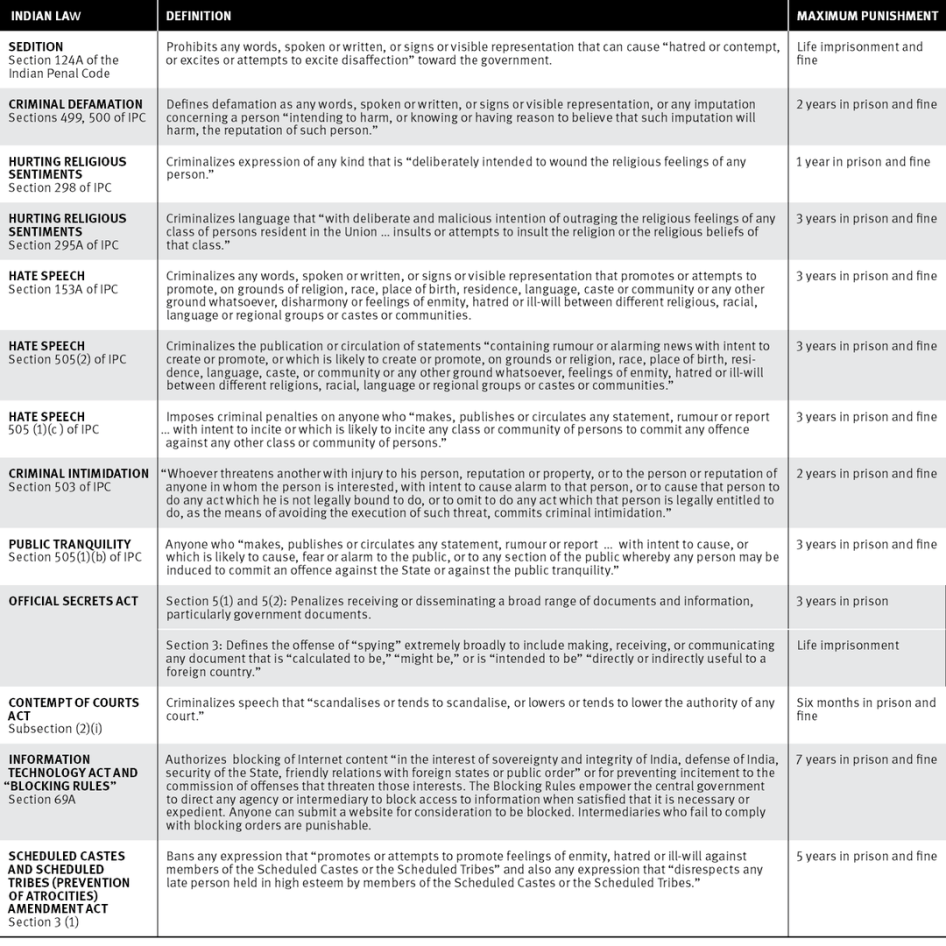

India has a long list of overbroad and vague laws restricting free speech that have proved susceptible to abuse, as documented in a new report by Human Rights Watch. These laws include sedition, criminal defamation, hate speech, hurting religious sentiments, contempt of court, the Official Secrets Act, and the Information Technology Act.

The country’s authorities routinely use these laws to punish and silence critics, resulting in a chilling effect on dissent. Journalists, activists and artists remain especially vulnerable, as they attempt to speak truth to power.

Awaiting bail

Many of these laws constitute cognisable offences, meaning the police can arrest the accused without a warrant. The majority are also non-bailable, thus leaving the question of bail to the discretion of the court.

Lower courts are generally reluctant to grant bail when it comes to laws dealing with national security or issues such as sedition, the Official Secrets Act, or the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act. The accused often remain in custody until they can appeal in the higher courts.

For instance, six members of the cultural group Kabir Kala Manch in Maharashtra were arrested under Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act for allegedly being members of the banned Communist Party of India (Maoist) between 2011 and 2013. Three remain in jail, having failed to secure bail.

In 2002, journalist Iftikhar Gilani spent seven months in jail under the Official Secrets Act. He said it took four months for him to even get a bail hearing, and then his application was rejected.

Gilani was accused of possessing a supposedly classified document which detailed, among other things, the deployment of Indian troops in Jammu and Kashmir. The document in question was published by the Institute of Strategic Studies, a think tank in Pakistan, and was available both online and in libraries in New Delhi.

He was released only after the government withdrew the case in January 2003, following a statement by intelligence officials that the document in connection with which Gilani was arrested was “readily available” and of “negligible security value.”

Dragging on

Gilani's case, like many others, shows how absurd the charges can be. Laws can be misused for transparently political purposes. In March 2014, Uttar Pradesh authorities slapped sedition charges on more than 60 Kashmiri students who cheered for Pakistan during an India-Pakistan cricket match. The same year in August, police in Kerala filed a sedition case against seven youths, including students, who refused to stand up while the national anthem was being played at a cinema hall.

Given the absurd nature of the cases, some are ultimately dismissed or abandoned. But cases often can drag on for long periods, and the prosecution often deliberately delays hearings. Scores of criminal defamation cases filed by the State of Tamil Nadu have been continuing for years and require the accused, many of whom are journalists and editors, to appear in court every couple of weeks. At most hearings, the case is simply adjourned and a date for a new hearing is set. This costs both time and money.

“The intention of the government is only to create a fear psychosis among journalists and newspapers,” said P Thirumavelan, the editor of Junior Vikatan magazine, who has several cases pending against him. “If the government was really serious, they would counter with evidence in a court of law.”

In other cases, police don’t file charges for years. Nearly 9,000 people, most of them villagers from fishing communities, were accused of sedition in 2012 for protesting against the building of the Kudankulam civil nuclear power plant in Tamil Nadu. Almost four years later, the accused and their lawyers are still in the dark about the status of the case.

Two years after the students in Kerala were charged with sedition for not standing up for the national anthem, the police have still not filed charges. Salmaan Mohammed, one of the accused, spent over a month in jail and had his bail application rejected twice. Even after he received bail, the conditions required him to visit the local police station twice a week for six months. He also had to sign an affidavit saying he wouldn’t apply for a passport until the sedition charges against him were resolved.

Another serious concern is of excessive charges being applied. Many laws are used in conjunction with each other to intimidate the accused. When Trivedi was charged with sedition for his cartoons, he was also slapped with section 66A of the Information Technology Act as he had posted those cartoons online, and with charges under the Insults to National Honour Act, 1971. The sedition cases were dropped within a month, while charges under 66A – another abused law posing unreasonable restrictions on free speech – were dropped after the law was struck down by the Supreme Court in 2015. But nearly four years later, charges under the provisions of the Insults to National Honour Act remain pending against Trivedi.

When filing sedition cases, police routinely ignore or defy Supreme Court guidelines, limiting the scope of sedition law to require evidence of incitement to violence. Cases frequently have to climb up the court system before they are dismissed.

What can be done

The government needs to prioritise training for the police to ensure they do not file inappropriate and irrelevant cases. Too often, the police seem unaware that India is a democracy in which peaceful criticism is allowed, and is not a crime. Judges, particularly in the lower courts, should be better trained about peaceful expression standards so that they dismiss cases that infringe on protected speech.

Earlier this month, a two-member bench of the Supreme Court issued a disappointing verdict upholding the constitutionality of criminal defamation law, a colonial-era relic, despite India’s international law obligations. This decision makes India an outlier among democracies, which have long allowed only civil remedies for defamation, and it will allow the authorities to continue to arrest and imprison people for peacefully expressing their views.

Indian citizens should no longer have to worry about being “punished by the process” of being subjected to bad laws and the whims of poorly trained police.

The government should set up an independent commission to review all laws that criminalise speech and take steps to repeal or amend them to bring them in line with international human rights norms and India’s treaty obligations. So long as bad laws remain on the books, they will serve as tools for governments or local power-holders to harass critics and clamp down on free speech.