Summary

When it comes to democracy, liberty of thought and expression is a cardinal value that is of paramount significance under our constitutional scheme.

—Supreme Court of India, Shreya Singhal v. Union of India, March 24, 2015.

Freedom of expression is protected under the Indian constitution and international treaties to which India is a party. Politicians, pundits, activists, and the general public engage in vigorous debate through newspapers, television, and the Internet, including social media. Successive governments have made commitments to protect freedom of expression.

“Our democracy will not sustain if we can’t guarantee freedom of speech and expression,” Prime Minister Narendra Modi said in June 2014, after a month in office. Indeed, free speech is so ingrained that Amartya Sen’s 2005 book, The Argumentative Indian, remains as relevant today as ever.

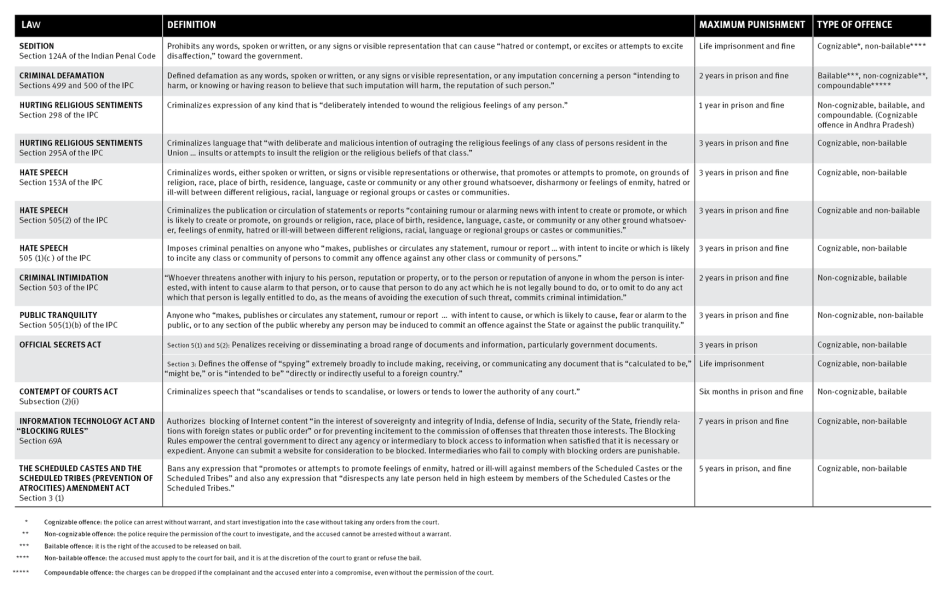

Yet Indian governments at both the national and state level do not always share these values, passing laws and taking harsh actions to criminalize peaceful expression. The government uses draconian laws such as the sedition provisions of the penal code, the criminal defamation law, and laws dealing with hate speech to silence dissent. These laws are vaguely worded, overly broad, and prone to misuse, and have been repeatedly used for political purposes against critics at the national and state level.

While some prosecutions, in the end, have been dismissed or abandoned, many people who have engaged in nothing more than peaceful speech have been arrested, held in pre-trial detention, and subjected to expensive criminal trials. Fear of such actions, combined with uncertainty as to how the statutes will be applied, leads others to engage in self-censorship.

In many cases, successive Indian governments have failed to prevent local officials and private actors from abusing laws criminalizing expression to harass individuals expressing minority views, or to protect such speakers against violent attacks by extremist groups. Too often, it has instead given in to interest groups who, for politically motivated reasons, say they are offended by a certain book, film, or work of art. The authorities then justify restrictions on expression as necessary to protect public order, citing risks of violent protests and communal violence. While there are circumstances in which speech can cross the line into inciting violence and should result in legal action, too often the authorities, particularly at the state level, misuse or allow the misuse of criminal laws as a way to silence critical or minority voices.

This report details how the criminal law is used to limit peaceful expression in India. It documents examples of the ways in which vague or overbroad laws are used to stifle political dissent, harass journalists, restrict activities by nongovernmental organizations, arbitrarily block Internet sites or take down content, and target religious minorities and marginalized communities, such as Dalits.

The report identifies laws that should be repealed or amended to bring them into line with international law and India’s treaty commitments. These laws have been misused, in many cases in defiance of Supreme Court rulings or advisories clarifying their scope. For example, in 1962, the Supreme Court ruled that speech or action constitutes sedition only if it incites or tends to incite disorder or violence. Yet various state governments continue to charge people with sedition even when that standard is not met.

While India’s courts have generally protected freedom of expression, their record is uneven. Some lower courts continue to issue poorly reasoned, speech-limiting decisions, and the Supreme Court, while often a forceful defender of freedom of expression, has at times been inconsistent, leaving lower courts to choose which precedent to emphasize. This lack of consistency has contributed to an inconsistent terrain of free speech rights and left the door open to continued use of the law by local officials and interest groups to harass and intimidate unpopular and dissenting opinions.

The problem in India is not that the constitution does not guarantee free speech, but that it is easy to silence free speech because of a combination of overbroad laws, an inefficient criminal justice system, and the aforementioned lack of jurisprudential consistency. India’s legal system is infamous for being clogged and overwhelmed, leading to long and expensive delays that can discourage even the innocent from fighting for their right to free speech.

The Sedition Law

The sedition law, section 124A of the Indian Penal Code (IPC), is a colonial-era law that was once used against political leaders seeking independence from British rule. Unfortunately, it is still often used against dissenters, human rights activists, and those critical of the government.

The law allows a maximum punishment of life in prison. It prohibits any signs, visible representations, or words, spoken or written, that can cause “hatred or contempt, or excite or attempt to excite disaffection” toward the government. This language is vague and overbroad and violates India’s obligations under international law, which prohibit restrictions on freedom of expression on national security grounds unless they are strictly construed, and necessary and proportionate to address a legitimate threat. India’s Supreme Court has imposed limits on the use of the sedition law, making incitement to violence a necessary element, but police continue to file sedition charges even in cases where this requirement is not met.

Convictions for sedition are rare, but this apparently has not deterred the authorities from booking and arresting people for it. According to the government’s National Crime Records Bureau, which started collecting specific information on sedition in 2014, that same year 47 cases were registered across the country, 58 people were arrested, and one person was convicted. The official 2015 data is not yet available, but, media watchdog website The Hoot reported a significant increase in arrests in the first quarter of 2016. 11 cases were booked against 19 people, in the first three months of 2016, compared to none during the same period in the previous two years.

In February 2016, police in Delhi arrested Kanhaiya Kumar, a student union leader at the Jawaharlal Nehru University, after members of the student wing of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) accused him of making anti-national speeches during a meeting organized on campus. The public meeting was held on February 9 to protest the 2013 hanging of MohammadAfzal Guru, who was convicted for his role in a December 2001 attack on parliament that killed nine people. Afzal Guru’s execution remains a matter of intense debate in the country. The Delhi police admitted to the court that Kumar had “not been seen” raising any anti-national slogans in the video footage available. The Delhi High Court granted him bail in March. Five more students were booked in the case; two, Umar Khalid and Anirban Bhattacharya, were also arrested and later released on bail.

However, despite the police’s admission that they had no evidence of anti-national sloganeering by Kumar, and certainly no evidence of incitement to violence, the government has yet to admit that the arrests were wrong. Kumar’s arrest thus reveals how divided the country remains over the meaning of tolerance and the imperative of legal protection of peaceful, if disfavored, expression.

There are many other prominent examples of use of the sedition provision to silence political speech. In May 2012, for example, police in Tamil Nadu filed sedition complaints against thousands of people who had peacefully protested the construction of a nuclear power plant in Kudankulam. According to S.P. Udaykumar, founder of the People’s Movement Against Nuclear Energy, which led the struggle against the project, 8,956 people face allegations of sedition in 21 cases. A public hearing organized by activists belonging to the Chennai Solidarity Group in May 2012, which included a former chief justice of the Madras and Delhi High Courts, found that the state had denied the protesters both freedom of speech and freedom of assembly.

A report by a different fact-finding team in September 2012 alleged that state authorities had used “unjustified” force against peaceful protesters to silence dissent. As that report concluded:

If people who have resisted and protested peacefully for a year can be charged with sedition and waging war against the nation in such a cavalier way as has been done here, what is the future of free speech and protest in India?

In September 2012, the authorities in Mumbai arrested political cartoonist Aseem Trivedi on sedition charges after a complaint that his cartoons mocked the Indian constitution and national emblem. The charges were dropped a month later following public protests and furor on social media.

In March 2014, authorities in Uttar Pradesh charged over 60 Kashmiri students with sedition for cheering for Pakistan in a cricket match against India. The Uttar Pradesh government dropped the charges only after seeking a legal opinion from the law ministry. In August 2014, the authorities in Kerala charged seven youth, including students, with sedition, acting on a complaint that they refused to stand up during the national anthem inside a movie theater.

In October 2015, authorities in Tamil Nadu state arrested folk singer S. Kovan under the sedition law for two songs that criticized the state government for allegedly profiting from state-run liquor shops at the expense of the poor.

Criminal Defamation

Human Rights Watch believes that criminal defamation laws should be abolished, as criminal penalties infringe on peaceful expression and are always disproportionate punishments for reputational harm. Criminal defamation laws are open to easy abuse, resulting in very harsh consequences, including imprisonment. As the repeal of criminal defamation laws in an increasing number of countries shows, such laws are not necessary for the purpose of protecting reputations.

The frequent use of criminal defamation charges by the Tamil Nadu state government, led by Chief Minister Jayalalithaa, against journalists, media outlets, and rival politicians is illustrative of how the law can be used to criminalize critics of the government. The Tamil Nadu government reportedly filed nearly 200 cases of criminal defamation between 2011 and 2016. The Tamil-language magazines Ananda Vikatan and Junior Vikatan, both published by the Vikatan group, face charges in 34 criminal defamation cases, including for a series of articles assessing the performance of each cabinet minister.

In November 2015, while staying a criminal defamation case by the Tamil Nadu state government against a politician from an opposition party, the Supreme Court questioned the large number of such cases coming from the state. The judges said:

These criticisms are with reference to the conceptual governance of the state and not individualistic. Why should the state file a case for individuals? Defamation case is not meant for this.

In recent years corporations and businesses have also used criminal defamation laws to suppress critical speech and harass journalists and writers. The Indian Institute of Planning and Management, a business school with its headquarters in New Delhi, filed several criminal (and civil) defamation lawsuits to prevent the publication of content critical of the institute. For example, in2009, IIPM filed a criminal defamation complaint against Maheshwer Peri, publisher of the Outlook and Careers360magazines, for an article on private educational institutions that were allegedly deceiving students. The article mentioned IIPM and was the first in a series of investigative articles questioning the authenticity of claims made by IIPM. The suits were often filed in remote parts of the country such as Silchar, Assam, where neither IIPM nor the defendant were based nor had any presence.

By January 2016, after the courts quashed a couple of criminal defamation cases against Peri, IIPM had withdrawn all legal cases against him. Peri told Human Rights Watch: “Criminal defamation is used to threaten and bully rather than to seek justice, and should be done away with.”

In May 2016, a two-justice bench of the Supreme Court, upheld the constitutionality of India’s criminal defamation law, saying: “A person's right to freedom of speech has to be balanced with the other person's right to reputation.” The court did not explain how it concluded that the law does not violate international human rights norms, which do not allow imprisonment for criminal defamation, or offer a clear or compelling rationale why civil remedies are insufficient for defamation in a democracy with a functioning legal system.

Laws Regulating the Internet

Indian authorities appear to be unnerved by the explosion of the Internet, and have stumbled in their efforts to regulate it.

Laws to regulate social media, such as India’s Information Technology Act, can and do easily become tools to criminalize speech, often to protect powerful political figures. Section 66A of that act, which criminalizes a broad range of speech, has been repeatedly used to arrest those who criticize the authorities and to censor content.

For example, in May 2014, five students were temporarily detained in Bangalore for allegedly sharing a message on the mobile application “WhatsApp” that was critical of newly elected Prime Minister Narendra Modi. In April 2012, Ambikesh Mahapatra, a professor of chemistry at Jadavpur University in the eastern state of West Bengal, was arrested under section 66A for forwarding an email featuring a spoof of the state’s chief minister, Mamata Bannerjee. A month later, police in Puducherry arrested a businessman for posting messages on Twitter questioning the wealth amassed by the son of the country’s then-finance minister.

Section 66A was declared unconstitutional by the Indian Supreme Court in March 2015. The government has said that it is examining the Supreme Court judgment and may enact an amended version of section 66A to bring it into line with constitutional requirements. The Supreme Court judgment lays down important safeguards for the future of Internet freedom in India. While aspects of the judgment relating to the blocking of Internet content raise concerns (detailed later in this report), any new laws should be consistent with the safeguards set forth in the court’s ruling and with international human rights standards.

Counterterrorism Laws

Counterterrorism laws such as the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) have also been used to criminalize peaceful expression. In India, counterterrorism laws have been used disproportionately against religious minorities and marginalized groups such as Dalits. Between 2011 and 2013, the authorities in Maharashtra arrested six members of Kabir Kala Manch, a cultural group, under counterterrorism laws, claiming that they were secretly members of the Communist Party of India (Maoist), a banned organization. The authorities produced no evidence of such membership, however, and the members dismiss the claim as entirely unfounded. The Pune-based group of singers, poets, and artists consists largely of Dalit youth and uses music, poetry, and street plays to raise awareness about issues such as oppression of Dalits and tribal groups, social inequality, corruption, and Hindu-Muslim relations.

Those charged with violating the counterterrorism laws are considered “anti-national,” so simply being charged can have a severe impact on the lives of the accused and their families, even if they are ultimately judged innocent. Mumbai-based lawyer Vijay Hiremath, who has worked on counterterrorism-related cases, told Human Rights Watch:

They will be under surveillance and police will keep a watch on them. It will be difficult for them to lead normal lives even after acquittal because whatever they do will be looked at with a lot of suspicion.

The Process is the Punishment

Going through the legal process in India can often be a punishment in itself. Defendants in the country’s criminal justice system often face lengthy, drawn-out proceedings. In some cases, judges also appear to be poorly trained in issues of freedom of expression and fail to heed Supreme Court guidance when it comes to imposing limits on peaceful expression.

While the higher courts, and particularly the Supreme Court, often end up dismissing cases brought under laws criminalizing peaceful expression, the dismissals are often too late to protect those arrested or charged from serious consequences. Some offenses under these laws can be non-bailable and the accused may be taken into pre-trial custody. Laws dealing with sedition, terrorism, and national security extract a heavy price from the accused during the trial process. Legal proceedings can take a heavy toll on the financial resources of the accused.

For instance, the Official Secrets Act, a law that criminalizes the disclosure, possession, or receipt of a wide range of documents or information without requiring proof that such acts threaten national security or public order, fosters a culture of secrecy that runs counter to the public’s interest in access to information about government activity. Journalists covering defense or intelligence matters are particularly at risk of being charged under the law. The penalty for “spying” under the law allows for imprisonment of up to 14 years. While some of the cases filed under the Official Secrets Act are ultimately dismissed by the higher courts, the dismissal does not obviate the harm suffered by those charged.

While the Official Secrets Act is not as frequently used as some other laws discussed in this report, such as sedition or criminal defamation, it has a serious chilling effect. The accused can end up spending months, or even years, in jail without being granted bail. One of the most prominent cases of misuse of this law is that of journalist Iftikhar Gilani. His 2002 arrest also illustrates the toll the process takes on the accused. Gilani was accused of possessing a classified document even though the document was available both on the Internet and in public libraries in Delhi. He was acquitted in January 2003, but spent seven months in jail without bail while the case was pending. Gilani said it took four months for him to even get a hearing for bail, and then his application was rejected. Those accused under the OSA are considered serious enemies of the state, which makes obtaining bail extremely difficult.

“By the time you prove that the material you have is not a secret, you may have been in jail for many years. That’s the kind of bias judges have when someone is charged with OSA,” said Trideep Pais, a lawyer who has dealt with Official Secrets Act cases in Delhi.

Other laws which criminalize peaceful expression can be quite punishing, too. For instance, criminal defamation cases filed by Tamil Nadu state have been dragging on for years and require the accused, many of whom are journalists and editors, to appear in court every couple of weeks. At most hearings, the case is simply adjourned and the date for a new hearing is set. This costs both time and money, as the editor of Junior Vikatan magazine, P. Thirumavelan, who faces several cases himself, said.

The government is not interested in pursuing a case. The intention of the government is only to create a fear psychosis among journalists and newspapers. Because if the government were really serious, they would counter with evidence in a court of law.

According to media lawyer Gautam Bhatia, criminal cases restrict speech to a far greater extent than civil cases, by placing onerous burdens upon the accused. In an article on the news website Scroll.in, Bhatia wrote:

The threat of arrest at any moment, and the possibility of eventual imprisonment exercise a deep and pervasive chilling effect upon would-be speakers; the requirement that the accused must be present at the place of hearing, coupled with the fact that there is no limit to the number of cases that can be filed, is an open invitation to harassment. And even if the accused has a good defence, he is only allowed to bring up his defence after the trial commences. Consequently, in even the most frivolous of cases, the accused must face the legal process throughout the long pre-trial stage, which itself has the potential to drag on for months, if not years.

As a result, those faced with even unfounded criminal charges often withdraw the “offending” words rather than endure the often prolonged legal, financial, and personal impact of those charges. On the other hand, there is little consequence for the complainant if the case is found to be frivolous.

The Heckler’s Veto

Several Indian laws prohibit “hate speech,” such as speech that causes enmity between different groups of people, or speech that insults religion. While the goal of preventing inter-communal strife is an important one in a country as diverse as India, that goal should be pursued through prompt and vigorous prosecution of perpetrators of violent acts and incitement to violence, not through broadly worded laws limiting expression.

India’s hate speech laws are so broad in scope that they infringe on peaceful speech and fail to meet international standards. Intended to protect minorities and the powerless, these laws are often used at the behest of powerful individuals or groups, who claim that they have been offended, to silence speech they do not like. The state too often pursues such complaints, thereby leaving members of minority groups, writers, artists, and scholars facing threats of violence and legal action.

The example of Maqbool Fida Husain, among India’s best-known artists, is an emblematic case of public intolerance. Husain was forced into exile after Hindu right-wing groups targeted him, accusing him of painting nude pictures of Hindu gods and goddesses, and thus offending their sentiments. Hardline Hindu groups attacked Husain’s house and art galleries which exhibited his works, but the governments in Gujarat, Maharashtra, and Delhi states failed to protect him or his work. Instead, Bal Thackeray, a senior leader from the ruling Shiv Sena party in Maharashtra state, endorsed the attack on Husain’s home in Mumbai in 1998, saying, “If Husain can enter Hindustan [India]…why can't we enter his house?” Private individuals filed cases against him in different cities across the country under criminal hate speech and obscenity laws, forcing him to travel around the country to answer the complaints.

The Delhi High Court in 2008 upheld Husain’s right to free speech and dismissed charges of obscenity and of hurting religious feelings against him in a case related to the “Bharat Mata” painting. The court said:

There should be freedom for the thought we hate…It must be realised that intolerance has a chilling, inhibiting effect on freedom of thought and discussion. The consequence is that dissent dries up. And when that happens democracy loses its essence.

Despite a ruling by the Indian Supreme Court that freedom of expression cannot be suppressed on account of threats of violence because “that would be tantamount to negation of the rule of law and a surrender to black mail and intimidation,” the police routinely arrest individuals based on the reactions to their speech. For instance, in November 2012, Shaheen Dhada and Rinu Srinivasan, both 21 years old, were arrested in Maharashtra for a Facebook post questioning the shutdown of Mumbai following the death of a powerful political leader. The police acted after the politician’s supporters complained and mobs engaged in violent attacks.

Similarly, Shirin Dalvi, editor of an Urdu newspaper in Mumbai, was charged by police with “outraging religious feelings” with “malicious intent” in January 2015 after numerous First Information Reports (FIRs, or criminal complaints) were filed by individuals and Muslim groups offended by her reprinting of a cartoon originally published by the controversial French magazine Charlie Hebdo. Dalvi said she had to go into hiding and temporarily move away from her house after her release on bail to escape the constant harassment and threats on the phone. The cases against her are pending at time of writing.

In January 2015, local caste groups in Namakkal village in Tamil Nadu protested against a book by resident Tamil author Perumal Murugan. They burned copies of his book, shut down shops, and asked the police to take action against him. Police and district administration officials, instead of protecting Murugan from angry mobs, asked him to tender an unconditional apology. As a result of the harassment, Murugan decided to give up his writing career and withdraw all his works from publication.

International Law

In 1979, India ratified the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which sets forth internationally recognized standards for the protection of freedom of expression. Yet, as detailed here, a series of Indian legal provisions, some of them used by prosecutors and litigants on a regular basis, continue to restrict speech in ways inconsistent with that covenant. In some cases, the Indian Supreme Court has properly issued rulings narrowing the scope of the laws, but they continued to be misused, making clear that the laws themselves need to be amended or repealed if India is to comply with its international obligations.

Importantly, the consequences of violations go beyond improper limits on speech. As former UN Special Rapporteur on freedom of expression Frank La Rue has stated, freedom of expression is not only a fundamental right but also an “enabler” of other rights, “including economic, social and cultural rights, such as the right to education and the right to take part in cultural life and to enjoy the benefits of scientific progress and its applications, as well as civil and political rights, such as the rights to freedom of association and assembly…. [A]rbitrary use of criminal law to sanction legitimate expression constitutes one of the gravest forms of restriction to the right, as it not only creates a ‘chilling effect,’ but also leads to other human rights violations.”

Key Recommendations

Indian laws and practices that criminalize peaceful expression are inconsistent with its international legal obligations, undermine rather than strengthen efforts to combat communal violence, and, because freedom of expression is an enabler of other rights, threaten to erode human rights protections more generally.

Human Rights Watch recommends that India:

- Develop a clear plan and timetable for the repeal or amendment of laws that criminalize peaceful expression as detailed at the end of this report and, where legislation is to be amended, consult thoroughly with civil society groups in a transparent and public way.

- Drop all prosecutions and close all investigations into cases where the underlying behavior involved peaceful expression or assembly.

- Train the police to ensure inappropriate cases are not filed with courts. Train judges, particularly in the lower courts, on peaceful expression standards so that they dismiss cases that infringe on protected speech.

Methodology

This report was researched and written between May 2014 and January 2016. It is based on interviews with lawyers, victims of laws criminalizing free speech including journalists and rights activists, members of civil society organizations, and academics and experts on free speech. The report draws from existing literature on laws criminalizing expression in India and news reports of criminal proceedings in cases related to free speech. We also reviewed international and Indian case law and jurisprudence.

An international lawyer provided a comparative analysis of relevant Indian and international laws and of the compliance of Indian laws with international human rights standards. Two Indian lawyers also provided analysis of the Indian laws and of how Indian courts have interpreted constitutional guarantees for freedom of expression.

The report is not meant to be a comprehensive list of all laws that criminalize free speech in India. It analyzes laws that have been most prone to misuse and abuse, some of which carry a punishment of as much as life imprisonment.

On April 4, 2016, we wrote letters to the Indian government and to the Tamil Nadu state government seeking data and further information on some of the laws and cases addressed in this report. On the same day, we also wrote a letter to Bloomsbury Publishing India Private Limited seeking their view on a criminal defamation case involving the company addressed in this report. We had not received replies at the time of writing.

I. International and Domestic Legal Standards

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (“ICCPR”),[1] which India ratified in 1979, provides that:

- Everyone shall have the right to hold opinions without interference.

- Everyone shall have the right to freedom of expression; this right shall include freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through any other media of his choice.

- The exercise of the rights provided for in paragraph (2) of this article carries with it special duties and responsibilities. It may therefore be subject to certain restrictions, but these shall only be such as are provided by law and are necessary: For respect of the rights or reputations of others; (b) For the protection of national security or of public order (ordre public), or of public health or morals.

The ICCPR is an outgrowth of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (“UDHR”), adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1948,[2] which provides in article 19 that:

Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.[3]

The UN Human Rights Committee (HRC), the treaty body of independent experts that provides an authoritative interpretation of the ICCPR, has stressed the importance of freedom of expression in a democracy:

[T]he free communication of information and ideas about public and political issues between citizens, candidates and elected representatives is essential. This implies a free press and other media able to comment on public issues without censorship or restraint and to inform public opinion.... [C]itizens, in particular through media, should have wide access to information and the opportunity to disseminate information and opinions about the activities of elected bodies and their members.[4]

The guarantee of freedom of expression applies to all forms of expression, not only those that fit with majority viewpoints and perspectives, as noted by the European Court of Human Rights in the seminal Handyside case:

Freedom of expression constitutes one of the essential foundations of [a democratic] society, one of the basic conditions for its progress and for the development of every man... [I]t is applicable not only to ‘information’ or ‘ideas’ that are favourably received or regarded as inoffensive or as a matter of indifference, but also to those that offend, shock or disturb the State or any sector of the population. Such are the demands of pluralism, tolerance and broadmindedness without which there is no ‘democratic society.’[5]

Under international law, the right to freedom of expression is not absolute. Given its paramount importance in any democratic society, however, the UN Human Rights Committee has held that any restriction on the exercise of this right must meet a strict three-part test. Such a restriction must: (1) be “provided by law”; (2) be imposed for the purpose of safeguarding respect for the rights or reputations of others, or the protection of national security or of public order (ordre public), or of public health or morals; and (3) be necessary to achieve that goal.[6]

To be “provided by law,” a norm must be formulated with sufficient precision to enable an individual to regulate his or her conduct accordingly.[7]

He must be able – if need be with appropriate advice – to foresee, to a degree that is reasonable in the circumstances, the consequences that a given action may entail.[8]

Measures that seek to protect a legitimate interest must be “necessary” to achieve that purpose. This is a strict test:

[The adjective ‘necessary’] is not synonymous with “indispensable,” neither has it the flexibility of such expressions as “admissible,” “ordinary,” “useful,” “reasonable,” or “desirable”. [It] implies the existence of a “pressing social need.”[9]

Finally, any restrictions must be proportional to the aim they are designed to achieve, and restrict freedom of expression as little as possible.[10] As articulated by the UN Human Rights Committee:

[R]estrictive measures must conform to the principle of proportionality; they must be appropriate to achieve their protective function; they must be the least intrusive instrument amongst those which might achieve their protective function; they must be proportionate to the interest to be protected.[11]

Broadly defined provisions, while they may meet the requirement of being “provided by law,” are thus unacceptable if they go beyond what is required to protect a legitimate interest.

While generally protecting the right to freedom of expression, the ICCPR requires signatories to prohibit certain types of expression in article 20:

- Any propaganda for war shall be prohibited by law.

- Any advocacy of national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence shall be prohibited by law.

According to principle 12 of the Camden Principles on Freedom of Expression and Equality (“Camden Principles”),[12] prepared in 2009 and repeatedly cited with approval by the Special Rapporteur on freedom of expression Frank La Rue:

- The terms “hatred” and “hostility” refer to intense and irrational emotions of opprobrium, enmity and detestation towards the target group.

- The term “advocacy” is to be understood as requiring an intention to promote hatred publicly towards the target group.

- The term “incitement” refers to statements about national, racial or religious groups which create an imminent risk of discrimination, hostility or violence against persons belonging to those groups.

Any restriction of expression based on article 20 must also comply with the limitations of article 19(3).[13]

When analyzed pursuant to these standards, a number of the laws currently in effect in India impose limitations on expression that go beyond the restrictions that are permitted by international law and, in some cases, appear to conflict with the Indian constitution. While, with respect to some of those laws, the Indian Supreme Court has issued opinions narrowing the scope of laws that are facially in conflict with international standards, the continued application of those laws in ways that are inconsistent with international standards of freedom of expression makes clear that the laws themselves need to be amended or repealed.

As much as the right to freedom of expression is a fundamental right, it is also an “enabler” of other rights, “including economic, social and cultural rights, such as the right to education and the right to take part in cultural life and to enjoy the benefits of scientific progress and its applications, as well as civil and political rights, such as the rights to freedom of association and assembly.”[14] Special Rapporteur on freedom of expression La Rue, therefore, stated that “arbitrary use of criminal law to sanction legitimate expression constitutes one of the gravest forms of restriction to the right, as it not only creates a “chilling effect,” but also leads to other human rights violations.”[15]

The Indian Constitution

The Indian constitution expressly protects freedom of expression in article 19(1)(a), which provides that “all citizens shall have the right to freedom of speech and expression.”[16] The Indian Supreme Court has held that freedom of expression under article 19(1)(a) includes the right to seek and receive information, including information held by public bodies.[17]

The constitutional right to freedom of expression is limited, however, by article 19(2), which permits “reasonable restrictions… in the interests of the sovereignty and integrity of India, the security of the State, friendly relations with foreign States, public order, decency or morality or in relation to contempt of court, defamation or incitement to an offense.”

In this sense, the Indian constitution is less protective of peaceful expression than the ICCPR, which permits only restrictions that are “necessary” “for respect of the rights or reputation of others, for protection of national security or of public order (ordre public) or of public health or morals.”[18]

The Indian Supreme Court has made clear, however, that only restrictions in the interest of one of the eight specified interests can pass constitutional muster:[19] in March 2015, in striking down section 66A of the Information Technology Act, the court ruled that “any law seeking to impose a restriction on the freedom of speech can only pass muster if it is proximately related to any of the eight subject matters set out in Article 19(2).”[20]

Interpreting the Constitution

In interpreting section 19(2), the Supreme Court has generally been protective of the right to freedom of speech. For instance, in 1988, in Ramesh v. Union of India, a case concerning whether the television show Tamas should be pulled because it could incite violence and disrupt public order, the Supreme Court held that:

The effect of the words must be judged from the standards of reasonable, strong-minded, firm and courageous men, and not those of weak and vacillating minds, nor of those who scent danger in every hostile point of view.[21]

The Supreme Court has also ruled that advocacy of unpopular causes is protected by the constitution as long as it does not rise to the level of incitement,[22] as is criticism of government action.[23]

The scope and extent of protection of free speech in India is largely determined by the interpretation of the terms “reasonable restrictions” and “in the interests of,” and of the various grounds listed in article 19(2). The Supreme Court jurisprudence on some of these issues has, however, been inconsistent.

For example, the court has interpreted the phrase “in the interests of” in section 19(2) broadly, holding that speech that has “a tendency” to cause public disorder may be restricted even if there is no real risk of it doing so.[24] As the court explained:

If, therefore, certain activities have a tendency to cause public disorder, a law penalising such activities as an offence cannot but be held to be a law imposing reasonable restriction ‘in the interests of public order’ although in some cases those activities may not actually lead to a breach of public order.[25]

The court has further clarified, however, that:

The anticipated danger should not be remote, conjectural or far-fetched. It should have proximate and direct nexus with the expression. The expression of thought should be intrinsically dangerous to the public interest. In other words, the expression should be inseparably locked up with the action contemplated like the equivalent of a “spark in a powder keg.”[26]

Where certain groups in Tamil Nadu state threatened violence if a film was allowed to be shown as the film hurt their sentiments, the Supreme Court famously held that freedom of expression cannot be suppressed on the basis of threats of violence, as “that would tantamount to negation of the rule of law and a surrender to blackmail and intimidation.”[27] It added:

What good is the protection of freedom of expression if the State does not take care to protect it? …The State cannot plead its inability to handle the hostile audience problem. It is its obligatory duty to prevent it and protect the freedom of expression.”[28]

However, in 2007, the Supreme Court upheld the Karnataka state’s ban of the award-winning Kannada novel Dharmakaarana, which was demanded by people who said the novel was inflammatory and hurt and insulted their sentiments. The court said freedom of speech and expression “must be available to all and no person has a right to impinge on the feelings of others on the premise that his right to freedom of speech remains unrestricted and unfettered. It cannot be ignored that India is country with vast disparities in language, culture, and religion and unwarranted and malicious criticism or interference in the faith of others cannot be accepted.”[29]

While the protection of “decency and morality” is a permissible basis for restriction of speech under the Indian constitution, the court has stated:

We must lay stress on the need to tolerate unpopular views in the socio-cultural space. The framers of our Constitution recognised the importance of safeguarding this right since the free flow of opinions and ideas is essential to sustain the collective life of the citizenry. While an informed citizenry is a pre-condition for meaningful governance in the political sense, we must also promote a culture of open dialogue when it comes to societal attitudes.[30]

The court found, however, that a greater degree of caution must be applied when dealing with “historically respected personalities” such as Mahatma Gandhi. [31]

One significant question on which the court has issued conflicting opinions is the one this section opens with: whether the effect of the words should be judged from the perspective of a “reasonable, strong-minded, firm, and courageous” individual, or from the perspective of whoever happens to feel aggrieved by a particular idea or viewpoint. The question is particularly acute when it comes to cases involving purported threats to public order. According to lawyer Gautam Bhatia, two main questions remain in such cases:

To what extent are the courts willing to treat citizens as autonomous, morally responsible agents, who can be trusted to listen to whatever speech or expression that they wish to, and trusted to make up their own minds about the content of what they hear? And to what extent are the courts willing to close of channels of communication because of the harm that it fears individuals might cause if they are allowed to hear, unrestricted, any speech that comes their way.[32]

II. Laws Criminalizing Peaceful Expression and Illustrative Cases

The Indian authorities are using a range of broad and vaguely worded laws to investigate, arrest, and prosecute individuals for peaceful expression. This report assesses those laws against international standards governing the protection of freedom of expression, identifying critical shortcomings and looking at how such laws too often are being used, in practice, to criminalize the peaceful exercise of that right. While some of the cases have been dismissed by courts as unfounded in the end, the existence of such vague and overly broad laws continues to have a far-reaching chilling effect on those holding minority views or expressing criticism of the government.

The Sedition Law

The sedition law, section 124A of the Indian Penal Code (IPC), was introduced by the British in 1870. The British used the law as a tool of repression to maintain colonial control, including against Indian freedom fighters such as Bal Gangadhar Tilak, who was charged with sedition twice,[33] and Mahatma Gandhi, who was jailed for six years on sedition charges.[34]

India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, criticized the law during a parliamentary debate on free speech in 1951, in which he said: “Now so far as I am concerned that particular section is highly objectionable and obnoxious and it should have no place both for practical and historical reasons, if you like, in any body of laws that we might pass. The sooner we get rid of it the better.”[35]

Yet 65 years later, the law remains on the books. Many dissenters, human rights activists, and those critical of the government have been charged under it, including in recent years.[36]

Although convictions for sedition are rare, a significant number of people continue to be charged with sedition and that number may actually be increasing. According to the government’s National Crime Records Bureau, which started collecting specific information on sedition in 2014, 47 cases were registered across the country, 58 people were arrested, and one person was convicted that year.[37] Although 2015 data is not yet available, ,media watchdog website The Hoot reported that 11 cases were booked against 19 people, in the first three months of 2016, compared to none during the same period in the previous two years.[38]

Sedition laws have generally been interpreted in the Commonwealth to require “an intentionto incite the people to violence against constituted authority or to create a public disturbance or disorder against such authority.”[39] Section 124A, however, is not so limited, providing that:

Whoever by words, either spoken or written, or by signs, or by visible representation, or otherwise, brings or attempts to bring into hatred or contempt, or excites or attempts to excite disaffection towards the Government established by law in India shall be punished with imprisonment for life, to which fine may be added, or with imprisonment which may extend to three years, to which fine may be added, or with fine.[40]

On its face, there is no requirement that the speech in question is likely to, or even intended to, incite violence or public disorder against the government. Rather, speech that is intended only to excite “disaffection against” the government may lead to criminal charges.[41] In 1962, however, the Indian Supreme Court recognized that:

If we were to hold that even without any tendency to disorder or intention to create disturbance of law and order, by the use of words written or spoken which merely create disaffection or feelings of enmity against the Government, the offence of sedition is complete, then such an interpretation of the sections would make them unconstitutional in view of Article 19(1)(a) read with clause (2).[42]

The court thus held that the statute must be construed to apply only to “acts involving intention or tendency to create disorder, or disturbance of law and order, or incitement to violence.”[43] The court stated:

[C]riticism of public measures or comment on Government action, however strongly worded, would be within reasonable limits and would be consistent with the fundamental right of freedom of speech and expression. It is only when the words, written or spoken, etc., which have the pernicious tendency or intention of creating public disorder or disturbance of law and order that the law steps in to prevent such activities in the interest of public order.[44]

While the decision helps to narrow the breadth of the law, by permitting restrictions only on speech that has a “tendency” to create public disorder regardless of the speaker’s intention, it still gives local authorities too much room for abusive application[45] and fails to provide sufficient guidance to citizens to enable them to know what is and is not a crime.[46] The authorities can claim that almost any speech critical of government actions or policies has a “tendency” to create public disorder because it arouses dissatisfaction among the populace and use the law to silence critics and stifle dissent.

An examination of recent cases makes clear that section 124A continues to be used against peaceful critics of the government and those who are viewed as somehow showing disrespect for India or its national symbols.

In December 2015, M.P. Shashi Tharoor introduced a private member’s bill in the parliament to amend section 124A to ensure that the law complies with Supreme Court guidance on what constitutes sedition and “to prevent the possibility of undue harassment of citizens who simply disagree with the Government.” The bill, as drafted, says sedition would only apply when speech “directly results in incitement of violence and commission of an offence punishable with imprisonment for life.”[47]

Students at Jawaharlal Nehru University

Kanhaiya Kumar, a student union leader at the Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), was arrested on February 12, 2016, by Delhi police after members of the student wing of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party accused him of making anti-national speeches during a meeting organized on campus. The public meeting was held on February 9 to protest the 2013 hanging of MohammadAfzal Guru, who was executed for his role in a deadly December 2001 attack on parliament.

Afzal Guru had been convicted of providing logistical support to those involved in the 2012 attack, in which five heavily-armed gunmen entered the parliament complex and opened fire indiscriminately, killing nine, including six security personnel, two parliament guards, and a gardener. All five attackers, later identified as Pakistani nationals, were killed.Afzal Guru’s conviction, in which the Supreme Court upheld his death sentence, and his secret execution by the government continue to fuel much debate in India.[48] Many Indian activists and lawyers claim that Azfal Guru did not receive proper legal representation. He did not have a lawyer from the time of his arrest until he confessed in police custody. Azfal Guru himself claimed that he had been tortured into making his confession, which he later retracted. Several Indian activists and senior lawyers have said that he did not have effective assistance of counsel.[49]

At the JNU campus meeting on February 9, Kumar allegedly had celebrated Afzal Guru as a martyr and spoke of “freedom from India,” allegations that were proven false when media outlets published the video and full text of Kumar’s speech, which contained no such remarks.[50] The evidentiary value of other video footage seeming to show Kumar shouting anti-India slogans, which was broadcast by various television news channels, was undercut when a forensic examination revealed that some of the video clips had been doctored.[51] While some anti-India slogans had been voiced at the event, witnesses say it is unclear whether they were made by students or by outsiders trying to cause trouble.[52] After the Delhi police admitted in court that Kumar had “not been seen” voicing anti-national slogans in the video footage available, the Delhi High Court granted him interim bail for six months on March 2.

Two other JNU students, Umar Khalid and Anirban Bhattacharya, were also arrested for sedition for the same incident. The two surrendered to the police on February 24 and were granted bail on March 18. Police had booked three other students, Ashutosh Kumar, Anant Prakash, and Rama Naga, for sedition in relation to the same incident. In April, following the recommendations of an internal inquiry committee, the university administration punished several students for their role in the February 9 meeting on campus. Penalties ranged from suspension to fines to leaving the hostel; Umar Khalid and Anirban Bhattacharya were suspended, and fines were imposed on Kanhaiya Kumar and Rama Naga. Khalid and Bhattacharya have filed pleas in the Delhi High Court to challenge their suspensions and over a dozen students were on an indefinite hunger strike to protest the administration’s decision at the time of writing.[53]

Kanhaiya Kumar and his supporters were also attacked on two separate occasions by men wearing lawyers’ black coats when Kumar was produced in court for bail hearings. Among those caught on camera apparently assaulting Kumar’s supporters during the first attack on February 15 was a member of the Delhi state legislature from the Bharatiya Janata Party, Om Prakash Sharma.

The second attack on Kumar occurred on February 17 despite the Supreme Court’s having decided to restrict the number of people inside the courtroom for Kumar’s hearing and having asked the police chief to ensure his safety. On the second occasion, Kumar was slapped, kicked, and punched by men appearing to be lawyers as he was being escorted inside the courtroom, according tomedia reports.[54] Several journalists also said they were threatened and attacked.[55] The Supreme Court rushed a delegation of senior lawyers to assess the situation, which confirmed that Kumar was assaulted and that the police had failed to ensure his safety.[56]

S.A.R. Geelani

Former Delhi University professor S.A.R. Geelani was arrested by Delhi police on February 16, 2016, for allegedly having organized a February 10 event at the Press Club in Delhi, also to protest the 2013 hanging of Afzal Guru.

The police claim that anti-national slogans were made at the event, including calls for the independence of Kashmir state. The police said they filed a complaint taking cognizance of the offence on their own, based on news coverage of the event.

Geelani was arrested mainly because, according to the police, he organized the event. “The request for booking a hall for the event at the Press Club was done through Mr Geelani's e-mail and it was proposed to be a public meeting, which did not turn out to be so,” a police officer told media.[57] Geelani is the vice-president of the Committee for the Release of Political Prisoners, which reportedly organized the meeting.[58] In opposing Geelani’s bail, the public prosecutor argued in court that Geelani put up a poster glorifying Afzal Guru.[59] A Muslim from Kashmir, Geelani had been Afzal Guru’s co-accused in the 2001 parliament attack case and himself had initially been sentenced to death by a lower court before the Delhi High Court acquitted him of all charges in 2003, a decision later upheld by the Supreme Court.[60] After his acquittal, Geelani had campaigned against the death penalty imposed on Afzal Guru and has long called for self-determination for Kashmir. His supporters say he is being targeted because of this history.

Geelani received bail on the sedition charges on March 19.[61]

S. Kovan

On October 30, 2015, police in Tamil Nadu state arrested 52-year-old folk singer S. Kovan under the sedition law for two songs that criticized the state government for allegedly profiting from state-run liquor shops at the expense of the poor.[62] Kovan, a resident of Tiruchirappalli district, was also booked under Indian Penal Code section 153 for provocation with intent to cause riot and sections 505(1), (b), and (c) for making statements that could cause public mischief.[63]

Kovan is a member of the Makkal Kalai Ilakkiya Kazhagam, or People’s Art and Literary Association, which has long used art, music, and theater to educate members of marginalized communities and raise issues such as corruption, women’s rights, and discrimination against Dalits (formerly known as “untouchables”). In the controversial songs, he blamed the government for choosing revenue from liquor sales over people’s welfare.[64]

Kovan’s family alleges that plainclothes police officers, who refused to show identification, came in the middle of the night to arrest Kovan. Kovan’s lawyer told Human Rights Watch that the police officers violated legal procedures, refusing to tell the family where they were taking him.[65] To find out about Kovan’s whereabouts, his lawyer filed a habeas corpus petition in the Madras High Court, after which the court told the police to follow legal guidelines. Kovan was then produced before a magistrate on October 31 as per procedure and was remanded in judicial custody for 15 days. The police also reportedly tried to arrest the owner of the website,vinavu.com, on which the songs were first uploaded.

Meanwhile, on November 6, the chief metropolitan magistrate in Chennai ordered Kovan to be remanded in police custody for two days. The police said they needed to interrogate Kovan, claiming that he “habitually indulged in offences against the state” and that he and the People’s Art and Literary Association allegedly had links with Naxal groups, which were outlawed. Kovan appealed and the Madras High Court sent Kovan back to judicial custody, saying the state had failed to produce any evidence to prove the allegations regarding Naxal links. On November 30, the Supreme Court dismissed the Tamil Nadu government’s plea challenging the High Court order.[66] Kovan was released on bail on November 16.

On March 26, 2016, the police in Trichy bookedsix other activists under the sedition law for criticizing the state’s policy of earning revenue through sale of liquor, controlled by the state-owned Tamil Nadu State Marketing Corporation (TASMAC), and for calling for prohibition. The accused were booked a month after they had organized and addressed a public meeting on February 14 in which Kovan also participated. The six are Anandiammal and David Raj; C Raju and Kaliyappan of Makkal Adhigaaram or People’s Power group; Vanchinathan, coordinator of the Manitha Urimai Pathukappu Maiyam or People’s Right Protection Centre; and Dhanasekharan, general secretary of the TASMAC Employees Union. The police have also accused them of causing intentional insult with intent to provoke breach of peace, and making statements amounting to public mischief with intent to cause, or which is likely to cause, fear or alarm to the public.[67]

Students in Kerala

In August 2014, authorities in Kerala charged seven youth, including students, with sedition because they refused to stand up during the national anthem at a state-owned movie theater in Thiruvananthapuram. According to one of the accused, Salman M., he and his friends Shiyas S., Rajesh Paul, Harihara Sharma, Deepak A. G., Thampatty Madhusood, and Sini S. S. were verbally abused by other movie-goers when they did not stand up for the national anthem. The police charged all seven with sedition based on a complaint by one of those other movie-goers.

Salman, who was 25 years old and a student at the time, was arrested at his home on August 19. He also faces charges under the Prevention of Insults to National Honour Act and section 66A of the Information Technology Act (though the provision was struck down by the Supreme Court in March 2015) for comments he made on Facebook on August 15, India’s Independence Day. The other six received anticipatory bail.

Salman told Human Rights Watch he was targeted by the police because he is a Muslim and was a regular participant in demonstrations against the state, including protests against counterterrorism laws and against a civil nuclear power plant at Kudankulam. “During interrogation, the special branch police told me that they had already been keeping an eye on me because of my Facebook status on Independence Day,” he said.[68]

Salman was finally granted bail by the Kerala High Court on September 22, after being denied bail by lower courts.[69] At the time of writing, the police had not filed a charge sheet in the case. Meanwhile, Salman had to submit his passport to the court and visit the police station twice a week for six months as conditions of his bail.

Students from Jammu and Kashmir

In March 2014, authorities in Uttar Pradesh charged over 60 Kashmiri students with sedition for cheering for Pakistan in a cricket match against India. While the First Information Report did not name any students, the students were also booked under section 153 of the Indian Penal Code, which deals with spreading hatred between castes and communities, and under section 427 for causing damage to property. The students from Kashmir, studying at a private university in Meerut city, were watching the match with other students in the university hostel. The Kashmiri students alleged they were attacked by other students after the match ended with Pakistan beating India.

Kashmiri student Ghulzar Ahmad told Reuters: “As soon as the match ended, the Indian students chased us. We hid in our rooms. They abused us and threw stones at our rooms and broke our laptops. They said Kashmiris and Pakistanis should leave.”[70] The university management ordered an inquiry and temporarily suspended all Kashmiri students residing in the hostel as a “precautionary measure.”[71] “The college never heard our side of the story. Some us were crying as we had no money,” one of the students who had returned to his home in Kashmir told a reporter.[72] Three days later, the university decided to revoke the suspension.[73]

The sedition charges prompted condemnation from civil society as well as from both the chief minister and opposition party leaders in Jammu and Kashmir state.[74] The Uttar Pradesh state government dropped the sedition charge after seeking a legal opinion from the law ministry.

Aseem Trivedi

On September 8, 2012, political cartoonist Aseem Trivedi was arrested after a member of a political party complained that his cartoons mocked the Indian parliament and the national emblem.[75] He was charged with sedition and with violating section 2 of the Prevention of Insults to National Honour Act, 1971, which criminalizes insults to the national flag and the constitution, and section 66A of the Information Technology Act, which criminalizes posting “information that is grossly offensive or has menacing character.” The authorities had previously suspended his website, Cartoons Against Corruption, after a complaint by a local politician alleging that it showcased inappropriate content.[76]

Trivedi’s arrest prompted widespread condemnation among civil society and in media. Three days after he was arrested, on September 11, 2012, the Bombay High Court granted him bail. On September 14, while hearing a petition filed by a lawyer claiming Trivedi’s arrest was illegal, the High Court slammed the Mumbai police for arresting Trivedi on “frivolous” grounds and called it a breach of his freedom of expression. The court also observed that parameters for application of the sedition law must be established or “there will be serious encroachment of a person’s liberties guaranteed to him in a civil society.” Reprimanding both the state government and the police, the judges asked:

What is the government’s stand now? Does it intend to drop the charge? Someone has to take political responsibility for this. Why did the police not apply its mind before arresting him on sedition charges?[77]

In October 2012, police dropped the sedition charges against Trivedi after a legal opinion of the state advocate general.[78] Although the Supreme Court struck down section 66A of the Information Technology Act in March 2015, Trivedi still faces charges under the Prevention of Insults to National Honour Act. In its March 2015 ruling that Trivedi should not have been charged with sedition, the Bombay High Court reiterated that every citizen has the right to criticize the government and its policies and that there must be actual incitement of violence for sedition charges to stand.[79]

In its ruling, the court also accepted a set of proposed guidelines for police that had been submitted by the Maharashtra government. The government said it would issue a circular to the police clarifying that sedition charges should be brought only for incitement of violence or acts that have the intention or tendency to create public disorder. The guidelines also stipulate that the police obtain a legal opinion in writing, along with reasons, from the law officer of the district and from the state’s public prosecutor before filing sedition charges.[80]

In August 2015, the state government issued new guidelines to the police. However, the government circular, apparently in a mistranslation from English to the Marathi language, was missing the crucial caveat regarding incitement of violence, permitting police to charge individuals with sedition for merely criticizing the government.[81] The government was forced to withdraw the guidelines in October, following protests by civil society organizations and a high court order directing it to withdraw the circular or issue a new one.[82]

Protesters at Kudankulam Nuclear Plant

In 2012, local authorities in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu filed sedition complaints against thousands of protesters campaigning against the construction of a nuclear power plant.[83] Those protesting the Kudankulam nuclear plant included ordinary villagers, many belonging to fishing communities, who were concerned about the plant’s potential adverse effects on their health and livelihoods. Many had experienced the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami firsthand and worried about a possible catastrophe like the meltdown which occurred at the Fukushima nuclear plant in Japan after a 2011 tsunami.

Instead of allaying their concerns, authorities in Tamil Nadu filed criminal cases against thousands of people on charges including sedition, waging or abetting war against the state, disrupting harmony, and unlawful assembly.[84] S.P. Udaykumar, founder of the People’s Movement Against Nuclear Energy (PMANE), told Human Rights Watch that as of 2013, 8,956 individuals had been booked for sedition.[85]

According to Usha Ramanathan, a legal scholar, the state’s motive in charging protesters with provisions such as sedition is to silence dissent.

They know even if all the cases fall at the end of the day it doesn’t matter, because they’ve had their purpose served. You can beat people up, you can put them away. It’s a total abuse of a power that actually doesn’t exist, but which they have managed to cultivate for themselves.[86]

A report on a public hearing organized by activists in the Chennai Solidarity Group in May 2012—participants in the hearing committee included A. P. Shah, former chief justice of the Madras and Delhi High Courts—found that the state government had denied both freedom of speech and freedom of assembly to the villagers. It also found that the state had denied other rights to the villagers such as freedom of movement, and the rights to food, education, livelihood, and access to health services.[87]

Another report, in September 2012, by an independent fact-finding team made up of former judge of the Bombay High Court B. G. Kolse Patil, journalist Kalpana Sharma, and writer R. N. Joe D’Cruz, alleged that police used “unjustified” force against peaceful protesters. According to the report, the police hit protesters with lathis (batons) and shot tear gas shells into the crowd to disburse it and as a result, several men and women suffered injuries and burn marks. The report noted:

If people who have resisted and protested peacefully for a year can be charged with sedition and waging war against the nation in such a cavalier way as has been done here, what is the future of free speech and protest in India?[88]

Arundhati Roy and Ali Shah Geelani

In 2010, author and activist Arundhati Roy and Kashmiri separatist leader Syed Ali Shah Geelani were threatened with sedition charges for publicly speaking in favor of Kashmiri secession. In New Delhi, a magistrate directed the police to investigate allegations of sedition against them based on private complaints, rejecting the police status report which stated that “essential ingredients” for a sedition case were missing since there was no evidence of inciting violence.[89] The police proceeded with the investigation but there have been no further developments in the case.[90] When informed of a possible sedition case against her, Roy said:

Pity the nation that has to silence its writers for speaking their minds. Pity the nation that needs to jail those who ask for justice, while communal killers, mass murderers, corporate scamsters, looters, rapists, and those who prey on the poorest of the poor, roam free.[91]

Binayak Sen

On December 24, 2010, a court sentenced Dr. Binayak Sen, a vocal critic of the Chhattisgarh state government's counterinsurgency policies against violent Maoist rebels, to life in prison for sedition.[92] Sen, a medical doctor and activist with the People’s Union for Civil Liberties in Chhattisgarh state, was detained on May 14, 2007, under the Chhattisgarh Special Public Security Act. Sen was eventually charged with sedition, anti-national activities, treason, criminal conspiracy, and waging war against the state, among other crimes.

Sen was among the most vocal critics of the government-backed vigilante group Salwa Judum, which attacked, killed, and forcibly displaced tens of thousands of people in armed operations against Maoist rebels after its creation in 2005. Sudha Bharadwaj, a lawyer and activist with People’s Union for Civil Liberties in Chhattisgarh, argued that the government wanted to use Sen’s example to deter others from speaking out against Salwa Judum abuses.

This is actually, I would say, a very politically motivated case, because he was—as the general secretary of Chhattisgarh PUCL, he did expose and he actually was instrumental in getting together a team of human rights activists, who for the first time investigated a phenomenon called Salwa Judum, which was claimed to be a spontaneous peaceful movement against Naxalites in the Bastar region, but they found that it was not so. It was very much a state-sponsored campaign… He was a thorn in the side of the government, and they just wanted to not only end—they wanted to send a message, you know, to silence dissent, to silence this kind of activity.[93]

Sen’s imprisonment, trial, and the Supreme Court judgment which granted him bail pending appeal all highlight how the process can be the punishment in these cases.

Sen’s application for bail was rejected by the Chhattisgarh High Court. He then spent two years in jail before the Supreme Court granted him bail. A year later, on December 24, 2010, a court in Raipur convicted him of sedition and sentenced him to life imprisonment, despite finding no evidence that he was a member of any outlawed Maoist group or that he was involved in violence against the state. Immediately after the verdict, Sen’s bail was revoked and he was arrested again.[94]

Sen’s application for bail pending the hearing of his appeal was rejected by the Chhattisgarh High Court and he remained in jail until April 2011, when the Supreme Court again granted him bail. Supreme Court Justices H.S. Bedi and C.K. Prasad said:

We are a democratic country. He may be a sympathizer. That does not make him guilty of sedition… No case of sedition is made out on the basis of materials in possession unless you show that he was actively helping or harboring them [Maoists].[95]

Sen’s appeal is still pending. Had he not been granted bail, he would now have spent nine years in jail. As lawyer Vijay Hiremath noted,

For anyone to go to jail, it’s traumatic. It can break you mentally and if one spends too much time in jail, it can really harm them mentally, physically, and emotionally. In the case of Binayak Sen, he was unwell for a long time because of the time he spent in jail.[96]

The above cases are but a few examples of the way in which the sedition law continues to be used by state and local authorities to harass writers, journalists, students, human rights activists, and those critical of the government.

A 2011 report by the Alternative Law Forum and the Centre for the Study of Social Exclusion and Inclusive Policy at the National Law School of India University, Bangalore, looked at a number of cases brought pursuant to section 124A. It found a divide between higher and lower courts in how the law was applied, and identified several cases in which the High Court granted bail or acquitted the accused of sedition charges.[97]

Charges under the sedition provision raise particular concerns because the speech at issue usually involves discussion of the government or judicial policy or actions.[98] A critical aspect of the right to freedom of expression is the right of individuals to criticize or openly and publicly evaluate their governments without fear of interference or punishment.[99]

As the New Zealand Law Commission stated in recommending the abolition of New Zealand’s sedition laws:

The heart of the case against sedition lies in the protection of freedom of expression, particularly of political expression, and its place in our democracy. People may hold and express strong dissenting views. These may be both unpopular and unreasonable. But such expressions should not be branded as criminal simply because they involve dissent and political opposition to the government and authority.[100]

New Zealand and the United Kingdom are among the countries that have abolished their sedition laws in recent years.[101] India should follow their lead.[102]

Criminal Defamation

In India, defamation is both a civil and criminal offense. Section 499 of the Indian Penal Code sets out the definition of defamation,[103] and section 500 provides for up to two years in prison and a fine. Criminal defamation is not used as often as civil defamation, nor does it generally result in convictions, but, as with the sedition provision, the threat of criminal action has a chilling effect on free speech.

Criminal defamation is a bailable, non-cognizable, and compoundable offence in India. This means that the police require the permission of the court to register or investigate a case. The accused cannot be arrested without a warrant. The Code of Criminal Procedure states that the complaint has to be made by the “person aggrieved.”[104] The charges can be dropped if the complainant and the accused enter into a compromise, even without the permission of the court.

Criminal defamation, by virtue of the disproportionate penalty it imposes on speech, chills freedom of expression as guaranteed under international law. The UN special rapporteur on freedom of expression has recommended that criminal defamation laws be abolished,[105] as have the special mandates of the United Nations, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, and the Organization for American States, which have stated that “criminal defamation is not a justifiable restriction on freedom of expression; all criminal defamation laws should be abolished and replaced, where necessary, with appropriate civil defamation laws.”[106] The United Kingdom and New Zealand, among other countries, have already done so.[107]

As then-Special Rapporteur on freedom of expression Frank La Rue noted in 2012:

The problem with defamation cases is that they frequently mask the determination of political and economic powers to retaliate against criticisms of mismanagement or corruption, and to exert undue pressure on media.[108]

Criminal defamation cases involving government officials or public persons are particularly problematic. While government officials and those involved in public affairs are entitled to protection of their reputation, including protection against defamation, as individuals who have sought to play a role in public affairs they should tolerate a greater degree of scrutiny and criticism than ordinary citizens. This distinction serves the public interest by making it harder for those in positions of power to use the law to deter or penalize those who seek to expose official wrongdoing, and it facilitates public debate about issues of governance and common concern.[109]

Human Rights Watch believes that criminal defamation laws should be abolished, as criminal penalties are always disproportionate punishments for reputational harm and so unacceptably burden peaceful expression. Criminal defamation laws are open to easy abuse, resulting in very harsh consequences, including imprisonment. As repeal of criminal defamation laws in an increasing number of countries shows, such laws are not necessary for the purpose of protecting reputations.

While defamation should be handled as a civil matter, “civil penalties for defamation should not be so heavy as to block freedom of expression and should be designed to restore the reputation harmed, not to compensate the plaintiff or to punish the defendant,” recommended the UN special rapporteur on the right to freedom of expression. In particular, “pecuniary awards should be strictly proportionate to the actual harm caused, and the law should give preference to the use of non-pecuniary remedies, including, for example, apology, rectification and clarification.”[110]

In recent years, criminal and civil defamation laws have increasingly been used by corporations and business houses to harass journalists and bloggers and to suppress critical speech.[111]

Subramanian Swamy v. Union of India

In late 2014, Subramanian Swamy of the Bharatiya Janata Party filed a petition with the Indian Supreme Court challenging the constitutionality of criminal defamation laws for violating the right to freedom of speech and expression. Swamy faces defamation charges for allegedly making comments against Tamil Nadu’s chief minister on Twitter. The comments discuss allegations of corruption, among other things.[112]

In addition to Swamy’s petition, 24 other petitions were filed seeking the striking down of criminal defamation provisions, including those of Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal and Congress Vice President Rahul Gandhi. The Court began hearing the cases as a group in July 2015.[113]

The central government argued for the retention of the criminal defamation provision, saying it had stood the test of time and that monetary compensation through civil lawsuits is not a sufficient remedy for damage to a person’s reputation. “A person’s reputation is an inseparable element of an individual’s personality and it cannot be allowed to be tarnished in the name of right to freedom of speech and expression because right to free speech does not mean right to offend,”the attorney general said in his submission to the Supreme Court.[114]

The petitioners argued that the threat of criminal prosecution leads to self-censorship, chilling the exercise of the right to free expression. They also emphasized that the arduous process of a criminal trial and its disproportionate impact in comparison with that of a civil suit— the “process as punishment” point made above—causes undue harassment and fear, and stifles free speech.[115]

In May 2016, however, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the law saying:

Rightto free speech cannot mean that a citizen can defame theother. Protection of reputation is a fundamental right. It isalso a human right. Cumulatively it serves the social interest.[116]