Liz Luras enlisted in the US Army because she came from a patriotic family – her father served in Vietnam and her grandfather fought in World War II – and to help pay for college. Her family, who lived in Oregon, couldn’t afford a car. To pay for her ballet classes, Liz and her mom cleaned the ballet studio and sewed costumes.

“[Enlisting] seemed like the perfect solution,” she said. “To serve my country and make sure I had a way to pay for my education.”

She scored high on the aptitude tests and was selected for intelligence communications, such as copying code, and given top-secret clearance. She went through a rigorous background check for the clearance that included any criminal history as well as mental and physical health screenings.

She graduated from high school on a Friday and shipped out that weekend – she didn’t even attend her graduation.

Liz excelled in boot camp and training. Her superiors encouraged her military career and said they would nominate her for the military academy at West Point. Her future seemed assured. “It was the most exciting time,” she said. “I felt so empowered as a patriot, soldier and woman. I could run, huck a rucksack, shoot an M16, and I loved it.”

Then everything changed. Her date to the Marine Corps ball raped her, and her “battle buddy,” a partner assigned by the military, reported the assault to superiors.

The rape set off a series of events – including physical hazing, sexual harassment and two more rapes – that led ultimately to Liz being forced out of the military career she loved. Despite being honorably discharged, she was unfairly labeled as having a “Personality Disorder” or PD in her discharge papers – although she was never diagnosed by a doctor and showed no signs of PD in her pre-army screening. Because of this black mark on her record, when she applied for law enforcement or government jobs – where veterans are often given preference – she didn’t even get interviews.

Only later did she learn that PD discharges, a term used to describe a mental health condition that can disqualify someone from military service, were once considered the easiest way to get rid of someone in the military and to silence them.

Based on more than 270 interviews, documents from US government agencies in response to public record requests, and data analysis, a new Human Rights Watch report illuminates the impact of “bad discharges” on military personnel who left or were forced out of the military after reporting a sexual assault. In response to public pressure the military has taken some steps in recent years to improve how it handles sexual assault cases. But almost nothing has been done to reverse the harm to veterans who reported sexual assault in the past. Like Liz, many lost much more than their military careers, and have no effective recourse to correct their records.

After Liz’s battle buddy reported her rape, Liz was taken to a hospital. She was interviewed by both military and civilian police, as well as her military command. Her rapist was questioned but never charged by either the civilian police or the military.

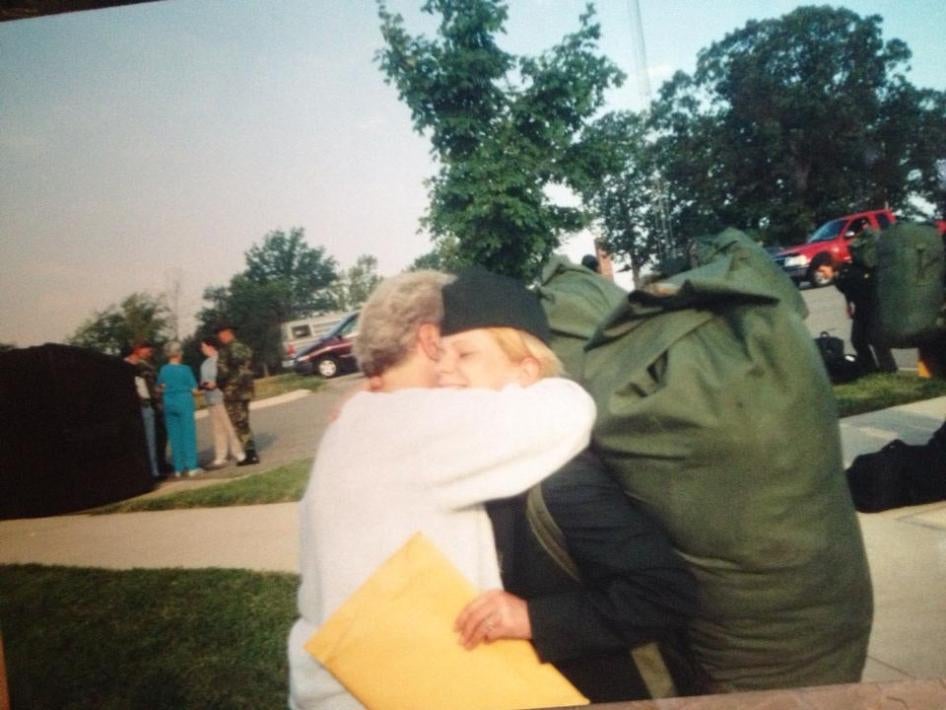

Liz was sent home on emergency leave – the American Red Cross gave her a plane ticket, but the cost was later deducted from her pay. When she returned, the harassment began.

She received multiple disciplinary notices (“article 15s”), including for “failure to soldierize” – specifically, for having a pale pink, not peach, manicure, or for having boxers over her military underwear, or for wearing lip gloss. Before reporting the rape, the same lip gloss and nail polish hadn’t been an issue. She fought these charges, and many were dropped.

At night, a drill sergeant would come into her room while she was sleeping and stand over her bed to intimidate her. He made comments about her breasts.

Liz told her father about the harassment. He called their congressman, who contacted Liz’s supervisor. The supervisor called Liz into his office and ordered her to tell the congressman nothing was wrong. Half a dozen drill sergeants and the command sergeant major stood in a semi-circle around her as she told the congressman over the phone that everything was fine.

It got worse from there. It was clear her command wanted her out of the military, Liz said. West Point was taken off the table. She was confronted in the bathroom and threatened by female friends of the soldier who raped her. She was taken out of her room in the middle of the night repeatedly for “extra duty” – to clean toilets, repaint a hallway she had recently painted, or do pushups or sit-ups until she vomited, well past the point of exhaustion. All of this, she believes, in retaliation for speaking out.

She was raped twice more, she believes in retaliation for reporting the first rape. She didn’t report either rape. “The retaliation was so terrible,” she said. “I was more afraid of the retaliation than of being raped.”

Despite all these horrors, she still wanted a military career. She took seriously her oath to serve, she said.

In a moment of utter desperation, she agreed to marry someone she barely knew for the chance to move out of the barracks and be out of reach of those hazing her at night.

Then her superiors forbade her from moving out of the barracks.

One Friday, her drill sergeant took her to a file cabinet room and told her she wouldn’t be reclassified to another job, a request she made to avoid her harassers, but that she would be given an honorable discharge and could later return to the military. He slammed the discharge papers on the file cabinet. “Fucking sign it, Luras,” he ordered, all the while keeping his hand pressed on the papers. She was on a flight home that afternoon.

Normally, soldiers are notified they’re to be discharged, a process that often takes six months or more and can involve military attorneys, medical evaluations, and other advisers.

Only later, when Liz looked at the paperwork, did she realize “Personality Disorder” was given as the reason for separation on her discharge papers. This despite no history of mental health problems and no diagnosis from a professional.

Liz’s unexpected ejection from the military meant she lost out on medical and other military benefits. She never saw the money earmarked for college that the military had deducted from her check for the Montgomery G.I. Bill.

Despite everything, Liz wanted to keep her military career. She enrolled at the University of Oregon and joined the Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC). Although she had a clean bill of health from the military and a straight A average, in her second semester she was pulled aside by the ROTC commander and told she had a black mark on her record and could not participate, nor could she reenlist in the Army. ROTC pays for its students’ tuition, but after ROTC told her to leave, it didn’t pay for any of the classes Liz had taken.

Her PD discharge made it more difficult to get a job. When veterans apply to law enforcement or government jobs, their resumes often get moved to the top of the pile under a points system. She applied for a sheriff position and a public affairs job, among others. But she was never called for an interview, she said, until she stopped sharing her service record.

Since her discharge, both civilian and Veterans Affairs (VA) doctors have confirmed she never had PD, although they did diagnose Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) stemming from the rapes and retaliation. However, she is afraid to go to the military’s Discharge Review Board.

Historically, the boards offer little hope for correcting records. Applicants almost never receive hearings and dozens of cases are decided in a few hours. Depending on the board, often only between 1 and 10 percent of challenged discharges are overturned.

Liz has struggled because of her military experiences, which initially left her feeling numb. She was at times homeless, after being laid off and trying unsuccessfully to find employment. She worries that potential employers may have judged her for speaking openly about her rape and PD discharge. She believes that as a result of her PD discharge, she’s adopted a form of perfectionism: “With PD vets, people tell you you’re crazy when you know you’re not, so you do everything to be perfect. You never want to give them a reason to doubt your sanity.”

Today, Liz has two steady jobs, and she recently graduated from college. As part of Service Women’s Action Network (SWAN), she’s marched on Capitol Hill, and spoke in front of Congress about rape in the military in 2012 and in 2013. But even within SWAN, she didn’t initially share that she had a PD discharge. “There’s this whole other layer of shame,” she said. It felt too complicated and overwhelming to share, especially as the issue was relatively unknown.

Liz competed in Ms. Veteran America, which raises money for homeless female veterans and their children. Although the group initially questioned Liz’s story about her PD discharge, today the organization supports female veterans who have been denied their VA benefits because of PD discharges.

For the past six years Liz has worked in suicide prevention for veterans. “I tell everyone to find what you would die for and live for it. Because one voice can make a difference and that difference begins with you.” She pauses. “That’s the whole reason why I stand up and start talking about this and don’t bury it.”

“I want Congress to wake up. And I want them to step up and start helping us. Our warriors deserve justice.”