The new, civilian-led government in Burma under Aung San Suu Kyi’s leadership could herald a new era for human rights in Burma. But before euphoria breaks out, the United Nations Human Rights Council should take into account the many challenges Burma faces.

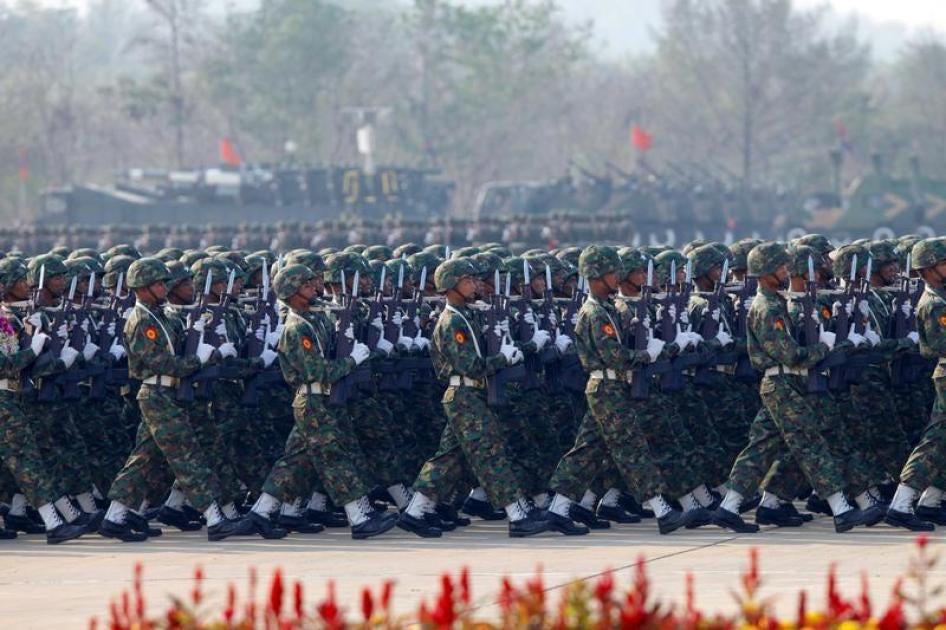

It’s hard to overstate the systemic problems facing the incoming government. Military operations in Burma’s ethnic minority areas have increased over the past year, even as a partial ceasefire with several ethnic groups has been touted – and sometimes misrepresented – as a nationwide ceasefire. Renewed fighting has displaced thousands of civilians amid allegations of serious laws-of-war violations by government forces and ethnic armed groups, including forced labor, torture and ill-treatment, and sexual violence against women.

Burma’s outgoing military-backed government has used the police and courts to imprison people on politically motivated charges, raising the number of political prisoners to approximately 100, while another 400 people face criminal charges for peaceful activism. This is the most at any time since the major political prisoner releases of 2012.

A raft of abusive laws remain on the books, whose use even the new government may not be able to stop. The military-drafted constitution allows the armed forces to appoint the home affairs minister – who controls the police -- as well as the defense and border affairs ministers. An unreformed judiciary remains corrupt, incompetent, and subordinate to the military. The military remains above civilian control, with complete impunity for past and ongoing crimes.

Race and religion remain unresolved flashpoints. The Rohingya Muslim minority, long a target of government repression, were disenfranchised during recent elections. More than 130,000 remain in squalid displacement camps, while the remaining 1.1 million face everyday curbs on basic rights, including their freedom of movement. Aung San Suu Kyi has shown no inclination to stand up for them.

At HRC negotiations in Geneva this week, the European Union and other governments have seemed ready to relax international scrutiny before the new government has even taken office. Some even want to move Burma from an Item 4 situation, the agenda category for states with serious human rights issues, to Item 10, which is intended for states of lesser concern that only need technical assistance.

It is wishful thinking that a single election and the partial withdrawal of the military from governance has transformed the situation. The rights situation in Burma remains poor. Now is exactly the wrong time to relax international scrutiny. On the contrary, the HRC has an important opportunity to fully engage on rights in Burma by working with the new government to address deeply entrenched rights violations. This includes repealing rights-abusing laws; unconditionally releasing political prisoners and dropping charges against hundreds more; ending discrimination and internment of Rohingya; and producing a roadmap for constitutional reform that provides for a genuinely democratic political system under civilian rule. The HRC should call on Burma to agree to the swift creation of a Burma office of the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights with a full mandate to promote and protect rights.

Powerful forces in Burma will try to stop reforms in their tracks. The HRC and UN member states need to send a strong message that they will stand with the Burmese people until the reform process is complete.